Dejaco C, Ramiro S, Duftner C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in large vessel vasculitis in clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 May;77(5):636-643. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212649. Epub 2018 Jan 22. PubMed PMID: 29358285.

Salvarani C, Pipitone N, Versari A, Hunder GG. Clinical features of polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012 Sep;8(9):509-21. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.97. Epub 2012 Jul 24. Review. PubMed PMID: 22825731.

Dasgupta B, Borg FA, Hassan N, et al; BSR and BHPR Standards, Guidelines and Audit Working Group. BSR and BHPR guidelines for the management of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010 Aug;49(8):1594-7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq039a. Epub 2010 Apr 5. PubMed PMID: 20371504.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is an inflammation of predominantly large- and medium-sized arteries that is frequently granulomatous and develops almost exclusively after the age of 50 years. It is characterized by involvement of the arteries branching from the aortic arch. Most often branches of the external carotid artery are involved, but any of the following arteries may be affected (in order of frequency): temporal arteries, vertebral arteries, posterior ciliary arteries, ophthalmic artery, internal carotid artery, external carotid artery, and central retinal artery. The name “temporal arteritis” is misleading, as temporal arteries are not always affected in patients with GCA and may be involved in patients with other vasculitides.

In general terms, large-vessel vasculitis (LVV) occurring in patients aged >50 years is usually diagnosed as or has a clinical form of GCA or more specifically, if temporal arteries are involved, of temporal arteritis. In younger people (<50 years and more so <40 years) the clinical presentation and diagnosis is usually that of Takayasu arteritis (see Takayasu Arteritis).

Clinical FeaturesTop

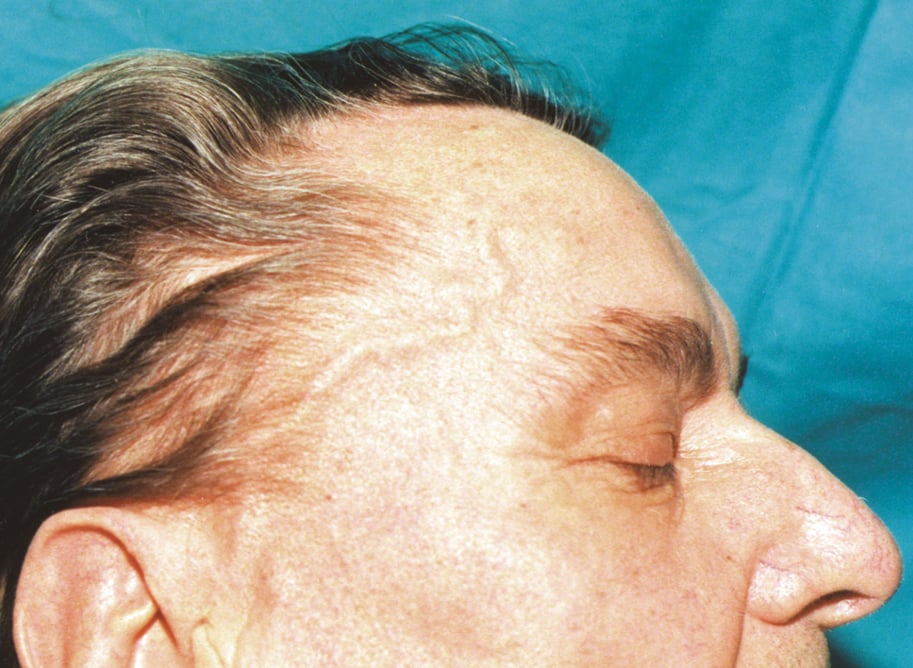

The majority of patients have general symptoms, like low-grade or high-grade fever, fatigue, anorexia, and weight loss. Two-thirds of patients have severe headache, usually bilateral temporal or generalized, that is continuous, prevents them from sleeping, and does not resolve completely after the use of analgesics. Painful swelling of the temporal artery (Figure 1) may also occur, which is clearly visible under the skin and often erythematous. In 30% of patients ocular symptoms develop, including diplopia and transient loss of vision (amaurosis fugax) progressing to a partial or total loss of vision due to the involvement of mainly ciliary arteries or the central retinal artery. Patients with the involvement of the visceral branches of the external carotid artery may have claudication and occasionally painful ulcerations of the tongue as well as claudication of the masseter muscles due to ischemia (jaw claudication). Neurologic manifestations such as transient ischemic attack or stroke, polyneuropathy, or mononeuropathy may be present. Arteritis may lead to the formation of an aneurysm and its rupture; one of the complications may be aortic dissection. Approximately 50% of patients have coexisting polymyalgia rheumatica.

