Pinto-Sanchez MI, Silvester JA, Lebwohl B, et al. Society for the Study of Celiac Disease position statement on gaps and opportunities in coeliac disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec;18(12):875-884. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00511-8. Epub 2021 Sep 15. PMID: 34526700; PMCID: PMC8441249.

Verdu EF, Schuppan D. Co-factors, Microbes, and Immunogenetics in Celiac Disease to Guide Novel Approaches for Diagnosis and Treatment. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1395-1411.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.016. Epub 2021 Aug 17. PMID: 34416277.

Kivelä L, Caminero A, Leffler DA, Pinto-Sanchez MI, Tye-Din JA, Lindfors K. Current and emerging therapies for coeliac disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Mar;18(3):181-195. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00378-1. Epub 2020 Nov 20. PMID: 33219355.

Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó I, et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for Diagnosing Coeliac Disease 2020. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020 Jan;70(1):141-156. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002497. PMID: 31568151.

Pinto-Sanchez MI, Bai JC. Toward New Paradigms in the Follow Up of Adult Patients With Celiac Disease on a Gluten-Free Diet. Front Nutr. 2019 Oct 1;6:153. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00153. PMID: 31632977; PMCID: PMC6781794.

Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. Updated guidelines by the European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019 Jun;7(5):581-582. doi: 10.1177/2050640619849370. Epub 2019 Jun 1. PMID:31210939; PMCID: PMC6545712

Husby S, Murray JA, Katzka DA. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diagnosis and Monitoring of Celiac Disease-Changing Utility of Serology and Histologic Measures: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar;156(4):885-889. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.010. Epub 2018 Dec 19. PMID: 30578783; PMCID:PMC6409202.

Robert ME, Crowe SE, Burgart L, et al. Statement on Best Practices in the Use of Pathology as a Diagnostic Tool for Celiac Disease: A Guide for Clinicians and Pathologists. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018 Sep;42(9):e44-e58. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001107.PMID: 29923907.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for Celiac Disease: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2017 Mar 28;317(12):1252-1257. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1462. PMID: 28350936.

Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC, et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut. 2013 Jan;62(1):43-52. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301346. PubMed PMID: 22345659; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3440559.

Al-Toma A, Volta U, Auricchio R et al. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United European Gastroenterol J 2019; 7(5):583-613.

Bai JC, Fried M, Corazza GR, et al; World Gastroenterology Organization. World Gastroenterology Organization global guidelines on celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017 Feb;51(9):755-68.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Celiac disease (CD) is a chronic immune-mediated enteropathy triggered by gluten in genetically predisposed individuals who carry the HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 haplotype.

Gluten is the collective name for a group of proteins found in wheat (gliadins and glutenins), rye (secalin), and barley (hordein). Gluten proteins have a high concentration of the amino acids proline and glutamine, rendering them resistant to enzymatic degradation by digestive enzymes. As a result, large and potentially immunogenic peptides may reach the mucosa of the small intestine and initiate an immune response. The high proline and glutamine content in gluten peptides also renders them excellent substrates for tissue transglutaminase type 2 (tTG2). tTG2 is a ubiquitous intracellular enzyme that is released extracellularly and activated during inflammation. tTG2 deamidates gluten peptides, which converts glutamine to negatively charged glutamic acid residues, increasing their binding affinity to HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 molecules on antigen-presenting cells. Gluten-specific T cells from patients with CD preferentially recognize deamidated gluten peptides and produce the type 1 helper T cell (Th1) cytokines interferon gamma and interleukin 21 (IL-21). Gluten-specific Th1 cells also provide help for the activation of B cells to form antigluten and anti-tTG2–producing plasma cells.

