Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza (Flu). Reviewed June 5, 2024. Accessed September 8, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm

Government of Canada. Avian influenza A(H5N1): For health professionals. Updated July 26, 2024. Accessed September 8, 2024. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/avian-influenza-h5n1/health-professionals.html

DEFINITION, ETIOLOGY, PATHOGENESISTop

Influenza is an acute respiratory illness caused by influenza viruses. Seasonal influenza outbreaks occur annually and are caused by seasonal human influenza virus strains types A and B. Pandemic influenza occurs every several years to decades and is caused by novel reassortant strains of influenza A to which humans have not been previously exposed, for instance, the Spanish influenza pandemic in the 1920s. Pandemic influenza by definition implies global spread, and the incidence of infection is typically several-fold higher than during seasonal influenza epidemics. An influenza pandemic is declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) on the basis of widespread geographic distribution of infections with a new virus strain, regardless of the severity of the disease.

1. Etiologic agent: Epidemic outbreaks in humans are caused by influenza virus types A or B. Influenza A virus is divided into subtypes defined on the basis of antigenic specificity of 2 surface proteins: hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). Seasonal influenza epidemics are most frequently caused by the H1N1 and H3N2 subtypes of influenza A virus, with a lower frequency of circulation of influenza B virus (~20%). Influenza A virus is characterized by a high antigenic variation that is associated with a relative lack of protective immunity in subsequent seasons and therefore warrants an annual update of immunization against influenza H1N1 and H3N2 strains. Influenza B viruses are separated into 2 distinct genetic lineages (Yamagata and Victoria). Because they undergo antigenic drift less rapidly than influenza A viruses, they are not categorized into subtypes. Influenza B viruses from both lineages previously cocirculated, but frequently one lineage predominated. However, over the course of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, circulation of the influenza B lineage Yamagata disappeared, such that in September 2023 and February 2024 the WHO influenza vaccine composition advisory committee advised that the B/Yamagata lineage antigen no longer needed to be included in quadrivalent influenza vaccines. In the Northern hemisphere the influenza season typically extends from fall to early spring (October to April). Sporadic human infections with avian influenza viruses (potentially pandemic subtypes) associated with high morbidity and mortality rates have been reported predominantly in Asia, Egypt (H5N1), and most recently in China (H7N9, H10N8). However, so far there has been no evidence of ongoing sustained person-to-person spread of these avian influenza virus subtypes. In June 2009, the WHO declared a pandemic caused by a new influenza H1N1 2009 subtype, which dominated the 2009/2010 influenza season, almost entirely displacing the prior seasonal subtypes. It should be noted that avian influenza A (H5N1) in domestic and wild mammals has become widespread in many parts of the world, including Canada, the United States, and Europe. Human cases have occurred through close contact with infected birds, and human-to-human transmission is rare. The clinical presentation typically includes respiratory symptoms, although gastrointestinal issues and encephalopathy can also occur. Clinical cases are predominantly seen in children and young adults. Public health officials continue to monitor this situation closely.

2. Pathomechanism: Influenza virus replicates in the epithelium of the upper and lower respiratory tract and rarely causes viremia; the systemic signs and symptoms of the infection are caused by cytokines released due to inflammatory response.

3. Reservoirs and transmission: The reservoirs of influenza viruses are humans and certain animals (eg, pigs, dogs, cats, horses, domesticated and wild birds). Transmission is by droplets of human secretions (although transmission by direct contact with virus-contaminated surfaces is also possible). In avian influenza the reservoirs are infected birds; transmission to humans may be via direct close contact with a sick person or through a close contact with infected birds.

4. Incubation period: One to 7 days (2 days on average). In adults, the virus shedding lasts from 1 day prior to the onset of symptoms to 3 to 5 days after the onset of symptoms (in some cases up to 10 days). Young children may shed the virus from a few days before to ≥10 days after the onset of symptoms. Severely immunocompromised patients may shed the virus for several weeks or months.

5. Risk factors for infection:

1) Prolonged close contact (within 1.5-2 meters) with a sick individual without a protective barrier (face mask) or direct face-to-face contact without protective measures.

2) Direct contact with a sick or infected individual, or with objects contaminated by influenza virus.

3) Inadequate hand hygiene.

4) Touching mouth, nose, or eyes with contaminated hands.

