Branda JA, Strle K, Nigrovic LE, et al. Evaluation of Modified 2-Tiered Serodiagnostic Testing Algorithms for Early Lyme Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Apr 15;64(8):1074-1080. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix043. PMID: 28329259; PMCID: PMC5399943.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme Disease. Updated August 26, 2024. Accessed October 16, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme

Lantos PM, Rumbaugh J, Bockenstedt LK, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Jan 23;72(1):e1-e48. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1215.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Lyme borreliosis is a bacterial inflammatory disease that may involve the skin, joints, nervous system, and heart.

1. Etiologic agent: Gram-negative spirochetes Borrelia spp transmitted by ticks. In Canada and the United States, the most common species is Borrelia burgdorferi; in Europe, it is most commonly Borrelia afzelii, Borrelia garinii, and rarely B burgdorferi. After being injected into the skin, the spirochetes migrate locally and form an early skin lesion (erythema migrans). Over the course of several days to weeks, the spirochetes may spread to several organs with blood or lymph.

2. Reservoir and transmission: Wild animals, especially rodents and white-tailed deer. Infection occurs through the bite of an infected Ixodes (hard, black legged) tick. The incidence of tick-borne diseases varies geographically and follows seasonable patterns that depend on the activity of ticks, which feed on human and animal blood and are active from spring until late fall. There have been no documented cases of human-to-human transmission.

3. Epidemiology: Epidemiology changes quickly as ticks migrate with the animal hosts. Readers are recommended to review their local epidemiology on a regular basis.

1) Canada: Southern British Columbia; Manitoba; Quebec; New Brunswick; southern, eastern, and northwestern Ontario; and part of Nova Scotia.

2) United States: Predominantly in the Northeast with smaller foci in the upper Midwest and Pacific Northwest.

3) Europe: Predominantly but not exclusively Central Europe, Scandinavia, and endemic regions in Russia.

4) South and Southeast Asia: Lyme borreliosis is rare in the region of South and Southeast Asia. However, in recent years sporadic cases have been reported in various countries of Asia including India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. The disease is likely present in Bangladesh as well, but there is still no available reported case.

4. Risk factors: Residence, tourism, or work in tick-infested endemic areas. Ticks must feed on the host for >24 hours in order to transmit Lyme disease. Stimulation of ticks attached to the skin (eg, by squeezing, applying gasoline or oil, burning) may increase transmission rate.

5. Incubation and contagious period: The incubation period refers to the early infection (stage 1; see below) and lasts from 3 to 30 days (in some cases up to 3 months) from the time of tick attachment. The patient is not infectious for contacts.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

Stages of the disease (these may overlap or occur simultaneously; usually not all signs and symptoms are present):

1. Early localized infection (stage 1):

1) Erythema migrans usually appears within ~7 (3-30) days after the tick bite. It is initially a red-colored spot or macula, which rapidly increases in diameter (>5 cm) and develops a bright-red outer border with partial central clearing (although it may be uniformly red) with clearly demarcated margins (Figure 10.3-1). The lesion is flat, painless, and does not cause itching. It rarely ulcerates. Multiple erythema migrans rashes are indicative of disseminated infection. Early infection may include flu-like symptoms.

2) Borrelial lymphocytoma is a rare manifestation of European Lyme borreliosis; it is a painless, bluish-red nodule, which most frequently develops on the pinna, nipple, or scrotum.

Erythema migrans and early systemic clinical features resolve spontaneously within 4 to 12 weeks regardless of antimicrobial treatment.

In some untreated patients relatively mild clinical symptoms persist for several years, while others develop signs and symptoms of late infection (these symptoms, such as arthritis, may be the first and only manifestation of the disease, even years after the tick bite).

2. Early disseminated infection (stage 2) may develop over several weeks to a few months after exposure:

1) Carditis (~5% of patients): Sudden-onset atrioventricular block or arrhythmia and other conduction disturbances. The block resolves with antibiotic treatment. Rarely Lyme disease may present as endocarditis or myocarditis.

