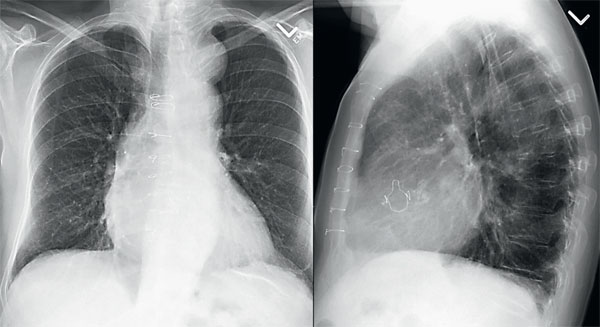

70-year-old male patient presented with upper chest pain he’d been experiencing for six months. He had a history of cardiac disease. There was no history of trauma and the patient was afebrile (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Posteroanterior (PA) and lateral chest radiographs were requested

Part 1. Chest Radiographs

Question

1. Do you see any abnormalities on the radiograph?

2. How do you describe the principle abnormality?

3. Where is the precise location of the abnormality?

Answers and explanation

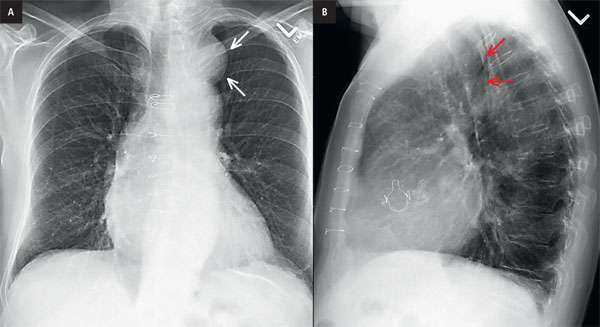

The most apparent finding on the PA image is the presence of homogeneous opacity in the superior mediastinal, with its inferior margin indistinct from the aortic knuckle. The superior margin is projected over the medial end of the left clavicle. Laterally the margin is well outlined against the underlying air in left lung (arrow on AP radiograph). The medial margin of the opacity is obscured (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Posteroanterior (PA) and lateral chest radiographs were requested with arrows. Sternotomy wires and aortic replacement valve are seen, consistent with patients known condition of cardiac disease.

Pearls

The silhouette sign is based on the premise that an intrathoracic radiopacity, if in anatomic contact with a border of the heart or aorta, will obscure that border. The medial border of the mass is silhouetting the superior mediastinum.

The cervicothoracic sign is based on the tenet that if a thoracic lesion is in anatomic contact with the soft tissues

of the neck, its contiguous border will be lost. The cephalic border of the anterior mediastinum ends at the level

of the clavicles, whereas that of the posterior mediastinum extends much higher. Hence, a lesion clearly visible above

the clavicles on the frontal view must lie posteriorly and be entirely within the thorax, as was the situation in our case.

Esophageal masses, vascular anomalies such as an aberrant subclavian artery, double aortic arch, or aneurysm,

and mediastinal extension from a thyroid goitre can all cause increased opacity in the retro

tracheal triangle (arrow on lateral radiograph).

Anatomy of middle mediastinum

The heart and pericardium are in the middle mediastinum, along with the ascending and transverse aorta, the superior vena cava and the azygos vein that empties into it, the phrenic nerves, the upper vagus nerves, the trachea and its two branches, the main bronchi, the pulmonary artery and its two branches, the pulmonary veins, and the lymph nodes next to them. The oesophagus may be referred to as a middle or posterior mediastinal structure.

Top Differential Diagnoses

Based on the above explanation our mass is in the middle mediastinum.

| Approach the differentials with a chest radiograph? | |

|---|---|

| Anterior mediastinal masses |

Middle mediastinum |

| Common: Thymoma, thyroid tumour, teratoma, and dreadful lymphoma. |

Common: adenopathy, aneurysms and other vascular problems, and developmental problems. |

| Less frequent causes of an anterior mediastinal mass include vascular tortuosity or aneurysm, cardiac tumours or prominent pericardiac fat, cystic hygroma, bronchogenic cyst, pericardial cyst, hemangioma, lymphangioma, parathyroid adenoma, various other mesenchymal tumours (e.g., fibroma or lipoma), sternal tumour, primary lung. |

