Satia I, Wahab M, Kum E, et al. Chronic cough: Investigations, management, current and future treatments. Canadian Journal of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine. 2021 Sep 23:1-3. doi: 10.1080/24745332.2021.1979904.

Morice AH, Millqvist E, Bieksiene K, et al. ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. Eur Respir J. 2019 Sep 12. pii: 1901136. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01136-2019. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 31515408.

Gibson P, Wang G, McGarvey L, Vertigan AE, Altman KW, Birring SS; CHEST Expert Cough Panel. Treatment of Unexplained Chronic Cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016 Jan;149(1):27-44. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1496. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PMID: 26426314; PMCID: PMC5831652.

DefinitionTop

Cough is the most common symptom for which patients seek medical attention. It is a protective reflex that clears the airways of excess secretions, foreign bodies, and noxious and harmful environmental irritants. Cough consists of a deep inspiration followed by expiration with an initial brief glottic closure. The high pressure generated in the chest and lungs results in a forceful expulsion of air after the opening of the glottis, which drives particles out of the airway. In most cases coughing can occur appropriately as an automatic defensive reflex, but in ~12% of the general population chronic cough can become a persistent troublesome symptom lasting >8 weeks. In such cases coughing can be triggered by trivial exposure to irritants such as perfumes, aerosols, or changes in temperature, but also by talking, laughing, or singing. This clinical presentation has been recently termed “cough hypersensitivity syndrome” and reflects an underlying hypersensitivity of the peripheral airway nerves or central nervous system (or both).

Causes and PathogenesisTop

1. Classification based on duration of cough:

1) Acute cough: Persists for <3 weeks. The causes are most frequently infection (usually viral upper respiratory tract infection) and bronchitis, or less frequently aspiration, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary edema, or pneumonia. Acute cough may be a physiological response to a foreign body in the airways as well as to irritant dust or noxious chemicals.

2) Subacute cough: Persists for 3 to 8 weeks. Most frequently caused by viral infections and occasionally by whooping cough.

3) Chronic cough: Persists for >8 weeks, peaks in patients in their 50s and 60s, and is twice as common in women compared with men. Causes: Table 1.

2. Classification based on characteristics of cough:

1) Nonproductive (so-called dry) cough may be caused by viral infections, asthma, interstitial lung disease, and smoking. It may occur with use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) (cough affects up to 14% of patients treated with this class of drugs; mechanism is currently unclear; cough can often occur after a long latency and can continue for many months after drug discontinuation).

2) Productive cough leading to expectoration of sputum. Characteristics and possible causes of expectorated sputum:

a) Purulent sputum (green or yellow): Bronchiectasis, primary ciliary dyskinesia, sinusitis, chronic bronchitis, pneumonia, tuberculosis.

b) Copious purulent sputum: Bronchiectasis. A sudden-onset production of copious purulent sputum may indicate rupture of a lung abscess into a bronchus.

c) Foul-smelling sputum: Usually present in anaerobic infection. Consider abscess and food aspiration.

d) Mucous, thick, viscous sputum occurring most frequently in the morning: Chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma.

e) Clear, viscous sputum: Asthma, rarely adenocarcinoma.

f) Sputum with aggregates and plugs: Fungal infection, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, cystic fibrosis, rarely plastic bronchitis.

g) Sputum with food particles: Tracheoesophageal fistula, dysphagia with aspiration.

h) Bloody sputum (hemoptysis): Consider malignancy, tuberculosis, pulmonary embolus, vasculitis, rarely arteriovenous malformations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome).

3. Causes of ineffective cough: Weakness of the respiratory or abdominal muscles secondary to neurologic impairment (peripheral and central causes) or muscle weakness (Pompe disease), impaired chest mobility, increased mucus viscosity, ciliary dysfunction.

4. Complications of cough: Syncope (more common in men), secondary spontaneous pneumothorax, rib fractures (usually pathologic fractures, eg, due to tumor metastasis), injury to the intercostal muscles or nerves resulting in musculoskeletal pain, urinary incontinence, depression, and anxiety.

DiagnosisTop

1. History and physical examination: Investigate the character of cough, triggering and relieving factors, and accompanying symptoms to establish the diagnosis (Table 1).