2) Inflammatory neurologic involvement (neuroborreliosis): Simultaneous or gradual involvement of different levels of the central and peripheral nervous systems, which may manifest as lymphocytic meningitis (usually mild; headache may be the only manifestation) and cranial neuritis (paralysis or paresis; most commonly facial nerve palsy, which may be bilateral).

3. Late localized infection (stage 3) may develop weeks to months after exposure:

1) Arthritis: Most frequently involves one large joint (knee (90%), ankle, elbow), although sometimes several joints may be affected. Typically no severe systemic inflammatory reaction is present despite a major joint effusion. Recurrent flares lasting several days to weeks may occur; their frequency and severity diminish over time. Early flares may respond to a repeat course of antibiotics. Late flares may be antibiotic resistant (inflammatory rather than infectious) and may require anti-inflammatory therapy. Patients with HLA-DRB1 are more prone to develop a chronic inflammatory arthritis even after successful treatment for Lyme disease.

2) Chronic neuroborreliosis (very rare): Radiculitis and peripheral neuritis, peripheral polyneuropathy, chronic encephalomyelitis.

3) Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans: Reddish-violaceous skin lesions on distal limbs, usually asymmetric and appearing several years after the tick bite. Initially this manifests as inflammatory edema; later skin atrophy becomes the predominant sign (skin becomes thin, hairless, and has violaceous discoloration). The lesions are frequently accompanied by pain of adjacent joints and by paresthesias. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is more common in the case of infection with European Lyme strains than with B burgdorferi.

4. Coinfection: Ixodes ticks may also transmit Babesia microti, anaplasmosis, Borrelia miyamoto, and rarely the Powassan virus. In endemic regions up to 4% to 5% of patients who present with Lyme disease are coinfected with either babesiosis or anaplasmosis. Providers should have a high index of suspicion, especially for Babesia, in patients with severe presenting symptoms or persistent symptoms despite appropriate Lyme disease therapy.

5. Lyme disease in pregnancy: There are rare case reports of perinatal transmission of Lyme disease but no studies or expert consensus. Pregnant women diagnosed with Lyme disease should be treated appropriately for their stage at presentation. Tetracyclines should be avoided.

6. Concepts of chronic Lyme disease versus post-Lyme syndrome: The term chronic Lyme disease is sometimes used to describe nonspecific symptoms persisting for >3 months in a patient with negative Lyme antibodies. Current literature does not support active infection in the setting of a negative antibody results for patients with symptoms lasting >12 weeks and another etiology for their symptoms should be investigated. Post-Lyme syndrome refers to persistent symptoms lasting >6 to 12 months after appropriate antibiotic therapy in patients positive for Lyme antibody. Signs and symptoms of active inflammation should be excluded. Most patients do not require repeated or prolonged antibiotic therapy in the absence of documented inflammation, such as arthritis or uveitis.

DiagnosisTop

Erythema migrans rash with the appropriate epidemiologic risk factors is diagnostic of early (stage 1) Lyme disease. Patients with an erythema migrans rash in the right setting should be treated empirically, as antibodies are only positive 50% of the time.

A negative history of tick bite in a patient with erythema migrans does not preclude the diagnosis of Lyme disease. At most 80% of patients remember a prior tick bite.

Antibody testing for chronic symptoms in low-risk areas is not recommended due to the low positive predictive value.

Laboratory diagnosis is necessary to diagnose stage 2 or 3 Lyme disease.

Historically diagnosis has involved an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) confirmed with a Western blot, as discussed below. More recently the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Health Canada have approved a 2-tier testing approach using 2 ELISAs in a sequence. This modified 2-tier (MTT) testing has certain advantages, including up to 25% greater sensitivity for early disease, and is more easily automated. The MTT approach was found as sensitive as the traditional approach for stage 2 and 3 Lyme disease. This approach has not been validated in all regions and does not cross-react with different species of Borrelia, therefore a European Lyme disease antibody testing must be ordered separately if epidemiologic risk factors are present.