5) Staying in crowded spaces, especially if enclosed, during the influenza season.

CLINICAL FEATURESTop

The disease onset in healthy hosts is typically rapid and includes the following:

1) Systemic signs and symptoms: Fever, chills, myalgia, headache (most commonly frontal and retro-orbital), fatigue, and malaise.

2) Respiratory symptoms: Usually delayed by a few days; may include sore throat, rhinitis (usually mild), and dry cough.

3) Less common symptoms: Nausea, vomiting, and/or mild diarrhea (particularly in children). Usually the patients recover spontaneously within 3 to 7 days; cough and malaise may persist for ≥2 weeks. Up to 50% of cases are asymptomatic.

In the elderly, the presentation is frequently more subtle and may include fever, malaise, cough, or sore throat alone.

The disease usually resolves spontaneously after 3 to 7 days, but cough and discomfort may persist for ≥2 weeks. Up to 50% of infections are asymptomatic.

DIAGNOSISTop

1. Virology: Detection of the genetic material of the virus (reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR]), immunofluorescence assays (direct [DFA] or indirect [IFA] fluorescence antibody staining), isolation of the virus using cell cultures and rapid influenza antigen detection tests (rapid influenza diagnostic test [RIDT]) on nasal and pharyngeal specimens (aspirate, wash, swab; the nose and throat samples should be pooled). Typically, virology testing is done early in the season when there is uncertainty about influenza, but usually it is not necessary during the peak influenza season. However, it should be considered in patients with risk factors for complications or severe course of influenza (see below), or in cases of severe (complicated) and progressive influenza-like illness (ILI) or any other indication for hospitalization (see below). Results of the testing may be useful in determining whether the infecting strain is resistant to treatment. The test with the highest diagnostic accuracy is RT-PCR. Respiratory samples should be collected as early as possible after the onset of symptoms (ideally within 48-72 h) to maximize influenza testing sensitivity. Any errors related to the type of samples, time and method of sampling, and storage and transport conditions may cause false-negative results. If the clinical suspicion is high, consider repeating the test if negative. In the case of lower respiratory tract infections, testing tracheal and bronchial aspirates has superior diagnostic value. RIDTs are highly specific, with pooled specificity of 98%, but moderately sensitive, with pooled sensitivity of 62%Evidence 1Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to methodology issues (lack of blind assessment) and indirectness to new tests. Chartrand C, Leeflang MM, Minion J, Brewer T, Pai M. Accuracy of rapid influenza diagnostic tests: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Apr 3;156(7):500-11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00403. Epub 2012 Feb 27. Review. PMID: 22371850.; therefore, negative results do not exclude infection. As with any other test, the number of false-negative results increases with increasing disease prevalence in the community, while the negative predictive value decreases. Testing time varies among virologic testing methods: conventional cell culture takes between 3 and 10 days, rapid cell culture (eg, shell vials) from 1 to 3 days, immunofluorescence (DFA, IFA) from 1 to 4 hours, RT-PCR between 1 and 6 hours, and RIDT <30 minutes.

2. Serologic testing is of little practical importance.

1. Diagnosis of infection (laboratory-confirmed influenza). The diagnosis of influenza is based on positive results of virology tests.

2. Prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, in the influenza season, the diagnosis of influenza might have been considered in every patient with fever and respiratory signs and symptoms (sore throat, cough, or both). Although clinical presentation alone only allows for a diagnosis of ILI (infection with several microorganisms may produce similar signs and symptoms), during the peak influenza season ILI was predictive of influenza and therefore testing in healthy or nonseverely ill patients was not generally needed. With the ongoing circulation of SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory viruses, it is important to confirm the diagnosis with RT-PCR testing.

3. Classification of disease severity:

1) Severe or complicated influenza (warrants hospital admission) is associated with typical manifestations plus ≥1 of the following:

a) Clinical (tachypnea and other manifestations of dyspnea, hypoxia) and/or radiologic features (pneumonia) of lower respiratory tract infection, central nervous system (CNS) manifestations (seizures, encephalitis, encephalopathy), severe dehydration.

b) Secondary complications: Renal failure, multiple organ dysfunction, sepsis and septic shock, myocarditis, rhabdomyolysis.

c) Exacerbation of primary chronic diseases including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, chronic liver or kidney disease, diabetes.

d) Other serious conditions not listed above that require hospitalization.

e) Any signs and symptoms of disease progression (see below).

