Hawkins AT, Davis BR, Bhama AR, et al; Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 2024 May 1;67(5):614-623. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000003276. Epub 2024 Jan 31. PMID: 38294832.

Davids JS, Hawkins AT, Bhama AR, et al; Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Anal Fissures. Dis Colon Rectum. 2023 Feb 1;66(2):190-199. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002664. Epub 2022 Nov 1. PMID: 36321851.

Gaertner WB, Burgess PL, Davids JS, et al; Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Anorectal Abscess, Fistula-in-Ano, and Rectovaginal Fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022 Aug 1;65(8):964-985. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002473. Epub 2022 Jul 5. PMID: 35732009.

Steele SR, Hull TL, Hyman N, Maykel JA, Read TE, Whitlow CB, eds. The ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery. 4th ed. New York: Springer; 2022.

Wald A, Bharucha AE, Limketkai B, et al. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Management of Benign Anorectal Disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Oct 1;116(10):1987-2008. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001507. PMID: 34618700.

Mocanu V, Dang JT, Ladak F, et al. Antibiotic use in prevention of anal fistulas following incision and drainage of anorectal abscesses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2019 May;217(5):910-917. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.01.015. Epub 2019 Jan 31. PMID: 30773213.

Seow-En I, Ngu J. Routine operative swab cultures and post-operative antibiotic use for uncomplicated perianal abscesses are unnecessary. ANZ J Surg. 2017 May;87(5):356-359. doi: 10.1111/ans.12936. Epub 2014 Nov 21. PubMed PMID: 25413131.

Perera N, Liolitsa D, Iype S, et al. Phlebotonics for haemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Aug 15;(8):CD004322. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004322.pub3. PMID: 22895941.

Nelson RL, Thomas K, Morgan J, Jones A. Non surgical therapy for anal fissure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Feb 15;2012(2):CD003431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003431.pub3. PMID: 22336789; PMCID: PMC7173741.

Sözener U, Gedik E, Kessaf Aslar A, et al. Does adjuvant antibiotic treatment after drainage of anorectal abscess prevent development of anal fistulas? A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011 Aug;54(8):923-9. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31821cc1f9. PubMed PMID: 21730779.

Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, Rao S. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006 Apr;130(5):1510-8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.064. PMID: 16678564.

Clinical Practice Committee, American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: Diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhoids. Gastroenterology. 2004 May;126(5):1461-2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.001. PMID: 15131806.

