Kulikowski J, Parthasarathi U. Special Syndromes: Serotonin Syndrome, Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome, and Catatonia. In: Fenn HH, Hategan A, Bourgeois JA, eds. Inpatient Geriatric Psychiatry: Optimum Care, Emerging Limitations, and Realistic Goals. Springer; 2019:277-292.

Pelzer AC, van der Heijden FM, den Boer E. Systematic review of catatonia treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018 Jan 17;14:317-326. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S147897. PMID: 29398916; PMCID: PMC5775747.

Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s Concise Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry. 4th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Freudenreich O, Goff DC, Henderson DC. Antipsychotic Drugs. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2016: 475-488.e6.

Tse L, Barr AM, Scarapicchia V, Vila-Rodriguez F. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome: A Review from a Clinically Oriented Perspective. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(3):395-406. doi: 10.2174/1570159x13999150424113345. PMID: 26411967; PMCID: PMC4812801.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Gardner DM, Baldessarini RJ, Waraich P. Modern antipsychotic drugs: a critical overview. CMAJ. 2005 Jun 21;172(13):1703-11. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041064. PMID: 15967975; PMCID: PMC1150265.

IntroductionTop

Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPSs), catatonia, serotonin syndrome, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) can be seen in many medical environments, including acute and tertiary psychiatric settings, the emergency department, and other medical units. These conditions can be difficult to identify and distinguish and have potentially serious consequences if they are not recognized in a timely manner. They often occur as a result of medication initiation, titration, and discontinuation, and in some cases due to medical conditions (eg, neurologic and neurodegenerative diseases, bipolar and depressive disorders). Differential diagnosis is broad and physical examination is imperative for diagnosis and guiding treatment. This chapter will review these syndromes as adverse effects from psychotropic medications.

Common comparative features and management of NMS, serotonin syndrome, and catatonia: Table 16.2-1.

Extrapyramidal SymptomsTop

EPSs are defined as abnormal movements resulting from medication. EPSs are most often associated with first-generation antipsychotics and less commonly associated with second-generation antipsychotics. They comprise acute dystonia, drug-induced parkinsonism, akathisia, and tardive dyskinesia (Table 16.2-2). The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) refers to these conditions as “medication-induced movement disorders.”

1. Clinical features: Acute dystonia is characterized by abnormal and prolonged contraction of any muscle group. The muscles most commonly affected include the muscles of the eyes (causing oculogyric crisis), head, neck (causing torticollis or retrocollis), limbs, or trunk. The risk is elevated in males, individuals aged <30 years, and those treated with high doses of high-potency antipsychotics (eg, haloperidol). Onset is likely to occur early in treatment, although dystonia can occur at any time during the course of treatment, including dose increases.

2. Etiology: Incidence rates of dystonia decrease with age. With each year that a patient is treated with an antipsychotic, the risk is decreased by 4%. These movements are thought to occur as a result of dopamine hyperactivity in the basal ganglia as the levels of high-potency antipsychotics fall between treatments. The highest risk occurs with IM forms of antipsychotics, but oral antipsychotics can also cause this condition.

3. Treatment: The mainstay of treatment for acute dystonic symptoms is anticholinergic medication, such as benztropine or diphenhydramine.Evidence 1Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness (older studies) and imprecision. Stern TA, Anderson WH. Benztropine prophylaxis of dystonic reactions. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1979 Mar 28;61(3):261-2. doi: 10.1007/BF00432269. PMID: 36644. The risks and benefits of using these agents must be assessed, as the category of anticholinergic medications comes with adverse effects particularly profound in the older adult population. Benztropine and diphenhydramine can be used orally or IM to treat acute reactions. Other options include reducing the dose of the antipsychotic agent (if feasible) or switching from a first-generation to a second-generation antipsychotic or a lower-potency antipsychotic.

1. Clinical features: Signs of medication-induced parkinsonism parallel symptoms of Parkinson disease, which include tremor, muscular rigidity, flattened affect, akinesia (loss of movement or difficulty initiating movement), or bradykinesia (slow movements). These features can be confused with depression or negative symptoms of schizophrenia and warrant identification. The risk has a bimodal age distribution and is increased in the young and older adult population. Features often occur within the first 5 to 90 days of treatment initiation, upon increasing the dose of an antipsychotic, or following dose reduction of a medication used to treat parkinsonism.

