Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, et al; American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin American Thoracic Society. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Sep 1;198(5):e44-e68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST. PubMed PMID: 30168753.

Lynch DA, Sverzellati N, Travis WD, et al. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a Fleischner Society White Paper. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Feb;6(2):138-153. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30433-2. Epub 2017 Nov 15. Review. PubMed PMID: 29154106.

Collard HR, Ryerson CJ, Corte TJ, et al. Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An International Working Group Report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Aug 1;194(3):265-75. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0801CI. Review. PubMed PMID: 27299520.

Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y, et al; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory society; Japanese Respiratory Society; Latin American Thoracic Association. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Update of the 2011 Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Jul 15;192(2):e3-19. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1063ST. Erratum in: Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Sep 1;192(5):644. Dosage error in article text. PubMed PMID: 26177183.

Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al; ATS/ERS Committee on Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Sep 15;188(6):733-48. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST. PubMed PMID: 24032382.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most common form of chronic progressive fibrosing interstitial pneumonia of unknown cause, occurring primarily in older adults aged >60 years and limited to the lungs. Defined by a distinct radiographic and histologic pattern called usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), IPF is characterized by a relentless progression of interstitial fibrosis and a progressive decline in gas exchange. The median survival from the time of diagnosis is approximately 3 to 5 years.

The incidence of disease increases with older age, with presentation typically occurring in the sixth and seventh decades of life. Cohort studies have shown that the majority of patients have a history of cigarette smoking and more men than women are affected.

A genetic predisposition is observed in 2% to 20% of patients. Hereditary disease is typically inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with incomplete penetrance. Mutations in the promoter region of MUC5B and genes associated with telomere maintenance and surfactant protein expression have been among the various genetic abnormalities reported. The precise genetic and host susceptibility factors that determine the phenotypic expression and clinical manifestations of sporadic IPF remain unknown.

Clinical FeaturesTop

IPF has an insidious onset and manifests as unexplained exertional dyspnea and dry cough, which progress over many months to years. Patients commonly have bibasilar crackles on chest auscultation, with nearly 25% of patients demonstrating evidence of clubbing. In later stages IPF patients can develop symptoms of cor pulmonale with progressive right ventricular dysfunction.

DiagnosisTop

The radiographic and histologic UIP pattern can be observed in numerous fibrotic interstitial lung diseases (ILDs), including asbestosis, connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD), chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and drug reactions. Hence, as proposed by the updated consensus statement on IPF, the establishment of a diagnosis of IPF requires:

1) Exclusion of other known causes of ILD (eg, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, occupational environmental exposures, connective tissue diseases, and adverse drug reactions).

2) Confirmation of typical features of UIP on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) in patients not subjected to surgical lung biopsy.

3) Specific combinations of HRCT and histologic abnormalities suggestive of the UIP pattern in patients in whom surgical lung biopsy was performed.

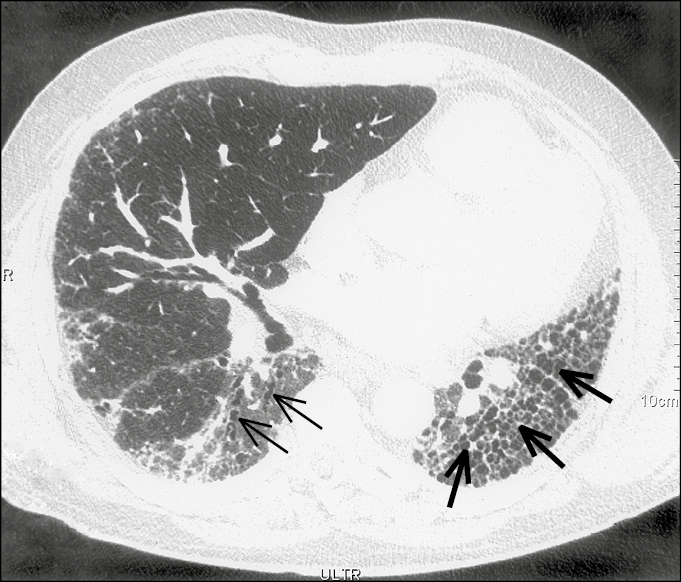

Hence HRCT of the chest is an absolute necessity in the evaluation of ILD. The UIP pattern on HRCT includes basilar-predominant subpleural reticular changes, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing. The presence of honeycombing is favorable when making a diagnosis in the absence of a surgical lung biopsy. It is manifested on HRCT as clustered cystic airspaces, typically of comparable diameters on the order of 3 to 10 mm (Figure 1).

