Douglas RS, Kahaly GJ, Patel A, et al. Teprotumumab for the Treatment of Active Thyroid Eye Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan 23;382(4):341-352. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910434. PMID: 31971679. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31971679/

Ross DS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al. 2016 American Thyroid Association Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Hyperthyroidism and Other Causes of Thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid. 2016 Oct;26(10):1343-1421. Erratum in: Thyroid. 2017 Nov;27(11):1462. PubMed PMID: 27521067.

Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Disease During Pregnancy and the Postpartum. Thyroid. 2017 Mar;27(3):315-389. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0457. Erratum in: Thyroid. 2017 Sep;27(9):1212. PubMed PMID: 28056690.

Bartalena L, Baldeschi L, Boboridis K, et al; European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy (EUGOGO). The 2016 European Thyroid Association/European Group on Graves' Orbitopathy Guidelines for the Management of Graves’ Orbitopathy. Eur Thyroid J. 2016 Mar;5(1):9-26. doi: 10.1159/000443828. Epub 2016 Mar 2. PMID: 27099835; PMCID: PMC4836120.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Graves disease (GD) is an autoimmune disease in which the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor (TSH-R) is the autoantigen. Stimulation of this receptor in the thyroid gland by TSH-R antibodies (TRAb) results in increased secretion of thyroid hormones, development of signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism, thyroid hypertrophy, and vascular proliferation. The activation of cellular immune-response mechanisms against the same antigen present in orbital and skin fibroblasts results in the development of clinical symptoms that are not directly related to the thyroid gland.

Thyroid-associated orbitopathy (Graves orbitopathy [GO]) is a condition associated with ocular symptoms caused by autoimmune inflammation of the soft tissues of the orbit in the course of GD, leading to a temporary or permanent damage to the eye. Patients may develop a severe form of progressive ophthalmopathy with infiltrates and edema, which is associated with particularly high risk of permanent complications.

Clinical FeaturesTop

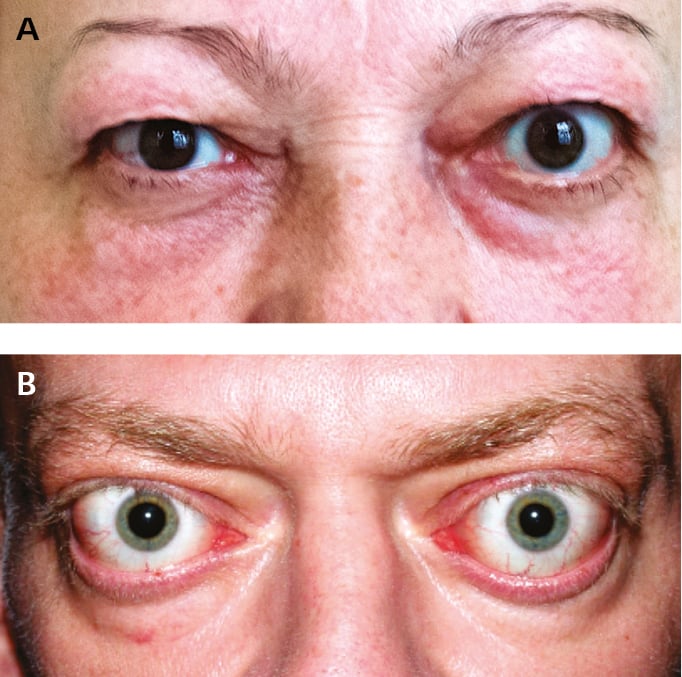

1. Clinically overt or moderately symptomatic hyperthyroidism (see Thyrotoxicosis); in the elderly cardiac symptoms may be the only manifestation of the condition. Usually GD presents with a vascular goiter associated with a typical vascular bruit; exophthalmos may be seen (Figure 6.7-1; but overt orbitopathy is not a necessary diagnostic criterion for GD). Less commonly there are signs and symptoms of autoimmune dermatitis, including pretibial myxedema (thyroid dermopathy, a pathognomonic but rare sign) and thyroid acropachy (clubbing [very rare]).

