Pearson GJ, Thanassoulis G, Anderson T, et al. 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults. Can J Cardiol. 2021 Aug;37(8):1129-1150. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.03.016. Epub 2021 Mar 26. PMID: 33781847.

Wong GC, Welsford M, Ainsworth C, et al; members of the Secondary Panel. 2019 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology Guidelines on the Acute Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Focused Update on Regionalization and Reperfusion. Can J Cardiol. 2019 Feb;35(2):107-132. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.11.031. PMID: 30760415.

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al; Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Circulation. 2018 Nov 13;138(20):e618-e651. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000617. Erratum in: Circulation. 2018 Nov 13;138(20):e652. PMID: 30571511.

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018 Jan 7;39(2):119-177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. PMID: 28886621.

Authors/Task Force members, Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014 Oct 1;35(37):2541-619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278. Epub 2014 Aug 29. PMID: 25173339.

Task Force Members, Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013 Oct;34(38):2949-3003. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht296. Epub 2013 Aug 30. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2014 Sep 1;35(33):2260-1. PMID: 23996286.

O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Jan 29;127(4):e362-425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. Epub 2012 Dec 17. Erratum in: Circulation. 2013 Dec 24;128(25):e481. PMID: 23247304.

Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2012 Dec 18;126(25):e354-471. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318277d6a0. Epub 2012 Nov 19. Erratum in: Circulation. 2014 Apr 22;129(16):e463. PMID: 23166211.

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD; Writing Group on the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction, Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012 Oct;33(20):2551-67. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184. Epub 2012 Aug 24. PMID: 22922414.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011 Dec 6;124(23):2574-609. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823a5596. Epub 2011 Nov 7. Erratum in: Circulation. 2012 Feb 28;125(8):e411. PMID: 22064598.

Abraham NS, Hlatky MA, Antman EM, et al; ACCF/ACG/AHA. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2010 expert consensus document on the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and thienopyridines: a focused update of the ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Dec 7;56(24):2051-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.010. PMID: 21126648.

Clinical Features and Natural History Top

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is an acute medical emergency caused by complete occlusion of a coronary artery leading to transmural ischemia. Typically, the occlusion is caused by a ruptured atherosclerotic plaque and subsequent thrombotic occlusion. If the occluded artery is not promptly revascularized, tissue infarction and myocardial scarring develop, often leading to decreased ventricular function. Thus, patients with a STEMI benefit from prompt restoration of blood flow to the affected myocardium through balloon angioplasty, coronary stenting, and/or less commonly coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), as well as medications that target the thrombotic occlusion.

STEMI most often occurs in the early morning hours. Some patients die before reaching hospital, mainly due to ventricular fibrillation (VF) and sudden cardiac death. In ~10% of cases symptoms are minor and the diagnosis is established only after a few days, weeks, or even months, on the basis of electrocardiography (ECG) and imaging studies. Elderly patients, women, and patients with diabetes are more likely to have atypical presentations.

1. Symptoms: Chest pain, epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, dyspnea, syncope, or palpitations.

2. Signs:

1) Skin pallor and sweating are usually associated with severe pain. Peripheral cyanosis and/or cool and mottled extremities are present in patients developing cardiogenic shock.

2) Tachycardia (most frequently >100 beats/min; heart rates decrease with relief of pain), arrhythmia (most frequently premature ventricular complexes), bradycardia (in 10% of patients frequent in inferior wall myocardial infarction [MI]).

3) Abnormal heart sounds: Gallop sounds (S4), frequently a transient systolic murmur caused by a dysfunctional ischemic papillary muscle (more frequently in inferior wall MI) or left ventricular (LV) dilatation. A sudden-onset, loud apical systolic murmur accompanied by a thrill, most frequently caused by papillary muscle rupture (usually accompanied by symptoms of shock); a similar murmur, although most prominent along the left sternal border, occurs in ventricular septal rupture. Pericardial friction rub may be heard in large MIs (usually on day 2 or 3); it is associated with a postinfarction pericarditis.

4) Rales are audible over the lungs in patients with LV failure.

5) Symptoms of right ventricular failure, including hypotension and jugular venous distention, in right ventricular MI (it may accompany inferior wall MI).