Contrary to what was previously thought, the onset of CD occurs at any age, and today the disease is more often diagnosed in adulthood. Although ~30% of the world population carries the HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 genes, only 1% will develop the disease. This together with the rising prevalence of CD in the past 40 years suggests that unknown environmental factors may also play a role in disease pathogenesis.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

1. Signs and symptoms: CD is frequently asymptomatic and diagnosis often follows a screening test. However, it may present with different gastrointestinal and extraintestinal manifestations, with extraintestinal symptoms usually predominating in adults:

1) Gastrointestinal: Chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, constipation, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, vomiting, reflux, micronutrient deficiencies, steatohepatitis, and weight loss (rare).

2) Extraintestinal:

a) Cutaneous: Dermatitis herpetiformis (Duhring disease: Figure 7.2-7; ~15%-25% of patients), urticaria, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis (~4%).

b) Hematologic: Iron deficiency anemia (~50% of patients at diagnosis), thrombocytosis, IgA deficiency, leukopenia, neutropenia.Evidence 1Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision and indirectness. Mahadev S, Laszkowska M, Sundström J, Björkholm M, Lebwohl B, Green PHR, Ludvigsson JF. Prevalence of Celiac Disease in Patients With Iron Deficiency Anemia-A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Aug;155(2):374-382.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.016. Epub 2018 Apr 22. PMID: 29689265; PMCID: PMC7057414.

c) Gynecologic: Delayed puberty (including delayed menarche), infertility, recurrent abortions.

d) Neurologic: Central nervous system: seizures, migraine, ataxia; peripheral neuropathy.

e) Psychologic: Anxiety, depression, brain fog.

f) Bones: Osteopenia, osteoporosis, increased risk of bone fractures.

g) Other: Muscle weakness, tetany, short stature, dental enamel defects.

2. Clinical classification of CD: Table 7.2-5.

3. Natural history: Undiagnosed or untreated CD may lead to complications, some of them serious (eg, increased risk of bone fractures and certain types of cancers). The clinical course of CD depends on strict adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD). Poor adherence is associated with increased risk of complications and mortality. The most common complications associated with CD:

1) Gastrointestinal: Pharyngeal or esophageal cancer, lymphoma or cancer of the small intestine, refractory CD (symptoms persisting despite adherence to a GFD).

2) Hematopoietic: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

3) Urogenital: Infertility, recurrent miscarriage, premature birth, premature menopause.

4) Musculoskeletal: Osteoporosis and increased risk of bone fractures.

DiagnosisTop

CD may be suspected in:

1) Symptomatic patients with:

a) Gastrointestinal symptoms and signs: Diarrhea, weight loss, gas/bloating, constipation (more commonly in children), elevated aminotransferase levels.

b) Extraintestinal symptoms and signs: Iron deficiency anemia, dermatitis herpetiformis, osteoporosis, neuropsychiatric conditions (eg, neuropathy, ataxia).

2) Patients with associated conditions: Autoimmune thyroiditis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, Down syndrome, other autoimmune conditions.

3) First-degree family members of patients with CD.

Diagnostic tests should be performed in patients consuming a gluten-containing diet (≥6 weeks of daily intake of ≥1 meal containing gluten).

1. General laboratory tests:

1) Hemoglobin to investigate for anemia (a frequent abnormality in adults); most likely iron deficiency anemia, rarely megaloblastic anemia.

2) Micronutrients: Reduced serum levels of iron, folic acid, calcium, vitamins D, B6, B12, zinc, copper, selenium.

3) Hypoalbuminemia (due to protein loss into the gastrointestinal tract).

4) Liver enzymes (transient elevation of liver aminotransferases is seen in active CD).

