Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 1;200(7):e45-e67. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST. PMID: 31573350; PMCID: PMC6812437.

National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Pneumonia: Diagnosis and Management of Community- and Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2014 Dec. PMID: 25520986.

Woodhead M, Blasi F, Ewig S, et al; Joint Taskforce of the European Respiratory Society and European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections--summary. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011 Nov;17 Suppl 6:1-24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03602.x. PMID: 21951384.

Limper AH, Knox KS, Sarosi GA, et al; American Thoracic Society Fungal Working Group. An official American Thoracic Society statement: Treatment of fungal infections in adult pulmonary and critical care patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Jan 1;183(1):96-128. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2008-740ST. PMID: 21193785.

Lim WS, Baudouin SV, George RC, et al; Pneumonia Guidelines Committee of the BTS Standards of Care Committee. BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax. 2009 Oct;64 Suppl 3:iii1-55. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.121434. PMID: 19783532.

Torres A, Ewig S, Lode H, Carlet J; European HAP working group. Defining, treating and preventing hospital acquired pneumonia: European perspective. Intensive Care Med. 2009 Jan;35(1):9-29. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1336-9. PMID: 18989656.

American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005 Feb 15;171(4):388-416. PMID: 15699079.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is characterized by signs and symptoms of an acute lower respiratory tract infection and new-onset opacities observed on chest radiographs that cannot be explained otherwise (eg, by pulmonary edema or pulmonary infarct). For the purposes of this chapter, this definition does not apply to patients with cancer; immunocompromised individuals; persons hospitalized for pneumonia in oncology, hematology, palliative care, infectious diseases, or AIDS units; patients living in long-term care institutions; and patients hospitalized within the prior 14 days.

Etiologic agents: CAP can be caused by a large number of microbial species but most frequently by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. In a large number of patients there may be dual infections, particularly where viruses (such as influenza) predispose to superinfection with bacteria such as S pneumoniae or Staphylococcus aureus. Pathogens may reach the lower respiratory tract as a result of microaspiration of upper respiratory tract secretions, aspiration of oral and upper respiratory tract secretions, inhalation of large infectious respiratory particles (historically droplets) produced by a coughing patient with viral infection, inhalation of a water aerosol containing Legionella organisms, or exposure to droplet nuclei, such as tuberculosis. Pneumonia may also be caused by fungi, viruses other than influenza or parainfluenza, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), or mycobacteria, which depend on epidemiologic exposure and host factors.

Pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection (coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19]) is described separately (see Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)) but may need to be taken into account while evaluating and empirically treating patients with CAP.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