Historical diagnostic approach:

1) ELISA: Measurement of specific serum IgM levels. The ELISA is sensitive but not specific for Lyme disease. A negative ELISA result excludes Lyme disease unless the exposure was acute, for example, within the last 3 to 30 days. An inconclusive or positive ELISA must be confirmed with a Western blot.

2) Western blot: The Western blot confirms that a positive ELISA is actually due to Lyme disease. The Western blot measures both IgM and IgG:

a) IgM: Specific IgM antibodies are detectable in blood within 3 to 4 weeks from the moment of infection (they peak after 6-8 weeks) and gradually disappear over the next 4 to 6 months. Rarely, IgM may persist for years. A positive Western blot IgM result with a negative Western blot IgG result may represent early disease. An isolated positive IgM after >8 weeks of symptom onset is considered a false positive and other causes for the patient’s symptoms should be investigated; these patients do not require antibiotic therapy for Lyme disease.

b) IgG: Specific IgG antibody is detected within 6 to 8 weeks of the tick bite and remains positive for many years even in patients successfully treated with antibiotics. It should be interpreted within the context of clinical symptoms.

c) Central nervous system disease: In patients with neuroborreliosis, specific IgM or IgG are detected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Lymphocytic pleocytosis may be found both in early and late neuroborreliosis; however, in early cranial neuritis and late neuroborreliosis with peripheral nervous system involvement, CSF is usually normal.

The diagnosis of late Lyme borreliosis is made in patients who have a positive Lyme ELISA result with a confirmatory IgG Western blot and who have signs and symptoms of the disease persisting for ≥12 months.

TreatmentTop

1. Antibiotic treatment: The choice of the antibiotic and duration of treatment vary with disease manifestations (Table 10.3-1). Antibiotics are warranted for patients presenting with an erythema migrans rash and a risk of exposure to Lyme disease or those with a longer duration of symptoms who have a positive antibody for Lyme disease. No antibiotics are necessary for asymptomatic patients with an incidental positive IgG antibody. Antibiotic therapy used longer than indicated does not bring any medical benefits and does not improve patients’ quality of life.

2. Relapse versus reinfection versus persistent inflammation: Relapses are rare but may be more frequent in patients with arthritis who are HLA-B27–positive. Reinfection, which requires a new round of treatment, is possible and must be distinguished clinically from relapse, which requires extension of the recently completed treatment. Many patients can have persistent inflammatory symptoms in the absence of active infection and require only symptomatic support. Symptoms after appropriate treatment for the late stages of Lyme disease, particularly neuroborreliosis or arthritis, may persist for months to years.

Symptomatic treatment is used when necessary and may include, for instance, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and arthrocentesis with evacuation of joint effusion. Some patients with persistent postinfectious arthritis require disease-modifying agents.

PrognosisTop

Early appropriate antibiotic treatment is curative in >90% of patients. In the remaining group, late neurologic, articular, and cutaneous sequelae may develop.

PreventionTop

Nonspecific Protection Against Ticks (Mainstay of Prevention)

1. Covering the skin while hiking or working in meadows and forests, for instance, by wearing long-sleeved shirts, long pants tucked into socks, a baseball cap or a wide brim sun-hat, light-colored clothes (ticks are easier to spot), and high-top shoes.

2. Repellents: Tick repellents, preferably containing diethyltoluamide (DEET) (sprayed over clothes and exposed skin, except for the face) or permethrin (kills ticks on contact, should be sprayed onto clothes only).

3. Thorough full-body check upon each return from forests or meadows (particularly including inguinal and axillary areas, skin behind the ears, and skin folds). Ticks must be attached for ≥24 hours in order to transmit Lyme disease to humans. Prompt removal of ticks that have been feeding for <24 hours does not result in Lyme transmission.