Giant lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman disease), neural tumour (involving the vagus or phrenic nerve), abscess, fibrosing mediastinitis, hiatal hernia, primary tumours of the trachea or oesophagus (such as leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, or carcinoma), and hematoma are some of the less common middle mediastinal abnormalities. |

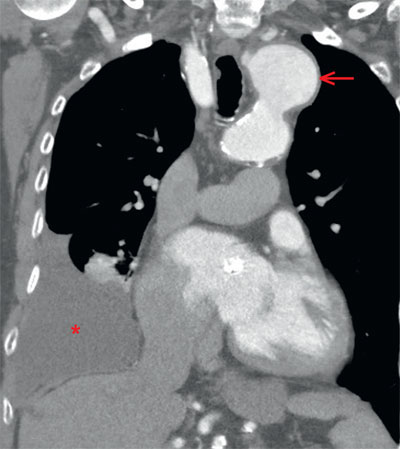

Part 2. CT scan

This case was subsequently investigated with a CT scan of the chest.

Figure 3. Coronal reformatted images of a contrast CT chest demonstrates a large aneurysm (arrow) from the arch of aorta, without any imaging findings of dissection. A moderate volume of simple appearing pleural effusion (star) is seen on the right side with compressive atelectasis of the basilar right lower segments.

Summary

- The aorta, being a structure of the middle mediastinum, can potentially cause problems in this compartment. With advancing age, the aorta frequently becomes atherosclerotic and ectatic, and it might become aneurysmal.

- Aortic aneurysm's most dreaded complication its rupture.

- Cystic medial necrosis, connective tissue disorders such as Marfan and Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, and syphilis are the most common causes of ascending aortic aneurysms (now rare). Atherosclerotic, posttraumatic, infectious (mycotic), or inflammatory aneurysms of the descending aorta are the most common (rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis).

- Most atherosclerotic aneurysms are fusiform, but others are saccular. Fusiform aneurysms typically originate from the aortic arch or the descending thoracic aorta. Saccular aneurysms of the ascending aorta are uncommon. Saccular aneurysms often develop in the descending aorta or sometimes in the aortic arch.

- Mycotic aneurysms of the aorta occur in patients with predisposing conditions, including intravenous drug abusers, patients with valvular disease or congenital disorders of the heart or aorta, patients who have undergone previous cardiac or aortic surgery, patients with adjacent pyogenic infection, and immunocompromised individuals. Mycotic aneurysms are often sac-shaped, rapidly growing, and without calcification of the wall.

- Aneurysms can be classified as true (having an intact aorta wall composed of intima, media, and adventitia) or false in terms of aortic wall integrity (also called pseudoaneurysm, characterized by a disrupted aortic wall contained by the adventitia, perivascular connective tissue, and organized blood clot). True aneurysms are those caused by atherosclerosis or connective tissue disorders. Posttraumatic and infectious (mycotic) aneurysms are frequently false.

Teaching points

- A thoracic aortic aneurysm is defined as an aorta diameter higher than 4 cm and is characterized according to location, morphology, aortic wall integrity, and etiology.

- Aortic aneurysms are distinguishable from other mediastinal masses by their conformance to the aorta and the prevalence of curvilinear calcification in the aneurysm wall.

- It is crucial to differentiate an aortic aneurysm from other mediastinal masses, especially when a biopsy is being considered.

- Fusiform aneurysms are those that expand the entire aortic circumference, while saccular aneurysms are more delineated and usually involve a specific portion of the aorta, which often appears as an eccentric outpouching.

- Consider ruptured aneurysm: Acute chest pain, wide mediastinum, and pleural effusion on radiography.

- Normal radiography does not exclude aneurysm or dissection, cross-sectional imaging is needed for diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Aneurysm from arch of aorta

You can find more interesting cases in the app "Discover Radiology: Chest x-ray interpretation".

Price – only $6.99

References

1. Goodman L.R.: Felson's principles of chest roentgenology, a programmed text. Elsevier Health Sciences, 20142. DeBakey M.E., Henly W.S., Cooley D.A. i wsp.: Surgical management of dissecting aneurysms of the aorta. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg., 1965; 49: 130–149

3. Posniak H.V., Olson M.C., Demos T.C. i wsp.: CT of thoracic aortic aneurysms. Radiographics, 1990; 10: 839–855