Definition, Etiology, ClassificationTop

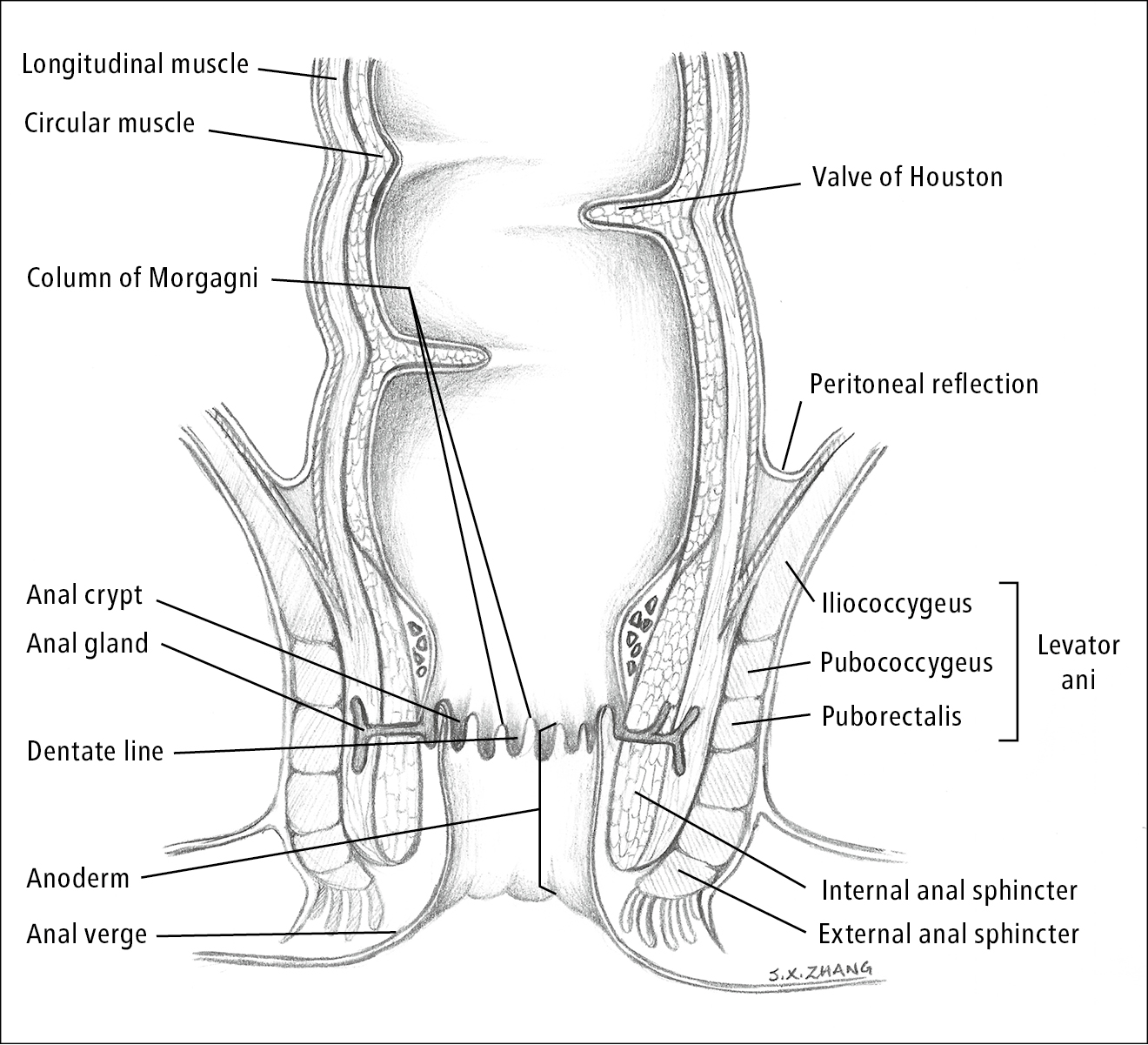

Anal canal anatomy and anorectal spaces: Figure 7.2-3.

Anorectal abscess and fistula in ano are entities along a spectrum of disease with the same underlying pathophysiology.

Anorectal abscesses are infections that usually develop as a result of obstruction of anal crypts with subsequent stasis in anal ducts and glands (also described as of cryptoglandular origin). Less common causes are inflammatory bowel disease, trauma, and malignancy. Anorectal abscesses occur most frequently in patients aged 20 to 40 years and are more frequent in men than in women.

A fistula is defined as an abnormal connection between two epithelialized surfaces. A fistula in ano is an abnormal communication between the anal canal (usually at the level of the dentate line) and the skin. It develops due to chronic infection and epithelialization of a tract that has developed between an abscess and the skin. Fistula in ano occurs in 30% to 70% of patients presenting with an anorectal abscess. About 20% to 40% of patients that do not have a concomitant fistula will develop a fistula after drainage of the abscess.