Diagnosis Top

1. ECG:

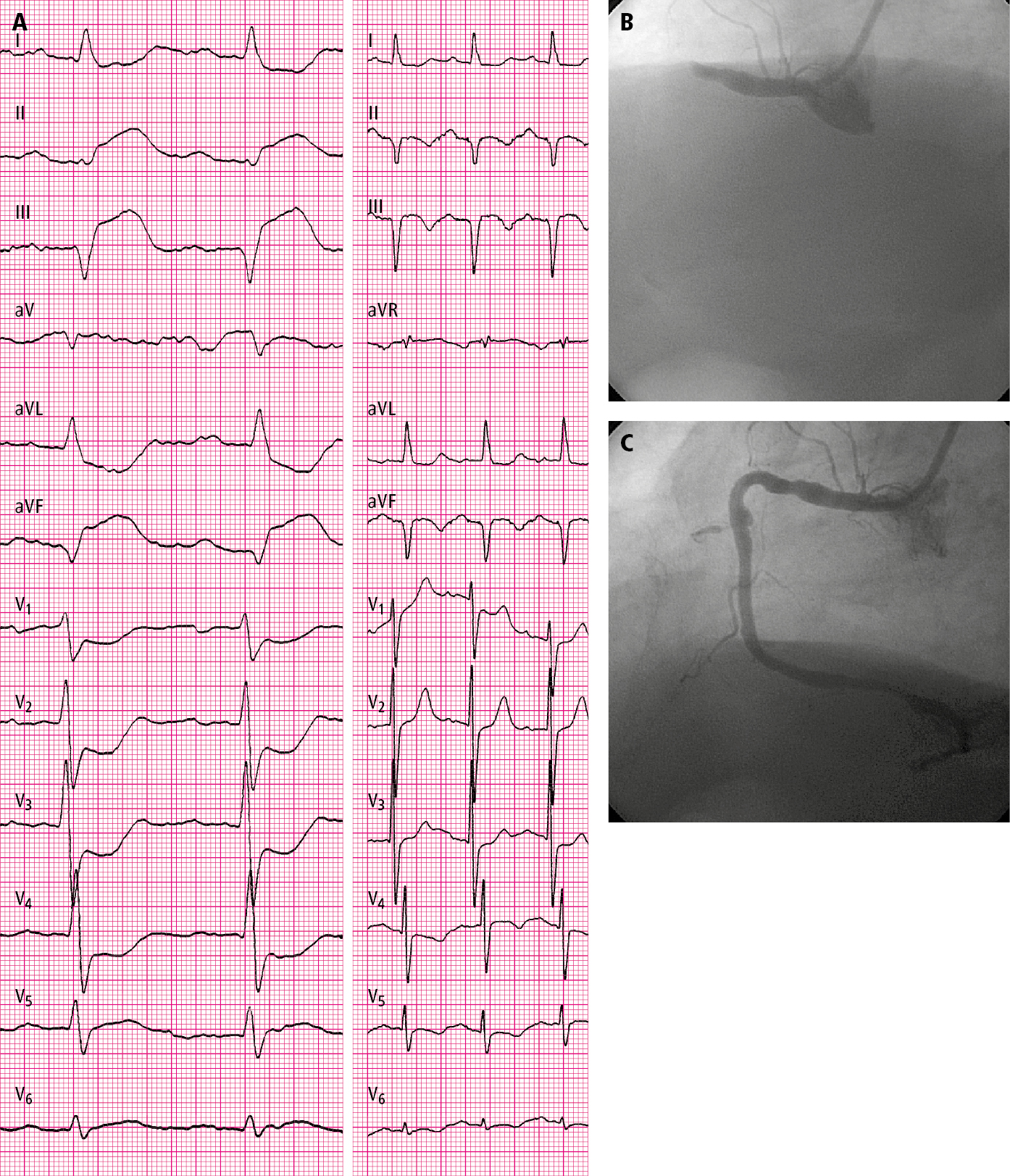

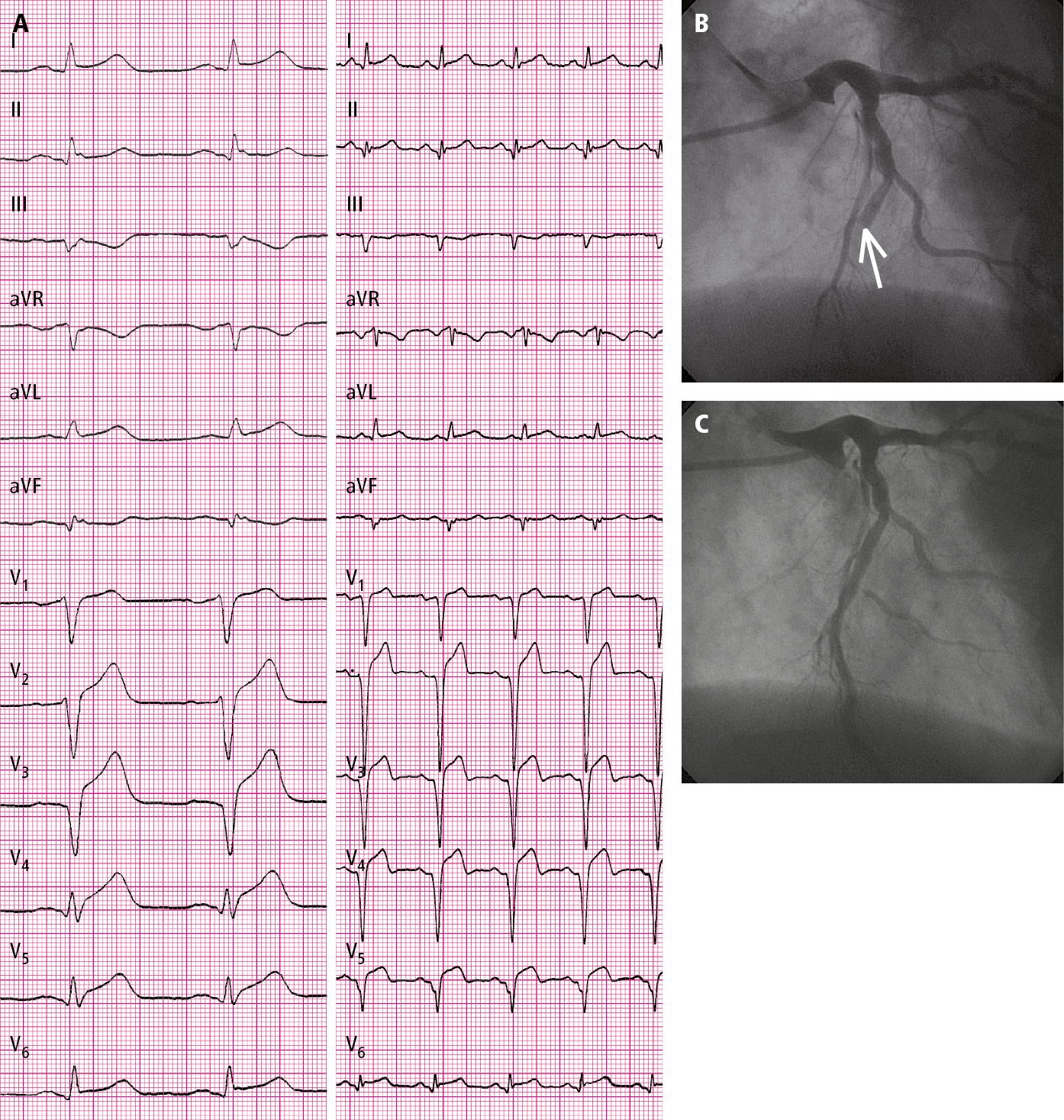

1) Diagnostic ECG criteria for STEMI (Figure 1, Figure 2): A persistent ST-segment elevation at the J point in 2 contiguous leads with the following cutoff points:

a) >0.1 mV in all leads other than leads V2 to V3.

b) For leads V2 to V3, the following cutoff points apply: ≥0.2 mV in men aged ≥40 years, ≥0.25 mV in men aged <40 years, or ≥0.15 mV in women.

2) New-onset left bundle branch block (LBBB) on its own is no longer considered specific for STEMI. Acute MI is suggested in patients with LBBB and an ST-segment elevation ≥1 mm that is in the same direction (concordant) as the QRS complex in any lead or an ST-segment depression of ≥1 mm in any lead from V1 to V3, or an ST-segment elevation ≥5 mm that is discordant with the QRS complex; MI may be also suspected if there is a QS complex in leads V1 to V4 and a Q wave in leads V5 and V6. Other criteria (Barcelona criteria, modified Sgarbossa criteria) may have improved accuracy.Evidence 1Moderate Quality of Evidence(moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness and the risk of bias. Sgarbossa EB, Pinski SL, Barbagelata A, et al. Electrocardiographic diagnosis of evolving acute myocardial infarction in the presence of left bundle-branch block. GUSTO-1 (Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996 Feb 22;334(8):481-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602223340801. Erratum in: N Engl J Med 1996 Apr 4;334(14):931. PMID: 8559200. Di Marco A, Rodriguez M, Cinca J, et al. New Electrocardiographic Algorithm for the Diagnosis of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients With Left Bundle Branch Block. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Jul 21;9(14):e015573. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015573. Epub 2020 Jul 4. Erratum in: J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Nov 17;9(22):e014618. PMID: 32627643; PMCID: PMC7660719. Smith SW, Dodd KW, Henry TD, Dvorak DM, Pearce LA. Diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the presence of left bundle branch block with the ST-elevation to S-wave ratio in a modified Sgarbossa rule. Ann Emerg Med. 2012 Dec;60(6):766-76. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.07.119. Epub 2012 Aug 31. Erratum in: Ann Emerg Med. 2013 Oct;62(4):302. PMID: 22939607.