2. Etiology: Parkinsonism occurs as a result of blockade of the dopamine D2 receptors in the caudate within the nigrostriatal pathway, where dopaminergic neurons terminate. High-potency antipsychotics carry the highest risk, including other antipsychotics that have little anticholinergic activity. Common examples of high- versus low-potency first-generation antipsychotics: Table 16.2-3; keep in mind that potency is a reflection of the therapeutic dose in mg (a high dose of a low-potency drug may have more effects than a low-dose of a high-potency drug).

3. Treatment: Treatment of medication-induced parkinsonism includes the use of anticholinergic agents like benztropine and diphenhydramine.Evidence 2Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias (evidence limited to clinician experience) and imprecision (small studies). Dayalu P, Chou KL. Antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal symptoms and their management. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008 Jun;9(9):1451-62. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.9.1451. PMID: 18518777. Mamo DC, Sweet RA, Keshavan MS. Managing antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism. Drug Saf. 1999 Mar;20(3):269-75. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199920030-00006. PMID: 10221855. These medications should be withdrawn after 4 to 6 weeks to determine if tolerance for parkinsonian effects has developed. Approximately half of patients treated with antipsychotics that experience parkinsonian symptoms will require ongoing anticholinergic treatment. Importantly, these symptoms can persist after the agent responsible for parkinsonian symptoms has been withdrawn. This phenomenon can be seen for up to 3 months in the older adults and ~2 weeks in the general population. Clinicians may continue anticholinergic medications if these symptoms persist following discontinuation of high-potency antipsychotics.

1. Clinical features: Akathisia is characterized by a subjective experience of restlessness that is often accompanied by observed fidgety movements of the legs, rocking from foot to foot, pacing, or inability to sit or stand still in those treated with antipsychotic medication. It is an uncomfortable sensation that can occur after the first dose of the medication and typically within weeks of initiation or dose increase. Akathisia may also arise after a medication used to treat akathisia is discontinued or decreased. The condition has been associated with increased self-harm and poor outcomes; thus, identification is important.

2. Etiology: Pathophysiology is not well understood. The condition has been associated with many psychotropics, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, and sympathomimetics. Middle-aged women appear to have the highest rates of this adverse effect. Aripiprazole, a second-generation antipsychotic, carries a high risk of akathisia.

3. Treatment: The Barnes Akathisia Scale (simpleandpractical.com) can be used to help identify and monitor for akathisia. Once akathisia is identified, the responsible agent should be decreased. If this is not feasible, medications to treat for akathisia include beta-adrenergic receptor antagonists (eg, propranolol). Benzodiazepines can be used, although risks and benefits should be assessed, including consideration to switch the medication responsible for akathisia.Evidence 3Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias (evidence limited to clinician experience) and imprecision (small studies). Lohr JB, Eidt CA, Abdulrazzaq Alfaraj A, Soliman MA. The clinical challenges of akathisia. CNS Spectr. 2015 Dec;20 Suppl 1:1-14; quiz 15-6. doi: 10.1017/S1092852915000838. PMID: 26683525. Pringsheim T, Gardner D, Addington D, et al. The Assessment and Treatment of Antipsychotic-Induced Akathisia. Can J Psychiatry. 2018 Nov;63(11):719-729. doi: 10.1177/0706743718760288. Epub 2018 Apr 23. PMID: 29685069; PMCID: PMC6299189.

1. Clinical features: Tardive dyskinesia is defined as involuntary athetoid or choreiform movements often involving the tongue, lower face, jaw, and extremities. This can also involve the muscles of the pharynx, diaphragm, and trunk muscles. Movements typically occur after several months of treatment with an antipsychotic agent. The risk is ~5% per year and increases with each year of treatment, equating to a lifetime risk of up to 50%. These movements may occur after a shorter duration of treatment in older adults. Tardive dyskinesia can also arise after the responsible agent has been decreased or discontinued and is referred to as “withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia.” This is typically time-limited to ~4 to 8 weeks.