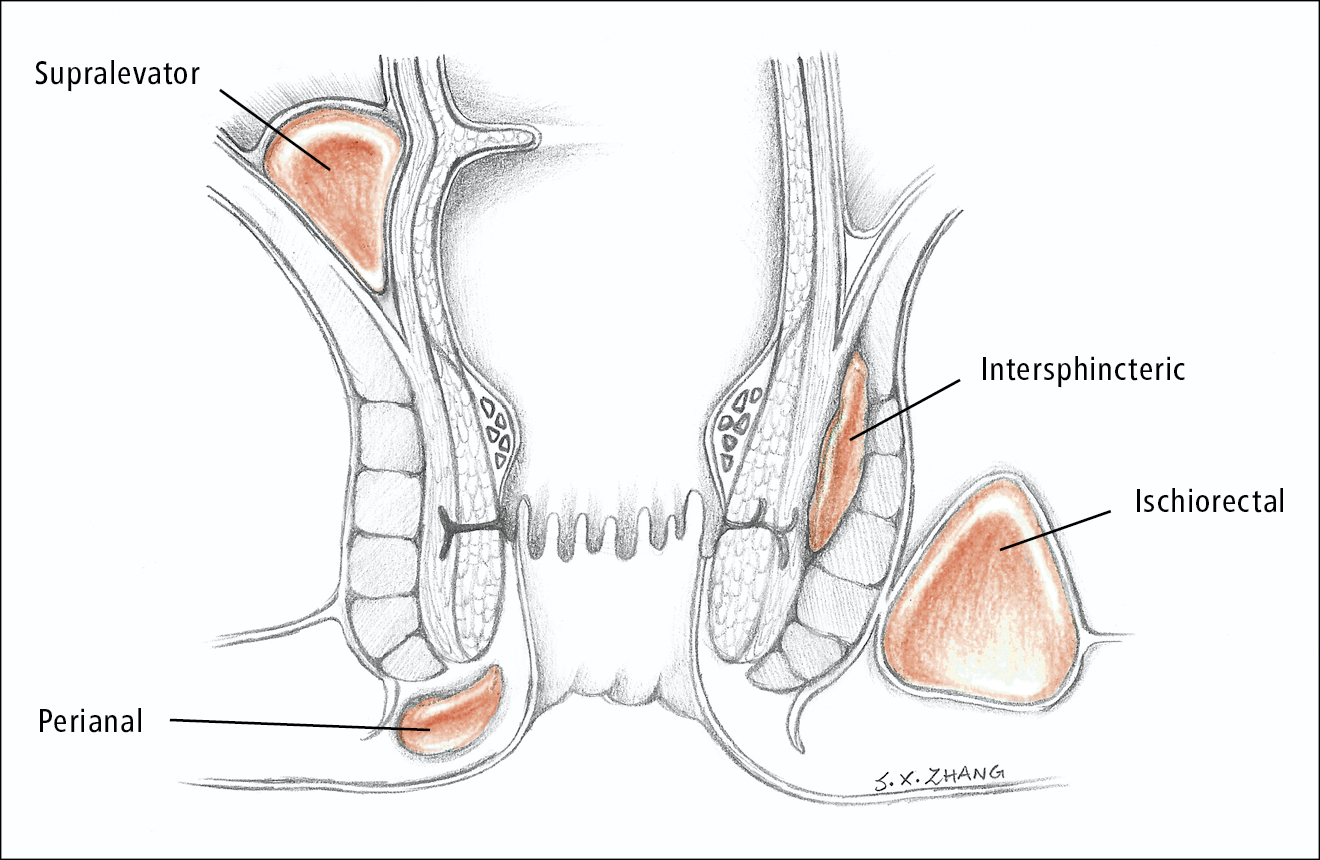

Abscesses are classified based on the anatomic location in which they develop. They can be classified as perianal, ischiorectal, intersphincteric, or supralevator (Figure 7.2-4). Horseshoe abscesses are those that track to the contralateral side via the deep postanal space. Perianal and ischiorectal abscesses compose about 80% of anorectal abscesses.