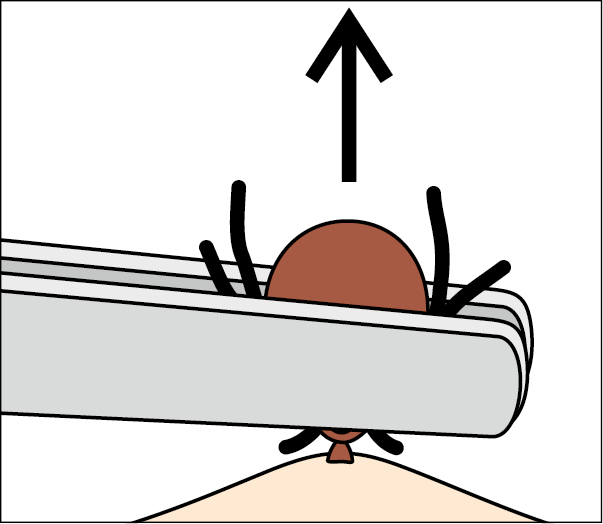

4. Prompt mechanical tick removal using a small hook, a lasso, or thin-tipped tweezers (Figure 10.3-2). If tick mouthparts remain in the skin (this does not increase the risk of infection), apply disinfectant to the affected area. Do not twist, scratch, squeeze, or burn the tick, and do not apply greasy liquids, alcohol, or gasoline, as this is actually associated with a higher risk of infection due to increasing the amount of tick’s vomit and saliva injected to the bloodstream. Disinfect the wound. After removing the tick, instruct the patient how to recognize the signs and symptoms of the disease, and advise to monitor the bite site for the next 30 days for signs of erythema migrans.

5. Protection of domestic animals (dogs, cats), which may bring ticks into the home: Tick repellents for animals, skin inspection, mechanical tick removal.

6. Postexposure prophylaxis: A single oral dose of 200 mg doxycycline is warranted only in the case of multiple tick bites in an adult who is not a permanent resident of an area endemic to Lyme borreliosis. To date, this approach has not been validated in children.

7. Vaccination: None available.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Clinical features |

Drug, route of administration (choose one) |

Dosage |

Treatment duration (days) |

|

Tick bite where rate of tick infections is <10% and/or tick was on for <24 h |

Monitoringb |

|

|

|

– Erythema migrans – Borrelial lymphocytoma – Cranial neuritisc (palsy) |

Doxycycline,b PO |

100 mg bid or 200 mg once daily |

14-21 |

|

Amoxicillin, PO |

500-1000 mg tid (children 50 mg/kg/d) |

14-21 | |

|

Cefuroxime axetil, PO |

500 mg bid (children 30 mg/kg/d) |

14-21 | |

|

Arthritis (first episode) |

Doxycycline, PO |

100 mg bid or 200 mg once daily |

14-28 |

|

Amoxicillin, PO |

500-1000 mg tid (children 50 mg/kg/d) |

14-28 | |

|

Cefuroxime axetil, PO |

500 mg bid (children 30 mg/kg/d) |

14-28 | |

|

– Neuroborreliosis – Arthritis (relapse) – Carditis |

Ceftriaxone, IV |

2000 mg once daily (children 50-75 mg/kg/d) |

14-28 |

|

Cefotaxime, IV |

2000 mg tid (children 150-200 mg/kg/d in 3-4 divided doses) |

14-28 | |

|

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans |

Doxycycline, PO |

100 mg bid or 200 mg once daily |

14-28 |

|

Amoxicillin, PO |

500-1000 mg tid |

14-28 | |

|

Ceftriaxone, IV |

2000 mg once daily |

14-28 | |

|

Cefotaxime, IV |

2000 mg tid |

14-28 | |

|

a Based on guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Polish Society of Epidemiology and Infectious Diseases (2020). b Tetracyclines are contraindicated in pregnancy and for children aged <8 years. Macrolides are considered third-line therapy and should be reserved for patients with contraindications to both beta-lactams and doxycycline. c Evaluate for signs and symptoms of meningitis. | |||

|

bid, 2 times a day; IV, intravenous; PO, oral; tid, 3 times a day. | |||

Figure 10.3-1. Typical features of erythema migrans, a sign of the early phase of Lyme borreliosis.

Figure 10.3-2. Tick removal using tweezers.