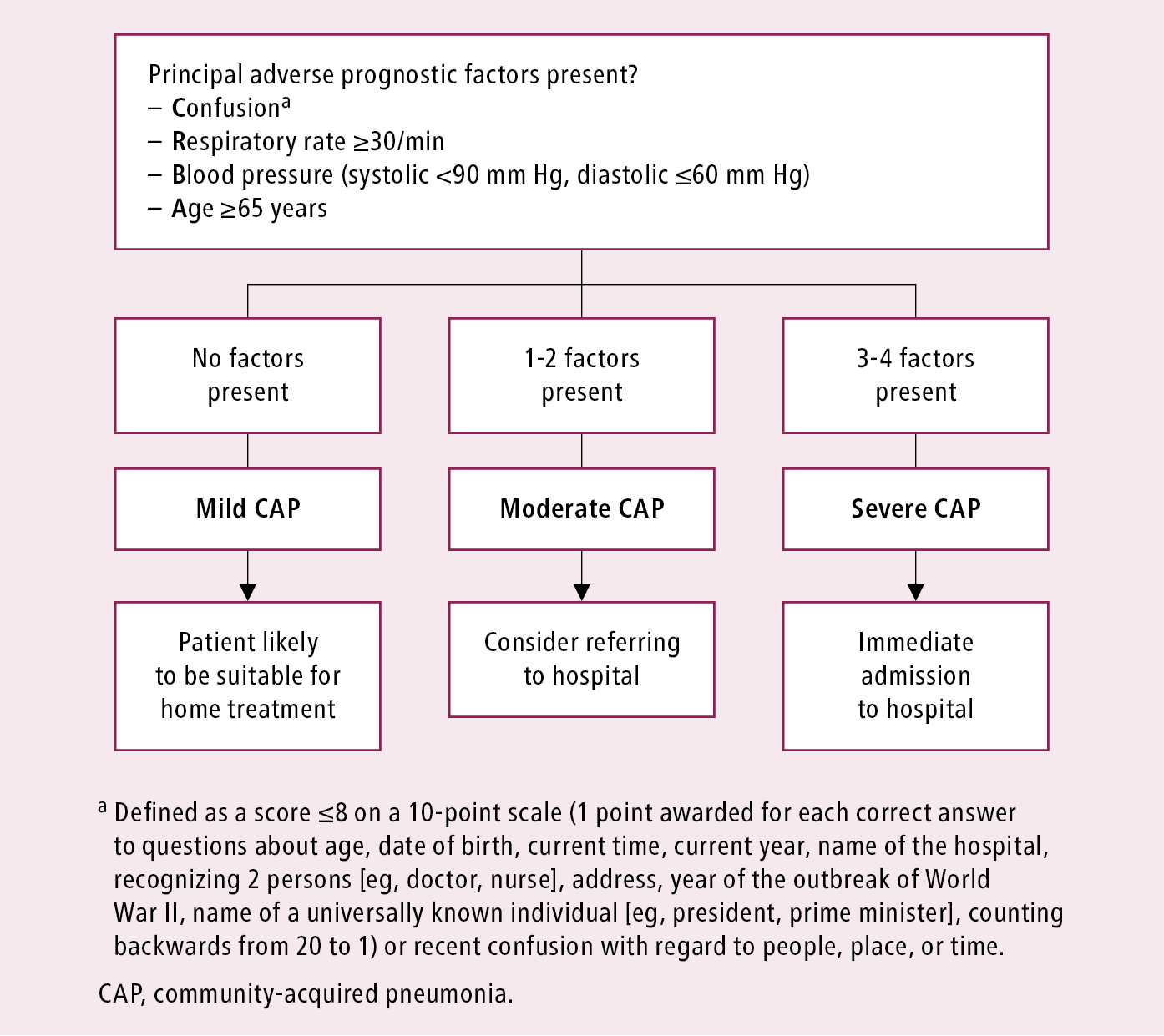

1. Symptoms typically have an acute onset and include fever, chills and sweating, pleuritic chest pain, cough with or without the production of purulent sputum, and dyspnea (in some patients). Older adults with CAP are more likely to have nonspecific symptoms, may not develop fever, and may develop confusion (see Figure 17.17-1).

2. Signs: Tachypnea, tachycardia, dull percussion over the area of inflammatory infiltrate, crackles, increased tactile fremitus, and sometimes bronchial breath sounds. In patients with pleural effusion, dull percussion, absence of tactile fremitus, and poorly audible breath sounds are observed.

3. Natural history depends mainly on the patient’s age, comorbidities, and the etiologic factor. Pneumonia caused by staphylococci, Legionella, and anaerobic bacteria is generally more severe than pneumococcal and mycoplasmal inflammation.

DiagnosisTop

In patients treated on an outpatient basis or prior to hospitalization (in whom no laboratory test or radiologic results are available), the diagnosis of pneumonia is based on the following:

1) Signs and symptoms of acute lower respiratory tract infection: Cough and ≥1 additional manifestation of lower respiratory tract infection, such as dyspnea, pleuritic pain, or hemoptysis.

2) New local findings on examination of the chest.

3) One or more of the general signs and symptoms: Sweats, chills, myalgia, temperature ≥38 degrees Celsius.

4) No other explanations for the observed manifestations.