2. Etiology: Pathophysiology is not well understood; however, first-generation antipsychotics tend to have a higher risk profile. Patients who are admitted to the hospital for long periods are 20% to 40% more likely to experience symptoms of tardive dyskinesia. It appears to be exacerbated by stress and remits with sleep. Women are typically more often affected than men. Children, individuals aged >50 years, and those with a history of brain damage and mood disorders appear to be at higher risk. Tardive dyskinesia in older adults is less likely to resolve, although between 5% and 40% of all cases remit.

3. Treatment: Preventative measures should be the first line of treatment, limiting the use of antipsychotics to only where indicated and at the lowest possible dose. Consider the adverse-effect profiles of first- and second-generation antipsychotics, as older (first-generation) antipsychotics have an elevated risk. Clozapine has a low risk for tardive dyskinesia and switching to this agent can lead to a reduction of movements, given the drug’s low affinity for D2 receptors and higher affinity for antagonism of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptors.Evidence 4Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to potential bias and imprecision (small studies). Pardis P, Remington G, Panda R, Lemez M, Agid O. Clozapine and tardive dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2019 Oct;33(10):1187-1198. doi: 10.1177/0269881119862535. Epub 2019 Jul 26. PMID: 31347436.

Symptoms of tardive dyskinesia may persist in some cases, and thus patients should be monitored closely for abnormal movements using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (www.aacap.org). Once abnormal movements have been identified, the clinician should consider decreasing, stopping, or switching the medication to clozapine or another second-generation antipsychotic. Although not yet available in Canada, there are 2 medications recently approved by the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) to treat tardive dyskinesia: valbenazine and deutetrabenazine. Both are used in specialized settings with experience in treating this condition.

CatatoniaTop

Catatonia is a multifactorial disorder that can result in the context of psychotic, bipolar, and major depressive disorders and other medical conditions. The DSM-5 has separated catatonia into 2 entities to identify the cause related to a psychiatric disorder or a physical illness. Catatonia is often underrecognized by physicians on inpatient units.

1. Etiology: Catatonia is commonly associated with primary psychiatric (eg, bipolar, major depressive, psychotic) disorders. The condition can also arise secondary to systemic medical and neurologic disorders, drug intoxication, or drug withdrawal. Abrupt discontinuation of long-term benzodiazepines may also precipitate catatonia. Catatonia in the older adult population is often associated with a systemic medical condition versus a primary psychiatric presentation and may co-occur with delirium, making diagnosis difficult to recognize. The mechanism underlying catatonia remains unclear, but it may include dysfunction of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor. It has also been hypothesized as a movement disorder. Differential diagnosis includes selective mutism, metabolic-induced stupor, Parkinson disease, malignant hyperthermia, and locked-in syndrome (ie, a condition that causes paralysis of nearly all voluntary muscles, except for vertical eye movements and blinking).

2. Clinical features: Catatonia can occur in 3 forms: retarded, excited, or mixed. The most commonly identified signs of catatonia include the retarded form, with mutism and stupor. Symptoms may fluctuate during presentation from stupor and mutism to agitation and odd posturing. Patients may present with hyperthermia, which requires acute intervention. According to the DSM-5, criteria for catatonia include ≥3 out of 12 features: stupor, cataplexy, waxy flexibility, mutism, negativism, posturing, mannerisms, stereotypy, agitation, grimacing, echolalia, echopraxia. If catatonia is associated with a systemic medical or neurologic condition, there must be evidence to support this from the medical history or examination.