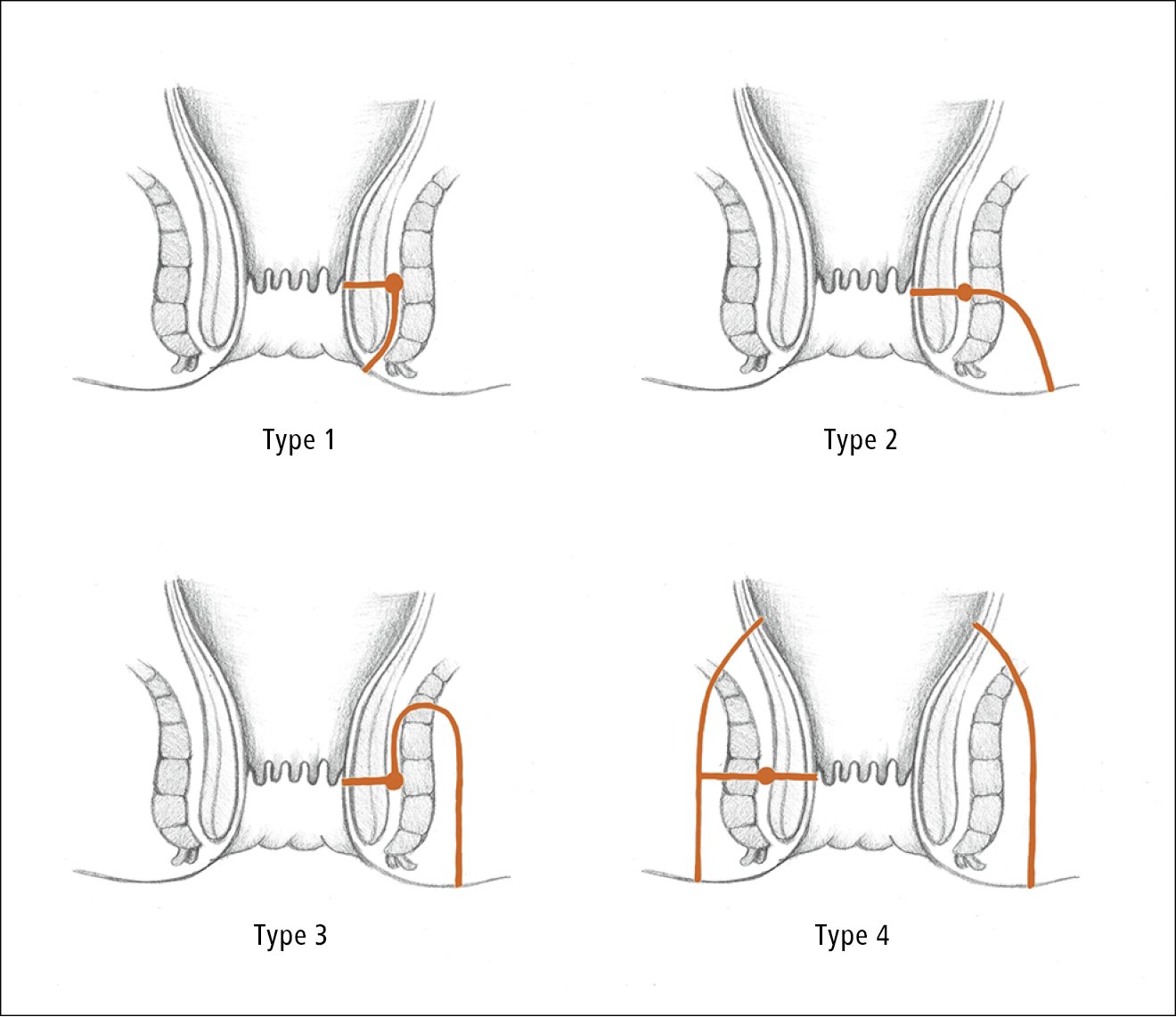

Fistulas may be classified based on their relationship to the external anal sphincter (Figure 7.2-5). Intersphincteric fistulas penetrate only through the internal anal sphincter. Transsphincteric fistulas penetrate through both internal and external sphincters. Suprasphincteric fistula tracts loop over the external sphincter and perforate the levator ani. Extrasphincteric fistulas are completely external to the sphincter complex. Intersphincteric and transsphincteric fistulas are most common.

Fistulas can also be classified as simple versus complex fistulas. Simple fistulas are intersphincteric or transsphincteric fistulas that do not involve a significant portion of the external sphincter (<30%). The following are classified as complex fistulas: transsphincteric fistulas involving a significant amount of the external sphincter; anterior fistulas in women; suprasphincteric fistulas; extrasphincteric fistulas; horseshoe fistulas; and fistulas associated with inflammatory bowel disease, radiation, or malignancy.

Clinical FeaturesTop

The most common symptoms of anorectal abscesses are acute perianal pain and swelling. Patients may report spontaneous drainage. Less commonly fever and malaise develop. Supralevator abscesses may present with referred pain in the lower back and buttocks.

The clinical complaints most suggestive of a fistula are intermittent perianal pain and swelling with constant or occasional drainage of purulence, blood, or stool from the external opening of the fistula. Exacerbation of the inflammatory process, with subsequently worsened pain and swelling, often follows a spontaneous closure of the external opening (ie, increased pain and swelling after drainage stops).

It is important to elicit information about sphincter function, prior anorectal surgery, and any associated gastrointestinal, urologic, or gynecologic history (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, anal carcinoma, vaginal delivery, pelvic radiation).

Physical examination starts with inspection of the perineum. Erythema, swelling, spontaneous drainage, external openings of fistula in ano, or other signs of perianal Crohn disease are noted. External perianal and digital rectal examinations (DRE) are done to identify areas of induration, fluctuance, and tenderness. An intersphincteric abscess should be suspected if there is exquisite tenderness and fluctuance on DRE with a relatively unremarkable external examination. Careful examination of the contralateral perianal side should also be performed to exclude a horseshoe abscess. Physical examination is not very helpful in supralevator abscesses.