Considering the risk of loss of vision, new-onset GCA should be regarded as an ophthalmologic emergency. Features indicating an increased risk of permanent loss of vision include amaurosis fugax (precedes permanent loss of vision in almost half of patients), jaw claudication, and abnormalities of a temporal artery found on physical examination.

DiagnosisTop

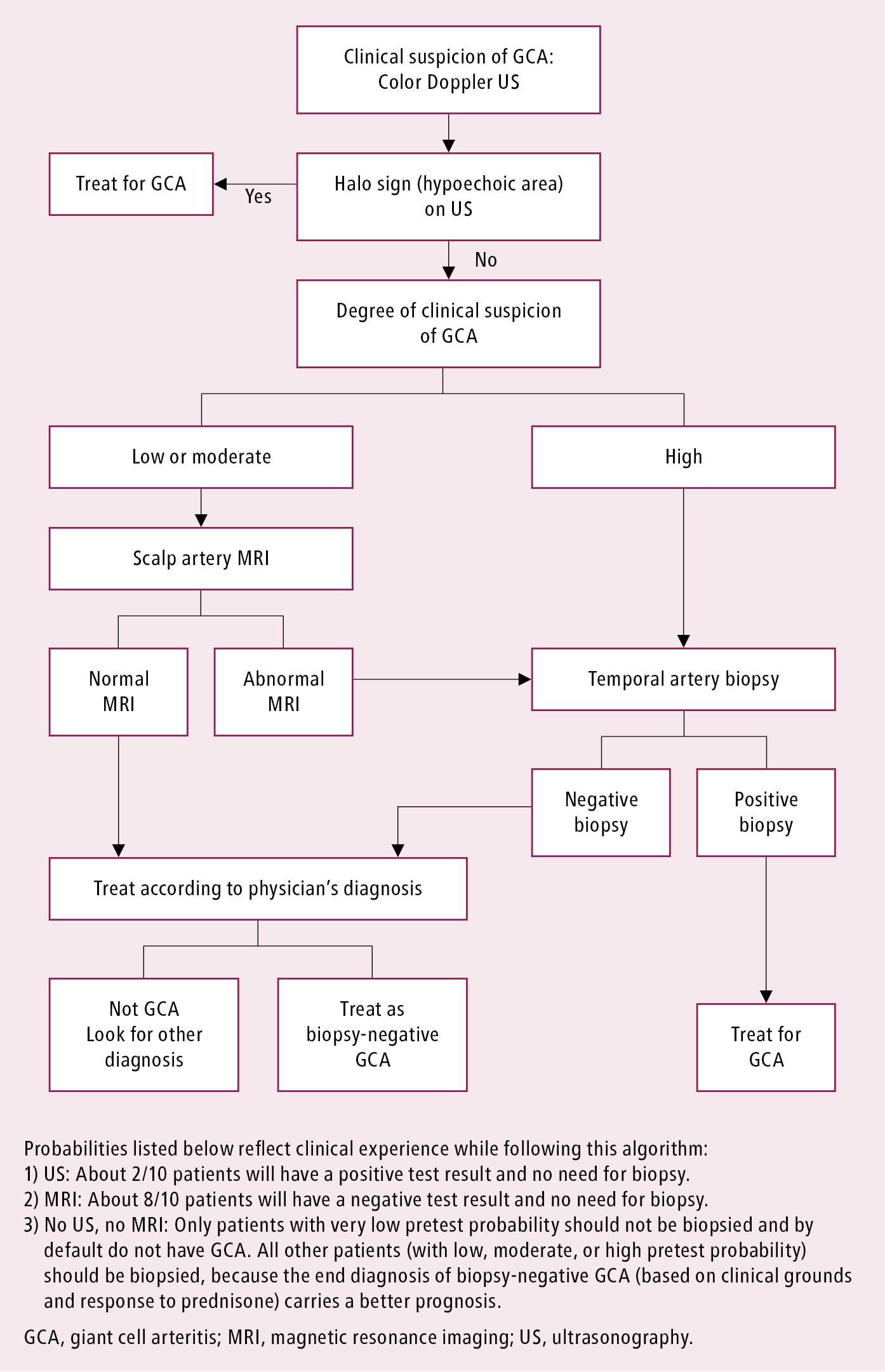

Diagnostic algorithm: Figure 2.

1. Blood tests: Increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (usually >100 mm after 1 hour, but ESR within the reference range does not exclude the diagnosis of GCA, as <5% of patients have a normal ESR); elevated serum levels of acute phase proteins (C-reactive protein [CRP], fibrinogen); anemia of chronic disease; reactive thrombocytosis; a minor increase in liver function tests, particularly alkaline phosphatase (in ~30% of patients).

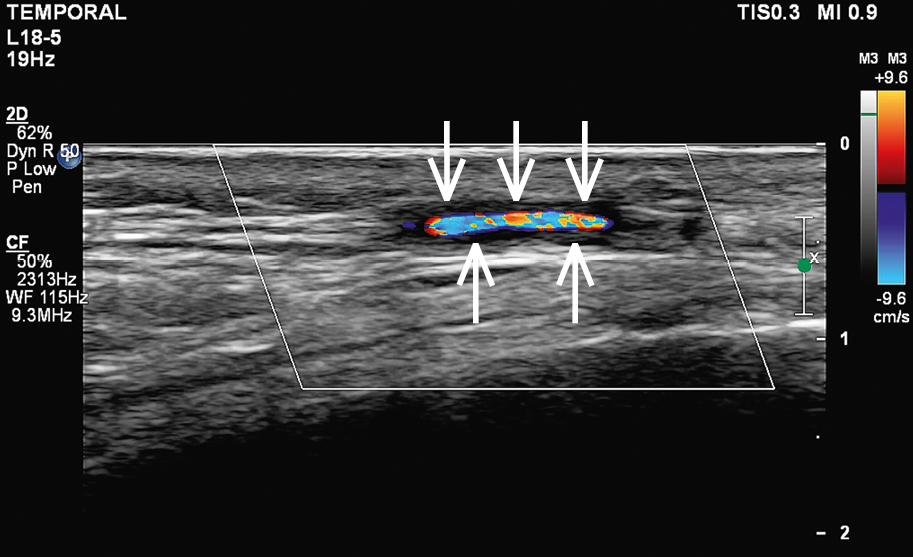

2. Imaging studies: Results depend on the location of lesions. Doppler ultrasonography (Figure 3) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may reveal inflammatory lesions in the temporal artery. Ultrasonography, conventional arteriography, computed tomography (CT), MRI, computed tomography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scanning may reveal lesions in the large arteries. Imaging studies also allow for detection of complications: aneurysms or arterial dissection.

3. Histologic examination of temporal artery biopsy specimens is the diagnostic gold standard, which in symptomatic patients may remain positive for months despite glucocorticoid treatment.Evidence 1High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Buttgereit F, Dejaco C, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B. Polymyalgia Rheumatica and Giant Cell Arteritis: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2016 Jun 14;315(22):2442-58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5444. Review. PubMed PMID: 27299619. It is usually performed within a few weeks (ideally no later than 14 days) after starting glucocorticoid treatment. A negative result does not exclude the diagnosis of GCA; however, patients rarely have a negative biopsy result and normal ESR.

Diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations and results of diagnostic tests. Establishing the diagnosis of GCA is easy in typical cases with temporal artery involvement. If the patient has been diagnosed with a form of vasculitis, it may be classified as temporal arteritis in those fulfilling ≥3 of 5 the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria:

1) Age ≥50 years.

2) New-onset localized headache.

