Baumgartner H, De Backer J, Babu-Narayan SV, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021 Feb 11;42(6):563-645. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa554. PMID: 32860028.

Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019 Apr 2;139(14):e637-e697. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000602. PMID: 30586768.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Coarctation of the aorta refers to a narrowing of the aorta, most frequently at the level of the aortic isthmus, that is, distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery, opposite to the ligamentum arteriosum. Usually collateral circulation develops via the internal thoracic arteries and intercostal arteries. The most common association is the presence of a bicuspid aortic valve (70%-75%). Intracranial aneurysms of the circle of Willis (the most common extracardiac anomaly) occur in up to 10% of patients. Turner syndrome is a commonly associated chromosomal abnormality.

Clinical FeaturesTop

1. Symptoms usually develop in the second or third decade of life and are associated with prestenotic hypertension in the aorta. However, there is an inverse relationship between the severity of stenosis and age at which symptoms develop. Other factors that determine severity and age at which symptoms occur are the presence and quality of collateral circulation and presence (or absence) of additional defects. Symptoms include headaches, epistaxis, and disturbances of vision. Natural history may include progressive left heart failure, premature coronary artery disease (CAD), intracranial hemorrhage, and aortic dissection/rupture.

2. Signs involve hypertension (blood pressures measured on the upper extremities are >10 mm Hg higher than those measured on the lower extremity artery; a difference ≥20 mm Hg indicates significant coarctation); different blood pressures on both brachial arteries in patients with stenosis including the origin of the left subclavian artery; weak or absent pulse on the femoral arteries; and rarely, intermittent claudication (usually collateral circulation is well developed). A continuous murmur caused by antegrade blood flow in the narrowed aorta is audible in the left interscapular area. Precordial murmurs caused by a coexisting aortic valve disease (a bicuspid aortic valve) may also be present. The presence of a systolic ejection click with or without a systolic murmur should make one suspect the presence of an associated bicuspid aortic valve. A sustained apical impulse and a fourth heart sound are found in many patients due to the underlying left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy.

3. Complications (may be fatal): Heart failure, aortic rupture or dissection, infection of the aortic wall, intracranial hemorrhage, and complications of rapidly developing CAD.

DiagnosisTop

Coarctation of the aorta is usually diagnosed in the course of workup of secondary hypertension or headache and is confirmed by imaging studies.

1. Electrocardiography (ECG): Features of LV hypertrophy. Atrial arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation can be seen.

2. Chest radiography (Figure 3.7-1): A characteristic indentation of the outline of the aorta (the so-called figure 3 configuration) and erosions (notching) of the lower edges of the ribs by well-developed collateral circulation, dilatation of the left subclavian artery and the ascending aorta.