DiagnosisTop

Clinical examination is usually sufficient for diagnosis. However, if there is uncertainty or physical examination cannot be performed due to pain, the patient may require imaging or examination under anesthesia with anoscopy.

Imaging studies may be helpful in occult or complicated anorectal abscesses and Crohn disease, although they are not typically necessary. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may identify and characterize abscesses and fistulas. MRI is more helpful in identifying and delineating fistulas.

TreatmentTop

1. Abscess: Prompt incision and complete drainage of the abscess is required. Incision should be large enough for adequate drainage and as close as possible to the anal verge without damaging the sphincter complex to minimize the length of the potential fistula.

Previously, antibiotic therapy following incision and drainage was only considered for patients with significant cellulitis, systemic signs, or underlying immunosuppression. However, more recent evidence suggests that a short course of oral antibiotics may reduce the risk of subsequent fistula formation.Evidence 1Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to significant indirectness and heterogeneity (variability in administration dose, site, and frequency of injections in the studies as well as variability in healing rates reported in the studies). Mocanu V, Dang JT, Ladak F, et al. Antibiotic use in prevention of anal fistulas following incision and drainage of anorectal abscesses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2019 May;217(5):910-917. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.01.015. Epub 2019 Jan 31. PMID: 30773213. Seow-En I, Ngu J. Routine operative swab cultures and post-operative antibiotic use for uncomplicated perianal abscesses are unnecessary. ANZ J Surg. 2017 May;87(5):356-359. doi: 10.1111/ans.12936. Epub 2014 Nov 21. PMID: 25413131. Sözener U, Gedik E, Kessaf Aslar A, et al. Does adjuvant antibiotic treatment after drainage of anorectal abscess prevent development of anal fistulas? A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011 Aug;54(8):923-9. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31821cc1f9. PMID: 21730779.