3) Temporal artery tenderness or decreased pulsation.

4) ESR ≥50 mm/h.

5) Positive arterial biopsy results.

A diagnosis of temporal arteritis can be made in the setting of a high pretest probability supplemented by ultrasonography or MRI of a temporal artery and/or biopsy along with a rapid therapeutic response to prednisone. A positive biopsy result is not a prerequisite for diagnosis. This approach does not apply to and does not exclude the large-vessel presentation of aortitis/subclavian involvement, and the diagnosis of large-vessel GCA can be made with appropriate large-vessel imaging (CTA/MRA/PET) along with elevated ESR/CRP without the need for biopsy.

Differential Diagnosis

Other systemic vasculitides (see Vasculitis Syndromes).

TreatmentTop

1. Glucocorticoids: Consensus-based guidelines suggest that treatment should be oral prednisone 1 mg/kg/d (max, 60 mg/d) or an equivalent dose of another glucocorticoid continued until the resolution of symptoms and normalization of ESR (usually within 2-4 weeks; assess ESR after 1 week of treatment).Evidence 2Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the lack of high-quality experimental data. Buttgereit F, Dejaco C, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B. Polymyalgia Rheumatica and Giant Cell Arteritis: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2016 Jun 14;315(22):2442-58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5444. Review. PubMed PMID: 27299619. In patients with ophthalmic symptoms IV methylprednisolone 500 to 1000 mg for 3 consecutive days may be usedEvidence 3Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the lack of high-quality experimental data. Buttgereit F, Dejaco C, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B. Polymyalgia Rheumatica and Giant Cell Arteritis: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2016 Jun 14;315(22):2442-58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5444. Review. PubMed PMID: 27299619. (superiority of IV over oral administration of glucocorticoids has not been documented). Tapering is based on individual response to treatment. One possible method is to taper the dose of prednisone every 1 to 2 weeks by a maximum of 10% of the daily dose (usually up to 5-10 mg/d) and continue treatment for 1 to 2 years.Evidence 4Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the lack of high-quality experimental data. Buttgereit F, Dejaco C, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B. Polymyalgia Rheumatica and Giant Cell Arteritis: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2016 Jun 14;315(22):2442-58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5444. Review. PubMed PMID: 27299619. However, in many patients tapering of prednisone down to discontinuation is difficult. In case of recurring symptoms, use the last effective dose. Start osteoporosis prophylaxis (see Osteoporosis).

2. In patients at high risk for complications of glucocorticoid treatment (eg, with diabetes mellitus or severe hypertension), consider adding oral methotrexate 7.5 to 15 mg/wk to reduce the glucocorticoid dose.Evidence 5Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the lack of high-quality experimental data. Buttgereit F, Dejaco C, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B. Polymyalgia Rheumatica and Giant Cell Arteritis: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2016 Jun 14;315(22):2442-58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5444. Review. PubMed PMID: 27299619.

3. Tocilizumab has been recently shown to be more effective in comparison with prednisone.Evidence 6Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. Stone JH, Tuckwell K, Dimonaco S, et al. Trial of Tocilizumab in Giant-Cell Arteritis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 27;377(4):317-328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613849. PubMed PMID: 28745999. Another agent, abatacept, showed promising results.Evidence 7Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness and imprecision. Langford CA, Cuthbertson D, Ytterberg SR, et al; Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium. A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial of Abatacept (CTLA-4Ig) for the Treatment of Giant Cell Arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Apr;69(4):837-845. doi: 10.1002/art.40044. Epub 2017 Mar 3. PubMed PMID: 28133925; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5378642.

4. Long-term treatment with low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) may be considered if the patient is deemed at risk for cardiovascular disease.

FiguresTop

Figure 18.26-1. Giant cell arteritis.

Figure 18.26-2. Diagnostic algorithm for suspected giant cell arteritis involving temporal arteries.

Figure 18.26-3. Doppler ultrasonography of the temporal artery with features of inflammation. A visible halo sign: homogenous hypoechoic wall thickening clearly separated from the arterial lumen seen on transverse and longitudinal views, typically concentric (arrows).