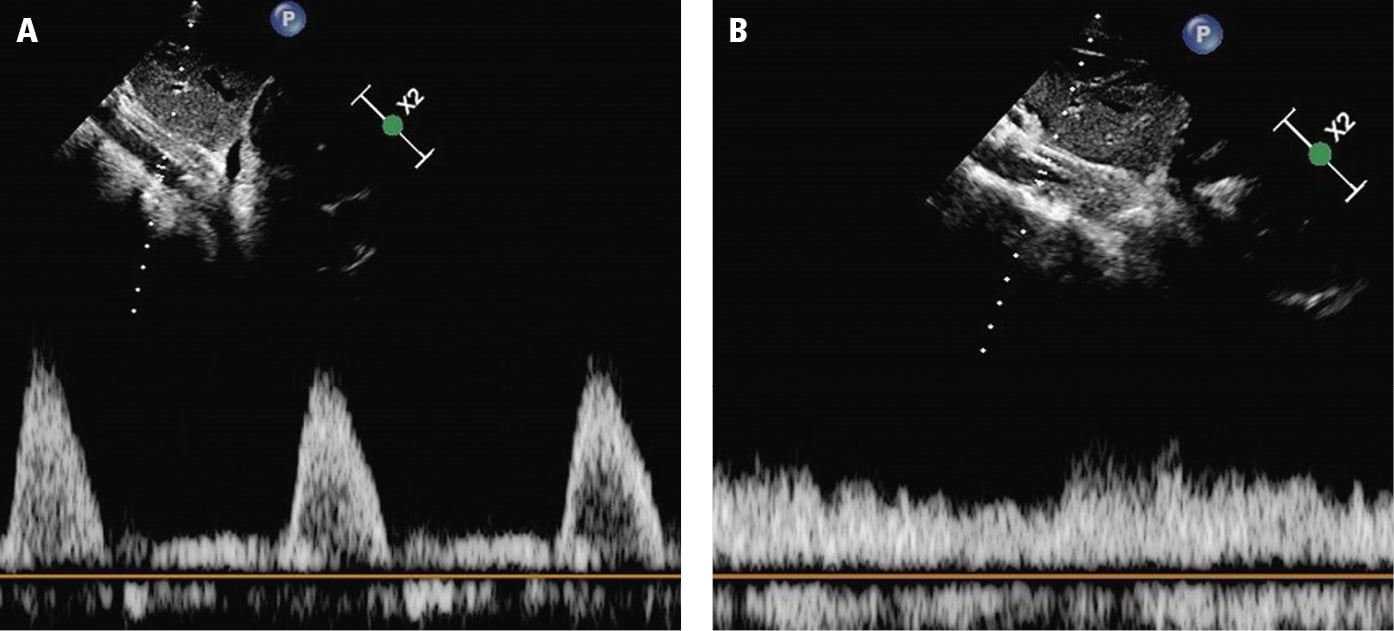

3. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is useful in assessing functional consequences, prestenotic and poststenotic pressure differences, and the nature of flow in the abdominal aorta. Frequently stenosis is not immediately apparent. In such cases assessment of the abdominal aorta by continuous wave Doppler echocardiography may show a coarctation of the aorta pattern (Figure 3.7-2) with low systolic velocities and diastolic runoff seen on pulsed wave Doppler evaluation of aortic flow. Assessment of the degree of LV hypertrophy as well as of the systolic and diastolic function are important components of the evaluation. The presence of a congenitally abnormal aortic valve and associated aortic dilatation are also assessed on echocardiography.

4. Traditional aortography, computed tomography angiography (CTA), or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA): Direct assessment of aortic stenosis, especially when qualifying the patient for surgery. MRA with hemodynamic assessment can be performed in many sites and has replaced conventional cardiac catheterization. CTA (including 3-dimensional reconstruction) can also provide anatomic evaluation of the presence and severity of coarctation. Catheterization is performed for evaluation of coronary arteries (preoperatively), in individuals with discrepant data from noninvasive assessment, as well as in those in whom percutaneous therapy is being considered. Imaging of intracerebral vessels is indicated in those with symptoms or clinical manifestations of an aneurysm.

TreatmentTop

Invasive treatment (surgical or percutaneous) in patients with a pressure gradient ≥20 mm Hg between the right upper extremity and the right lower extremity and blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg, significant LV hypertrophy, or a pathologic blood pressure response to exercise. Systemic hypertension frequently persists after surgery. Annual follow-up visits are recommended to detect possible restenosis as well as local site complications (such as pseudoaneurysms) and the development of premature CAD. In patients with an associated bicuspid aortic valve continued surveillance of the valve is recommended.

FIGURESTop

Figure 3.7-1. Chest radiography of a patient with coarctation of the aorta: the so-called figure 3 sign, dilatation of the ascending aorta, notching of the inferior border of the ribs.

Figure 3.7-2. Abdominal aortic pulsed wave Doppler patterns: A, normal pattern; B, abnormal pattern of coarctation of the aorta. Figure courtesy of Dr Manojkumar Rohit.