2. Diagnostic tests:

1) Acute and subacute cough, if not accompanied by symptoms causing concern (dyspnea, hemoptysis, persistent weight loss or fever, night sweats, loss of consciousness), is usually caused by viral infection and does not require further evaluation. In patients with symptoms raising suspicion of an alternative disease, perform chest radiography, assess blood oxygenation (pulse oximetry, blood gas analysis), and, depending on suspected cause, perform cardiovascular (electrocardiography [ECG], echocardiogram) or respiratory (chest x-ray [CXR] or computed tomography [CT], bronchoscopy, pulmonary function tests) diagnostics. In patients with productive cough, perform microbiologic examination of sputum including mycology and mycobacteria.

2) Chronic cough: Start with chest radiography (consider high-resolution chest CT with inspiratory/expiratory and prone/supine views only if there is any clinical evidence of malignancy, tuberculosis, interstitial lung diseases, or small airways diseases), pulmonary function tests (postbronchodilator spirometry with reversibility assessment), and ear, nose, and throat (ENT) examination (for the diagnosis of muscle tension dysphonia [MTD] and inducible laryngeal obstruction [ILO]). In patients with productive cough, perform microbiologic and cytologic examination of the sputum. Perform bronchoscopy as deemed necessary, particularly in patients with a suspicion of cancer, presence of a foreign body, or tracheobronchomalacia. In some patients exhaled nitric oxide, sputum induction, and bronchial challenge testing can be considered to investigate for eosinophilic bronchitis and asthma. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and esophageal pH-impedance manometry may be necessary to objectively assess for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

3) Indications for urgent diagnostic workup: Hemoptysis, recent cough or a change in the nature of the cough in a tobacco smoker, dyspnea, hoarseness, fever, weight loss, peripheral edema, swallowing disorders, vomiting, recurrent pneumonia, abnormal functional respiratory test results, or a newly abnormal chest radiograph (coinciding with the onset of cough).