2. GO develops simultaneously with hyperthyroidism or within 24 months from its onset. It may precede other symptoms of hyperthyroidism and rarely is the only symptom of GD. In exceptional cases it may be associated with hypothyroidism or euthyroidism. Patients with GO report eye pain and burning, tearing, reduced visual acuity, sensation of grittiness, photophobia, and diplopia. The findings on clinical examination include exophthalmos, palpebral and periorbital swelling, conjunctival injection, and impaired ocular movement. The risk of sight loss is related to corneal ulcerations caused by incomplete eyelid closure and to possible optic nerve compression (with an early symptom of impaired color vision).

DiagnosisTop

GD may manifest as overt or subclinical primary hyperthyroidism (see Thyrotoxicosis). Patients can be asymptomatic or, more commonly, present with symptoms of hyperthyroidism.

1. Laboratory tests:

1) Low serum TSH concentrations and high (less commonly normal) serum free thyroid hormone concentrations (usually free thyroxine [FT4] levels are sufficient for diagnosis; in patients with normal FT4 levels serum free [FT3] or total triiodothyronine concentrations should be assessed). In patients in remission the hormone test results are normal.

2) Elevated TRAb levels confirm the diagnosis of GD (they should preferably be assessed before starting antithyroid therapy or within the first 3 months of treatment). The performance of TRAb assays in the differential diagnosis of hyperthyroidism is excellent, with sensitivity and specificity in the upper 90% range. Normalization of TRAb levels indicates immunologic remission of the disease.

3) Serum antibodies to thyroperoxidase (TPOAb) and antibodies to thyroglobulin (TgAb) (see Thyrotoxicosis).

4) Other laboratory test results are as in hyperthyroidism (see Thyrotoxicosis).

2. Imaging studies: Thyroid ultrasonography is not needed to confirm GD; however, when done, it reveals hypoechogenic thyroid parenchyma with increased vascularity. The thyroid gland is usually enlarged. Presence of nodules does not exclude GD. Thyroid scintigraphy with radioactive iodine (RAI) shows elevated and diffuse thyroid uptake of iodine; normal uptake of iodine in the setting of suppressed TSH values is also considered abnormal and suggestive of GD. Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the orbits (contrast enhancement is not necessary) in patients with active and severe ophthalmopathy allows for the evaluation of the soft tissues of the orbit, its bone walls (important for planning surgical decompression), and thickening of the extraocular muscles. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbits allows for the assessment of edema or fibrosis of the extraocular muscles.

Diagnostic Criteria for Graves Disease

The diagnosis of GD is confirmed in patients with:

1) Overt or subclinical hyperthyroidism and elevated TRAb levels.

2) Hyperthyroidism with concomitant thyroid-associated orbitopathy and evident involvement of the orbital soft tissues (Figure 6.7-1) or with thyroid dermopathy (Figure 6.7-3).

3) Hyperthyroidism with increased RAI uptake, mainly diffuse, in thyroid scintigraphy if TRAb levels cannot be measured or are negative.

4) Isolated thyroid-associated orbitopathy with elevated TRAb levels.

Isolated elevation of TRAb levels is not sufficient for the diagnosis of GD (it may occur in relatives of patients with GD who do not develop the disease themselves).

Diagnostic Criteria for Graves Orbitopathy

It is important not only to recognize inflammation of the orbital soft tissues and establish the diagnosis of GO but also to determine whether the severity of symptoms warrants treatment initiation (this requires a complete ophthalmologic examination and in many cases also imaging of the orbits).

A classification of GO with respect to the activity of autoimmune inflammation (according to the 2016 consensus statement of the European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy [EUGOGO]):

1) Sight-threatening GO: Optic neuropathy and/or corneal breakdown; significant visual disturbances are present. This category warrants immediate intervention.

2) Moderate to severe GO (Figure 6.7-1): One or more of the following are present: eyelid retraction ≥2 mm, moderate or severe involvement of the orbital soft tissues, exophthalmos ≥3 mm above normal for the patient’s age and sex, constant or intermittent diplopia.

3) Mild GO (Figure 6.7-1): Mostly mild restrictions of daily functioning with ≥1 of the following symptoms or signs: minor eyelid retraction <2 mm, mild involvement of the orbital soft tissues, exophthalmos <3 mm, transient or no diplopia, corneal exposure responsive to lubricants.

