Rihal, CS, Naidu SS, Givertz MM, et al. 2015 SCAI/ACC/HFSA/STS Clinical Expert Consensus Statement on the Use of Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices in Cardiovascular Care. JACC. 2015 May 65(19):e7-26. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.036. PMID: 25861963.

Ventricular assist devices (VADs) can be used for both short-term and long-term mechanical circulatory support (MCS). In general, they are implanted to support or replace one of the ventricles. The right ventricular assist device (RVAD) supports pulmonary circulation and the left ventricular assist device (LVAD) provides peripheral perfusion in the case of significantly reduced left ventricular output. Biventricular implantations (biventricular assist devices [BiVADs]) are rare but can be considered as a bridge to transplant (BTT).

Early VADs generated pulsating flow but due to frequent thromboembolic complications they have now been replaced with safer continuous-flow pumps, where blood flow is forced into the pump by a centrifugal rotor suspended in an electromagnetic field. This does not generate friction during blood flow and reduces the frequency of complications.

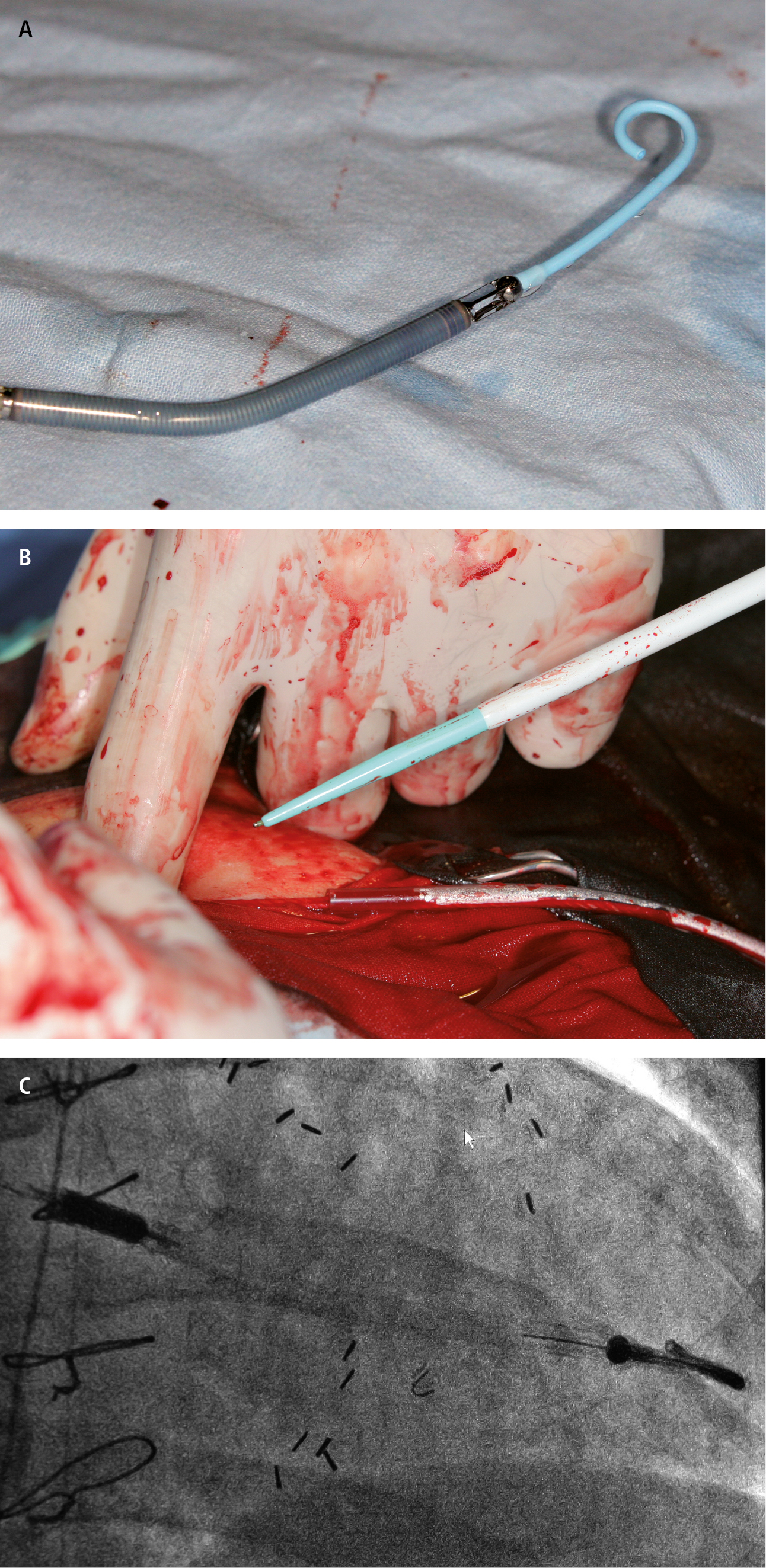

Percutaneous VADs (pVADs) (eg, Impella [Figure 21.10-1], TandemHeart) can be implanted for short-term MCS in cardiogenic shock. Compared with the intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), better blood pressure and organ perfusion results are obtained. However, there is no improvement in short-term survival, and implantation of percutaneous LVAD is associated with a higher risk of access site bleeding and limb ischemia. These devices can also be used as a protective measure in high-risk cases of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and may be used in conjunction with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) to reduce left ventricular wall stress.

Long-term MCS is usually managed with VADs, and LVADs are commonly implanted as destination therapy worldwide (>70% implantations according to the 2019 Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs registry report). The device is implanted surgically via sternotomy or minithoracotomy and placed within the pericardial sac. It collects blood from the left ventricle and pumps it to the ascending aorta, to which it is connected by a vascular graft. The device’s power cable (so-called driveline) is led outside through the abdominal wall to the batteries carried in a special bag, which allows patients to move freely.

The current 2-year survival rates in patients using the latest continuous-flow LVADs are similar to those for heart failure (HF) (75%-85%), although several adverse events can impact the quality of life. Although the novel fully magnetically levitated centrifugal-flow LVAD has significantly reduced pump-related thrombosis, other complications remain common, including stroke, gastrointestinal bleeding, and driveline infections.