2) A progressive (worsening) course of the disease: Emerging signs and symptoms of severe or complicated influenza in patients who have been previously seen by a physician for uncomplicated influenza. The patient’s clinical status may deteriorate very rapidly (eg, within 24 h); signs and symptoms of progressive influenza warrant prompt reevaluation of the prior treatment and, in most cases, are an indication for hospital admission (below, items a-c). The signs and symptoms of progressive disease (alarming symptoms):

a) Signs and symptoms of lower respiratory tract involvement or heart failure: Dyspnea, cyanosis, hemoptysis, chest pain, hypotension, decreased hemoglobin oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry (SpO2).

b) Symptoms suggestive of CNS involvement: Altered mental status, loss of consciousness, somnolence, seizures, significantly decreased muscle strength, paralysis or paresis.

c) Features of severe dehydration: Dizziness and orthostatic hypotension, somnolence and altered mental status, low urine output.

d) Laboratory and/or clinical features of persistent viral infection or secondary invasive bacterial infection (eg, high-grade fever and other acute signs and severe symptoms persisting >3 days).

4. Risk factors for a severe course and complications of influenza (including hospitalization and death):

1) Age >65 years or <5 years (particularly <12 months).

2) Pregnancy (particularly the second and third trimesters).

3) Extreme obesity (body mass index ≥40 kg/m2).

4) Certain chronic conditions (irrespective of age): Respiratory (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma), cardiovascular (eg, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure), renal, liver, metabolic (including diabetes), hematologic (including hemoglobinopathies), immunodeficiency (primary, HIV infection, immunosuppressive therapy), other conditions affecting respiratory function or the ability to clear respiratory secretions (eg, cognitive impairment, spinal injury, seizures, and neuromuscular disorders).

Common cold and other viral respiratory tract infections (including COVID-19), bacterial respiratory tract infections. Less likely pharyngitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation, mononucleosis, acute HIV infection, malaria.