Evaluation of the activity of GO based on features of inflammation: Clinical Activity Score (CAS) corresponds to the total number of symptoms (symptom present, score 1; symptom absent, score 0):

1) Spontaneous retrobulbar pain.

2) Pain on attempted up or down gaze.

3) Redness of the eyelids.

4) Redness of the conjunctiva.

5) Swelling of the eyelids.

6) Inflammation of the caruncle, plica, or both.

7) Conjunctival edema.

A CAS score ≥3/7 indicates active GO.

Differential Diagnosis of Hyperthyroidism

Differential diagnosis of GD and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: Figure 6.7-2 and Table 6.7-2. Elevated TRAb levels confirm an active autoimmune process in GD.

Differential Diagnosis of Graves Orbitopathy

Ocular signs and symptoms accompanying nonautoimmune hyperthyroidism (TRAb levels are the key parameter). If proptosis is unilateral, differentiate with orbital lymphoma, metastasis, IgG4-related disease, or granuloma (pseudotumor of the orbit).

TreatmentTop

Treatment focuses on controlling the symptoms of hyperthyroidism and orbitopathy.

The primary goal is to achieve euthyroidism as soon as possible, and then a joint decision should be taken with the patient to plan the subsequent treatment strategy. If pharmacotherapy is the principal treatment modality, try to achieve and maintain immunologic remission. Normalization of TRAb levels is a good prognostic factor. Similarly, reduction of goiter size and resolution of features of a vascular goiter (due to the reduction of the stimulating effect of TRAb and resolution of lymphocytic infiltrates) are good prognostic factors as indirect signs of immunologic remission. Recurrence of hyperthyroidism is usually an indication for definitive treatment with RAI or surgery, but prolonged medical treatment may be considered if there are contraindications to definitive treatment or in case of strong preference of the patient.