3. Management: For catatonia secondary to a psychiatric disorder or systemic medical condition, it is imperative that the underlying condition be treated. Benzodiazepines are the mainstay of treatment.Evidence 5Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to insufficient high-quality evidence studies, imprecision, and potential bias (no data were available for benzodiazepines compared with placebo or standard care). Pelzer AC, van der Heijden FM, den Boer E. Systematic review of catatonia treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018 Jan 17;14:317-326. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S147897. PMID: 29398916; PMCID: PMC5775747. Huang YC, Lin CC, Hung YY, Huang TL. Rapid relief of catatonia in mood disorder by lorazepam and diazepam. Biomed J. 2013 Jan-Feb;36(1):35-9. doi: 10.4103/2319-4170.107162. PMID: 23515153. Zaman H, Gibson RC, Walcott G. Benzodiazepines for catatonia in people with schizophrenia or other serious mental illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Aug 5;8(8):CD006570. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006570.pub3. PMID: 31425609; PMCID: PMC6699646. The initial dose is lorazepam 1 mg IV every 6 hours. IV route provides a rapid onset of action; however, IM and oral administration are adequate for treatment. Lorazepam can be increased to 2 mg every 6 hours should no improvement occur with the 1-mg dosing. Lorazepam should be tapered slowly, as abrupt discontinuation could result in a reemergence of a catatonic state. If there is no response with lorazepam within 48 to 72 hours, electroconvulsive therapy should be strongly considered.

Serotonin SyndromeTop

Serotonin syndrome is an adverse effect of serotonergic agonism (potentiation of action) in the central and peripheral nervous system as a result of therapeutic treatment, overdose, or drug interactions. The early stages of the syndrome can be difficult to identify and are often missed or misidentified. Symptoms can be mild and resolve on their own; however, severe cases can lead to medical sequelae causing organ failure and death. Serotonin syndrome can occur in all ages, although older individuals are at higher risk due to changes that occur in drug metabolism with age.