A long-term MCS program requires a dedicated team that can provide instructions on LVAD handling to the patient and family members. Patients are discharged home, routinely monitored by the implantation center using telemedical systems, and hospitalized when required. Permanent anticoagulation therapy is necessary after VAD implantation. Vitamin K antagonists are routinely used, with an international normalized ratio (INR) target between 2.0 and 3.0 recommended by the European Association of Cardiothoracic Surgeons consensus. Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) is routinely administered according to device specifications. The use of non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants is currently not recommended. Frequent INR checks using home monitoring is considered the best management to achieve effective anticoagulation.

IndicationsTop

In general, patients can be considered for long-term VAD implantation if they have persistent symptoms of severe HF despite optimal medical and device therapy and ≥1 of the following: left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <25%, ≥3 HF hospitalizations in previous 12 months, dependence on IV inotropes or short-term MCS, progressive end-organ dysfunction due to HF.

Based on the 2021 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic HF, long-term MCS with VADs is indicated as destination therapy when cardiac recovery has not been achieved with short-term MCS and contraindications to heart transplant (HT) are present. Long-term LVAD implantation should be also considered in patients with potentially reversible contraindications to HT (bridge to candidacy [BTC]) and in patients at high risk of cardiac death who are eligible for HT until a donor organ becomes available (bridge to transplant [BTT]).

ContraindicationsTop

Contraindications were established by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation early in the VAD implantation era and include:

1) Limited life expectancy (including advanced age [>80 years] and active malignancy).

2) Severe comorbidities precluding an acceptable outcome that are potentially not resolved after restoration of proper end-organ perfusion.

3) Active severe bleeding.

4) Active infection.

5) Anticoagulation intolerance.

6) Severe independent right heart failure (for LVADs).

ComplicationsTop

The introduction of fully magnetically levitated centrifugal-flow LVADs has significantly reduced initial rates of postimplantation complications. According to the ELEVATE registry data on 2-year outcomes, complications include driveline infection (29.6%), sepsis (15.1%), ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke (10.2%), gastrointestinal bleeding (9.7%), pump-related thrombosis (1.5%), and hemolysis (0.6%).

FiguresTop

Figure 21.10-1. Implantation of a mechanical circulatory support system (Impella) through vascular access. A, miniaturized system before implantation. B, system implantation via the femoral artery. C, correctly positioned device.