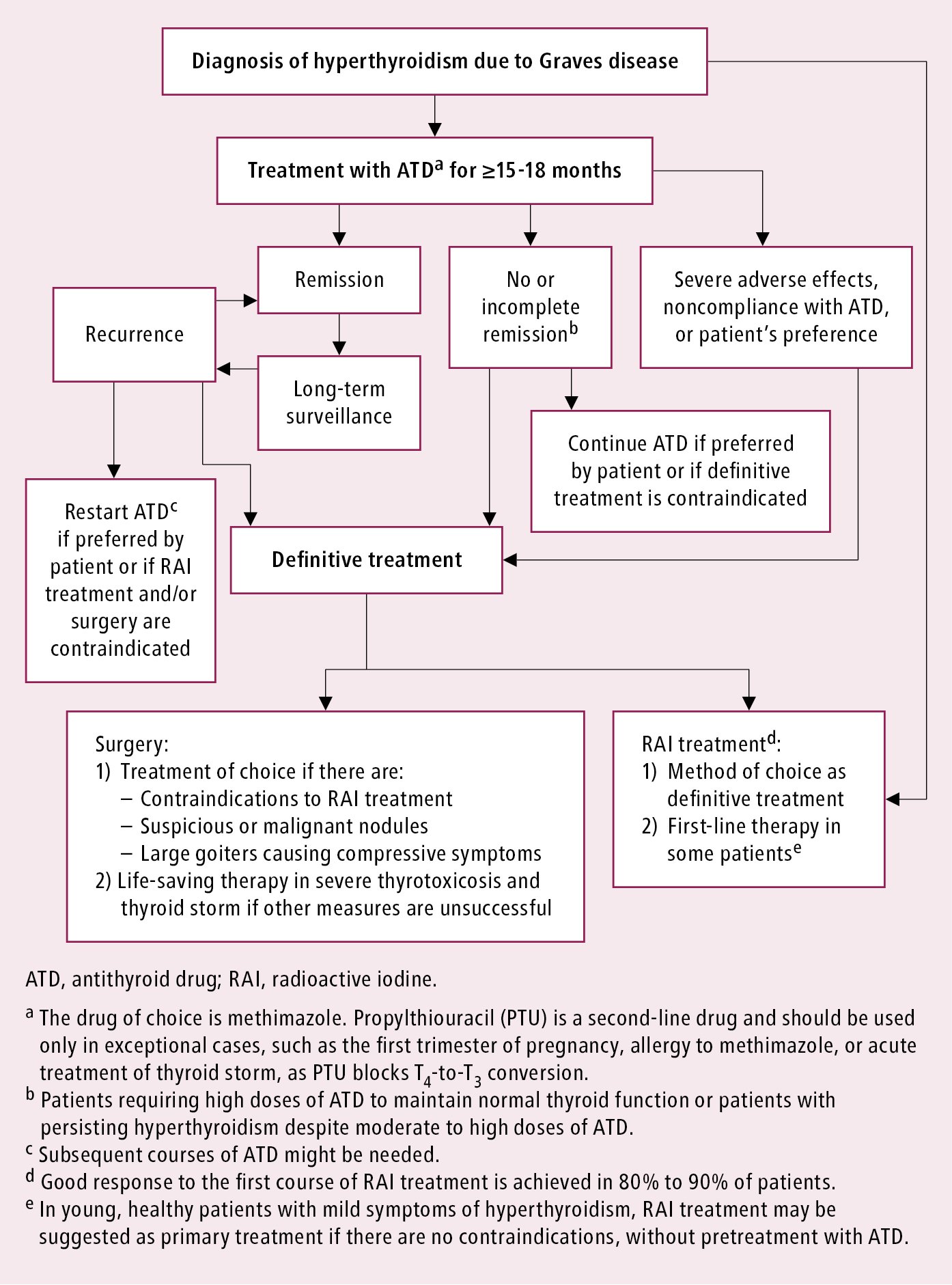

Basic principles of hyperthyroidism management in GD: Figure 6.7-2.

Principles of hyperthyroidism treatment: see Thyrotoxicosis.

The optimal duration of pharmacologic treatment is ~18 months and ≥12 months are usually necessary to achieve a durable immunologic remission. Patients can also receive long-term therapy with methimazole or propylthiouracil (PTU) if GD remission has not been achieved in 18 months.

1. Regimens of antithyroid treatment in GD: Treatment with methimazole, the drug of choice (dosage: see Thyrotoxicosis), should be continued until the patient is euthyroid (~3-6 months); the dose is usually 20 mg/d, and then it is gradually tapered to the maintenance dose (see above; to be continued for ~18 months or longer). PTU is a second-line drug due to rare reports of serious liver injury and deaths. It should be used only in exceptional cases such as in the first trimester of pregnancy and in acute treatment of thyroid storm, since it blocks T4-to-T3 conversion. It is also used in exceptional cases in patients with allergy to methimazole in whom antithyroid treatment is required (in 50% of cases there is no cross-reactivity). Dosage: see Thyrotoxicosis. The time to achieving euthyroidism is usually longer.

2. Features suggestive of the need for long-term pharmacotherapy:

1) Lack of hormonal remission: Despite antithyroid treatment levels of thyroid hormones do not normalize or increase again on attempts of dose reduction.

2) Lack of initial immunologic remission: Persistently elevated TRAb levels after 6 months of drug therapy despite resolution of hyperthyroidism symptoms.

3) Lack of durable immunologic remission: Elevated TRAb levels after 12 months of treatment indicate a high risk of recurrence (75%-90%) despite euthyroidism.

4) Recurrence of hyperthyroidism after achieving hormonal and immunologic remission. A true relapse is diagnosed when the remission has lasted ≥1 year after discontinuation of treatment.

3. Pharmacologic pretreatment before definitive therapy:

1) Pretreatment before surgery should last 4 to 6 weeks (a minimum of 2 weeks). The preferred drug is methimazole because of the shorter time required to achieve euthyroidism; it should be discontinued after surgery.

2) Pretreatment before RAI therapy should last 1 to 3 months. The preferred drug is methimazole because of the lower inhibition of thyroid sensitivity to ionizing radiation (methimazole should be discontinued 5 to 7 days before RAI therapy and restarted 5 to 7 days after the therapy, as necessary [see Thyrotoxicosis]).

4. Pharmacologic management during pregnancy: Specialist consultation is required, if feasible. Consider the following principles:

1) Do not use antithyroid agents between 6 and 10 weeks of pregnancy, if possible.

