Definition, Etiology, Clinical FeaturesTop

Pneumomediastinum is the presence of air in the mediastinum. The most common cause by far is primary spontaneous pneumomediastinum, which results from alveolar rupture due to a sudden increase in alveolar pressure. Secondary pneumomediastinum may occur during mechanical ventilation, surgery, or diagnostic procedures, or it may be a result of chest trauma or severe asthma attack. Less commonly pneumomediastinum may be caused by tracheal, bronchial, or esophageal rupture.

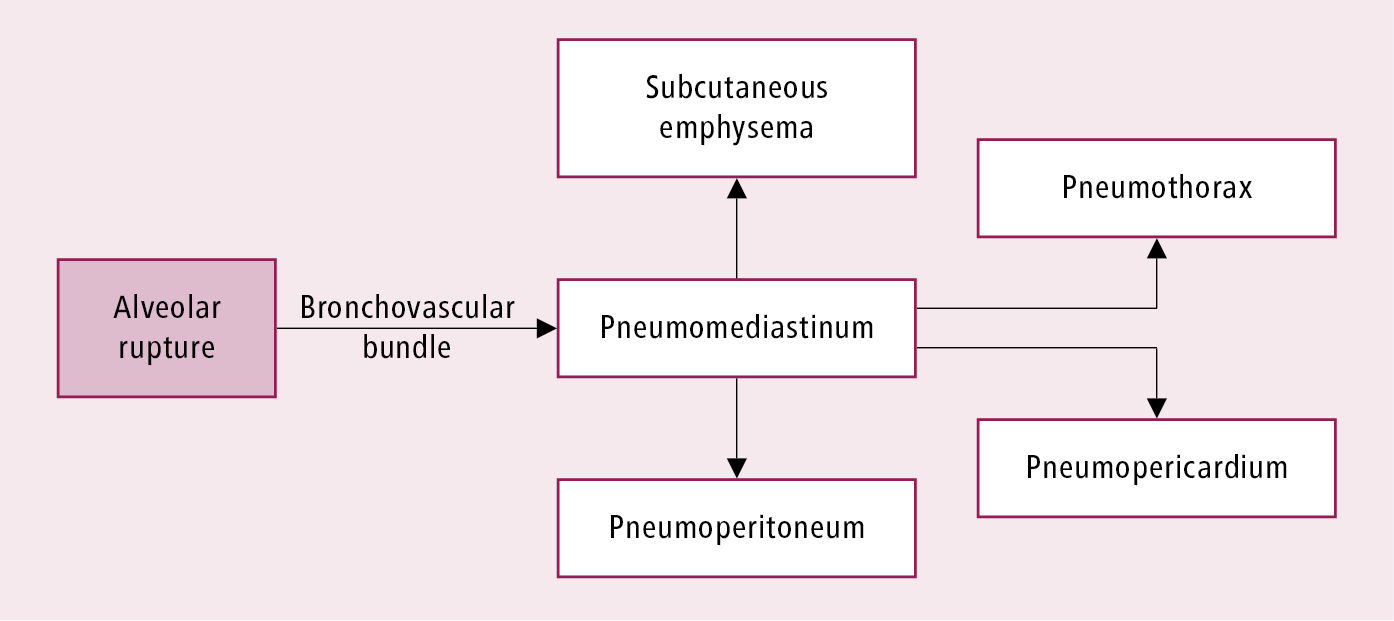

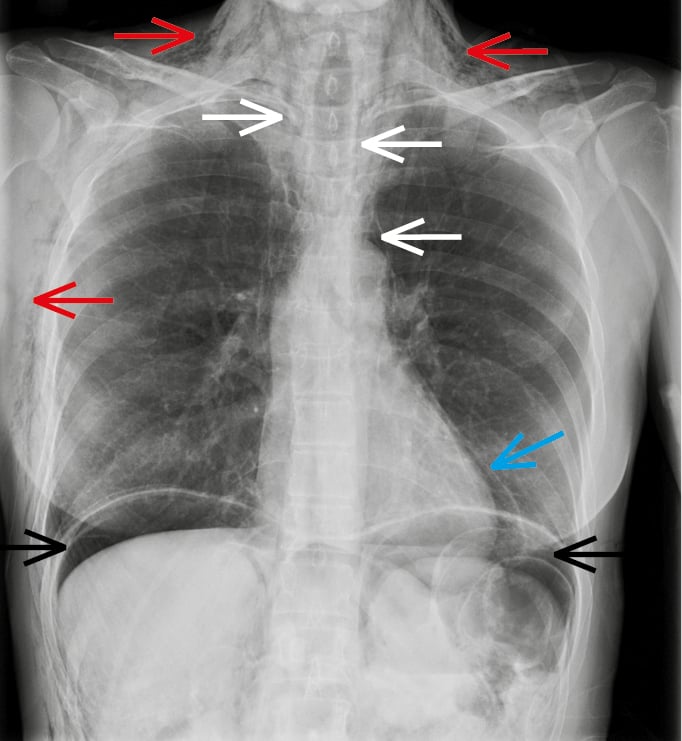

Pathophysiology (Figure 17.10-1, Figure 17.10-2): After alveolar rupture, air penetrates through the peribronchovascular bundle to the mediastinum. Injury to the tracheobronchial wall or esophagus can cause air leak directly into the mediastinum. Continuous air leakage into the mediastinum may result in extension of air spreading into the neck and subcutaneous tissue (subcutaneous emphysema), pericardium (pneumopericardium), pleural space (pneumothorax), or abdominal cavity (pneumoperitoneum). Of note, gas can also originate from gas-forming bacteria infecting the mediastinal soft tissues (mediastinitis).

Symptoms: Chest pain, which worsens with respiration and upon changes of body position; dyspnea; neck discomfort and crackles on compression of the neck and supraclavicular region (if air has entered tissues of the neck); or Hamman sign (audible precordial crunching or creaking sound synchronous with heartbeat, intensifying with inspiration and when lying on the left side).