2. Specific serology: IgA antibodies to tTG (total IgA levels must also be measured to exclude IgA deficiency), EmA IgA, and DGPs are used for the diagnosis of CD. tTG IgA antibody is the preferred single test for detection of CD in individuals aged >2 years.Evidence 2Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, Calderwood AH, Murray JA; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108(5):656-76; quiz 677. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.79. Epub 2013 Apr 23. PubMed PMID: 23609613; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3706994. Sheppard AL, Elwenspoek MMC, Scott LJ, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the accuracy of serological tests to support the diagnosis of coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022 Mar;55(5):514-527. doi: 10.1111/apt.16729. Epub 2022 Jan 18. PMID: 35043426. Because of their low sensitivity and specificity, the use of antigliadin antibodies (IgA and IgG) for the diagnosis of CD is discouraged. In patients with IgA deficiency IgG antibodies to tTG2 or DGPs are useful tools for CD diagnosis. DGP IgG can be added as a second test to increase the sensitivity of tTG IgA; however, the use of DGP IgG in individuals with sufficient IgA has been controversial, as it may lead to false-positive results.

EmA IgA is the most specific test for the diagnosis of CD, but it requires immunofluorescence and is operator-dependent. EmA IgG has lower sensitivity compared with EmA IgA.

Indications for serologic studies:

1) Case finding in patients with suspected CD.

2) Screening in high-risk groups (eg, family members of patients with diagnosed CD; patients with related autoimmune diseases, such as type 1 diabetes mellitus or hypothyroidism).

3) Monitoring of adherence to a GFD. In patients with good adherence the results of serologic tests normalize in the first year after diagnosis.

3. Endoscopy: Grooved or scalloped margins of duodenal folds, reduction in the number of folds (which are flattened or atrophic), a mosaic pattern of the mucosal surface, and prominent submucosal blood vessels (normally not visible).

4. Histologic examination of duodenal biopsies is key for the diagnosis of CD, particularly in adult patients. The tissue samples (≥4 biopsy specimens collected from the second and third portion of duodenum and 1-2 biopsy specimens from the duodenal bulb) are usually obtained by esophagogastroduodenoscopy. A typical histologic finding is villous atrophy accompanied by high intraepithelial lymphocyte count (ILC) and hyperplasia of intestinal crypts (villous atrophy). Marsh classification: 0 means normal biopsy result; 1, increased ILC; 2, increasing degree of crypt hyperplasia; 3, villous atrophy (3a = mild; 3b = moderate, 3c = severe).

5. Genetic testing: The great majority (95%-99%) of patients with CD carry the HLA-DQ2 haplotype and the remaining patients (5%-10%) carry HLA-DQ8. In rare cases (<1%) patients not carrying these heterodimers express the other half of the DQ2.5 heterodimer (DQ7.5). Therefore, the absence of HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 molecules practically excludes the diagnosis of CD. However, ~30% of the general population carries HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 in the absence of CD; therefore, HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 should not be used for the diagnosis of CD.Evidence 3Strong recommendation (downsides clearly outweigh benefits; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Al-Toma A, Volta U, Auricchio R, et al. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019 Jun;7(5):583-613. doi: 10.1177/2050640619844125. Epub 2019 Apr 13. Review. PubMed PMID: 31210940; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6545713. HLA-DQ2/DQ8 testing is indicated to exclude CD in the following situations:

1) Marsh type 1 or 2 histology in patients with negative CD serology.

2) Assessment of the risk for CD in patients on a GFD not previously investigated for CD.

3) Discrepancy between CD-specific serology and histology results.Evidence 4Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. Al-Toma A, Volta U, Auricchio R, et al. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019 Jun;7(5):583-613. doi: 10.1177/2050640619844125. Epub 2019 Apr 13. Review. PubMed PMID: 31210940; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6545713.