2) After confirmation of pregnancy in a woman who is in euthyroid state during treatment with low-dose methimazole (≤5-10 mg/d) or PTU (≤50-100 mg/d), the drug may be withheld taking into account the course of the disease, duration of current treatment, results of recent hormonal tests, and TRAb concentration. After withholding the drug, the patient should be followed clinically and biochemically (TSH and FT4) every 4 weeks throughout the pregnancy.

3) If an antithyroid drug is necessary, use PTU before pregnancy and in the first trimester. After 16 weeks (second trimester) of pregnancy methimazole is preferred.

4) Use antithyroid drugs at the lowest effective dose to keep FT4 at or just above the upper limit of normal (ULN), as the drug crosses the placenta and may affect the function of the fetal thyroid gland.

5) Monitor serum TSH and FT4 levels initially every 4 weeks throughout the pregnancy. GD frequently improves in the third trimester. In pregnant women propranolol may also be used, but only if necessary and for as short as possible.

Principles of hyperthyroidism treatment: see Thyrotoxicosis.

The method of choice in the definitive treatment of hyperthyroidism in GD. In approximately three-fourths of patients one administration of 131I is sufficient, whereas in the remaining cases a repeated dose is required, usually after 6 to 12 months. In severe or moderate active GO, RAI treatment is not suggested as a therapy for GD due to the risk of worsening GO symptoms.Evidence 1Weak recommendation (downsides likely outweigh benefits, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness (evidence from trials using radioactive iodine among patients with mild Graves orbitopathy suggests that the use of radioactive iodine for active severe Graves disease could carry a significant risk for adverse effects. The possible harm is valued very highly). Tallstedt L, Lundell G, Tørring O, et al. Occurrence of ophthalmopathy after treatment for Graves' hyperthyroidism. The Thyroid Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1992 Jun 25;326(26):1733-8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206253262603. PMID: 1489388. In mild to moderate active GO concomitant glucocorticoid therapy is suggested to accompany 131I treatment (because of the risk of transient exacerbation)Evidence 2Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to inconsistency and imprecision. Bartalena L, Marcocci C, Bogazzi F, et al. Relation between therapy for hyperthyroidism and the course of Graves' ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 1998 Jan 8;338(2):73-8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801083380201. PMID: 9420337.: prednisone 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg/d starting from day 1 to 3 of RAI administration and continued for 1 month; then the dose should be gradually tapered to discontinuation within ≤3 months. Because smoking exacerbates GO, patients with GO should be recommended to quit.

An unequivocal indication for surgery is the presence of a suspicious or malignant nodule (the risk of thyroid cancer in GD is 2%-7% lifelong, similar to other forms of nodular goiter). Surgery is preferred in patients with concomitant severe orbitopathy, allergy to thionamides, those who are not candidates for RAI therapy, or those with large goiters (>80 mL) causing compression symptoms, particularly if the goiter contains large areas with no iodine uptake. The volume of fragments of the thyroid gland remaining after surgery strongly correlates with the risk of recurrence of GD, which more and more often is a rationale for performing total or near-total thyroidectomy; however, due to a higher risk of long-term complications, this approach is not universally accepted. An unavoidable sequela of the surgery is hypothyroidism (at least subclinical), requiring hormone replacement therapy. Other potential complications of surgery include transient or permanent hypoparathyroidism, recurrent or superior laryngeal nerve palsy, wound infection, and keloid formation.