TREATMENTTop

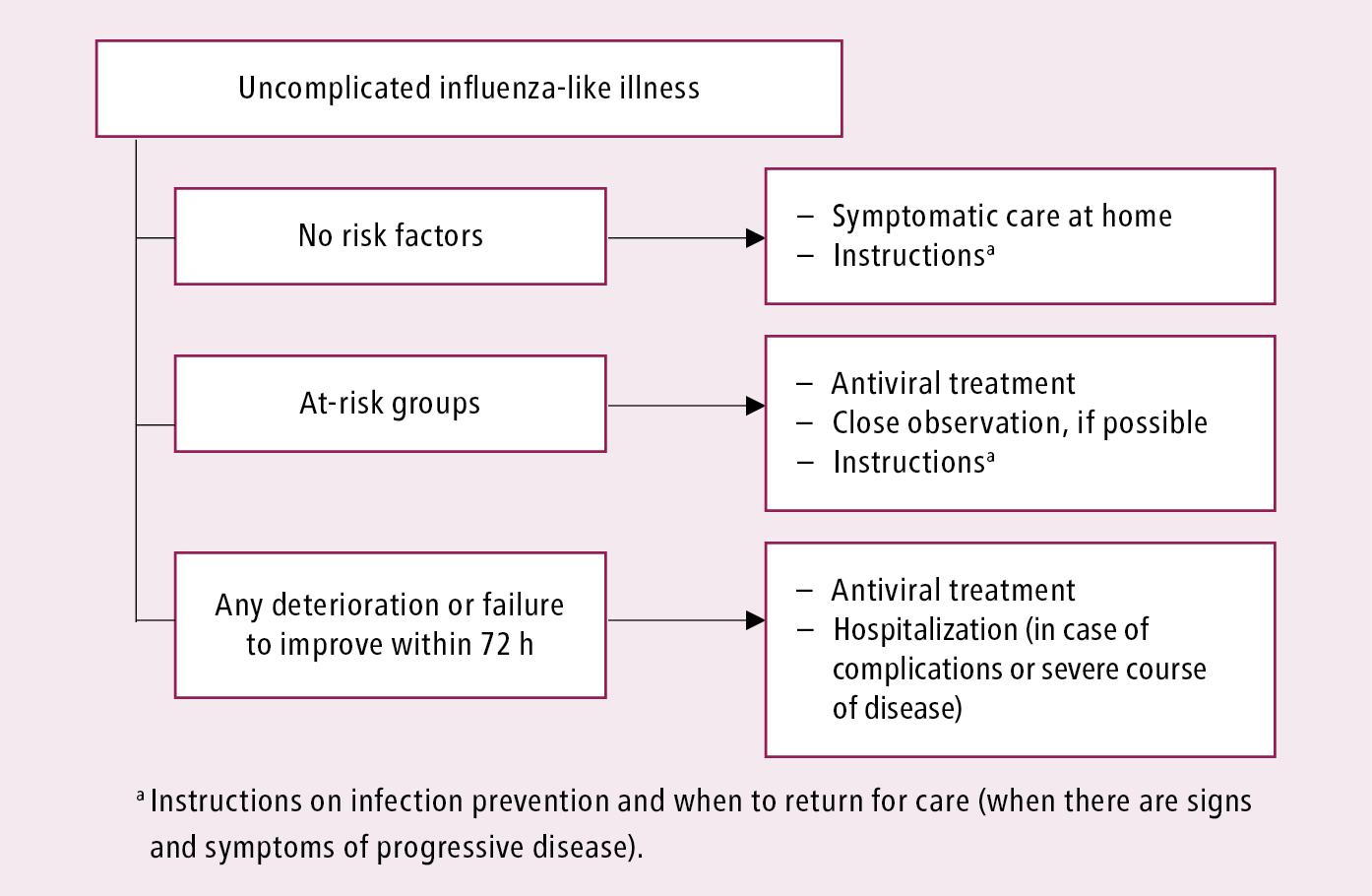

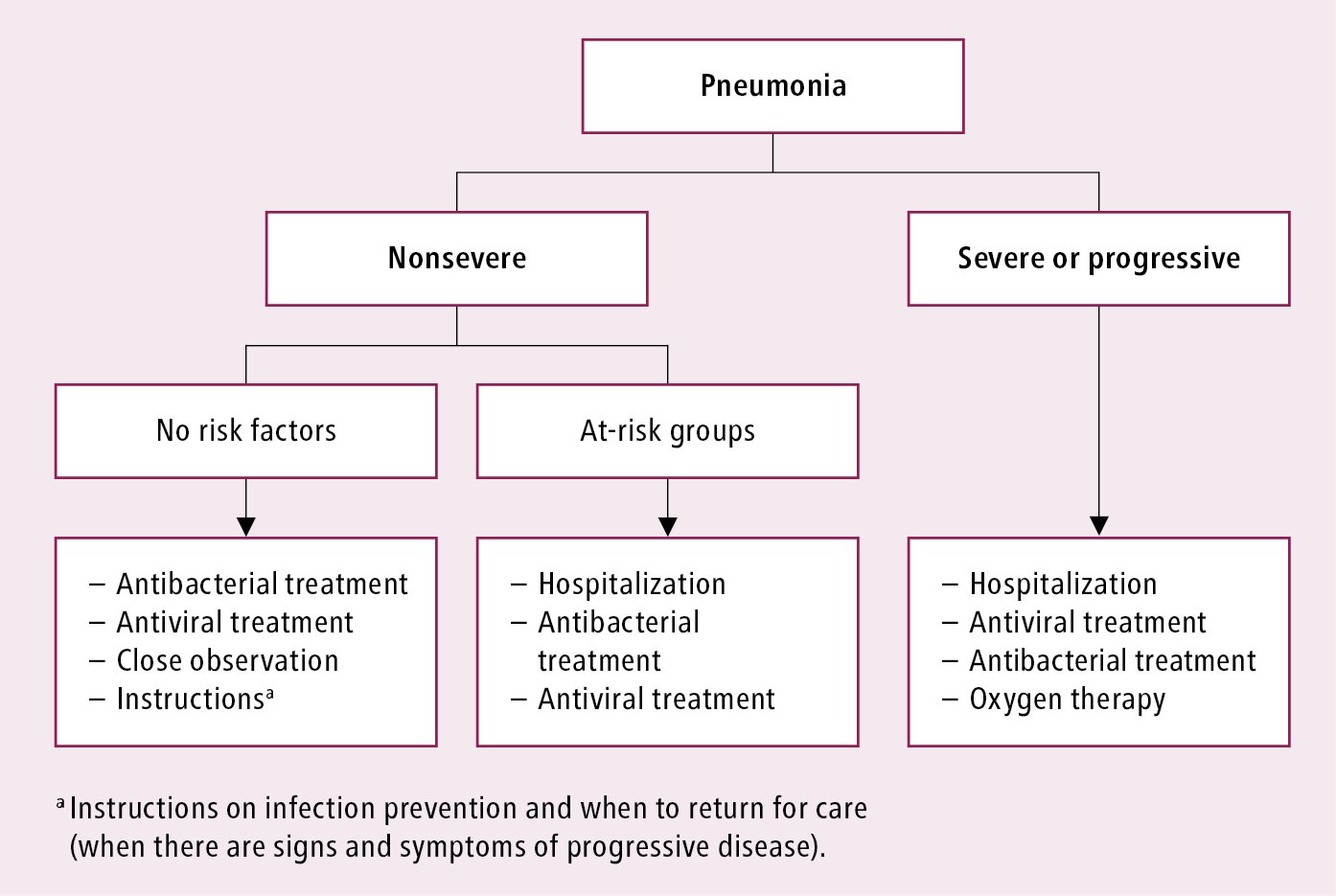

Management algorithms: Figure 10.11-1 and Figure 10.11-2.

1. Bed rest as required, adequate hydration, patient isolation (particularly to prevent contact with individuals at high risk for complications of influenza).

2. Antipyretics and analgesics: Acetaminophen (INN paracetamol), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (eg, ibuprofen); do not use acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) in children and adolescents <18 years of age due to the risk of Reye syndrome.

3. Cough suppressants, nasal decongestants, and isotonic or hypertonic saline nasal spray solution may be used as required.

4. Popular over-the-counter medications, such as vitamin C and rutoside, are not effective. There is no firm evidence of the beneficial effects of homeopathic remedies.

With different options available and lack of direct comparisons, our default choice is oseltamivir (longer period of availability and most data).

1. Antiviral agents for the treatment of influenza:

1) Neuraminidase inhibitors (active against influenza A and B viruses): Oseltamivir (oral), zanamivir (dry powder inhaler), peramivir (IV).

2) M2 inhibitors (only active against influenza A viruses): Amantadine and rimantadine.

3) Endonuclease inhibitor: Baloxavir.

Because the spectrum of resistance to antiviral agents changes every year, recommendations for empiric treatment are updated prior to each influenza season (or during the season, when necessary). The currently circulating influenza A (H3N2) and H1N1 2009 viruses are resistant to M2 inhibitors; therefore, these