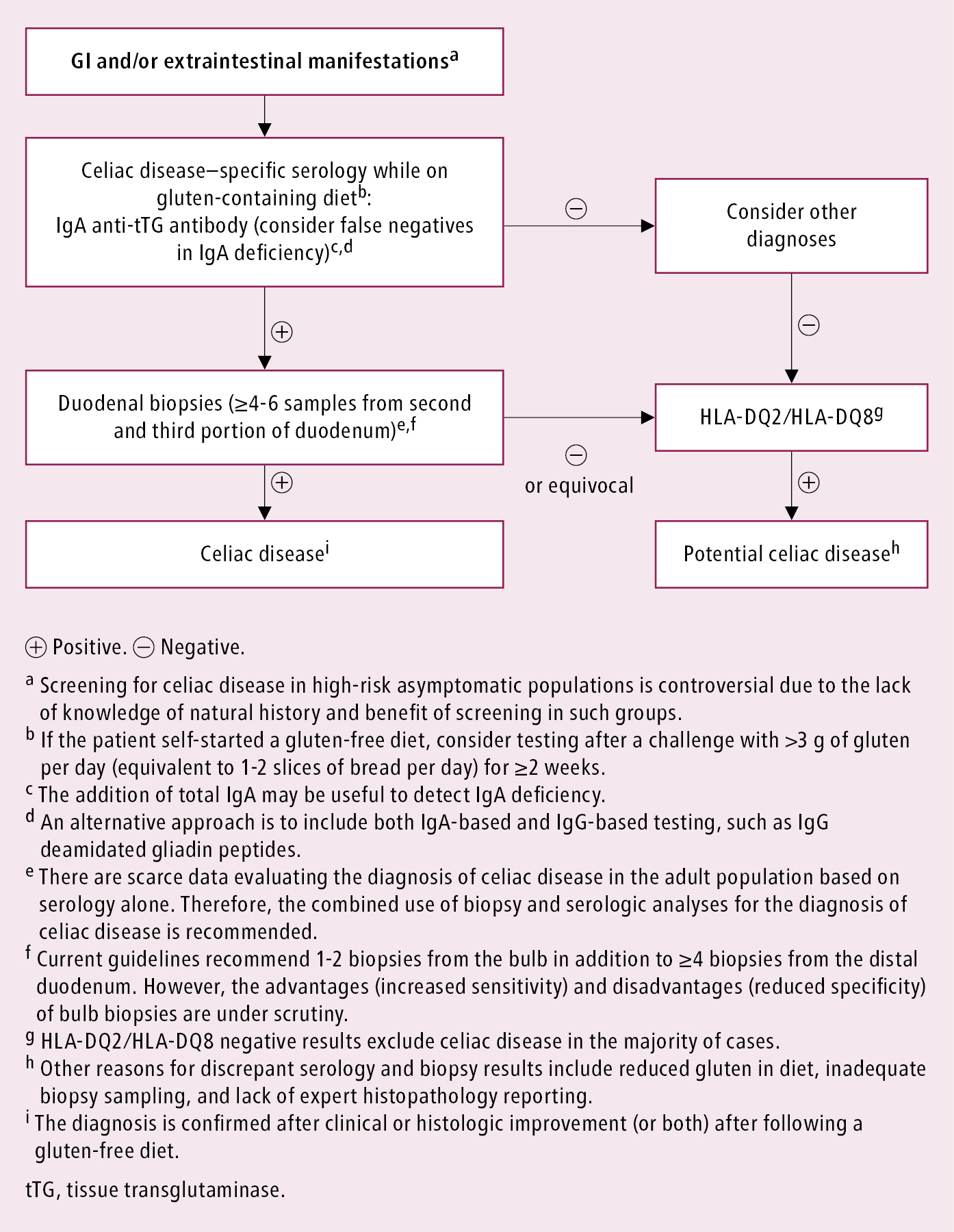

Positive serologic study results and typical histologic findings. General diagnostic algorithm: Figure 7.2-8.

Differential diagnosis should include other causes of enteropathy (villous atrophy): chronic giardiasis, tropical sprue, protein malnutrition, anorexia nervosa, food hypersensitivity (lesions are usually focal), viral infection (including HIV), bacterial infection (eg, tuberculosis), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), Whipple disease, postradiation complications, drug-induced enteropathy (eg, by olmesartan), immunodeficiency (eg, hypogammaglobulinemia, common variable immunodeficiency), Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, and lymphoma of the small intestine.

TreatmentTop

The only currently available treatment for CD is adherence to a strict GFD. Very small amounts of gluten (50 mg or a breadcrumb) can induce inflammatory changes in the small intestine and triggering symptoms in patients with CD.