Assessment of Disease Severity

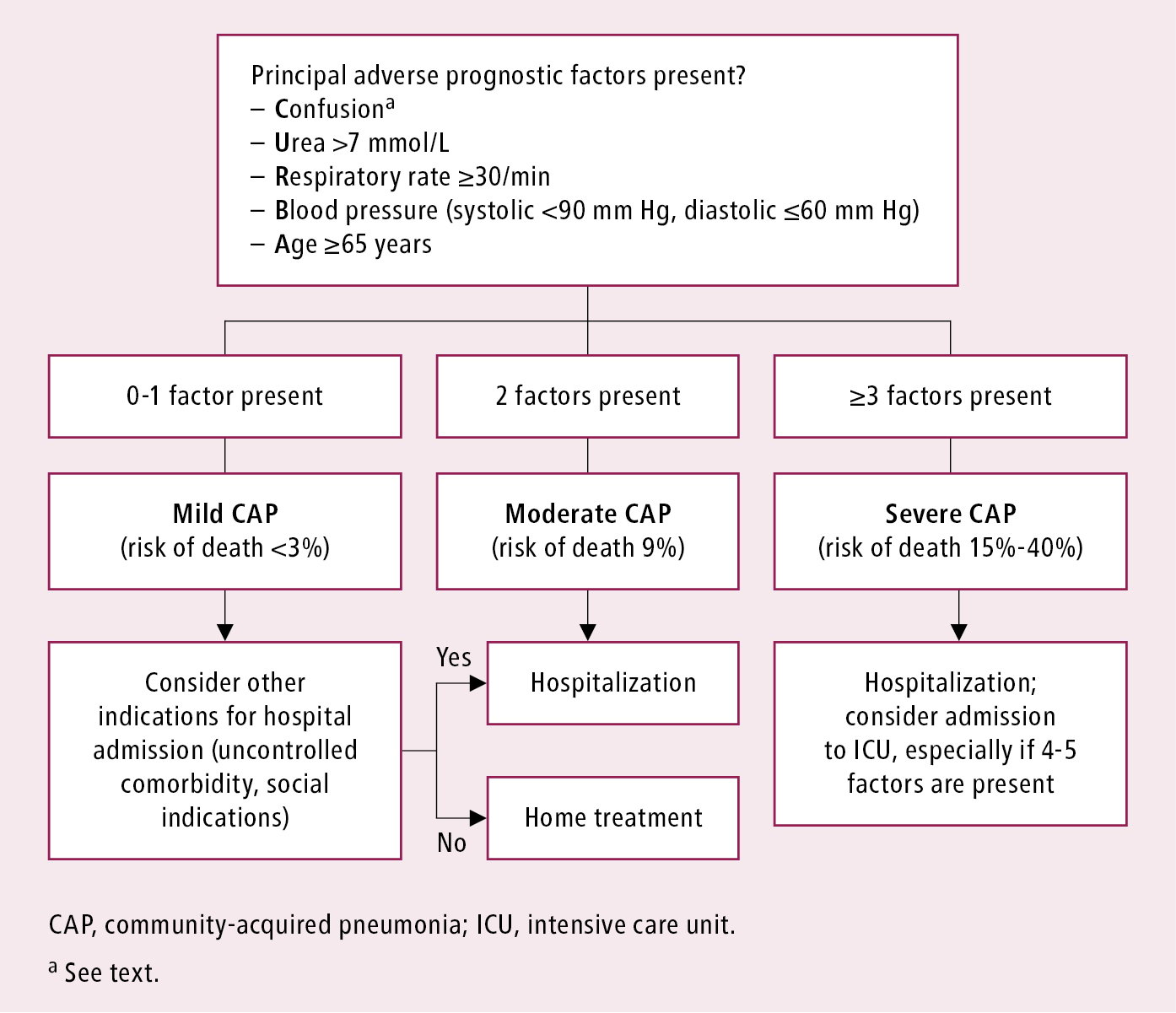

To decide on an outpatient or inpatient treatment setting, use the CRB-65 score (Figure 17.17-1) in outpatients and the CURB-65 score (Figure 17.17-2) in hospitalized patients. Pulse oximetry can be considered in settings where emergency oxygen is used.

Presence of ≥3 of the following criteria is also indicative of severe pneumonia: respiratory rate >30 breaths/min; partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood/fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) ratio <250; presence of multilobar infiltrates; confusion/disorientation; blood urea nitrogen level >7 mmol/L (20 mg/dL); white blood cell count <4000 cells/mL; platelet count <100,000/mL; core temperature <36.8 degrees Celsius; hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation.

1. Studies to be performed in every patient on admission:

1) Chest radiography: Results reveal new infiltrates. There are no strong correlations between specific radiographic patterns and etiologic agents. Although ultrasonography and especially computed tomography (CT) of the chest may provide additional, more precise information about the extent and nature of the infiltrates or presence of pleural effusion, they are rarely needed.

2) Complete blood count (CBC) and differential blood count: Leukocytosis with predominant neutrophils may be suggestive of a bacterial etiology.

3) Serum levels of urea, electrolytes, bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine aminotransferase may be used to help determine the severity of the systemic disease.

4) Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (levels <20 mg/L suggest against the diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia; the increase is more pronounced in pneumococcal pneumonia with concomitant bacteremia than in pneumonia caused by viruses or Mycoplasma spp) or procalcitonin levels (should not be used to determine the need for initial therapy; may be helpful in making the decision to discontinue antibiotics following treatment).

5) Measurement of blood oxygen levels: Pulse oximetry (hypoxemia may be observed). In patients at risk or with clinical suspicion of hypercapnia (individuals with hypoxia, history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], respiratory effort, severe pneumonia), measure arterial blood gas levels, if available.

6) Microbiology: Collect 2 sets of blood cultures and sputum specimens for culture in patients with moderate or severe CAP prior to starting antimicrobial therapy, if possible. In particular, collect these for inpatients with severe disease and for those empirically treated for or at high risk of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection (in the case of prior respiratory isolation of MRSA or P aeruginosa or recent hospitalization and receipt of parenteral antibiotics in the previous 90 days). In those with severe CAP also collect urine to test for S pneumoniae antigen and Legionella antigen (serogroup 1 only; also in cases of suspected legionellosis).

2. Other studies to be performed depending on the clinical manifestations:

1) Serologic studies may be performed in patients with severe CAP and where other diagnostic tests have failed to provide an etiology. This is particularly important for patients who have failed to improve or in the setting of an outbreak. Infection is usually indicated by a 4-fold increase in serum IgG levels at an ~3-week interval.

2) Bronchoscopy may be performed to collect samples for testing and is used as part of differential diagnosis (in patients with suspected bronchial obstruction/stenosis, lung cancer, aspiration, or patients with recurrent pneumonia) as well as to evacuate respiratory secretions from the airway.

3) Thoracentesis as well as biochemical, cytologic, and microbiologic examination of pleural effusion are performed when indicated (in patients with parapneumonic effusion).

4) Rarely: Transthoracic or transbronchial biopsy of the affected part of the lung with microbiologic and cytologic/pathomorphologic testing.

Differential diagnosis includes lung cancer, tuberculosis, pulmonary embolism, eosinophilic pneumonia, acute interstitial pneumonia, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, lung involvement in collagen tissue diseases, and systemic vasculitis.

Lack of efficacy of the initial empiric treatment is an indication for an intense diagnostic workup in search for the etiologic factor and for a repeated differential diagnosis.

TreatmentTop

1. Outpatient treatment: Smoking cessation, rest, drinking large quantities of fluids. Use acetaminophen (INN paracetamol) to control fever and pleuritic pain when present. Pulse oximetry may be useful for assessment of severity and oxygen requirement.

2. Hospital treatment:

1) Oxygen therapy with SpO2 monitoring (in patients with COPD, consider repeated arterial or venous blood gas measurements) with a target partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) ≥60 mm Hg and SpO2 92% to 96% (88%-92% in patients with COPD and patients at risk of hypercapnia). If hypoxemia persists in spite of high-concentration oxygen therapy, consider high-flow oxygen therapy or mechanical ventilation.

2) Assess volume status and nutrition. Administer fluids and start nutrition therapy when indicated.

3) We suggest oral prednisone (50 mg once daily for 1 week), particularly in patients with CRP >150 mg/L, patients requiring mechanical ventilation, or patients with septic shock.Evidence 1Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision. Siemieniuk RA, Meade MO, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Corticosteroid Therapy for Patients Hospitalized With Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Oct 6;163(7):519-28. doi: 10.7326/M15-0715. Review. PMID: 26258555. Briel M, Spoorenberg SMC, Snijders D, et al; Ovidius Study Group; Capisce Study Group; STEP Study Group. Corticosteroids in Patients Hospitalized With Community-Acquired Pneumonia: Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Metaanalysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Jan 18;66(3):346-354. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix801. PMID: 29020323. Of note, the use of glucocorticoids is not recommended in the recent Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society (IDSA/ATS) guidelines in the absence of shock or glucocorticoid-requiring comorbid conditions.