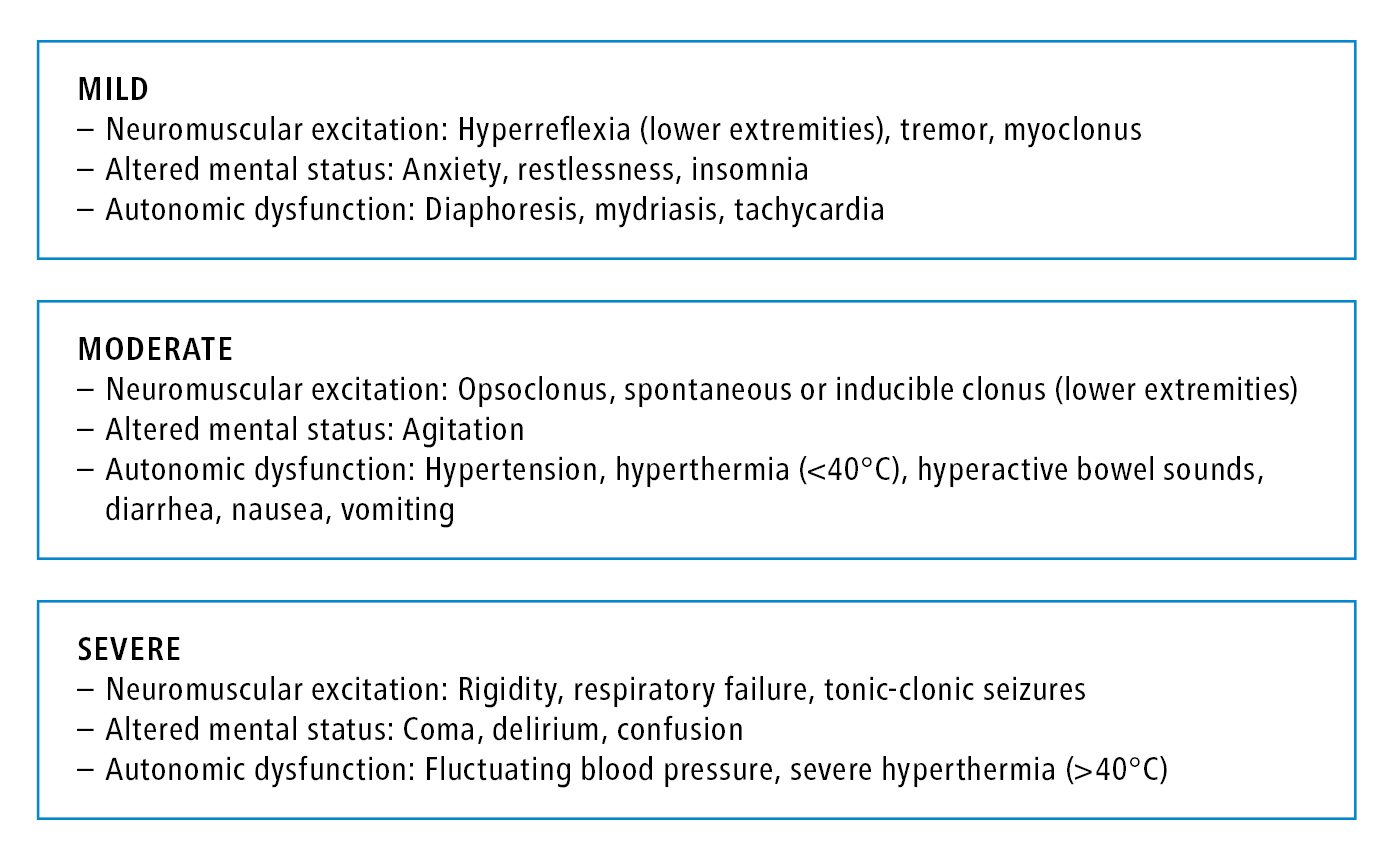

1. Etiology: Pharmacologic mechanisms that lead to serotonin syndrome include decreased serotonin breakdown, decreased serotonin reuptake, increased serotonin precursors or agonists, increased serotonin release, and drug-drug interactions. The condition can result secondary to a number of serotonergic agents (Table 16.2-4) with a classic triad of autonomic instability (from diaphoresis and tachycardia to hyperthermia), neuromuscular hyperactivity (tremor to rigidity), and altered mental status (from mild agitation to coma). Those occur to a varying degree in mild, moderate, and severe forms (Figure 16.2-1).

Neurologic findings specific to serotonin syndrome include clonus and hyperreflexia that are more pronounced in the lower extremities. In severe cases the resulting hyperthermia from muscle rigidity can lead to rhabdomyolysis, myoglobinuria, renal failure, metabolic acidosis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and death.

2. Management: Discontinuation of the serotonergic agents should be the first step in management. Treatment should then follow with supportive measures. Mild cases can resolve within 24 hours, although vital signs and the airway should be closely monitored to dictate next steps of treatment. Antipyretics should be avoided, as hyperthermia in serotonin syndrome is peripherally mediated due to increased muscle tone, which can be managed with benzodiazepines to prevent seizures and hypertonia. The antihistamine cyproheptadine can be effective in severe cases from case reports, although administration is limited to oral formulation or by a nasogastric tube. The initial dose of cyproheptadine is 4 to 8 mg, up to a maximum of 20 mg daily based on clinical improvement.Evidence 6Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, small sample size, and potential bias. Frank C. Recognition and treatment of serotonin syndrome. Can Fam Physician. 2008 Jul;54(7):988-92. PMID: 18625822; PMCID: PMC2464814. Graudins A, Stearman A, Chan B. Treatment of the serotonin syndrome with cyproheptadine. J Emerg Med. 1998 Jul-Aug;16(4):615-9. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(98)00057-2. PMID: 9696181. McDaniel WW. Serotonin syndrome: early management with cyproheptadine. Ann Pharmacother. 2001 Jul-Aug;35(7-8):870-3. doi: 10.1345/aph.10203. PMID: 11485136.

Neuroleptic Malignant SyndromeTop

The DSM-5 classifies NMS under “medication-induced movement disorders and other adverse effects of medication.” The presentation of NMS can have features similar to serotonin syndrome and thus can be misdiagnosed. The condition can be life-threatening, with fatality rates between 10% and 20%, which is why early identification is necessary for treatment purposes.

1. Etiology: The pathophysiology of NMS is not well understood. However, it is thought to be due to dopamine blockade causing hypothalamic dysfunction, with the blockade leading to muscle contraction and temperature dysregulation. Both first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics carry a risk of NMS with an incidence rate of 0.01% to 0.02% among those treated with antipsychotic medication. The risk is highest within the first 2 weeks of treatment during titration to therapeutic doses and is seen most often in young males. NMS can be precipitated by the concurrent use of ≥1 antipsychotic, abrupt cessation of dopaminergic medications (eg, levodopa), and with use of parenterally administered antipsychotics. Other risk factors include dementia (major neurocognitive disorders), dehydration, and malnutrition, particularly iron deficiency. Mood stabilizers including carbamazepine and valproic acid have also been identified to cause NMS-like symptomatology.