DiagnosisTop

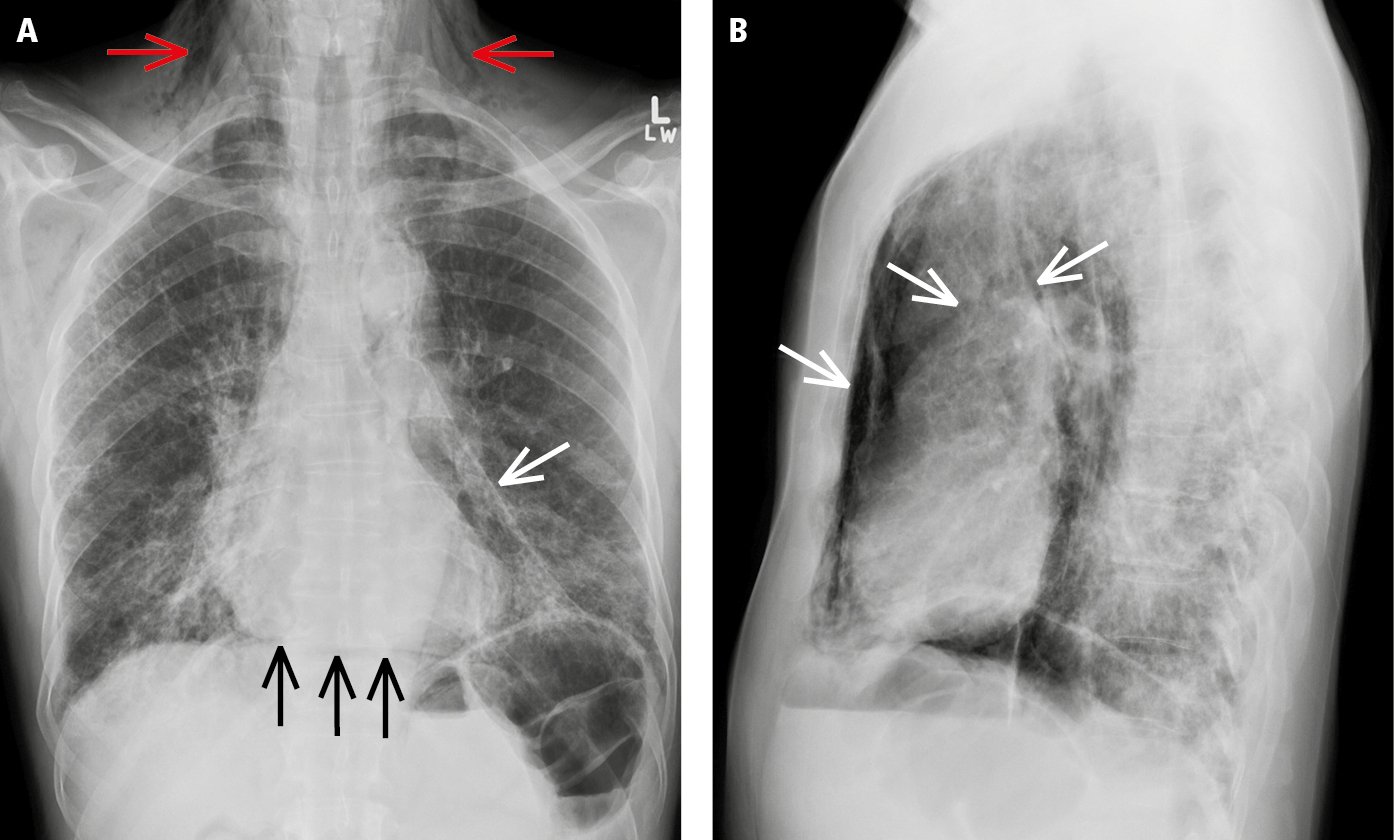

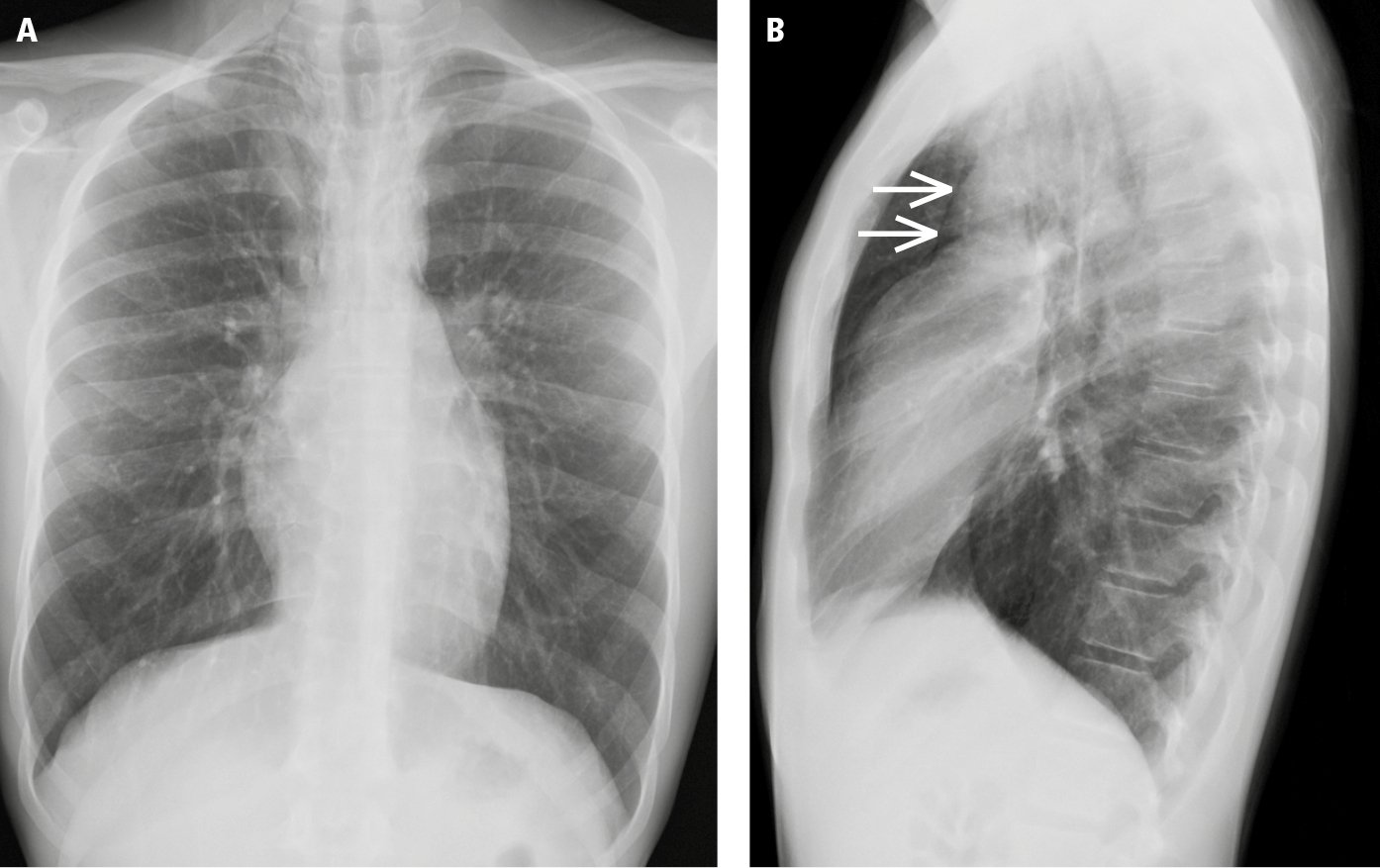

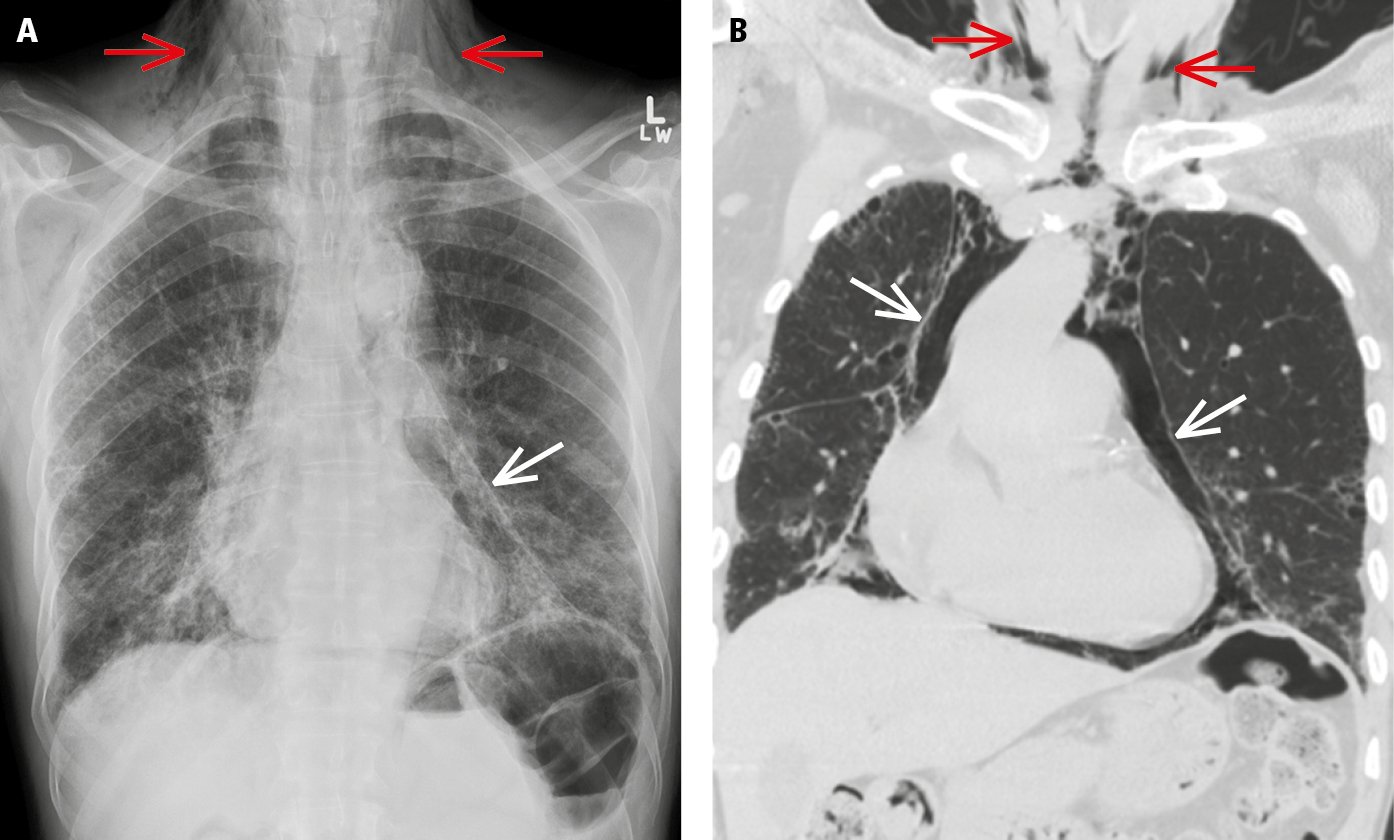

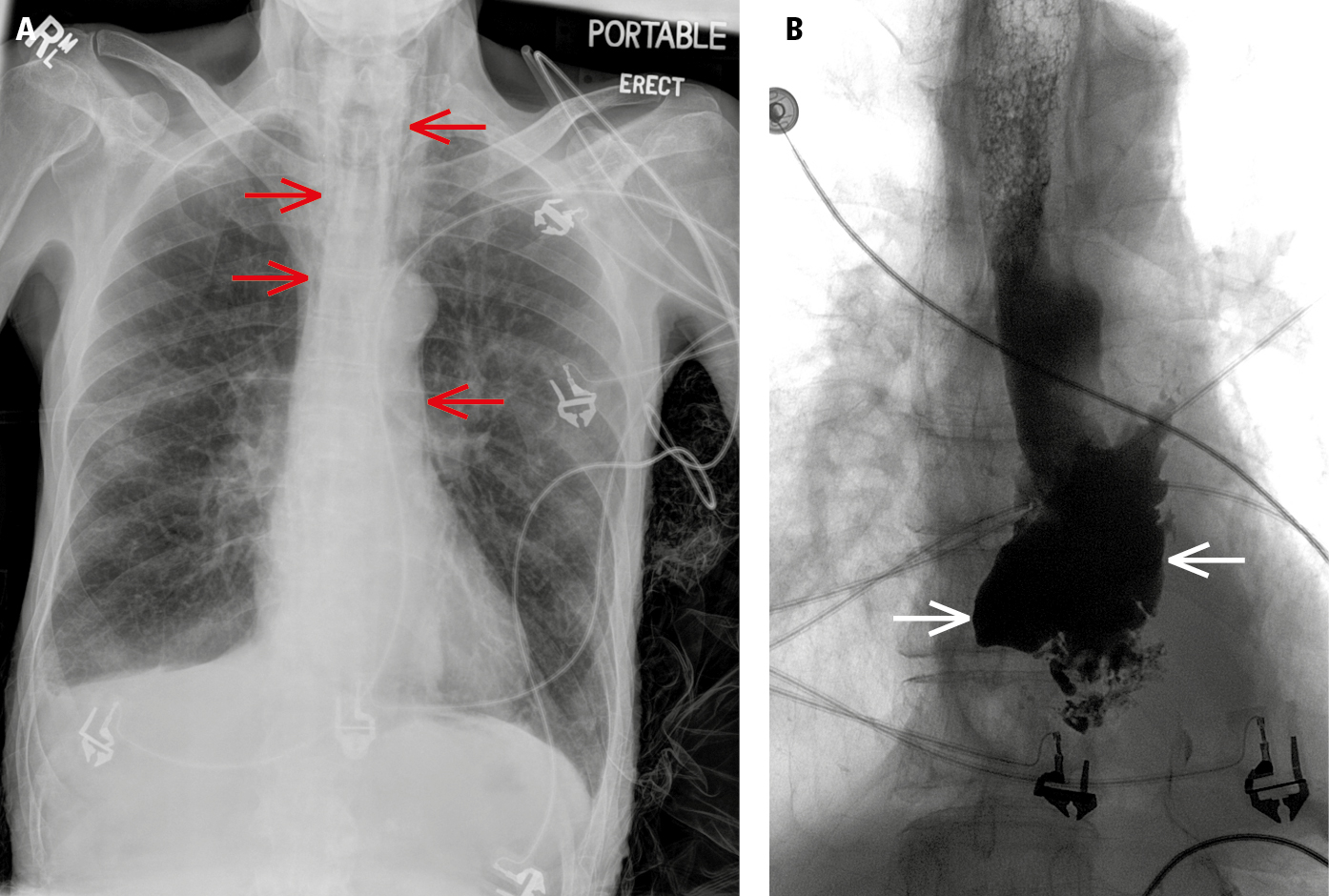

Chest radiographs reveal linear radiolucent areas along the left margin of the cardiac silhouette and sometimes also the “continuous diaphragm” sign (a linear radiolucent area linking the hemidiaphragms under the cardiac silhouette; Figure 17.10-3). Lateral chest radiographs reveal the presence of air behind the sternum and thin radiolucent areas highlighting the contour of the aorta, main pulmonary artery, and other mediastinal structures (Figure 17.10-4). Computed