medications are not recommended for use against influenza A virus infections. However, almost all current influenza A and B virus strains are, with rare exceptions, susceptible to the neuraminidase inhibitors. Sporadic oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 2009 virus infections have been identified, but the public health impact has been limited to date. Oseltamivir and peramivir should not be used if an oseltamivir-resistant influenza strain is suspected. All oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 2009 strains are susceptible to zanamivir. Early initiation of antiviral treatment (optimally within 48-72 h of onset) in uncomplicated cases can reduce the symptom duration of influenza by <24 hours. However, data for the reduction of complications of influenza are quite limited, with more evidence derived from observational studies than from randomized trials.

Adverse events:

1) Oseltamivir: Nausea and vomiting (might be less severe if oseltamivir is taken with food), transient neuropsychiatric events (self-injury or delirium; the majority of reports were among Japanese adolescents and adults). It may impair the immune response to influenza vaccines.

2) Zanamivir: Bronchospasm (zanamivir is licensed only for use in persons without an underlying respiratory or cardiac disease). It does not impair the immune response to inactivated influenza vaccines.

3) Peramivir: Diarrhea. Serious skin reactions and transient neuropsychiatric events have been reported.

4) Baloxavir: The most common adverse event is diarrhea, but no adverse event was more common in baloxavir compared with placebo or oseltamivir in a phase 3 clinical trial.