From the time of drug initiation, NMS can be seen within 24 hours to up to 30 days. Once the offending agent has been discontinued, the syndrome is often self-limited, although it may be prolonged if the antipsychotic is in a long-acting injectable form. The risk of recurrence appears to have a temporal agreement with reinitiation of the antipsychotic; however, quantified risk has not been established. There are no laboratory tests specific to NMS, although differential diagnosis should remain broad and physical examination should be completed. Differential diagnosis includes substance intoxication and withdrawal, serotonin syndrome, malignant hyperthermia, central nervous system infections, inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, status epilepticus, and subcortical lesions, as well as adrenal and thyroid dysfunction.

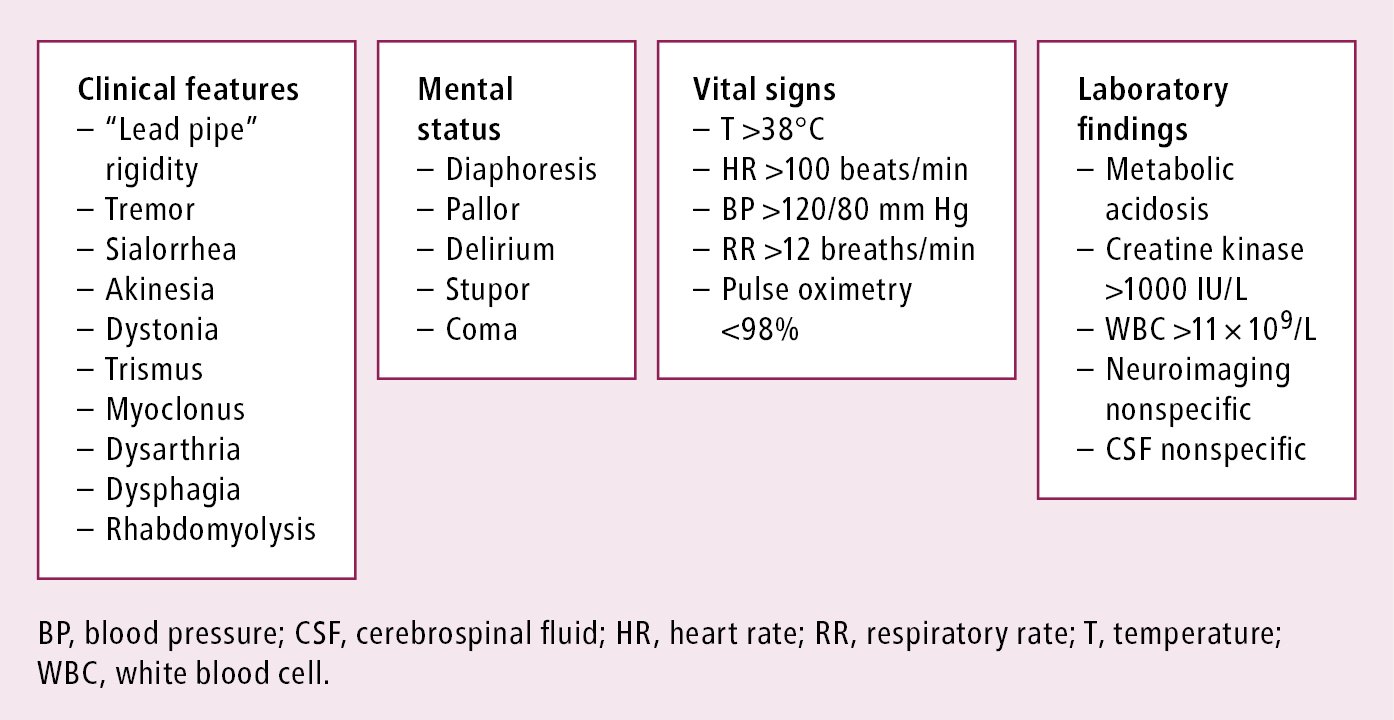

2. Clinical features: Presenting features of NMS include hyperthermia (>38 degrees Celsius), autonomic instability, rigidity, fluctuations in mood, and altered mental status. Rigidity is characterized as “lead pipe” and is resistant to anticholinergic treatment (Figure 16.2-2). Laboratory tests may demonstrate leukocytosis, metabolic acidosis, hypoxia, and elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels. Neuroimaging studies and cerebrospinal fluid analysis are nonspecific and generally normal.