tomography (CT) has greater sensitivity for identifying such abnormalities (Figure 17.10-5). In primary spontaneous pneumomediastinum CT shows evidence of gas locules bilaterally, tracking upwards and downwards into the mediastinum. In secondary pneumomediastinum with tracheal or esophageal perforation, an air-fluid level and rim enhancement are also seen in the mediastinum, indicating infection. If tracheal, bronchial, or esophageal perforation is suspected based on history or imaging, bronchoscopy or esophagoscopy should be performed to evaluate the need for further surgical management (Figure 17.10-6).

ManagementTop

In most patients medical treatment is sufficient, as air from the mediastinum is spontaneously evacuated into the subcutaneous tissue of the neck. In patients undergoing mechanical ventilation, chest tube drainage with suction is frequently required to manage pneumothorax. Lower tidal volumes and lower mean airway pressures should be implemented to prevent progression of pneumomediastinum from volutrauma and barotrauma.

FiguresTop

Figure 17.10-1. Pathophysiology of pneumomediastinum and associated complications.

Figure 17.10-2. Presentation of pneumomediastinum and associated complications. A posteroanterior (PA) chest radiograph of a patient with extensive air leakage demonstrates pneumomediastinum (white arrows), subcutaneous emphysema (red arrows), pneumopericardium (blue arrow), and pneumoperitoneum (black arrows).

Figure 17.10-3. Posteroanterior (PA) chest radiography (A) and left lateral view (B) demonstrate pneumomediastinum (white arrows) and subcutaneous emphysema (red arrows). A linear radiolucent area (black arrows) linking the hemidiaphragms under the cardiac silhouette represents air in the mediastinal soft tissue (the “continuous diaphragm” sign).

Figure 17.10-4. A patient with subtle pneumomediastinum, hardly seen on posteroanterior (PA) chest radiographs (A), that is identified on the basis of a thin radiolucent line highlighting the contour of the aorta (arrows) on the left lateral view (B). This finding represents air in the mediastinal soft tissue.

Figure 17.10-5. Posteroanterior (PA) chest radiograph (A) and computed tomography scan (B) demonstrate pneumomediastinum (white arrows) and subcutaneous emphysema (red arrows).

Figure 17.10-6. Chest radiography (A) shows pneumomediastinum (red arrows) along the paratracheal soft tissues and aorta. Contrast esophagography (B) reveals contrast leakage from the esophagus (white arrows), indicating pneumomediastinum secondary to esophageal rupture.