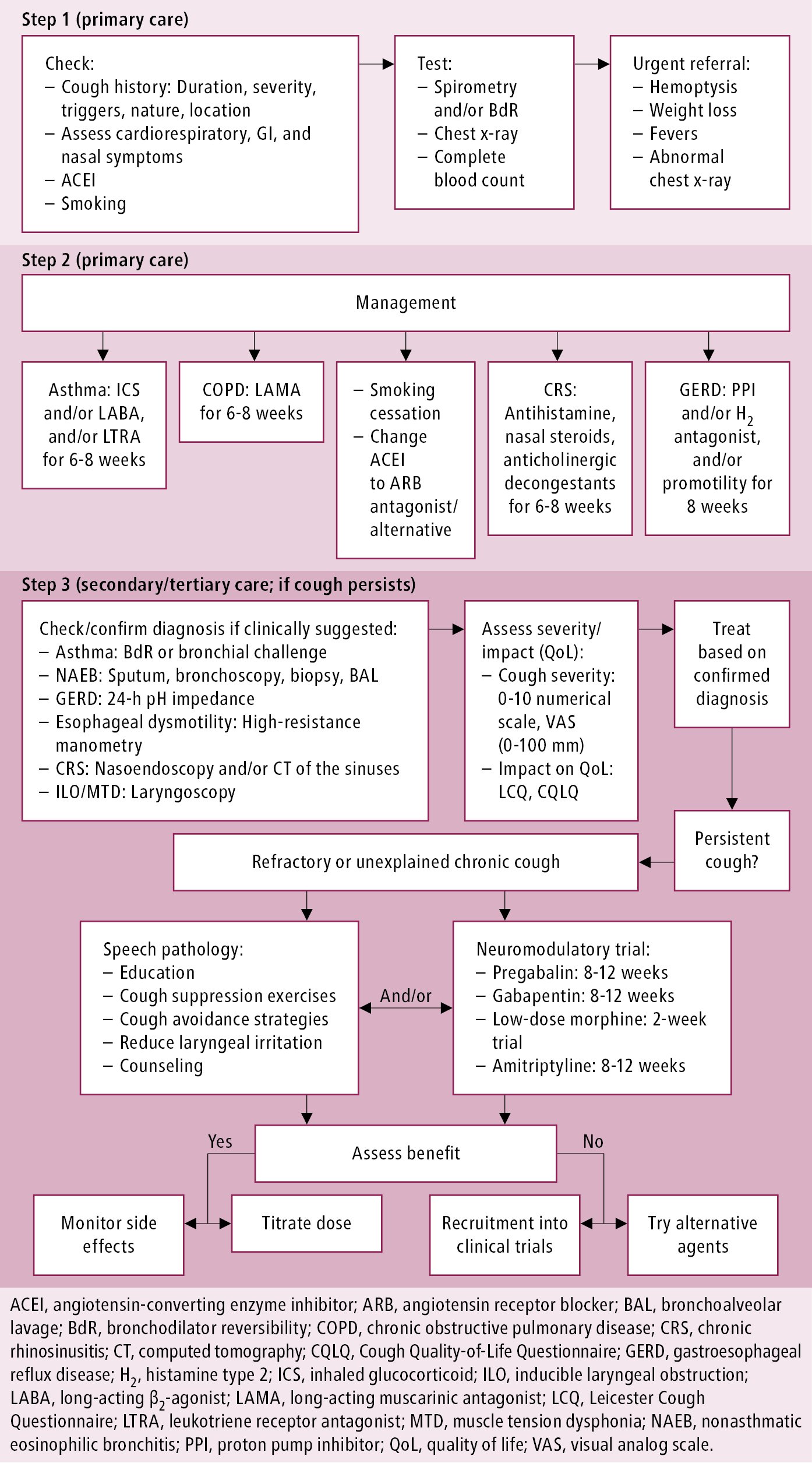

Algorithm for diagnosis and management: Figure 1.

TreatmentTop

Symptomatic Treatment of Productive Cough

In patients with a productive cough secondary to excessive mucus leading to airway plugging and recurrent infections, it is suggested to use the following measures that facilitate the evacuation of airway secretions and increase the effectiveness of cough: respiratory physiotherapy (postural drainage, chest percussion and vibration, educating the patient how to cough effectively), nebulized hypertonic saline (5%-7% NaCl with pretreatment with a bronchodilator to prevent bronchoconstriction), airway suctioning using a suction catheter (in intubated patients) or a flexible bronchoscope (particularly if secretions lead to atelectasis). Mucolytic agents (acetylcysteine, ambroxol, bromhexine, carbocysteine [INN carbocisteine], ammonium chloride, guaifenesin) are less useful. We suggest a trial of a low-dose macrolide antibiotic (azithromycin 250 mg daily or 3 times/wk) for 6 to 12 months in patients with bronchiectasis and recurrent infective exacerbation.Evidence 1Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the small sample size (imprecision) and incomplete clinically relevant outcomes. Wong C, Jayaram L, Karalus N, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (EMBRACE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012 Aug 18;380(9842):660-7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60953-2. PMID: 22901887. Altenburg J, de Graaff CS, Stienstra Y, et al. Effect of azithromycin maintenance treatment on infectious exacerbations among patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: the BAT randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013 Mar 27;309(12):1251-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1937. PMID: 23532241. Serisier DJ, Martin ML, McGuckin MA, et al. Effect of long-term, low-dose erythromycin on pulmonary exacerbations among patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: the BLESS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013 Mar 27;309(12):1260-7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2290. PMID: 23532242. However, care should be taken to exclude nontuberculous mycobacteria and ensure monitoring of cardiac arrhythmias (long QTc), hearing loss, and gastrointestinal adverse effects (diarrhea). In exceptional cases, in patients receiving palliative care who are too weak to expectorate effectively, drugs that decrease the production of airway secretions (eg, subcutaneous hyoscine [dose for scopolamine butylbromide] 20-40 mg/d) may be combined with cough suppressants.

Symptomatic Treatment of Dry Cough

There are currently no medications licensed or approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or European Medicines Agency for the treatment of chronic cough. However, if treatment of any of the underlying conditions, such as asthma, GERD, and postnasal drip, is ineffective, management algorithms can consider the following treatment options:

1) Centrally acting cough suppressants: The vast majority of over-the-counter cough syrups contain dextromethorphan, which is used in doses of 60 to 120 mg/d, but this has very little evidence for clinical efficacy. It is acknowledged that swallowing syrups and honey and sucking lozenges may provide a soothing and demulcent effect in the case of transient throat irritation. Among opioids, oral morphine sulfate (modified release), usually at a low dose of 5 mg every 12 hours and increasing to a maximum of 10 mg, is a common medication used in most tertiary specialist cough clinics.Evidence 2Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision (small number of patients) and indirectness (tertiary care). Morice AH, Menon MS, Mulrennan SA, et al. Opiate therapy in chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Feb 15;175(4):312-5. Epub 2006 Nov 22. PMID: 17122382. Badri H, Satia I, Woodcock A, Smith JA. The use of low dose morphine for the management of chronic cough in a tertiary cough clinic. Presented at the American Thoracic Society 2015 International Conference. http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2015.191.1_MeetingAbstracts.A4117. Abstract. No comparable evidence exists for the use of codeine in chronic cough. Gabapentin and the related medication pregabalin (with or without speech and language therapy) have been evaluated in studies with improvement in cough but their doses need to be carefully titrated up to prevent adverse effects, such as hallucinations, dizziness, and unsteadiness.Evidence 3Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the short duration of study and relatively few involved patients. Ryan NM, Birring SS, Gibson PG. Gabapentin for refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012 Nov 3;380(9853):1583-9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60776-4. Epub 2012 Aug 28. PMID: 22951084. In selected patients with chronic cough presumed to be related to a previous viral infection, amitriptyline 10 mg at night has been shown to be superior to codeine plus guaifenesin in an open-label uncontrolled study.Evidence 4Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the small number of involved patients and indirectness (very specific population included [post-viral vagal neuropathy]). Jeyakumar A, Brickman TM, Haben M. Effectiveness of amitriptyline versus cough suppressants in the treatment of chronic cough resulting from postviral vagal neuropathy. Laryngoscope. 2006 Dec;116(12):2108-12. PMID: 17146380.

2) Antacid therapy: Systematic reviews found no consistent benefit over placebo to support the routine use of proton pump inhibitors, but the benefit is most likely in those with high esophageal acid exposure and objective evidence of high frequency of reflux episodes.Evidence 5Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias and heterogeneity. Chang AB, Lasserson TJ, Gaffney J, Connor FL, Garske LA. Gastro-oesophageal reflux treatment for prolonged non-specific cough in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jan 19;(1):CD004823. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004823.pub4. Review. PMID: 21249664. Kahrilas PJ, Howden CW, Hughes N, Molloy-Bland M. Response of chronic cough to acid-suppressive therapy in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Chest. 2013 Mar;143(3):605-612. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1788. Review. PMID: 23117307; PMCID: PMC3590881.

3) Speech and language therapy: Recent studies have recognized beneficial outcomes of cough-specific therapy aimed towards education, reduction of laryngeal irritation, cough-control techniques, and psychoeducational counseling.Evidence 6Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision (low number of patients) and indirectness (short trial duration). Slinger C, Mehdi SB, Milan SJ, et al; Cochrane Airways Group. Speech and language therapy for management of chronic cough. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jul; 2019(7): CD013067. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013067.pub2. PMCID: PMC6649889; PMID: 31335963. Chamberlain Mitchell SA, Garrod R, Clark L, et al. Physiotherapy, and speech and language therapy intervention for patients with refractory chronic cough: a multicentre randomised control trial. Thorax. 2017 Feb;72(2):129-136. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208843. Epub 2016 Sep 28. PMID: 27682331. Birring SS, Floyd S, Reilly CC, Cho PSP. Physiotherapy and Speech and Language therapy intervention for chronic cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2017 Apr 4. pii: S1094-5539(17)30011-1. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.04.001. [Epub ahead of print] Review. PMID: 28389257. Such techniques have also shown to be more effective in combination with pregabalin.Evidence 7Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the relatively small number of involved patients and short durations of trials. Vertigan AE, Theodoros DG, Gibson PG, Winkworth AL. Efficacy of speech pathology management for chronic cough: a randomised placebo controlled trial of treatment efficacy. Thorax. 2006 Dec;61(12):1065-9. Epub 2006 Jul 14. PMID: 16844725; PMCID: PMC2117063. Vertigan AE, Kapela SL, Ryan NM, Birring SS, McElduff P, Gibson PG. Pregabalin and Speech Pathology Combination Therapy for Refractory Chronic Cough: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Chest. 2016 Mar;149(3):639-48. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1271. Epub 2016 Jan 12. PMID: 26447687.

4) Local anesthetics (lidocaine or bupivacaine aerosols) are used mainly for short-term suppression of the cough reflex before bronchoscopy or airway suctioning. There is limited evidence showing short-term reduction in cough frequency with lidocaine throat spray in patients with refractory chronic cough.Evidence 8Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the small number of involved patients and indirectness. Abdulqawi R, Satia I, Kanemitsu Y, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess the Effect of Lidocaine Administered via Throat Spray and Nebulization in Patients with Refractory Chronic Cough. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021 Apr 1;9(4):1640-1647. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.037. PMID: 33259976.