3. Management: For mild cases, supportive treatment is recommended with fluid and electrolyte replacement as needed. Vital signs including temperature should be monitored, with cooling measures introduced as necessary. Physical examination should monitor cardiac, respiratory, and volume status. The risk of rhabdomyolysis is elevated and thus kidney function and CK should be monitored with laboratory tests. To decrease muscle rigidity and agitation, lorazepam can be beneficial in mild cases. The use of dopamine agonists in severe cases may shorten courses of NMS.Evidence 7Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to evidence limited to expert clinician opinion, imprecision, and small studies. Rosenberg MR, Green M. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Review of response to therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1989 Sep;149(9):1927-31. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.9.1927. PMID: 2673115. Trollor JN, Sachdev PS. Electroconvulsive treatment of neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a review and report of cases. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999 Oct;33(5):650-9. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.00630.x. PMID: 10544988. Tse L, Barr AM, Scarapicchia V, Vila-Rodriguez F. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome: A Review from a Clinically Oriented Perspective. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(3):395-406. doi: 10.2174/1570159x13999150424113345. PMID: 26411967; PMCID: PMC4812801. Oral agents include bromocriptine 2.5 mg bid or tid or amantadine 200 to 400 mg daily in divided doses. IV dantrolene has also demonstrated efficacy and should be used in doses of 1 to 10 mg/kg for daily IV administration and 50 to 600 mg daily for oral treatment. If pharmacotherapy is ineffective, electroconvulsive therapy may be warranted.Evidence 8Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to evidence limited to expert clinician opinion, imprecision, and small studies. Rosenberg MR, Green M. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Review of response to therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1989 Sep;149(9):1927-31. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.9.1927. PMID: 2673115. Trollor JN, Sachdev PS. Electroconvulsive treatment of neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a review and report of cases. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999 Oct;33(5):650-9. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.00630.x. PMID: 10544988. Tse L, Barr AM, Scarapicchia V, Vila-Rodriguez F. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome: A Review from a Clinically Oriented Perspective. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(3):395-406. doi: 10.2174/1570159x13999150424113345. PMID: 26411967; PMCID: PMC4812801.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

NMS |

Serotonin syndrome |

Catatonia |

|

Etiology |

||

|

Dopamine blockade causing hypothalamic dysfunction |

Serotonergic agonism in central and peripheral nervous system secondary to: – Decreased serotonin breakdown – Decreased serotonin reuptake – Increased serotonin precursors or agonists – Increased serotonin release – Drug-drug interactions |

GABA receptor dysfunction vs movement disorder |

|

Risk factors |

||

|

– ≥1 antipsychotic use – Parenteral antipsychotics – Titration of antipsychotics – Cessation of dopaminergic agents – Young age – Dehydration – Malnutrition – Dementia |

– >1 serotonergic agent (table 16.2-4) – Older age (drug metabolism) |

– Bipolar and major depressive disorders – Psychotic disorders – Systemic medical disorders – Abrupt discontinuation of benzodiazepines |

|

Clinical features |

||

|

– Hyperthermia (≥38 degrees Celsius) – Autonomic instability (hypertension, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypoxia) – Altered mental status (delirium, stupor, coma) – Muscular rigidity (“lead pipe,” resistant to anticholinergic treatment) – Tremor – Sialorrhea – Akinesia – Dystonia – Trismus – Myoclonus – Dysarthria – Dysphagia – Pallor – Rhabdomyolysis |

– Hyperthermia (moderate <40 degrees Celsius; severe >40 degrees Celsius) –Altered mental status (agitation, restlessness, anxiety, delirium, confusion, coma) – Autonomic instability (hypertension, tachycardia, diaphoresis, mydriasis, hyperactive bowel sounds, GI upset [nausea, vomiting, diarrhea]) – Neuromuscular hyperactivity (hyperreflexia [lower extremities], myoclonus, tremor, opsoclonus, spontaneous or inducible clonus [lower extremities], respiratory failure, tonic-clonic seizures) |