3) Typical evolution of ECG changes lasts several hours to several days. The initial appearance of tall peaked T waves is followed by a convex or horizontal ST-segment elevation. Then pathologic Q waves with reduced R waves appear (Q waves may be absent in patients with a small MI or those undergoing reperfusion therapy), the ST segment returns to the isoelectric line, and the amplitudes of R waves decrease further. Q waves become deeper, and inverse T waves appear. A new R wave in lead V1 should be followed by a 15-lead posterior ECG, as it may reflect a posterior Q wave and infarction. The probable location of MI based on ECG changes: Table 1.

2. Blood tests should not be used for the acute diagnosis of STEMI because this would delay acute reperfusion and the initial cardiac biomarker measurement may be normal. In acute MI elevated blood levels of markers of myocardial necrosis can be seen:

1) Cardiac-specific troponin T (cTnT) levels 10 to 14 ng/L (depending on assay), cardiac-specific troponin I (cTnI) levels 9 to 70 ng/L (depending on assay).

2) Creatine kinase MB (CK-MB) concentration (CK-MBmass) >5 to 10 microg/L (depending on assay); this is used only when cTn measurements are not available.

3) CK-MB activity and myoglobin concentrations are no longer used in the diagnostic workup of MI.

3. Chest radiography may reveal signs of other diseases that may have caused angina, or features of heart failure. Note of a widened mediastinum should be made, as aortic dissection may present with similar symptoms or can dissect down a coronary artery and cause a STEMI.

4. Resting echocardiography may reveal regional wall-motion abnormalities or other etiologies of chest pain, such as valvular heart disease including aortic stenosis or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

5. Rapid coronary angiography (Figure 1, Figure 2) reveals lesions located in the coronary arteries that are responsible for STEMI (usually arterial occlusion) and allows reperfusion (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]).Evidence 2Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003 Jan 4;361(9351):13-20. Review. PubMed PMID: 12517460.

In patients presenting with acute chest pain, the differential diagnosis includes—but is not limited to—aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, myopericarditis, or musculoskeletal chest pain (see Chest Pain). The presence of certain characteristics markedly increases the probability of ACS as opposed to other causes: features similar to current symptoms documented before as related to CAD; known history of MI; transient hypotension, diaphoresis, pulmonary congestion, or mitral regurgitation murmur; presumably new dynamic changes of ST-segment deviation (≥1 mm) or T-wave inversion in multiple precordial leads; elevated cardiac markers.

Treatment Top

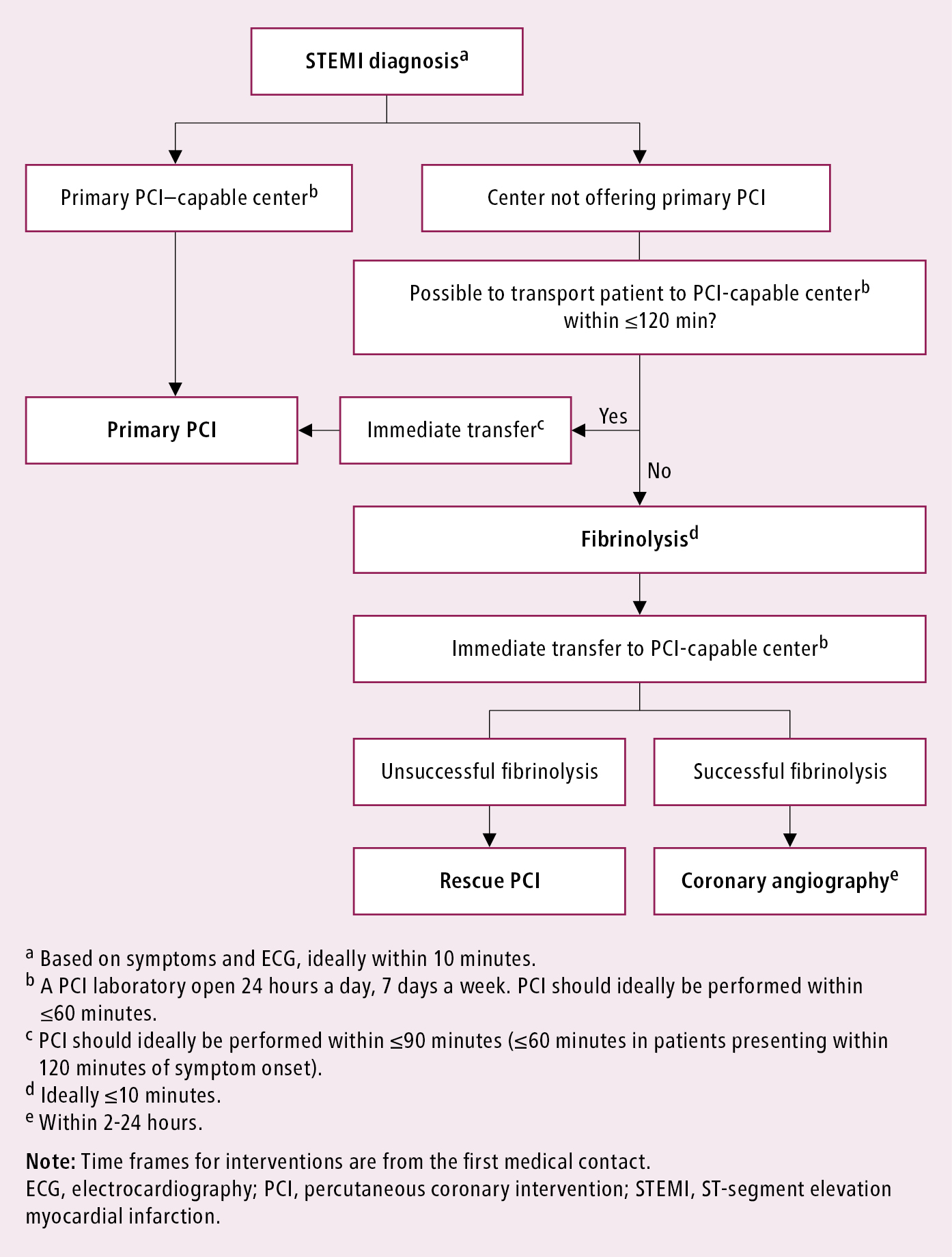

Management algorithm: Figure 3.

1. Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) 160 mg to chew should be administered by emergency personnel to every patient with suspected MI, unless there are contraindications or the patient has previously taken ASA on their own.

2. Prehospital ECG: If the prehospital ECG confirms the diagnosis of STEMI, when possible and practical these patients should be brought to a center capable of primary PCI as long as the time from contact to PCI is <120 minutes.Evidence 3Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Boersma E; Primary Coronary Angioplasty vs. Thrombolysis Group. Does time matter? A pooled analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing primary percutaneous coronary intervention and in-hospital fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction patients. Eur Heart J. 2006 Apr;27(7):779-88. Epub 2006 Mar 2. PubMed PMID: 16513663.

