Thurtell MJ. Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019 Oct;25(5):1289-1309. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000770. PMID: 31584538.

Mollan SP, Davies B, Silver NC, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: consensus guidelines on management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Oct;89(10):1088-1100. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317440. Epub 2018 Jun 14. PMID: 29903905; PMCID: PMC6166610.

ten Hove MW, Friedman DI, Patel AD, Irrcher I, Wall M, McDermott MP; NORDIC Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Study Group. Safety and Tolerability of Acetazolamide in the Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial. J Neuroophthalmol. 2016 Mar;36(1):13-9. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000322. PMID: 26587993.

Friedman DI, Liu GT, Digre KB. Revised diagnostic criteria for the pseudotumor cerebri syndrome in adults and children. Neurology. 2013 Sep 24;81(13):1159-65. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a55f17. Epub 2013 Aug 21. PMID: 23966248.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a syndrome characterized by symptoms and signs of increased intracranial pressure of unknown etiology. Patients with IIH have elevated lumbar puncture opening pressure with normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) composition in the absence of a mass lesion, hydrocephalus, abnormal meningeal enhancement, and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis on neuroimaging. Women with obesity in the childbearing years represent 90% of cases. Other well-known associations include recent weight gain, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and cerebral venous sinus stenosis. However, the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism remains unclear.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

1. Symptoms: Headache is the most common symptom, and the phenotype is highly variable. It often mimics primary headache disorders, such as migraine or tension-type headache. Patients frequently complain of unilateral or bilateral pulse-synchronous tinnitus. Episodes of transient partial or complete vision loss lasting seconds with full recovery, known as transient visual obscurations, are common. Diplopia, characteristically binocular and horizontal, can occasionally be reported.

The most important consequence of this condition is vision loss, which occurs in most patients and whose severity varies, with ~10% of patients developing bilateral blindness. Given the risk of vision loss and the decreased quality of life from its symptoms, the term “benign” intracranial hypertension is completely inappropriate.