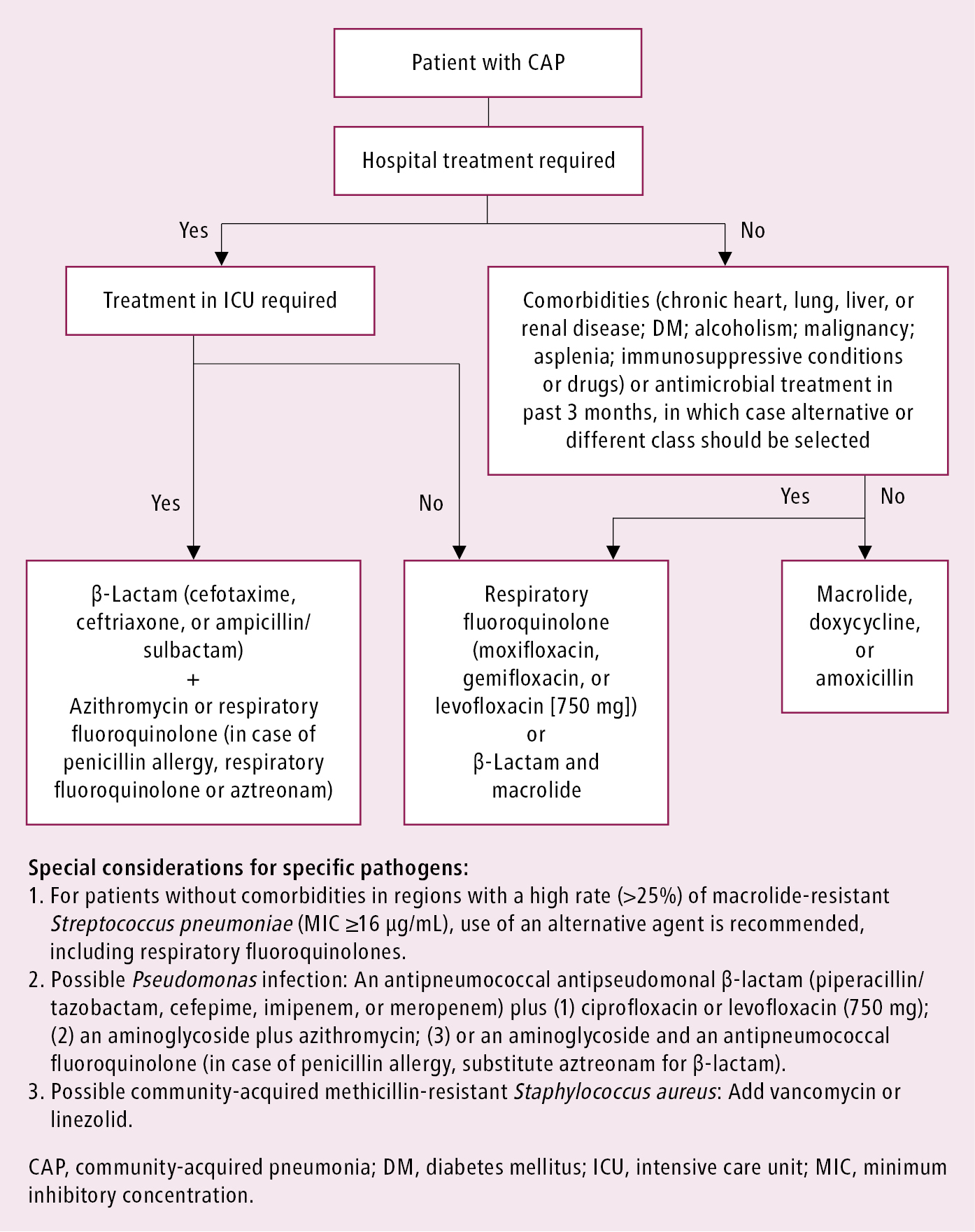

1. In patients who are referred to hospital with suspected CAP, consider starting antimicrobial treatment immediately in the case of severe illness or a risk of delay in reaching the hospital (>2 h). In hospitalized patients, start antibiotic treatment as soon as possible after the diagnosis is established.

2. Choice of antimicrobial agents: Initial empiric treatment: Figure 17.17-3; if the etiologic agent is known: Table 17.17-1. In hospitalized patients switch from IV to oral antibiotic when the patients are hemodynamically stable, improving clinically, and able to ingest medications. It should be noted that European recommendations differ from current North American guidelines, as amoxicillin is the first-line therapy for mild CAP while ampicillin or penicillin IV and a macrolide is recommended for hospitalized cases, while amoxicillin and clavulanic acid and a macrolide are recommended for severe hospitalized cases.