5) Treatment for cancer-related cough: In patients with cough caused by airway edema, compression by tumors, lymphangitis, or pneumonitis following radiotherapy or chemotherapy, consider a trial course of glucocorticoids (usually dexamethasone 4 mg bid) for 2 to 4 weeks. In other scenarios consider levodropropizine 60 mg up to tid at intervals ≥6 hours. Aprepitant 125 mg 1 hour before chemotherapy then 80 mg daily as a single dose for the next 2 days has been evaluated mainly in patients with cancer. Inhaled sodium cromoglycate 40 microg/d can be tried. Use centrally-acting cough suppressants only if treatment with glucocorticoids is inappropriate or ineffective.

Future Treatment for Chronic Cough

While acute and subacute cough are usually self-limiting or can be treated with antibiotics when needed, investigations and treatment in patients with chronic cough can be difficult. Our understanding of the peripheral and central mechanisms causing chronic cough have vastly improved over the last 2 decades, and this has most recently led to the development of oral treatments, such as gefapixant and eliapixant, targeting the purinergic ion channel P2X3, which is activated by adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Blocking this channel has led to an unprecedented reduction in objective cough frequency and improved quality of life in patients with chronic cough in early studies.Evidence 9Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the small number of patients. Abdulqawi R, Dockry R, Holt K, et al. P2X3 receptor antagonist (AF-219) in refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2015 Mar 28;385(9974):1198-205. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61255-1. Epub 2014 Nov 25. PMID: 25467586. Smith JA, Kitt MM, Butera P, et al. Gefapixant in two randomised dose-escalation studies in chronic cough. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(3):1901615. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01615-2019. PMID: 31949115. Smith JA, Kitt MM, Morice AH, et al; Protocol 012 Investigators. Gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist, for the treatment of refractory or unexplained chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, controlled, parallel-group, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(8):775-785. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30471-0. PMID: 32109425. Morice A, Smith JA, McGarvey L, et al. Eliapixant (BAY 1817080), a P2X3 receptor antagonist, in refractory chronic cough: a randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover phase 2a study. Eur Respir J. 2021 Nov 18;58(5):2004240. doi: 10.1183/13993003.04240-2020. PMID: 33986030; PMCID: PMC8607926. The results of more definitive studies are currently (December 2021) under regulatory review. It is hoped that in the coming years this new class of treatment targeting the purinergic receptor will be made available to patients.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Cause |

Accompanying signs and symptoms, cough characteristics, sputum production |

|

Asthma or (much less often) eosinophilic bronchitis |

Attack of cough may be triggered by exposure to specific or nonspecific factors, such as allergens, cold air, exercise; cough often occurring at night; accompanied by dyspnea and wheezing; good response to bronchodilators and inhaled glucocorticoids; mucous sputum, may be yellowish (high eosinophil content) |

|

Gastroesophageal reflux |

Most often accompanied by heartburn and other dyspeptic symptoms, but GI symptoms may be absent; sometimes accompanied by hoarseness or dysphonia; improved by PPI and H2 antagonist treatment (2-month treatment recommended) |

|

Postnasal drip |

Chronic rhinitis with postnasal drip; often history of allergy; concomitant chronic sinusitis; most frequently mucous sputum; “cobblestone” pattern of posterior pharyngeal mucosa |

|

Chronic bronchitis or COPD |

History of smoking and frequent respiratory tract infections; most severe in the morning and immediately after waking up; often resolves on expectoration of mucous secretions |

|

Bronchiectasis |

Copious amounts of expectorated sputum (especially in the morning), often purulent, yellow and green |

|

ACEI |

Dry cough resolving after drug discontinuation, although in some cases may persist for several months |

|

Pneumonia, lung abscess, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, tumors |

Manifestations of underlying condition depending on its severity |

|

Left ventricular failure, mitral stenosis, aortic aneurysm compressing trachea or bronchi |

Usually attacks of dry cough at night; may be accompanied by wheezing; pink frothy secretions in patients with pulmonary edema; considerably enlarged left atrium or dilated pulmonary artery may compress recurrent laryngeal nerve and cause hoarseness |

|

Chronic idiopathic cough |

No cause identified but attributed to cough hypersensitivity syndrome; commonly triggered by strong smells, perfumes, aerosols, change in temperature, talking, laughing, and singing; symptoms of irritation of throat and chest |

|

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GI, gastrointestinal; PPI, proton pump inhibitor. | |

Figure 1.5-1. Stepwise approach to the diagnosis and management of chronic cough in primary and secondary care. Adapted from Canadian Journal of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine. 2021 Sep 23:1-3.