1. GFD: Lifelong elimination of all wheat, rye, and barley products.

Products allowed: Dairy products (liquid and powdered milk, hard cheese, cottage cheese, cream, eggs); all meats and meat products (note: diced bread and semolina may be added to certain meat products such as sausages, pates, liverwurst), offal (liver, lungs, kidneys), fish; all fruits and vegetables; nuts; rice, corn, soybeans, tapioca, buckwheat; all fats; sugar, honey; spices, salt, and pepper; coffee, tea, cocoa; gluten-free breads, cakes, and desserts. Gluten-free products are often labeled with a crossed-grain symbol.

Products not allowed: Wheat, rye, barley, and noncertified gluten-free oat products (as they are often contaminated with gluten); bread rolls, white bread, whole-grain bread, crispbread; pasta; semolina, barley; other products containing gluten, such as cakes, biscuits, confectionery.

Supplementation of iron, folic acid, calcium, zinc, vitamin D, and sometimes vitamin B12 may be indicated (in case of deficiency).

2. Immunosuppressive drugs (eg, glucocorticoids, azathioprine, cyclosporine [INN ciclosporin]) may be prescribed in refractory CD not responding to dietary restrictions.

3. Treatment difficulties and future pharmacologic therapies: A strict GFD is difficult to achieve and follow in the long term. Without proper monitoring, following a GFD can lead to nutritional deficiencies. The diet is also expensive. Therefore, nonadherence, either voluntary or through inadvertent contamination, is common. This highlights the need for development of adjuvant therapies to the GFD. Multiple investigational therapies ranging from tolerogenic to immunologic approaches are under investigation, and the most advanced candidates including tight junction modulator (larazotide acetate), specific endopeptidases (gluten-degrading enzymes), monoclonal antibodies (anti-IL-15 monoclonal antibody PRV-015), and tTG2 inhibitors (ZED-1227) are in phase 2/3 clinical trials. These potential new therapies are to be used as adjuvants of GFD and are intended to protect the patient from inadvertent gluten cross-contamination. In addition, curative therapies based on potential induction of tolerance to gluten are being developed. A phase 2 clinical trial (Nexvax2) was discontinued in June 2019, when early results showed no protection from gluten exposure when compared with placebo. A vaccine candidate (TIMP-GLIA), using nanoparticles containing fragments of the gluten protein, gliadin, is currently under development. Phase 1 studies have been completed and a phase 2 study is planned to start in 2022.

4. Monitoring of treatment effectiveness is based on expert recommendations and includes:

1) Evaluation of adherence to the GFD and nutritional status of the patient by a dietitian; testing for gluten immunogenic peptides (GIPs) in stool or urine.

2) Monitoring CD activity through specific serologic studies (tTG2 and/or DGP) performed every 4 to 6 months until reaching undetectable levels. Undetectable levels of tTG2 and DGP are an indirect confirmation of adherence to a GFD.

3) Monitoring complications associated with CD such as nutrient deficiencies or reduced bone mineral density, which may increase the risk of bone fractures.

5. Nonresponsive CD: Patients with symptoms and sings of malabsorption (abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss) and histologic or serologic abnormalities that persist or recur despite adopting a GFD for ≥6-12 months are considered nonresponsive CD (in European guidelines labeled as nonresponders). The most common reason for nonresponsive CD is inadvertent gluten exposure. Therefore, the first approach is an exhaustive assessment of adherence to the GFD. Once gluten exposure has been excluded, symptoms may be attributed to other common associated conditions, including exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, inflammatory bowel diseases, microscopic colitis, or functional disorders including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Patients with CD may develop an eating disorder leading to persistent symptoms in the follow-up.