3. In areas where timely primary PCI is not available, prehospital fibrinolysis should be considered if possible within the existing systems of care.Evidence 4Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Morrison LJ, Verbeek PR, McDonald AC, Sawadsky BV, Cook DJ. Mortality and prehospital thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000 May 24-31;283(20):2686-92. PubMed PMID: 10819952.

Patients should be treated at a coronary care unit or an equivalent monitored unit for ≥24 hours. Then patients may be moved to a step-down monitored bed for the subsequent 24 to 48 hours. Patients may be transferred to a regular ward only after 12 to 24 hours of clinical stability, that is, no signs or symptoms of myocardial ischemia, heart failure, or arrhythmias with hemodynamic consequences.

1. Oxygen should be administered to every patient with hypoxia (arterial saturation [SpO2] <90%) and monitored using pulse oximetry. Routine administration of supplemental oxygen for patients with SpO2 possibly as low as ≥90% and certainly >94% should be avoided.Evidence 5Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. Chu DK, Kim LH, Young PJ, et al. Mortality and morbidity in acutely ill adults treated with liberal versus conservative oxygen therapy (IOTA): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018 Apr 28;391(10131):1693-1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30479-3. Epub 2018 Apr 26. Review. PubMed PMID: 29726345.

2. Nitrates: Sublingual nitroglycerin (0.4 mg every 5 minutes as long as the pain persists and as long as no significant adverse effects develop, up to a total of 3 doses), subsequently continued via an IV route (dosage: see Non–ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction) in patients with persistent symptoms of myocardial ischemia (particularly pain), heart failure, significantly elevated blood pressures (do not use routinely in the early phase of STEMI). Contraindications to the use of nitrates in patients with STEMI: systolic blood pressure (SBP) <90 mm Hg, tachycardia >100 beats/min (in patients without heart failure), suspected right ventricular MI, administration of a phosphodiesterase inhibitor within the prior 24 hours (for sildenafil or vardenafil) or 48 hours (for tadalafil).Evidence 6Weak recommendation (downsides likely outweigh benefits, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the observational nature of data and indirectness of the population and outcomes measured. Kloner RA, Hutter AM, Emmick JT, Mitchell MI, Denne J, Jackson G. Time course of the interaction between tadalafil and nitrates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003 Nov 19;42(10):1855-60. PubMed PMID: 14642699.

3. Morphine is the analgesic of choice in STEMI. Administer 4 to 8 mg IV with subsequent injections of 2 mg every 5 to 15 minutes until the resolution of pain (in some patients the total dose required to control the pain is as high as 2 mg/kg and is well tolerated). Adverse effects include nausea and vomiting, hypotension with bradycardia, and respiratory depression. There is some evidence that morphine may reduce absorption and effects of oral P2Y12 inhibitors.

4. Antiplatelet agents: ASA, administered immediately with the first medical contact, whether in the field with the emergency medical service or in the emergency department, and P2Y12 inhibitors should be used (ticagrelor, prasugrel, or clopidogrel). The choice of a P2Y12 inhibitor should be discussed, if possible, with an interventional cardiologist. In general, more potent long-term agents (ticagrelor or prasugrel) are associated with reduced rates of ischemic events and stent thrombosis. Additional remarks on the choice of P2Y12 inhibitors:

1) Prasugrel or ticagrelor (rather than clopidogrel) are preferred in patients undergoing primary PCIEvidence 7Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al; PLATO Investigators, Freij A, Thorsén M. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009 Sep 10;361(11):1045-57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. Epub 2009 Aug 30. PubMed PMID: 19717846. Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al; TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007 Nov 15;357(20):2001-15. Epub 2007 Nov 4. PubMed PMID: 17982182; for ticagrelor, use a loading dose of 180 mg and then 90 mg bid, and for prasugrel, use a loading dose of 60 mg and then 10 mg daily. Prasugrel should not be used in patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), body weight <60 kg, or age >75 years. It is not currently available in Canada. Neither prasugrel nor ticagrelor should be used in patients suspected of having surgical coronary artery disease (CAD), as this may delay eligibility for CABG.Evidence 8Weak recommendation (downsides likely outweigh benefits, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al; TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007 Nov 15;357(20):2001-15. Epub 2007 Nov 4. PubMed PMID: 17982182.

2) Clopidogrel may be used in patients undergoing primary PCI (if prasugrel and ticagrelor are not available) or if at higher bleeding risk. In patients treated with fibrinolysis, use a loading dose of 300 mg of clopidogrel in patients aged ≤75 years and 75 mg for those aged >75 years.Evidence 9Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, et al; CLARITY-TIMI 28 Investigators. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 24;352(12):1179-89. Epub 2005 Mar 9. PubMed PMID: 15758000.

3) Ticagrelor may be administered in patients who have received fibrinolysis,Evidence 10Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. Berwanger O, Nicolau JC, Carvalho AC, et al; TREAT Study Group. Ticagrelor vs Clopidogrel After Fibrinolytic Therapy in Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018 May 1;3(5):391-399. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0612. Erratum in: JAMA Cardiol. 2018 May 1;3(5):445. PubMed PMID: 29525822; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5875327. with the understanding that this was a strategy tested in patients <75 years of age within 24 hours of the beginning of symptoms and an approximate median time from fibrinolysis of 8 to 10 hours.

5. Beta-blockers should be used in patients without contraindications, such as bradycardia, Killip class II or greater heart failure, or active bronchospasm.Evidence 11Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Ibanez B, Macaya C, Sánchez-Brunete V, et al. Effect of early metoprolol on infarct size in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: the Effect of Metoprolol in Cardioprotection During an Acute Myocardial Infarction (METOCARD-CNIC) trial. Circulation. 2013 Oct 1;128(14):1495-503. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003653. Epub 2013 Sep 3. PubMed PMID: 24002794. Bangalore S, Makani H, Radford M, et al. Clinical outcomes with β-blockers for myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Med. 2014 Oct;127(10):939-53. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.05.032. Epub 2014 Jun 11. PubMed PMID: 24927909. In patients in whom beta-blockers are contraindicated and in whom suppression of heart rate is necessary because of atrial fibrillation (AF), atrial flutter, or persistent myocardial ischemia, a calcium channel blocker (diltiazem and verapamil) may be used unless LV systolic dysfunction or atrioventricular (AV) block is present (calcium channel blockers should not be used routinely in patients with STEMI). Patients with baseline contraindications to beta-blockers should be monitored for possible resolution of the contraindications in the course of hospital treatment, as this may allow the start of long-term beta-blocker treatment. Dosage of oral agents, contraindications, and adverse effects: see Stable Angina Pectoris.

6. Anticoagulants: The choice and dosage depend on the treatment method of STEMI: PCI, CABG, fibrinolysis, or no reperfusion treatment (see below).

7. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs): Start as early as day 1 of MI unless contraindicated, particularly in patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40% or symptoms of heart failure in the early phase of STEMI.Evidence 12Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Rodrigues EJ, Eisenberg MJ, Pilote L. Effects of early and late administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality after myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2003 Oct 15;115(6):473-9. PubMed PMID: 14563504. Start with low doses and then titrate up, depending on tolerance. In the case of ACEI intolerance (cough), switch to an angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB). Dosage: see Table 4 in Stable Angina Pectoris.

8. Statins are used in every patient regardless of plasma cholesterol levels, unless contraindicated, preferably within 1 to 4 days of admission. The target low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels are <1.8 mmol/L or 70 mg/dL (<1.4 mmol/L [55 mg/dL] according to the European Society of Cardiology [ESC]).

9. Antilipid therapies: In the longer term, ezetimibe can be added to statin therapy to meet lipid goals. Recent evidence supports the use of PCSK9 inhibitors for secondary prevention in patients with CAD and LDL-C levels >1.8 mmol/L (target in Canadian guidelines; >1.4 mmol/L according to the ESC) despite the use of statin therapy. Cost and access may limit the use of these therapies.

1. Primary PCI is indicated if the time from the first medical contact to PCI is <120 minutesEvidence 13Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Terkelsen CJ, Christiansen EH, Sorensen JT, et al. Primary PCI as the preferred reperfusion therapy in STEMI: it is a matter of time. Heart. 2009 Mar;95(5):362-9. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.139493. Review. PubMed PMID: 19218262. Boersma E; Primary Coronary Angioplasty vs. Thrombolysis Group. Does time matter? A pooled analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing primary percutaneous coronary intervention and in-hospital fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction patients. Eur Heart J. 2006 Apr;27(7):779-88. Epub 2006 Mar 2. PubMed PMID: 16513663.; otherwise administer fibrinolysis unless contraindicated.Evidence 14Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Pinto DS, Frederick PD, Chakrabarti AK, et al; National Registry of Myocardial Infarction Investigators. Benefit of transferring ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients for percutaneous coronary intervention compared with administration of onsite fibrinolytic declines as delays increase. Circulation. 2011 Dec 6;124(23):2512-21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.018549. Epub 2011 Nov 7. PubMed PMID: 22064592. Primary PCI is indicated in the case of:

1) All patients with an indication for reperfusion therapy: chest pain or discomfort lasting <12 hours and persistent ST-segment elevation.

2) Patients with shock or contraindications to thrombolytic therapy (see below), regardless of the time since the onset of MI.

3) Evidence of ongoing myocardial ischemia even if symptoms of MI appeared >12 hours earlier or if the pain and ECG changes have been stuttering.Evidence 15Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity of the studied populations. Abbate A, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Appleton DL, et al. Survival and cardiac remodeling benefits in patients undergoing late percutaneous coronary intervention of the infarct-related artery: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Mar 4;51(9):956-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.062. Epub 2008 Feb 6. PubMed PMID: 18308165.

2. Rescue PCI is indicated after failed fibrinolysis, that is, when clinical symptoms and ST-segment elevations have not resolved (<50% reduction in the ST-segment elevation) within 60 to 90 minutes of the initiation of fibrinolysis; PCI should be considered as soon as possible.

3. A pharmacoinvasive approach should be used in patients without contraindications, with coronary angiography and/or PCI performed within 3 to 24 hours of successful fibrinolysis.Evidence 16Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Cantor WJ, Fitchett D, Borgundvaag B, et al; TRANSFER-AMI Trial Investigators. Routine early angioplasty after fibrinolysis for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jun 25;360(26):2705-18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808276. PubMed PMID: 19553646.

4. Indications for CABG:

1) Coronary anatomy best treated with CABG and Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI)-3 flow of the infarct vessel.

2) Cardiogenic shock in a patient with left main or multivessel CAD.

3) Mechanical complications of MI.

5. Anticoagulant therapy in patients treated with primary PCI: There are alternatives and, at the discretion of the person performing the procedure, the choice and combination of which to use depends on the perceived bleeding risk as compared with the thrombotic risk and concomitant use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists.Evidence 17Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness of applying results to individual patients, as the balance of risks of competing outcomes is difficult to establish. Cavender MA, Sabatine MS. Bivalirudin versus heparin in patients planned for percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014 Aug 16;384(9943):599-606. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61216-2. PubMed PMID: 25131979. Shahzad A, Kemp I, Mars C, et al; HEAT-PPCI trial investigators. Unfractionated heparin versus bivalirudin in primary percutaneous coronary intervention (HEAT-PPCI): an open-label, single centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014 Nov 22;384(9957):1849-58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60924-7. Epub 2014 Jul 4. Erratum in: Lancet. 2014 Nov 22;384(9957):1848. PubMed PMID: 25002178. Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, et al; HORIZONS-AMI Trial Investigators. Bivalirudin during primary PCI in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008 May 22;358(21):2218-30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708191. PubMed PMID: 18499566.

1) Unfractionated heparin (UFH) in an IV injection at a standard dose of 70 to 100 IU/kg (or 50-60 IU/kg in patients treated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists).

2) Bivalirudin in an IV injection 0.75 mg/kg, followed by an IV infusion 1.75 mg/kg/h (regardless of the activated clotting time [ACT]) for the duration of the procedure.

3) Enoxaparin in an IV injection 0.5 mg/kg. Do not use fondaparinux during primary PCI.

1. Indications: Patients in whom primary PCI cannot be performed within the recommended timeframe (time from the first medical contact to PCI >120 minutes).

2. Contraindications: Absolute contraindications to fibrinolysis: history of intracranial hemorrhage or stroke of unknown origin; ischemic stroke in the last 3 months; cerebral vascular lesion, central nervous system injury or intracranial malignancy; recent major trauma, surgery, or head injury in the last 3 weeks; known bleeding disorder; aortic dissection; noncompressible punctures in the past 24 hours (eg, liver biopsy, lumbar puncture). Relative contraindications: TIA in the last 3 months; oral anticoagulant therapy; pregnancy; first week post partum; prior internal bleeding in the last 2 to 4 weeks; traumatic cardiopulmonary resuscitation; treatment-refractory hypertension (SBP >180 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure >110 mm Hg); advanced liver disease; infective endocarditis; active peptic ulcer.

3. Fibrinolytic agents and concomitant anticoagulants: Table 4. Fibrinolytic agents should be started within 30 minutes of the arrival of emergency medical services or of the patient’s arrival at the hospital. Fibrin-specific agents (alteplase, tenecteplase) are preferred; never administer streptokinase to a patient who has been previously treated with streptokinase or anistreplase due to its immunogenic properties and risk of reactions including anaphylaxis.