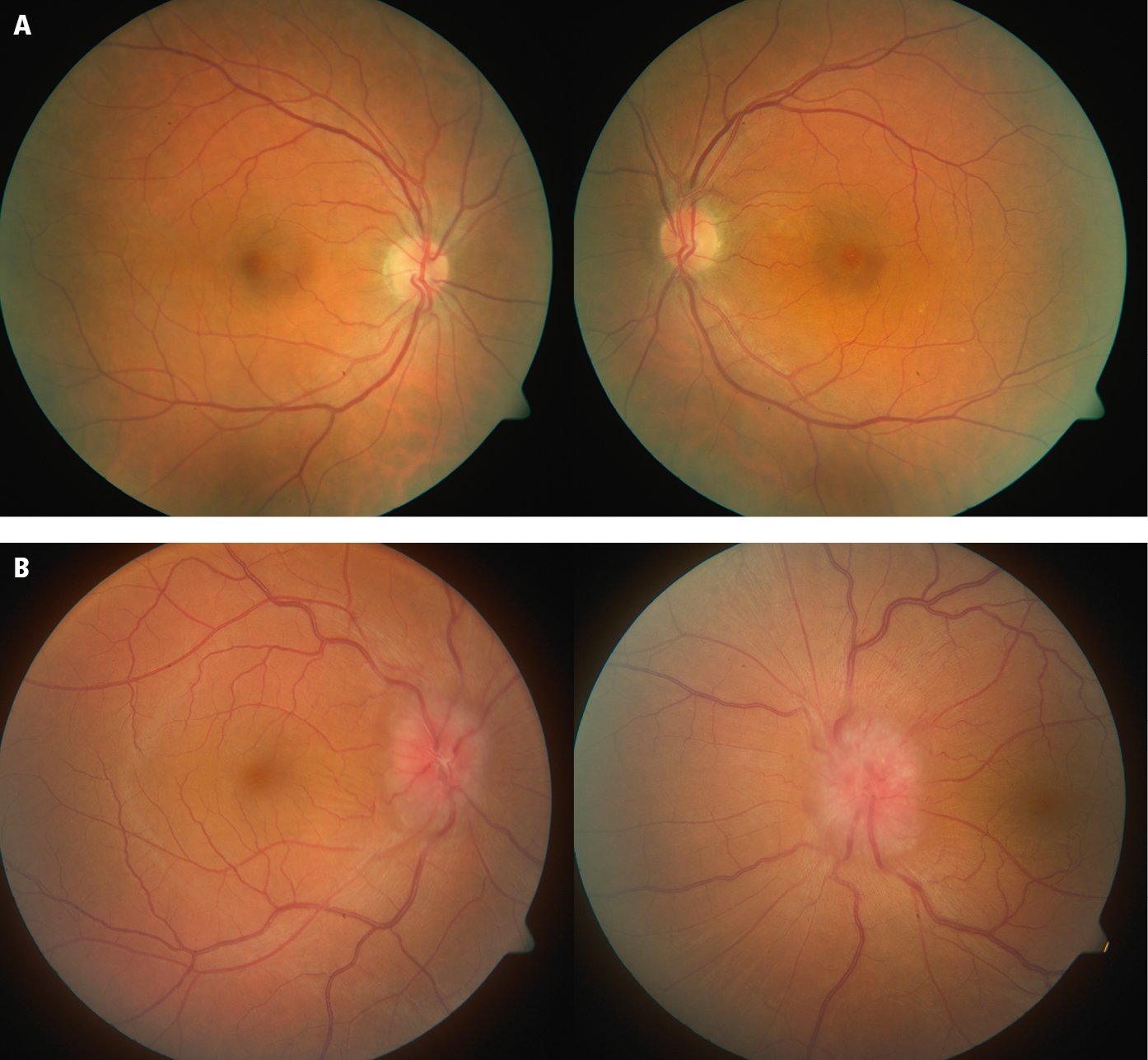

2. Signs: The most important sign is papilledema (Figure 12.1-1), defined as optic disc edema secondary to increased intracranial pressure. Characteristically, it is bilateral, although it can be asymmetric and, rarely, unilateral. A minority of patients may present without papilledema (Table 12.1-1). Unilateral or bilateral abducens nerve (sixth cranial nerve) palsy is another possible finding. Otherwise, neurologic examination is normal and patients must be oriented and alert, as encephalopathy should suggest an alternative diagnosis.

3. Red flags: Optimally, all patients with headaches should have an ophthalmoscopic evaluation, in particular when there is new onset or change of previous headaches, increasing severity, pulsatile tinnitus, or visual changes. When these symptoms occur in young patients with overweight, IIH should be considered in the differential diagnosis. If optic disc edema is present, urgent neuroimaging and referral to ophthalmology, neurology, or both is warranted.

DiagnosisTop

Diagnosis is based on symptoms and signs of raised intracranial pressure in an alert and awake patient, with normal neuroimaging and CSF analysis results except for elevated lumbar opening pressure, in accordance with the diagnostic criteria (Table 12.1-1).

1. Neuroimaging studies: In any patient with suspected intracranial hypertension, emergent neuroimaging should be obtained. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with contrast including magnetic resonance venography (MRV) is the modality of choice, as it allows identification of most structural causes of raised intracranial pressure. MRV should be obtained at the same time as MRI to specifically exclude cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

2. Lumbar puncture/CSF evaluation: Lumbar puncture confirms the presence of increased opening pressure. In addition, the evaluation of CSF constituents is useful to exclude secondary causes of increased intracranial pressure.

3. Ophthalmic investigations: A formal visual field examination is mandatory for the evaluation and monitoring of patients with IIH. Visual field loss occurs in most patients with IIH, but it is often unnoticed unless formal perimetry is obtained. Treatment decisions are frequently made based on changes in visual field function.

Evaluation of visual acuity alone is inappropriate, as it is a late development in the course of IIH, usually when there has already been marked peripheral vision loss.

Papilledema is the hallmark of this condition and thus fundoscopy is necessary to evaluate the optic nerve head (Figure 12.1-1). Documentation of the optic nerve appearance as part of the optic nerve evaluation can be done with serial fundus photos or optical coherence tomography (OCT).

Secondary causes of intracranial hypertension should be excluded. Several agents can induce a clinical syndrome that mimics IIH, including lithium, tetracycline antibiotics, vitamin A derivatives, and glucocorticoid withdrawal, among others. Conditions leading to cerebral venous hypertension, such as cerebral venous sinus thrombosis or arteriovenous fistula, should be excluded.

TreatmentTop

Treatment is aimed at alleviating symptoms and preserving visual function.

All patients should be counseled about weight management.Evidence 1Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the observational nature of studies but increased due to large effect size. Subramaniam S, Fletcher WA. Obesity and Weight Loss in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension: A Narrative Review. J Neuroophthalmol. 2017 Jun;37(2):197-205. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000448. PMID: 27636748. Sinclair AJ, Burdon MA, Nightingale PG, et al. Low energy diet and intracranial pressure in women with idiopathic intracranial hypertension: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2010 Jul 7;341:c2701. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2701. PMID: 20610512; PMCID: PMC2898925. A loss of 5% to 10% of initial body weight is often enough to induce remission in most patients with IIH.Evidence 2Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the observational nature of data and effect size. Subramaniam S, Fletcher WA. Obesity and Weight Loss in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension: A Narrative Review. J Neuroophthalmol. 2017 Jun;37(2):197-205. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000448. PMID: 27636748. Sinclair AJ, Burdon MA, Nightingale PG, et al. Low energy diet and intracranial pressure in women with idiopathic intracranial hypertension: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2010 Jul 7;341:c2701. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2701. PMID: 20610512; PMCID: PMC2898925.

Acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, decreases the production of CSF and is the main medical treatment for IIH, especially in those in whom weight loss is ineffective or not achieved. It is usually prescribed at an initial dose of 250 or 500 mg bid and can be titrated up as tolerated to a maximum dose of 4000 mg daily.Evidence 3Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision and indirectness. NORDIC Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Study Group Writing Committee, Wall M, McDermott MP, Kieburtz KD, et al. Effect of acetazolamide on visual function in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension and mild visual loss: the idiopathic intracranial hypertension treatment trial. JAMA. 2014 Apr 23-30;311(16):1641-51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3312. PMID: 24756514; PMCID: PMC4362615. In patients with mild visual field loss, (defined by and for ophthalmologists as a perimetric mean deviation of −2 dB to −7dB), it has been shown to improve visual field function, papilledema severity, and quality of life measures. It can also be used for patients with more severe visual field loss, in particular while surgical intervention is being considered.

Of note, use of acetazolamide may be associated with several adverse effects such as metabolic acidosis, aplastic anemia, paresthesias, dysgeusia, gastrointestinal symptoms, and kidney stones. It should be avoided in pregnancy and patients should be cautioned about the potential teratogenic risk. The Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial (IIHTT) has shown that dosages up to 4 g daily are safe, although a large number of patients are not able to tolerate such a high dose. Even though periodic monitoring of serum electrolytes is often recommended, there is no consensus on how frequently it should be done. In the IIHTT, electrolytes were checked at baseline; every 2 weeks during dosage escalation; and at 1, 3, and 6 months. Monitoring of blood count and liver enzymes should also be considered.

Topiramate is frequently used to treat primary headache disorders, has a weak carbonic anhydrase inhibitor activity, and induces weight loss. For these reasons it is useful for the management of headaches in patients with IIH. Common adverse effects include depression, cognitive slowing, decreased appetite, kidney stones, and acute angle closure glaucoma. It should not be used during pregnancy.

Surgery should be considered in patients with evidence of declining visual function and imminent risk of vision loss. The surgical intervention of choice often depends on local resources and availability. Interventions fall within 3 categories:

1) CSF diversion procedures: Very useful to rapidly decrease intracranial pressure. Ventriculoperitoneal shunts are usually preferred over lumboperitoneal shunts.

2) Optic nerve sheath fenestration (ONSF): Opening a window in the retrobulbar optic nerve sheath.

3) Transverse venous sinus stenting: Its role in IIH is not yet fully established. It may be useful in selected patients.

Follow-UpTop

Management of an individual patient depends on the severity of vision loss as determined by formal perimetry, degree of papilledema, and severity of headaches.

Because visual acuity loss is a late finding, formal visual field testing is the most critical test to monitor visual function in patients with IIH. While an initial lumbar puncture is required to fulfill the diagnostic criteria, most clinicians do not use repeat lumbar punctures as a way to monitor intracranial pressure and response to treatment. Instead, papilledema as measured clinically using fundus photography, OCT, or both is a useful surrogate for average CSF pressure. Given the importance of obesity and weight changes in this condition, body-mass index (BMI) should be recorded. Headache phenotype is variable and may change over time.

PrognosisTop

IIH is a chronic disease and patients need long-term monitoring. Recurrences are often due to weight gain and thus it is important to emphasize the need to achieve and sustain weight loss. Most patients with IIH have some degree of visual field loss on formal perimetry, which represents the major morbidity of this condition.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

1. Papilledema 2. Normal neurologic examination except for sixth nerve palsy 3. Normal brain parenchyma with no hydrocephalus, mass, structural lesion, or abnormal meningeal enhancement on MRI; venous imaging needed to exclude cerebral venous sinus thrombosis 4. Normal CSF analysis 5. Elevated lumbar puncture opening pressure ≥25 cm CSF |

|

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension without papilledema can be diagnosed if criteria 2-5 are met and the patient has unilateral or bilateral cranial nerve sixth palsy. |

|

In the absence of papilledema or sixth nerve palsy, idiopathic intracranial hypertension without papilledema can be suggested but not confirmed if criteria 2-5 are satisfied and there are ≥3 neuroimaging findings suggestive of increased intracranial pressure: 1) Empty sella 2) Flattening of the posterior aspect of the globe 3) Distension of the perioptic subarachnoid space with or without optic nerve tortuosity 4) Transverse venous sinus stenosis |

|

Based on Neurology. 2013 Sep 24;81(13):1159-65. |

|

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. |

Figure 12.1-1. A, normal looking optic discs. B, bilateral papilledema.