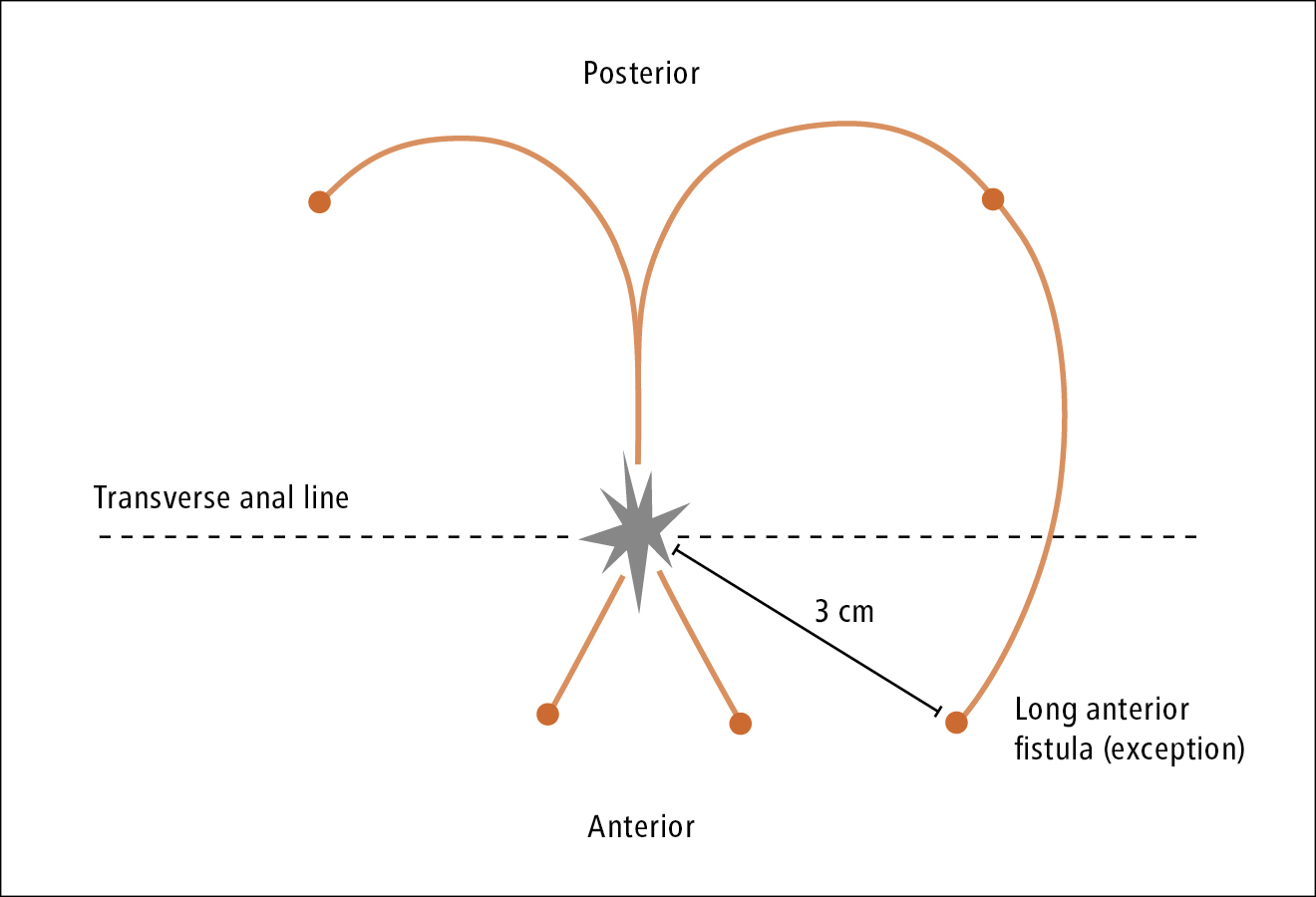

2. Fistula: The first step in treatment is an examination under anesthesia, which is performed to confirm diagnosis, identify the internal opening(s), and define the anatomy of the fistula tract(s). Goodsall rule is helpful in locating the internal opening of the fistula (Figure 7.2-6). To apply the rule, an imaginary line is drawn transversely across the buttocks, through the anus. If the external opening of a fistula is anterior to this line, the tract will likely be a straight radial tract with the internal opening at the end of this straight tract along the anterior midline. If the external opening is posterior to this line, the tract will likely be curved, with the internal opening along the posterior midline location. An exception is an external opening anterior to this line but further away from the anus (>3 cm), which suggests that the fistula tract may actually be curvilinear and originating along the posterior midline.

Surgical treatment may require multiple stages, depending on the characteristics of the fistula. Surgical treatment for a simple fistula with normal sphincter function is a fistulotomy.Evidence 2Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the observational nature of the studies that demonstrate high success rates of fistulotomy (>90% healing rate, high patient satisfaction) and imprecision of the randomized controlled trials comparing surgical options. Abramowitz L, Soudan D, Souffran M, et al; Groupe de Recherche en Proctologie de la Société Nationale Française de Colo-Proctologie and the Club de Réflexion des Cabinets et Groupe d'Hépato-Gastroentérologie. The outcome of fistulotomy for anal fistula at 1 year: a prospective multicentre French study. Colorectal Dis. 2016 Mar;18(3):279-85. doi: 10.1111/codi.13121. PubMed PMID: 26382623. Jacob TJ, Perakath B, Keighley MR. Surgical intervention for anorectal fistula. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 May 12;(5):CD006319. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006319.pub2. Review. PMID: 20464741. Hall JF, Bordeianou L, Hyman N, et al. Outcomes after operations for anal fistula: results of a prospective, multicenter, regional study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014 Nov;57(11):1304-8. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000216. PMID: 25285698. In patients with complex fistulas, when continence and/or wound healing may be compromised with surgical treatment, it is necessary to place a seton (drain) to ensure drainage of perianal sepsis and mature the fistula tract to allow for subsequent definitive management. Definitive surgical treatments may include ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) and endoanal advancement flaps; the effectiveness of LIFTs has been questioned in recent years. Fistula plugs and fibrin glue are relatively ineffective. Complex fistulas in the setting of Crohn disease are often best managed with seton placement (surgical thread or string placed through a fistula) and optimization of medical/biologic therapy.

FiguresTop

Figure 7.2-3. Anal canal anatomy. Illustration courtesy of Dr Shannon Zhang.

Figure 7.2-4. Location of abscesses. Illustration courtesy of Dr Shannon Zhang.

Figure 7.2-5. Types of fistula in ano. Type 1, intersphincteric fistula. Type 2, transsphincteric fistula. Type 3, suprasphincteric fistula. Type 4, extrasphincteric fistula. Illustration courtesy of Dr Shannon Zhang.

Figure 7.2-6. Goodsall rule. Illustration courtesy of Dr Shannon Zhang.