Treatment of Thyroid-Associated Orbitopathy

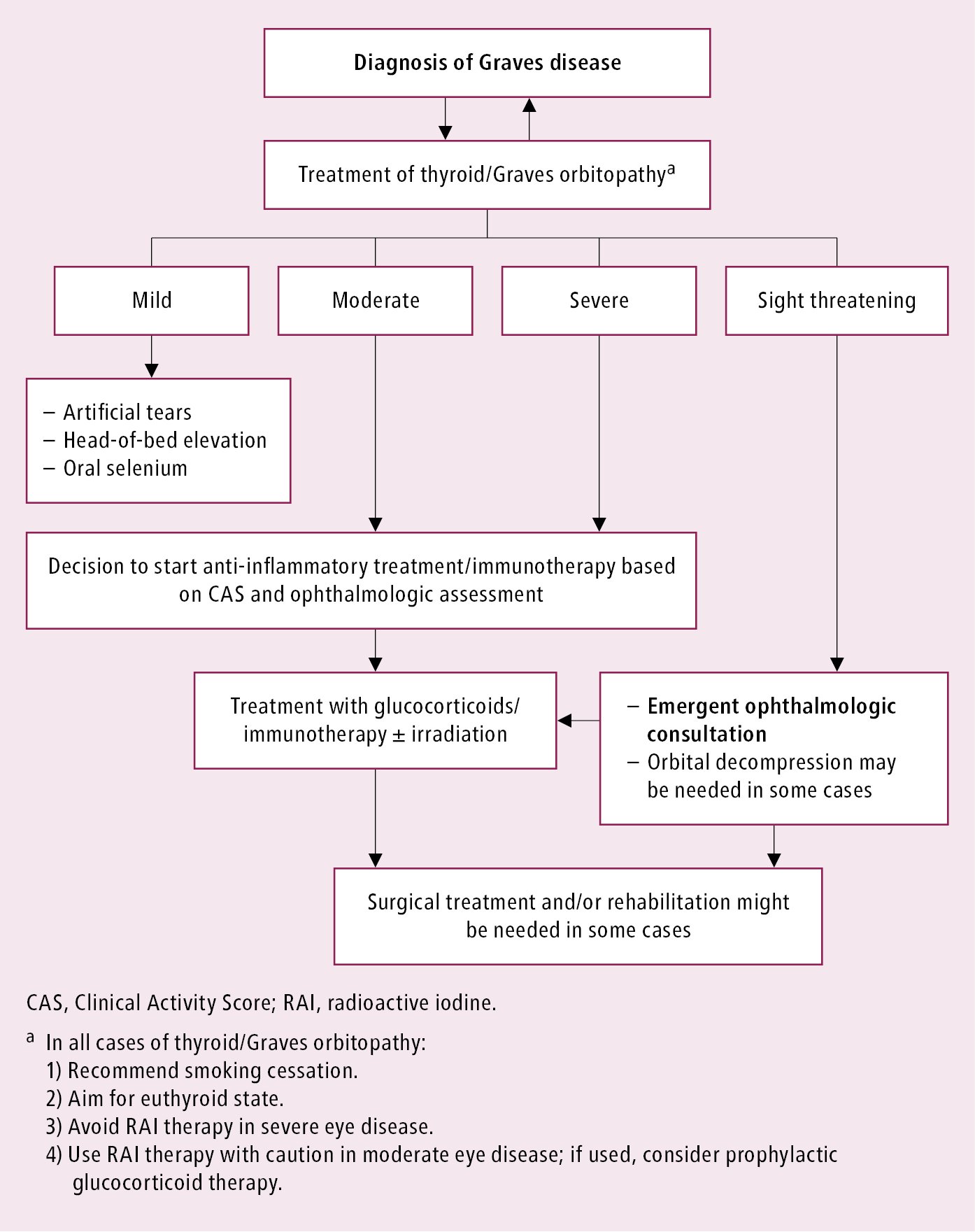

Durable effects cannot be achieved without effective treatment of hyperthyroidism. Achieving remission of hyperthyroidism alone may result in improvement or remission of GO within 2 to 3 months. Anti-inflammatory treatment with glucocorticoids should be started early when the patient is still in the active inflammatory phase. An indication may be a rapid development of symptomatic GO. Management depends on the severity of orbitopathy:

1) Sight-threatening orbitopathy: Start IV glucocorticoids immediately, consider orbital decompression surgery.

2) Moderate to severe orbitopathy: Start immunosuppressive treatment with glucocorticoids (in active disease; CAS ≥3/7) or consider surgery (if the disease is not active).

3) Mild orbitopathy: Symptoms do not affect daily activities and do not warrant immunosuppression or surgery. Symptomatic treatment, including artificial tears, ointments, and dark glasses, is often enough to relieve eye symptoms. There is some evidence that selenium (100 microg bid) for 6 months improves symptoms in patients with mild orbitopathy; this approach has been recommended by the European Thyroid Association.Evidence 3Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity. Kahaly GJ, Riedl M, König J, Diana T, Schomburg L. Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Trial of Selenium in Graves Hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Nov 1;102(11):4333-4341. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01736. PubMed PMID: 29092078. Marcocci C, Kahaly GJ, Krassas GE, et al; European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy. Selenium and the Course of Mild Graves’ Orbitopathy. N Engl J Med. 2011 May 19;364(20):1920-31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012985. PMID: 21591944.