3. Duration of treatment: In outpatients and the majority of hospitalized patients treatment is continued for a minimum of 5 days. The patient should be afebrile for 48 to 72 hours prior to discontinuing antibiotics. Key considerations are normalization of vital signs and oxygen saturation, return to normal mental status, and ability to maintain oral intake. Longer treatment should be considered if the expected improvement in symptoms does not occur during the first 3 days; in patients with severe CAP of undetermined etiology, it is continued for 10 days; and in patients with CAP caused by Legionella pneumophila, staphylococci, P aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, or gram-negative intestinal bacilli, up to 14 to 21 days.

Follow-UpTop

1. Outpatients: Perform a follow-up examination after at most 48 hours. If no clinical improvement is observed, consider referring the patient for chest radiography and other diagnostic studies.

2. Hospitalized patients:

1) Monitor temperature, respiratory rate, pulse, blood pressure, mental status, and SaO2. Initially perform these assessments at least twice a day, or more often in patients with severe pneumonia. In patients who receive an appropriate antibiotic, improvement should be observed within 24 to 48 hours.

2) In patients with clinical improvement, do not repeat chest radiographs prior to discharge. If the improvement has not been satisfactory, repeat chest radiographs.

3) If the initial empiric treatment has not been effective, make intensive efforts to identify the antibiotic-resistant pathogens and repeat differential diagnosis.

4) Do not discharge patients who fulfill ≥2 of the following criteria during the prior 24 hours: temperature >37.5 degrees Celsius, respiratory rates ≥24/min, heart rates >100/min, systolic blood pressure ≤90 mm Hg, SpO2 <90% (while on air), abnormal mental status, inability to eat without assistance. Consider a delayed discharge in individuals with any of those criteria present.

5) In every patient schedule a follow-up visit within ~6 weeks. Chest radiographs should be repeated in all patients with persisting signs and symptoms and patients at a higher risk of developing cancer (particularly tobacco smokers and patients >50 years). Radiographic abnormalities, especially when extensive, resolve less rapidly than clinical features (typically within 4-8 weeks), particularly in older individuals. If radiologic or clinical abnormalities persist after 6 weeks or recur in the same location, perform bronchoscopy.

ComplicationsTop

1. Pleural effusion and empyema (see Exudative Pleural Effusion).

2. Lung abscess: A purulent collection located in the pulmonary parenchyma that most frequently develops as a consequence of pneumonia caused by staphylococci, anaerobic bacteria, Klebsiella pneumoniae, or P aeruginosa. A CT scan provides more detailed information than a chest radiograph.

Signs and symptoms are the same as in pneumonia. Diagnosis is based on radiologic findings revealing an interstitial cavity with an air-fluid level.

Treatment: Antimicrobial agents and postural drainage. In rare cases not responding to treatment, surgical resection is used. As an initial empiric treatment, IV penicillin G (INN benzylpenicillin) 1.8 to 2.7 g (3-4.5 million IU) qid in combination with IV metronidazole 0.5 g qid can be used; IV clindamycin 600 mg qid; or IV amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 1.2 g tid to qid. If the etiologic agent and its resistance pattern are known, start targeted treatment. Treatment should be continued until the abscess cavity closes (usually within a few weeks).

Special ConsiderationsTop

Pneumonia in Immunocompromised Patients

Diagnosis: This group of patients is particularly vulnerable to infections with mycobacteria, fungi (Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans, Pneumocystis jiroveci), and viruses. The etiologic organism will differ depending on both host characteristics (specific immunologic defect) and epidemiologic exposures. Generally, diagnostic evaluations may include microscopic evaluation of sputum (this may help with the diagnosis of pneumocystosis and tuberculosis), sputum cultures, blood cultures, bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage, CT (eg, aspergillosis), or alternatively transbronchial lung biopsy specimens. Surgical lung biopsy may also be needed for some cases. Empiric treatment should take into account the probability of infections with MRSA, Pseudomonas, and Legionella.