Patients who receive fibrin-specific agents should be treated with fondaparinux,Evidence 18Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Yusuf S, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, et al; OASIS-6 Trial Group. Effects of fondaparinux on mortality and reinfarction in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the OASIS-6 randomized trial. JAMA. 2006 Apr 5;295(13):1519-30. Epub 2006 Mar 14. PubMed PMID: 16537725. concomitant UFH, or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH).Evidence 19Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Eikelboom JW, Quinlan DJ, Mehta SR, Turpie AG, Menown IB, Yusuf S. Unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin as adjuncts to thrombolysis in aspirin-treated patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of the randomized trials. Circulation. 2005 Dec 20;112(25):3855-67. Epub 2005 Dec 12. PubMed PMID: 16344381. Patients receiving streptokinase should not receive UFHEvidence 20Strong recommendation (downsides clearly outweigh benefits; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Eikelboom JW, Quinlan DJ, Mehta SR, Turpie AG, Menown IB, Yusuf S. Unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin as adjuncts to thrombolysis in aspirin-treated patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of the randomized trials. Circulation. 2005 Dec 20;112(25):3855-67. Epub 2005 Dec 12. PubMed PMID: 16344381. and should be treated with fondaparinux. Fondaparinux is associated with reduced bleeding compared to enoxaparin. Every patient should also receive antiplatelet therapy: ASA and clopidogrel (not ticagrelor or prasugrel; see above). Ticagrelor may be started 12 to 24 hours after fibrinolysis and appears to be safe and effective.

4. Complications of fibrinolysis most frequently include bleeding; in the case of streptokinase, allergic reactions may also develop. If you suspect intracranial bleeding, discontinue all fibrinolytic, anticoagulant, and antiplatelet agents immediately. Then perform imaging studies (eg, computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] of the head) and laboratory tests (hematocrit, hemoglobin, prothrombin time [PT], activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT], platelet count, fibrinogen and D-dimer levels; repeat these studies as needed) and request an urgent neurosurgical consultation. Give 2 units of fresh frozen plasma every 6 hours for 24 hours plus platelet concentrate when necessary, as well as protamine in patients who have received UFH (dosage: see Heparins).

5. Indications for coronary angiography in patients receiving fibrinolytic treatment:

1) Lack of reperfusion (<50% resolution of ST-segment elevation at 60-90 minutes), then emergency rescue PCI.Evidence 21Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the relatively small number of events. Gershlick AH, Stephens-Lloyd A, Hughes S, et al; REACT Trial Investigators. Rescue angioplasty after failed thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2005 Dec 29;353(26):2758-68. PubMed PMID: 16382062.

2) Within 3 to 24 hours of the beginning of successful fibrinolysis (as evidenced by ST-segment resolution by >50% at 60-90 minutes, typical reperfusion arrhythmia, or disappearance of chest pain) in high-risk patients (anterior MI or high-risk inferior MI).Evidence 22Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Cantor WJ, Fitchett D, Borgundvaag B, et al; TRANSFER-AMI Trial Investigators. Routine early angioplasty after fibrinolysis for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jun 25;360(26):2705-18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808276. PubMed PMID: 19553646.

3) In patients with low-risk STEMI (inferior MI without high-risk features), consider coronary angiography.

Management of Patients Who Have Not Received Reperfusion Therapy

1. In addition to the drugs indicated in all patients with STEMI (see above), including the antiplatelet agents (ASA and clopidogrel), administer an anticoagulant: fondaparinux; if fondaparinux is not available, use enoxaparin or UFH (dosage: Table 4).

2. Coronary angiography should be performed immediately in hemodynamically unstable patients. In stable patients it may be considered before discharge. Administer IV UFH in a bolus of 60 IU/kg (up to a maximum of 4000 IU) prior to PCI.

Management of Nonculprit Lesions in CAD

Unlike most patients with stable CAD, those with STEMI and multivessel CAD benefit from PCI of nonculprit lesions. In a completed trial such interventions decreased the long-term risk of cardiovascular death and recurrent MI.Evidence 23High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Mehta SR, Wood DA, Storey RF, et al; COMPLETE Trial Steering Committee and Investigators. Complete Revascularization with Multivessel PCI for Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 10;381(15):1411-1421. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1907775. Epub 2019 Sep 1. PMID: 31475795. Nonculprit revascularization can occur during the index catheterization or within 4 weeks, depending on lesion complexity and local resources. An interventional cardiology team should be consulted to establish these decisions.

ComplicationsTop

Complications of MI:

1. Acute heart failure due to extensive myocardial necrosis and ischemia, arrhythmias/conduction disturbances, or mechanical complications of MI. Symptoms and treatment: see Acute Heart Failure.

2. Recurrent ischemia or MI:

1) In patients with recurrent ST-segment elevation, perform emergency coronary angiography.

2) In patients with recurrent chest pain after reperfusion therapy, intensify medical treatment with nitrates and beta-blockers. Patients may require IV nitroglycerin infusion. Repeat ECG as a test for stent thrombosis is important and repeat angiography may be required. Administer heparin (unless already started earlier).

3) Patients with signs of hemodynamic instability should be urgently referred for cardiac catheterization.

3. Free wall rupture usually develops within 5 days of STEMI; it rarely occurs in patients with LV hypertrophy or well-developed collateral circulation. Patients may present with transient syncope after straining on the toilet. Signs of acute rupture include cardiac tamponade and cardiac arrest, usually with fatal outcome. Symptoms of slowly progressing rupture are consistent with developing cardiac tamponade and symptoms of shock. Diagnosis is based on echocardiography. Treatment: Urgent surgical intervention.

4. Ventricular septal rupture (VSR) usually develops on days 3 to 5 of MI. Signs: A new-onset holosystolic murmur heard along the left sternal border (it may be poorly audible in patients with large ruptures) and rapidly worsening symptoms of left and right ventricular failure. Diagnosis is based on echocardiography. Treatment: Management of shock, including intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation and invasive hemodynamic monitoring; surgery must be performed as soon as possible (this usually involves resection of the necrotic tissues and closing the defect with a prosthetic patch).

5. Papillary muscle rupture develops on days 2 to 10 of MI; it is most frequently associated with inferior wall MI and affects the posteromedial LV papillary muscle, causing acute mitral regurgitation. Signs: Acute heart failure; a typical loud holosystolic apical murmur that may have widespread radiation; in many patients, there is absence of murmur or only a soft murmur due to the lack of pressure gradient between the left ventricle and left atrium. Diagnosis is based on clinical features confirmed by echocardiography. Treatment: Surgery, usually mitral valve replacement. Mitral regurgitation may also occur as a result of dilatation of the mitral annulus and ischemic dysfunction of the subvalvular apparatus without mechanical damage; in such cases, PCI may be the treatment of choice. Afterload reduction with an intra-aortic balloon pump or nitroprusside may help decrease regurgitant ejection fraction if blood pressure tolerates in a critical care unit.

6. Arrhythmias and conduction disturbances: In addition to specific treatment (see below), correct electrolyte disturbances (target potassium levels >4 mmol/L and magnesium levels >1 mmol/L) and acid-base disturbances, if present.

1) Ventricular premature beats (VPBs) are very common on day 1 of MI; they generally do not require antiarrhythmic treatment unless they cause hemodynamic deterioration. A routine prophylactic use of antiarrhythmic drugs (eg, lidocaine) is not recommended.

2) Accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR) (<120 beats/min) is relatively common on day 1 of MI; it usually does not require the administration of antiarrhythmic drugs. AIVR is not associated with an increased risk of ventricular fibrillation. It may be a sign of successful reperfusion.

3) Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) does not usually have hemodynamic consequences and does not require specific treatment. In the later phases of MI, particularly in patients with reduced LVEF, it may indicate an increased risk of cardiac arrest and may require pharmacologic treatment and diagnostic workup as in sustained ventricular tachycardia.

4) Sustained VT:

a) Polymorphic VT: The most common cause of polymorphic VT in patients with acute MI is ischemia. Prompt defibrillation (as in VF) is indicated if the patient is unstable. If the patient is stable, pharmacologic conversion with amiodarone or lidocaine can be attempted. In the event of bradycardia or QT prolongation as the cause of polymorphic VT, temporary pacing can be attempted. Magnesium sulfate can be helpful in preventing recurrence of torsades des pointes (polymorphic VT due to prolonged QT interval).

b) Monomorphic VT: Perform cardioversion if the patient is unstable. In patients who tolerate VT well (SBP >90 mm Hg, no angina or pulmonary edema), pharmacotherapy with intravenous beta-blockers (drugs of choice) may be attempted before cardioversion, but such treatment rarely leads to the resolution of tachycardia. Alternatives include amiodarone 150 mg (or 5 mg/kg) in an IV infusion over 10 minutes, and repeat every 10 to 15 minutes when necessary (alternatively, 360 mg over 6 hours [1 mg/min], followed by 540 mg over the subsequent 18 hours [0.5 mg/min]; total dose ≤1.2 g/d); lidocaine 1 mg/kg in an IV injection, followed by 0.5 mg/kg every 8 to 10 minutes, up to a maximum of 4 mg/kg; alternatively, 1 to 3 mg/min in an IV infusion.

5) VF: Defibrillation. Primary VF (within 4 hours of hospitalization) is not associated with a poorer long-term prognosis in patients surviving the hospital phase of MI. In patients with sustained VT or VF occurring after the first 48 hours of hospitalization, consider a consultation with an electrophysiologist regarding an implantable defibrillator (ICD) (indications for ICD implantation after MI: see Ventricular Arrhythmia Following Myocardial Infarction).

6) AF is more frequent in the elderly, in patients with anterior MI, extensive myocardial necrosis, heart failure, other arrhythmias, and conduction disturbances or post-MI pericarditis. It is an adverse prognostic factor.

a) Persistent AF causing hemodynamic consequences or symptoms of myocardial ischemia: Cardioversion. If cardioversion is ineffective, use antiarrhythmic agents controlling ventricular rate (IV amiodarone or IV digoxin in patients with heart failure).

b) Persistent AF with no hemodynamic consequences or symptoms of myocardial ischemia: Antiarrhythmic agents controlling ventricular rate. Consider the indications for anticoagulant therapy.

7) Bradyarrhythmias:

a) Symptomatic sinus bradycardia, sinus pauses >3 seconds, or sinus bradycardia <40 beats/min with hypotension and symptoms of hemodynamic impairment: IV atropine 0.5 to 1 mg (up to a maximum dose of 2 mg). In patients with persistent disturbances, temporary cardiac pacing.

b) First-degree AV block (see Atrial Fibrillation): No treatment.

c) Second-degree AV block (Wenckebach type) with hemodynamic disturbances: Atropine; if ineffective, temporary cardiac pacing.

d) Mobitz type II second-degree AV block or third-degree AV block: Temporary cardiac pacing is usually indicated; it may be avoided in patients with ventricular rates >50 beats/min, narrow QRS complexes, and no signs of hemodynamic instability.

Usually heart block is transient after MI and typically does not require permanent pacing. Indications for permanent cardiac pacing: see Atrioventricular Blocks.

7. Stroke usually occurs after 48 hours of hospitalization. Predisposing factors include a prior stroke or TIA, CABG, advanced age, low LVEF, AF, and hypertension. If the stroke is caused by emboli originating from the heart (AF, intracardiac thrombi, akinetic LV segments), start a DOAC or VKA when safe, preferably after consultation with a neurologist or stroke specialist. The start of DOAC or VKA treatment can vary and is typically delayed if there is a moderate to large area of ischemic brain injury. Also remember that a full anticoagulant effect occurs within 4 to 6 days after starting a VKA, whereas it is almost immediate (within 1-3 hours) after starting a DOAC. Initiating anticoagulant therapy too early after a presumed cardioembolic ischemic stroke can increase the risk for hemorrhagic transformation with the potential to worsen a neurologic deficit.

Rehabilitation Top

Patients with STEMI should be referred to an outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program where feasible. This may include an exercise program, dietary advice, and smoking cessation programs.

Prognosis Top

Discharge Planning: Risk Stratification, Prognosis, Management

Mortality of patients with uncomplicated STEMI who have undergone primary PCI is between 2% and 5%. The TIMI risk score (Table 5) or the Zwolle risk score (Table 7) can be used to determine the risk and timing of discharge. The probability of 30-day and 1-year mortality ranges from about 2% and 4%, respectively, for Zwolle scores 0 to 3; 4% and 7% for scores 4 to 6; 10% and 20% for scores 7 to 9; and 30% and 40% for a score >10. In low-risk patients (a Zwolle risk score ≤3), early discharge at 48 to 72 hours is feasible.

For the purpose of assessing prognosis, a TIMI classification system is used. The system describes coronary artery flow following revascularization. TIMI flow 0 means no perfusion, TIMI 1 means only faint flow with incomplete filling of the distal arteries, TIMI 2 means complete filling but with sluggish flow, and TIMI 3 means normal flow. For Killip class, Killip class IV means cardiogenic shock, Killip class III means acute pulmonary edema (crackles in >50% of the lung fields), Killip class II means signs of heart failure (crackles in <50% of the lung fields), and Killip class I represents no heart failure.

In patients not treated with coronary revascularization procedures, the risk of death or MI should be assessed in the context of indications for coronary angiography and subsequent invasive treatment.

1. Prior to discharge, assess the risk of death or recurrent MI. As indicated above, one of the tools for early risk assessment is the TIMI STEMI score (Table 5; also available at mdcalc.com).

2. Indications for coronary angiography without prior stress testing after the acute period:

1) Symptoms of myocardial ischemia that develop spontaneously or with minimal effort in the post-MI recovery period, or persistent hemodynamic instability.

2) Before radical treatment of mechanical complications of STEMI in patients with acceptable hemodynamic stability.

3. Do not perform the stress test:

1) Within 2 to 3 days of the onset of STEMI in patients who did not undergo successful reperfusion therapy.

2) In patients with unstable post-MI angina, symptomatic heart failure, or life-threatening arrhythmias.

4. Do not perform coronary angiography in patients who are not candidates for revascularization because of specific contraindications or lack of consent.

Follow-Up Top

Long-term follow-up as in patients with stable angina (see Stable Angina Pectoris).