In moderate or severe cases an ophthalmologist should be consulted.

Basic principles of GO management: Figure 6.7-3.

In case of threatened vision, use glucocorticoids immediately (eg, methylprednisolone 0.5-1 g IV for 3 consecutive days). In moderate to severe GO glucocorticoids are the first-line drugs and should be started after careful evaluation and confirmation of disease activity. IV pulse glucocorticoids are more effective and better tolerated than oral glucocorticoids in moderate to severe GO; thus, IV pulses of glucocorticoids are recommended as the treatment of choice.Evidence 4Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision. Kahaly GJ, Pitz S, Hommel G, Dittmar M. Randomized, single blind trial of intravenous versus oral steroid monotherapy in Graves' orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Sep;90(9):5234-40. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0148. Epub 2005 Jul 5. PMID: 15998777. Methylprednisolone pulses are given IV in a cumulative dose of 4.5 to 5 g (eg, 500 mg IV weekly for 6 weeks, then 250 mg IV weekly for 6 weeks). When IV glucocorticoids are contraindicated, oral prednisone is given at 1 mg/kg/d for 6 to 8 weeks, then the dose is tapered to discontinuation at 3 months.

Teprotumumab is an insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) inhibitor. It was approved in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2020 in patients with active moderate and severe orbitopathy.Evidence 5Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness.Douglas RS, Kahaly GJ, Patel A, et al. Teprotumumab for the Treatment of Active Thyroid Eye Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan 23;382(4):341-352. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910434. PMID: 31971679. The use of this therapy is limited by its cost, which may well exceed $100,000.

An optional method. The combination of glucocorticoids and radiotherapy yields better and longer-lasting effects than either method used alone. Diabetic retinopathy is the only contraindication.

The only method of treatment of long-term sequelae of orbitopathy after resolution of active disease. It is frequently a multistep procedure including orbital decompression, treatment of strabismus resulting from fibrosis of the extraocular muscles, and surgical procedures on the eyelids. Urgent orbital decompression surgery should be considered in patients with symptoms of optic nerve compression and when 1-week to 2-week intensive immunosuppressive treatment is ineffective.

PrognosisTop

1. Hyperthyroidism: Sometimes spontaneous remissions are observed in patients with untreated hyperthyroidism due to GD, but complications may develop earlier (see Thyrotoxicosis). Pharmacologic treatment alleviates symptoms of thyrotoxicosis and accelerates remission but recurrence rates are ~50% to 70%. In the majority of patients TRAb levels normalize after ~6 months of treatment, but this does not guarantee a durable remission. The risk of recurrence is higher in male patients and in patients <20 years of age, in patients with orbitopathy, as well as in patients with large goiters, high TRAb levels, and high baseline FT3 values, FT4 values, or both. Hypothyroidism is always observed after surgery and is very frequent (a desired outcome) after effective RAI therapy; it may also develop after long-term pharmacologic treatment of GD.

2. GO: Spontaneous remissions with no long-term sequelae may be observed in untreated patients, particularly with mild orbitopathy. Nevertheless, in patients with severe active GO the risk of permanent damage to the orbital structures (disturbances of eye movements and visual impairment or even loss of vision) is high, particularly in the severe form of progressive ophthalmopathy with infiltrates and edema. If treatment is started early (in active disease), serious sequelae can often be avoided. If exophthalmos is advanced and significant involvement of the soft tissues and extraocular muscles is present, or in cases of corneal involvement or optic nerve compression, the risk of permanent damage to the eye and alteration of the patient’s appearance is high. Strabismus and exophthalmos are surgically corrected after remission of active disease is achieved.

FiguresTop

Figure 6.7-1. Thyroid-associated orbitopathy. A, mild orbitopathy (eyelid retraction, mild right eye proptosis without other symptoms affecting soft tissues). B, overt orbitopathy. Figure courtesy of Dr Ewa Bar-Andziak.

Figure 6.7-2. Graves disease. Basic principles of hyperthyroidism management.

Figure 6.7-3. Graves disease. Basic principles of thyroid/Graves orbitopathy management.