A very small proportion of patients with nonresponsive CD may develop refractory celiac disease (RCD) (1% of patients with CD or 10% of patients with nonresponsive CD). RCD patients are recognized for persistent symptoms and signs of malabsorption and villous atrophy despite 1 year of following a strict GFD. tTG2 or CD serology is often negative, supporting the strict adherence to a GFD. There are 2 types of RCD, based on the evidence of aberrant patterns of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs). RCD type 1 has a typical pattern of IELs (CD3+ and CD8+) and is associated with better prognosis compared with RCD type 2 (aberrant pattern of IELs: CD3− and CD8−), which is associated with mortality and risk of lymphoma of 50% at 5 years. Management of RCD patients is complex and they are usually followed up in specialized centers.

Follow-UpTop

Regular follow-up is recommended after the diagnosis of CD is made.

1. In the first year follow-up visits need to be more frequent to improve dietary adherence, provide psychological support, and optimally motivate the patient to adapt to changes. Even though the evidence on the frequency of visits and type of tests that should be performed is low, guidelines recommend follow-up visits with the physician and ideally a dietitian at 4 to 6 months and 12 months in the first year. The objectives are to symptom assessment, dietary review, CD serologic testing (tTG2 or DGPs). Nutrients should be monitored at this stage only if they were low at diagnosis. Follow-up endoscopy is not necessary in asymptomatic patients, as mucosal healing is seen only in 30% of individuals in the first year of a strict GFD.

2. After one year or when results of serologic testing become negative, annual visits are recommended to monitor GFD adherence, CD serology (tTG2 or DGPs), and nutrients (iron, copper, zinc, selenium, folate, vitamin B12). Bone density measurements may be repeated at 1 to 2 years if the results were abnormal at diagnosis. If osteopenia or osteoporosis are present, in addition to a strict GFD it is prudent to ensure adequate calcium and vitamin D intake for all patients. Follow-up endoscopy is reasonable after 2 years of starting a GFD to assess for mucosal healing, especially in patients with severe initial presentation or persistent symptoms in the follow-up.

3. It is advisable to screen first-degree family members for CD.

4. Assessment by a skilled dietitian is the gold standard for evaluating GFD adherence, but it is time-consuming (each visit takes 45 minutes to 1 hour). New tools for detecting GIPs in stool or urine by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (currently available in research settings) or as point-of-care testing (commercially available online) may be useful to identify inadvertent gluten consumption. The tests are highly sensitive (98%) and specific (100%) for detecting gluten consumption within 4 to 5 days (stool) or 1 to 2 days (urine). Gluten can be detected in food by a similar method, using a point-of-care sensor (commercially available online).

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Descriptors of CD |

Characteristics |

|

Classical CD |

Symptoms and signs of malabsorption including diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss; in children growth failure is required |

|

Nonclassical CD |

CD presenting with extraintestinal symptoms but without symptoms of malabsorption |

|

Symptomatic CD |

Clinically evident GI and/or extraintestinal symptoms attributable to gluten intake |

|

Asymptomatic CD |

Lack of GI or extraintestinal symptoms at diagnosis |

|

CD autoimmunity |

Increased antibodies to tTG2 or EMAs on ≥2 occasions (if biopsy is negative, it is “potential CD”; if positive, it is CD) |

|

Subclinical CD |

CD below threshold for clinical detection without symptoms or signs sufficient to trigger CD-testing in routine practice |

|

Potential CD |

Positive CD serology with normal small intestinal mucosa |

|

Genetically at risk for CD |

Family members of patients with CD who test positive for HLA-DQ2 and/or HLA-DQ8 |

|

Refractory CD |

Persistent villous atrophy and malabsorptive symptoms and signs of active CD despite strict gluten-free diet for >12 months |

|

CD, celiac disease; EMA, endomysial antibody; GI, gastrointestinal; tTG2, tissue transglutaminase type 2. | |

Figure 7.2-7. Dermatitis herpetiformis (Duhring disease).

Figure 7.2-8. Approach to the diagnosis of celiac disease in the adult population. Adapted with permission from the Society for the Study of Celiac Disease.