≥3 symptoms of: – Stupor – Cataplexy – Waxy flexibility – Mutism – Negativism – Posturing – Mannerisms – Stereotypy – Agitation – Grimacing – Echolalia – Echopraxia |

|

Treatment |

||

|

– Discontinue antipsychotic – Supportive treatment – Dopamine agonist: bromocriptine, amantadine – Muscle relaxant: dantrolene – Electroconvulsive therapy |

– Discontinue serotonergic agent – Supportive treatment – Benzodiazepine: lorazepam – Antihistamine: cyproheptadine |

– Benzodiazepine: lorazepam – Electroconvulsive therapy |

|

Differentiating features of NMS and serotonin syndrome: 1) Bowel sounds: Normal or decreased (NMS) vs hyperactive (serotonin syndrome). 2) Reflexes: Slow, depressed (NMS) vs hyperreflexia, clonus (serotonin syndrome). 3) Muscle rigidity: Increased rigidity in all muscle groups (NMS) vs increased rigidity primarily in lower extremities (serotonin syndrome). |

||

|

GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; GI, gastrointestinal. |

||

|

Type of EPS |

Clinical features |

Treatment |

|

Acute dystonia |

Acute muscle spasms: – Eyes – Head – Neck – Limbs – Trunk |

– Benztropine 2 mg IM and continue 1-2 mg PO bid for 2-3 days; or – Diphenhydramine 25-50 mg IM/IV every 4-6 h as needed |

|

Parkinsonism |

– Tremor – Bradykinesia – Rigidity – Flat affect |

– Benztropine 1-4 mg PO bid; or – Diphenhydramine 25 mg PO bid – Consider switching first-generation antipsychotic to second-generation or lower-potency antipsychotic |

|

Akathisia |

– Restlessness (lower extremities) – Pacing – Inability to stand still – Rocking from foot to foot |

– Decrease dose of antipsychotic – Consider switching antipsychotic – Propranolol 10-80 mg PO daily or in divided doses – Consider clonazepam 0.5 mg PO daily for short duration |

|

Tardive dyskinesia |

Nonrhythmic and quick movements: – Oral-buccal muscles – Tongue – Pharynx – Trunk – Diaphragm |

– Consider preventative measures – Switch to clozapine may decrease movements – Valbenazine 40-80 mg PO daily; or – Deutetrabenazine 6-24 mg PO bid |

|

bid, 2 times a day; EPS, extrapyramidal symptom; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; PO, oral; tid, 3 times a day. | ||

|

High potency |

Medium potency |

Low potency |

|

– Trifluoperazine – Thiothixene – Fluphenazine – Haloperidol |

– Loxapine – Perphenazine

|

– Chlorpromazine – Methotrimeprazine |

|

Mechanism |

Agents |

|

Decreased serotonin breakdown |

– MAOIs – Antibiotics: linezolid, tedizolid – Procarbazine |

|

Decreased serotonin reuptake |

– SSRIs: fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline – SNRIs: venlafaxine, duloxetine, milnacipran – TCAs: clomipramine, imipramine, amitriptyline – Herbal: St John’s wort – Opioids: meperidine (INN pethidine), buprenorphine, tramadol, tapentadol, dextromethorphan – Antiepileptics/mood stabilizers: valproate, carbamazepine – Antiemetics: ondansetron, metoclopramide |

|

Increased serotonin precursors and agonists |

– Tryptophan – Lithium carbonate – Fentanyl – LSD |

|

Increased serotonin release |

– Amphetamines – Cocaine – MDMA |

|

Drug-drug interactions |

– Inhibitors of CYP2D6 – Inhibitors of CYP3A4 – Antibiotics: erythromycin, ciprofloxacin – Antifungal: fluconazole – Antiretroviral: ritonavir |

|

LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant. |

|

Figure 16.2-1. Clinical features of mild, moderate, and severe forms of serotonin syndrome.

Figure 16.2-2. Features of neuroleptic malignant syndrome.