In the absence of a diagnostic gold standard, accuracy is dependent on clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic correlation. This can be best accomplished with expert multidisciplinary discussion, particularly in instances of diagnostic uncertainty.

TreatmentTop

In patients with mild to moderate disease, consider the use of oral pirfenidone 801 mg tid or nintedanib 150 mg bid.Evidence 1Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). A weak rather than a strong recommendation was influenced by the high cost of the drug. Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to sparse data on some patient-important outcomes and indirectness to the most affected subgroups. King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al; ASCEND Study Group. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 29;370(22):2083-92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. Epub 2014 May 18. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 18;371(12):1172. PubMed PMID: 24836312. Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al; INPULSIS Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 29;370(22):2071-82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402584. Epub 2014 May 18. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 20;373(8):782. PubMed PMID: 24836310. Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Pirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: analysis of pooled data from three multinational phase 3 trials. Eur Respir J. 2016 Jan;47(1):243-53. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00026-2015. Epub 2015 Dec 2. PubMed PMID: 26647432; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4697914. Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y, et al; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory society; Japanese Respiratory Society; Latin American Thoracic Association. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Update of the 2011 Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Jul 15;192(2):e3-19. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1063ST. Erratum in: Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Sep 1;192(5):644. Dosage error in article text. PubMed PMID: 26177183. Rochwerg B, Neupane B, Zhang Y, et al. Treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a network meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2016 Feb 3;14:18. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0558-x. PubMed PMID: 26843176; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4741055. Consider antacid therapy in all IPF patients.Evidence 2Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to data based on observational studies. Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y, et al; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory society; Japanese Respiratory Society; Latin American Thoracic Association. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Update of the 2011 Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Jul 15;192(2):e3-19. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1063ST. Erratum in: Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Sep 1;192(5):644. Dosage error in article text. PubMed PMID: 26177183. Immunosuppressive therapy with prednisone and azathioprine should not be used in the long-term management of IPF given an increased risk of hospitalization and death. Do not use anticoagulants in patients with IPF who have no other indications for antithrombotic prophylaxis. Use optimal symptomatic treatment (particularly oxygen therapy in patients with significant hypoxemia at rest) and consider pulmonary rehabilitation in the majority of patients. Consider enrolling patients in clinical studies that evaluate the use of novel therapeutic agents. Referral for lung transplant should be considered in early stages of IPF. Listing for lung transplant should be considered in the case of:

1) A decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) ≥10% during 6 months of follow-up.

2) A decline in diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) ≥15% during 6 months of follow-up.

3) Desaturation to <88%, a distance <250 meters on the 6-minute walk test, or a decline >50 meters in the 6-minute walk distance over a 6-month period.

4) Pulmonary hypertension (on right heart catheterization or echocardiography).

5) Hospitalization because of respiratory decline, pneumothorax, or acute exacerbation.

Acute exacerbations are serious events in IPF with an incidence of 5% to 15% per year and median survival <3 months. Clinical evaluation is required to exclude alternative causes of acute respiratory failure, including pneumonia, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, and other identifiable causes of acute lung injury. Even if there is a lack of evidence for infection, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is usually administered. Glucocorticoids are also often used, based on their potential to treat acute lung injury or organizing pneumonia, and are recommended for the treatment of acute exacerbations despite very limited evidence. Pulse doses of glucocorticoids (IV methylprednisolone 0.5-1 g/d for 3 days) are commonly used, while lower doses (prednisone 1 mg/kg) may be preferred in patients with a milder flare. Both strategies are typically followed by a rapid taper and cessation of prednisone within several weeks. Management strategies involving the use of IV cyclophosphamide should be avoided, as a recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated increased mortality with this approach.Evidence 3Strong recommendation (downsides clearly outweigh benefits; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision. Naccache JM, Jouneau S, Didier M, et al; EXAFIP investigators and the OrphaLung network. Cyclophosphamide added to glucocorticoids in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (EXAFIP): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2022 Jan;10(1):26-34. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00354-4. Epub 2021 Sep 7. PMID: 34506761.

PrognosisTop

The median survival from the time of diagnosis is 3 to 5 years. Significant heterogeneity, however, exists among individual patients, and the clinical course is variable and unpredictable. In some patients the disease is characterized by rapid progression and functional impairment, while others experience a protracted course punctuated by acute exacerbations. The risk of acute exacerbation increases with the severity of lung function impairment. Lung cancer develops in 10% to 15% of patients with IPF.

FiguresTop

Figure 17.8-1. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. A high-resolution computed tomography scan with reticular opacities, traction bronchiectasis (thin arrows), and honeycombing (thick arrows).