2. Indications for treatment with neuraminidase inhibitors or an endonuclease inhibitor:

1) In patients with suspected or confirmed influenza of a severe or progressive course, or complications of influenza (see Diagnostic Criteria, above), we recommend starting oseltamivir as soon as possible (this includes also pregnant women).Evidence 2Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). For the effect on symptoms in previously healthy participants, Quality of Evidence is not downgraded. For the effect on reducing complications, Quality of Evidence downgraded to moderate because of imprecision, diagnostic uncertainty in measuring outcomes, indirectness to high risk individuals, and potential publication bias. The interpretation of existing evidence differs (see http://www.bmj.com/content/345/bmj.e7303). For the effect of neuraminidase inhibitors to reduce death in severely ill patients, Quality of Evidence is low on the basis of observational data. Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Spencer EA, Onakpoya I, Heneghan CJ. Oseltamivir for influenza in adults and children: systematic review of clinical study reports and summary of regulatory comments. BMJ. 2014 Apr 9;348:g2545. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2545. Review. PMID: 24811411; PMCID: PMC3981975. Kaiser L, Wat C, Mills T, Mahoney P, Ward P, Hayden F. Impact of oseltamivir treatment on influenza-related lower respiratory tract complications and hospitalizations. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Jul 28;163(14):1667-72. PMID: 12885681. Muthuri SG, Venkatesan S, Myles PR, et al; PRIDE Consortium Investigators, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in reducing mortality in patients admitted to hospital with influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus infection: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Respir Med. 2014 May;2(5):395-404. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70041-4. Epub 2014 Mar 19. Review. PMID: 24815805. If oseltamivir is not available or is contraindicated, or in the case of documented resistance of the isolated virus to oseltamivir, treat the patient with zanamivir.

2) In the case of a strong clinical suspicion of influenza or laboratory-confirmed influenza in a patient at high risk for a severe course or complications of influenza (see Diagnostic Criteria, above), we suggest starting oseltamivir as soon as possible after the onset of disease, regardless of the severity of clinical manifestations.Evidence 3Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). For the effect on symptoms in previously healthy participants, Quality of Evidence is not downgraded. For the effect on reducing complications, Quality of Evidence downgraded to moderate because of imprecision, diagnostic uncertainty in measuring outcomes, indirectness to high risk individuals, and potential publication bias. The interpretation of existing evidence differs (see http://www.bmj.com/content/345/bmj.e7303). For the effect of neuraminidase inhibitors to reduce death in severely ill patients, Quality of Evidence is low on the basis of observational data. Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Spencer EA, Onakpoya I, Heneghan CJ. Oseltamivir for influenza in adults and children: systematic review of clinical study reports and summary of regulatory comments. BMJ. 2014 Apr 9;348:g2545. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2545. Review. PMID: 24811411; PMCID: PMC3981975. Kaiser L, Wat C, Mills T, Mahoney P, Ward P, Hayden F. Impact of oseltamivir treatment on influenza-related lower respiratory tract complications and hospitalizations. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Jul 28;163(14):1667-72. PMID: 12885681. Muthuri SG, Venkatesan S, Myles PR, et al; PRIDE Consortium Investigators, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in reducing mortality in patients admitted to hospital with influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus infection: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Respir Med. 2014 May;2(5):395-404. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70041-4. Epub 2014 Mar 19. Review. PMID: 24815805.

In the majority of patients with mild to moderate influenza who are not at high risk for complications, as well as in patients who present in the convalescence phase, antiviral treatment is generally not necessary. For situations where it is important to reduce symptom duration (still within 24 h), we suggest oseltamivir.Evidence 4Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). For the effect on symptoms in previously healthy participants, Quality of Evidence is not downgraded. For the effect on reducing complications, Quality of Evidence downgraded to moderate because of imprecision, diagnostic uncertainty in measuring outcomes, indirectness to high risk individuals, and potential publication bias. The interpretation of existing evidence differs (see http://www.bmj.com/content/345/bmj.e7303). For the effect of neuraminidase inhibitors to reduce death in severely ill patients, Quality of Evidence is low on the basis of observational data. Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Spencer EA, Onakpoya I, Heneghan CJ. Oseltamivir for influenza in adults and children: systematic review of clinical study reports and summary of regulatory comments. BMJ. 2014 Apr 9;348:g2545. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2545. Review. PMID: 24811411; PMCID: PMC3981975. Kaiser L, Wat C, Mills T, Mahoney P, Ward P, Hayden F. Impact of oseltamivir treatment on influenza-related lower respiratory tract complications and hospitalizations. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Jul 28;163(14):1667-72. PMID: 12885681. Muthuri SG, Venkatesan S, Myles PR, et al; PRIDE Consortium Investigators, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in reducing mortality in patients admitted to hospital with influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus infection: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Respir Med. 2014 May;2(5):395-404. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70041-4. Epub 2014 Mar 19. Review. PMID: 24815805. Clinical judgment should be an important component of outpatient-treatment decisions. Long-term treatment with oseltamivir may lead to the development of drug resistance, particularly in immunocompromised patients. Influenza A H1N1 2009 virus is resistant to oseltamivir, yet susceptible to zanamivir.