Secondary Prevention Top

1. Control of risk factors of atherosclerosis (see Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases).

2. Regular exercise: ≥30 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise (the intensity is determined on the basis of the stress test) ≥5 times a week or supervised rehabilitation programs in high-risk patients.

3. Pharmacotherapy (specific indications: Table 6): Antiplatelet agents (ASA and/or clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor), beta-blockers, ACEIs (or ARBs), statins, aldosterone antagonists, as indicated.

4. Anticoagulant treatment is recommended after coronary stenting in patients with atrial fibrillation and a moderate to high risk of thromboembolic complications (CHADS2 score ≥1). Treatment with a direct oral anticoagulant [DOAC]) is indicated according to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society antiplatelet guidelines. The role and duration of dual and triple therapies are discussed in the NSTEMI chapter (see Non–ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI) and Unstable Angina (UA)).

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Agent and dosage |

Indications |

|

ASA 70-100 mg/d |

Lifelong in all patients unless contraindicated |

|

Clopidogrel 75 mg once daily or Ticagrelor 90 mg bid or Prasugrel 10 mg once daily |

– Lifelong in patients with ASA contraindications or intolerance – Combined with ASA for 12 months after ACS

– Combined with ASA for 12 months after ACS

– Combined with ASA for 12 months after ACS |

|

Beta-blocker |

– All patients after UA/NSTEMI with LV dysfunction unless contraindicated – All patients after STEMI unless contraindicated |

|

ACEI |

– Patients after UA/NSTEMI with heart failure, LV dysfunction (LVEF <40%), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or chronic kidney disease. Consider in all other patients as prevention of further ischemic events – All patients after STEMI |

|

Statin |

All patients (unless contraindicated) regardless of baseline cholesterol levels. Target LDL-C <1.8 mmol/L or 70 mg/dL (<1.4 mmol/L [55 mg/dL] according to ESC guidelines) |

|

ARB |

All patients who do not tolerate ACEI, and particularly those with heart failure and LV dysfunction (LVEF <40%) |

|

MRA |

Patients after MI treated with beta-blockers and ACEI with LVEF <40% and with diabetes mellitus or heart failure but without significant renal dysfunction or hyperkalemia |

|

Based on Eur Heart J. 2016;37(3):267-315 and Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119-177. | |

|

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; bid, 2 times a day; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NSTEMI, non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina. | |

|

ECG leads |

Location of MI |

|

V1-V4 |

LV anterior wall, ventricular septum, apex |

|

I, aVL, V5-V6 |

LV lateral wall, apex |

|

II, III, aVF |

LV inferior wall |

|

V1-V3 (tall R waves), |

LV posterior wall |

|

V4R-V6R (ST-segment elevation ≥0.05 mV)b |

Right ventricle |

|

a ≥0.1 mV in male patients aged <40 years. b ≥0.1 mV in male patients aged <30 years. In 50%-70% of cases of inferior wall ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, so-called mirror ST-segment depressions are found in the anterior or lateral leads; this is also true for 40%-60% of anterior wall MIs with mirror elevation in the inferior leads. This finding is associated with more extensive infarction and a worse prognosis. ST-segment depression in anterior leads may also represent posterior MI. | |

|

ECG, electrocardiography; LV, left ventricle; MI, myocardial infarction. | |

|

Fibrinolytic agent |

Dosage |

Anticoagulant therapya |

|

tPA |

IV bolus 15 mg, then 0.75 mg/kg over 30 min, then 0.5 mg/kg over 60 min (up to a total of ≤100 mg) |

UFH: 60 IU/kg in IV bolus (up to 4000 IU), then 12 IU/kg/h in IV infusion (up to 1000 IU/h) for 24-48 hours. Target aPTT, 50-70 s; check aPTT after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h Enoxaparin: – Patients <75 years: 30 mg IV bolus, then after 15 min 1 mg/kg SC every 12 h. The 2 initial SC doses should be ≤100 mg – Patients >75 years: No IV bolus; start with 0.75 mg/kg SC every 12 h. The 2 initial SC doses should be ≤75 mg – Patients with creatinine clearance <30 mL/min, regardless of age: SC injections every 24 h Fondaparinux: 2.5 mg IV, then 2.5 mg SC every 24 h |

|

TNK tPA |

Single IV injection at a dose based on body weight: <60 kg: 30 mg ≥60 to <70 kg: 35 mg ≥70 to <80 kg: 40 mg ≥80 to <90 kg: 45 mg ≥90 kg: 50 mg | |

|

SK |

1.5 million IU in 100 mL of 5% glucose (dextrose) or 0.9% saline, IV infusion over 30-60 min |

Fondaparinux: 2.5 mg SC, then 2.5 mg/d SC every 24 h |

|

a Administer until discharge but no longer than for 8 days. In patients with severe renal failure (creatinine clearance <20 mL/min) use unfractionated heparin rather than other anticoagulants. | ||

|

aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous; SK, streptokinase; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TNK tPA, tenecteplase; tPA, alteplase; UFH, unfractionated heparin. | ||

|

Risk factor |

Score | |

|

Age |

Individual risk factors receive varying numbers of points. Total points correspond to odds of death at 30 days | |

|

Diabetes mellitus/hypertension or angina | ||

|

Systolic blood pressure | ||

|

Heart rate | ||

|

Killip class II-IV | ||

|

Weight | ||

|

Anterior ST-elevation or left bundle branch block | ||

|

Time to treatment | ||

|

Original data and tool can be found in Circulation. 2000;102(17):2031-7. | ||

|

STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction. | ||

|

Killip class | |

|

Killip class II |

4 |

|

Killip class III |

9 |

|

Killip class IV |

9 |

|

TIMI flow | |

|

TIMI flow 0 |

2 |

|

TIMI flow 1 |

2 |

|

TIMI flow 2 |

1 |

|

Age | |

|

Age ≥60 years |

2 |

|

3-vessel disease | |

|

3-vessel disease present |

1 |

|

Myocardial infarction | |

|

History of anterior myocardial infarction |

1 |

|

Ischemia time | |

|

Ischemia time >4 h |

1 |

|

Total score | |

|

Based on Circulation. 2004;109(22):2737-43. | |

|

STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction. | |

Figure 3.11-3. Management algorithm for patients with acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation presenting within 24 hours of the first medical contact. Based on Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119-177 and Eur Heart J. 2019;40(2):87-165.

Figure 3.11-1. A 76-year-old patient hospitalized in the second hour of pain: A, electrocardiography (ECG) on admission (paper speed, 50 mm/s); B, coronary angiography: total occlusion of the right coronary artery before percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); C, post-PCI coronary angiography: right coronary artery (TIMI grade 3 flow).

Figure 3.11-2. A 53-year-old patient hospitalized in the second hour of pain: A, electrocardiography (ECG) on admission (paper speed, 50 mm/s); B, coronary angiography: total occlusion of the left anterior descending artery (arrow); C, coronary angiography: left anterior descending artery after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (TIMI grade 3 flow).