Treatment: Start treatment empirically, that is, prior to confirming microbiologic etiology, based on the nature of the immunocompromised state and knowledge of exposures. Prompt infectious diseases consultation is warranted.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Organism |

Preferred antimicrobials |

Alternative antimicrobials |

|

Streptococcus pneumoniae |

||

|

Penicillin nonresistant; MIC <2 microg/mL |

Penicillin G, amoxicillin |

Macrolide, cephalosporins (oral [cefpodoxime, cefprozil, cefuroxime, cefdinir, cefditoren] or parenteral [cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime]), clindamycin, doxycycline, respiratory fluoroquinolonea |

|

Penicillin resistant; MIC ≥2 microg/mL |

Agents chosen on the basis of susceptibility, including cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, fluoroquinolone |

Vancomycin, linezolid, high-dose amoxicillin (3 g/d with penicillin MIC ≤4 microg/mL) |

|

Haemophilus influenzae |

||

|

Non–beta-lactamase producing |

Amoxicillin |

Fluoroquinolone, doxycycline, azithromycin, clarithromycinb |

|

Beta-lactamase producing |

Second- or third-generation cephalosporin, amoxicillin/clavulanate |

Fluoroquinolone, doxycycline, azithromycin, clarithromycinb |

|

Mycoplasma pneumoniae/Chlamydophila pneumoniae |

Macrolide, a tetracycline |

Fluoroquinolone |

|

Legionella spp |

Fluoroquinolone, azithromycin |

Doxycycline |

|

Chlamydophila psittaci |

A tetracycline |

Macrolide |

|

Coxiella burnetii |

A tetracycline |

Macrolide |

|

Francisella tularensis |

Doxycycline |

Gentamicin, streptomycin |

|

Yersinia pestis |

Streptomycin, gentamicin |

Doxycycline, fluoroquinolone |

|

Bacillus anthracis (inhalation) |

Ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, doxycycline (usually with a second agent) |

Other fluoroquinolones; beta-lactam, if susceptible; rifampin; clindamycin; chloramphenicol |

|

Enterobacteriaceae |

Third-generation cephalosporin, carbapenemc (drug of choice if extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producer) |

Beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor,d fluoroquinolone |

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

Antipseudomonal beta-lactame plus (ciprofloxacin or levofloxacinf or aminoglycoside) |

Aminoglycoside plus (ciprofloxacin or levofloxacinf) |

|

Burkholderia pseudomallei |

Carbapenem, ceftazidime |

Fluoroquinolone, TMP/SMX |

|

Acinetobacter spp |

Carbapenem |

Cephalosporin-aminoglycoside, ampicillin/sulbactam, colistin |

|

Staphylococcus aureus |

||

|

Methicillin susceptible |

Antistaphylococcal penicilling |

Cefazolin, clindamycin |

|

Methicillin resistant |

Vancomycin or linezolid |

TMP/SMX |

|

Bordetella pertussis |

Macrolide |

TMP/SMX |

|

Anaerobe (aspiration) |

Beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor,d clindamycin |

Carbapenem |

|

Influenza virus |

Oseltamivir or zanamivir |

|

|

Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

Isoniazid plus rifampin plus ethambutol plus pyrazinamide |

|

|

Coccidioides spp |

For uncomplicated infection in a normal host, no therapy generally recommended; for therapy, itraconazole, fluconazole |

Amphotericin B |

|

Histoplasmosis |

Itraconazole |

Amphotericin B |

|

Blastomycosis |

Itraconazole |

Amphotericin B |

|

Choices should be modified on the basis of susceptibility test results and advice from local specialists. Refer to local references for appropriate doses. |

||

|

a Levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gemifloxacin (not a first-line choice for penicillin susceptible strains); ciprofloxacin is appropriate for Legionella and most gram-negative bacilli (including Haemophilus influenzae). b Azithromycin is more active in vitro than clarithromycin for H influenzae. c Imipenem/cilastatin, meropenem, ertapenem. d Piperacillin/tazobactam for gram-negative bacilli, ticarcillin/clavulanate, ampicillin/sulbactam, or amoxicillin/clavulanate. e Ticarcillin, piperacillin, ceftazidime, cefepime, aztreonam, imipenem, meropenem. f 750 mg daily. g Nafcillin, oxacillin, flucloxacillin. |

||

|

INN, international nonproprietary name; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. |

||

Figure 17.17-1. Severity assessment of community-acquired pneumonia in the outpatient setting: CRB-65 Score. Adapted from the 2009 British Thoracic Society guidelines.

Figure 17.17-2. Severity assessment of community-acquired pneumonia in the inpatient setting: CURB-65 Score. Adapted from the 2009 British Thoracic Society guidelines.

Figure 17.17-3. Recommended empiric antibiotics in community-acquired pneumonia. Adapted from Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Mar 1;44 Suppl 2:S27-72 and Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 1;200(7):e45-e67.