3. Dosage and treatment regimens:

1) Oseltamivir (oral) in patients >40 kg or >12 years of age: 75 mg bid, usually for 5 days. If the treatment is not effective, continue oseltamivir for a longer time. There are probably no virologic or clinical advantages of a double dose of oseltamivir compared with a standard dose in patients with severe influenza admitted to hospital. In patients with creatinine clearance of 10 to 30 mL/min, a reduction of the treatment dose to 30 mg once daily and of the chemoprophylaxis dose to 75 mg every other day is recommended.

2) Zanamivir (dry powder inhaler): The recommended dosage is 2 inhalations (2 × 5 mg) bid for 5 days. Do not use zanamivir in nebulization because it contains lactose, which may affect the functioning of the nebulizer. No dose adjustment of inhaled zanamivir is recommended for a 5-day course of treatment in patients with either mild-to-moderate or severe impairment of renal function.

3) Peramivir: A single IV dose of 600 mg.

4) Baloxavir: A single dose: 40 mg for patients <80 kg, 80 mg for patients ≥80 kg.

Hospitalization is indicated in patients with severe or progressive influenza (see Diagnostic Criteria, above).

1. Initial patient assessment:

1) SpO2 should be monitored in every patient and maintained >90% in patients with pneumonia. In some patients (pregnant women, children), the recommended SpO2 is 92% to 95%.

2) In patients with dyspnea, perform chest radiography.

3) Perform (or repeat) RT-PCR assay for the influenza virus. A negative result in a patient with a strong clinical suspicion of influenza requires repeating the test every 48 to 72 hours.

4) Frequently reevaluate the patient, as the clinical deterioration may progress rapidly over hours.

2. Immediately after admission, start empiric treatment with oseltamivir (or an alternative first-line antiviral agent if seasonal recommendations have changed). In patients hospitalized because of complications of influenza, oseltamivir is usually continued for >5 days or ≥10 days (or until the resolution of signs and symptoms and/or virology test results confirm that the virus no longer replicates). If severe symptoms of influenza persist despite oseltamivir treatment in a patient with documented influenza, consider IV zanamivir or peramivir.

3. In patients with influenza-associated pneumonia (particularly if severe), combine oseltamivir with empiric antibiotic therapy according to the current recommendations for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Bacterial pneumonia in patients with influenza is most frequently caused by Staphylococcus aureus and pneumococci, but standard microbiologic diagnostics should be carried out in each patient. Prophylactic antibiotic use is not recommended. If clinical features do not suggest bacterial infection in a patient with laboratory-confirmed influenza, consider discontinuation of antibiotic treatment.

4. Mechanical ventilation is used when necessary (eg, in acute respiratory distress syndrome).

5. Glucocorticoids: High doses should be avoided in influenza pneumonia due to the risk of serious adverse effects, including opportunistic infections and prolonged viral replication. Administration of low-dose glucocorticoids may be considered in the case of septic shock requiring vasopressor therapy (see Sepsis and Septic Shock).

COMPLICATIONSTop

Complications of influenza:

1) Pneumonia:

a) Primary influenza-associated pneumonia: Persistent signs and symptoms of influenza. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, this was the most prevalent severe viral pneumonia during influenza seasons, which may progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome.

b) Secondary bacterial pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, or Haemophilus influenzae develops during recovery or convalescence (recurrence of fever, increasing dyspnea, cough, fatigue).

2) Streptococcal pharyngitis.

3) Exacerbation of concomitant chronic diseases.

4) Rare complications: Meningoencephalitis, encephalopathy, transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, myositis (in extreme cases with myoglobinuria and renal failure), myocarditis, pericarditis, sepsis, and multiple organ dysfunction.

5) An extremely rare complication (affecting mainly children): Reye syndrome, usually associated with the use of ASA.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONSTop

Pregnant women are at higher risk for complications from influenza, including an unfavorable pregnancy outcome (miscarriage, premature birth, and fetal distress). Carefully monitor pregnant women with suspected or confirmed influenza and consider antiviral treatment prior to obtaining virology results regardless of the intensity of symptoms. Administer acetaminophen (INN paracetamol) for pain and fever (ASA and NSAIDs are contraindicated in pregnancy). There are no adequate data on using doses of oseltamivir >75 mg every 12 hours. Oseltamivir and zanamivir are safe during breastfeeding (the principles of infection control have to be followed including wearing a face mask and frequent hand washing).

PREVENTIONTop

1. Vaccination (see Vaccines: Seasonal Influenza) is the basis of influenza prevention (there is no high quality evidence on its effects on patient-important outcomes, especially in high-risk groups).Evidence 5Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness of population and limitations of observational data. Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012 Jan;12(1):36-44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. Epub 2011 Oct 25. Review. Erratum in: Lancet Infect Dis. 2012 Sep;12(9):655. PMID: 22032844.

2. Hand hygiene: During the influenza season, hands should be washed frequently (10 times a day for 20 sec) with soap and water—or, preferably, an alcohol-based antiseptic—and dried with disposable paper towels, particularly in the case of close contact with sick individuals (eg, household, workplace, hospital, and outpatient contacts). Hand washing should be performed after every contact with a sick person, after using the toilet, before eating or touching the mouth or nose, upon returning home, after clearing the nose or covering the mouth while sneezing or coughing.

3. Wearing a protective face mask (eg, surgical, dental) when in close contact (within 1.5-2 m) with a sick person. The patient should also wear a face mask to minimize the risk of infecting others. Face masks should be discarded after each contact with a sick individual and replaced with new ones. Wearing prophylactic face masks by healthy persons when outdoors is not recommended. During medical procedures generating aerosols of respiratory secretions (eg, bronchoscopy, suctioning of respiratory secretions), face masks with an N95 respirator (or equivalent) as well as protective eyewear, gowns, and gloves should be used.

4. Other recommendations for hygiene during the influenza season include covering the mouth with a tissue while sneezing or coughing, disposing of the tissue in a waste basket, and washing hands thoroughly (if tissues are not available, it is recommended to sneeze or cough into an elbow or upper sleeve, not into the hands); avoiding face-to-face contact with other people; avoiding public gatherings; avoiding touching the mouth, nose, and eyes with unwashed hands; and frequent and thorough ventilation of rooms.

5. Patient isolation for 7 days from the onset of symptoms, and in the case of persistent symptoms, until 24 hours after the resolution of fever and acute respiratory symptoms. During this period patients with uncomplicated influenza should stay at home and limit their contacts with others to the necessary minimum. Longer isolation may be needed in immunocompromised patients.

6. Chemoprophylaxis (oral oseltamivir [75 mg once daily] or zanamivir [10 mg once daily] for a total of ≤10 days after the most recent known exposure) may be used in high-risk persons within 48 hours after a close contact (eg, within household) with a suspected or confirmed case, but it is not recommended as a routine procedure. Antiviral treatment of infected high-risk individuals is preferred (see Diagnostic Criteria, above), and this should be started as soon as possible after the onset of symptoms of influenza. Unvaccinated health care workers who sustain occupational exposures and were not using an adequate personal protective equipment at the time of exposure are also potential candidates for chemoprophylaxis. Clinical judgment is an important factor in making postexposure chemoprophylaxis decisions, which should take into account the exposed person’s risk for influenza complications (see Diagnostic Criteria), type and duration of contact (see Diagnostic Criteria), and recommendations from local or public health authorities. Chemoprophylaxis is not a substitute for influenza vaccination when influenza vaccine is available and not contraindicated.

FiguresTop

Figure 10.11-1. Initial clinical management of patients with uncomplicated influenza-like illness or influenza. See text for comments. Based on the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.

Figure 10.11-2. Initial clinical management of influenza-associated pneumonia. See text for comments. Based on the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.