This transcript was revised on April 23, 2020. References were added on May 1, 2020.

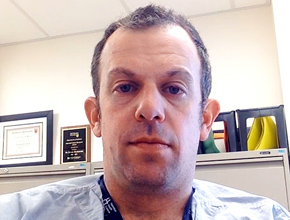

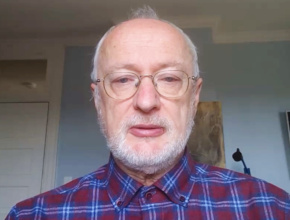

Dr Gordon Guyatt, distinguished professor in the Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact at McMaster University and one of the founders of evidence-based medicine, discusses with Dr Roman Jaeschke the rationale behind making treatment decisions in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

References

Ye Z, Rochwerg B, Wang Y, et al. Treatment of patients with nonsevere and severe coronavirus disease 2019: an evidence-based guideline. CMAJ 2020. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200648; early-released April 29, 2020.Roman Jaeschke, MD, MSc: Good afternoon. Welcome to another edition of McMaster Perspective. We are interviewing one of our favorite—if not the favorite—guests, Doctor Gordon Guyatt, who not only coined the term evidence-based medicine but also patient-important outcomes. Obviously, we will be talking about patient-important outcomes in the context of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Doctor Guyatt, I believe you are involved in a number of clinical practice guidelines. Could you tell us a few words about that?

Gordon Guyatt, MD, MSc: I think what you’re interested in is my involvement with one COVID-19 practice guideline, right?

Roman Jaeschke: That is correct.

Gordon Guyatt: The story behind this is that I have a PhD student from China who 2 or 3 months ago, when the [virus] was in China and had not spread, said he wanted to do things for his home country. He said, “What I’d like to do for my home country is have a guideline about treating COVID-19.” This guy is an impressive networker, and we soon had 15 top Chinese experts, many of whom were in the front lines treating COVID-19, as well as other experts from around the globe to do this guideline.

We launched a clinical practice guideline about convalescent plasma, steroids, and antiviral drugs, which we now have completed. We’ve done 3 substantial systematic reviews and produced a guideline according to what we believe are trustworthy standards for creating guidelines. It’s now under consideration by the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ). [An early-release version was published on the CMAJ website on April 29, 2020.]

Roman Jaeschke: I understand you prepared these practice guidelines. What’s your conclusion: is there anything that we should start using on a wide scale?

Gordon Guyatt: No. The evidence is very low quality as far as benefits are concerned for every agent and mostly low quality for harms. The treatments probably have harms; almost everything we can do has harms. As far as we know, now—other than perhaps steroids in critically ill patients—everything else is uncertain.

Roman Jaeschke: Are these treatments still at the stage where they all should be tested in properly done clinical experiments?

Gordon Guyatt: There may be more merits of testing one versus the other, but they’re all potential for being tested in randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Roman Jaeschke: OK. So far we have interviewed a few people and everybody believes in using those drugs in RCTs. But around the world there are different ways of handling this situation. People also have to deal with anxieties, expectations, occasionally anger at no specific therapy. It’s not that every physician has an easy opportunity to enroll people in RCTs. How should they behave when faced with requests for “something against the virus”?

Gordon Guyatt: I’ve not yet been in this situation. It seems challenging to me. I feel like I’d need to be in this situation to know for sure.

If you’re being honest, you say, “I have a list of 5, 6, or 7 treatments that are potentially beneficial, but all come with harms. We don’t know if any of them are any good. I wouldn’t know which one to give you. Maybe they work, but probably they don’t. And they all come with harms. If you want to choose one, I can discuss them with you. But the bottom line will be that I’m going to be of little help, because the evidence supporting any of them is very low quality. We’re really uncertain. If I were guessing, none of them work. Maybe they do, but my guess would be none of them work. They all come with harms. We’ll have to decide what to do.”

Roman Jaeschke: I can just hope that when we repeat our conversation maybe 2 or 4 weeks from now we’ll have a little bit more optimistic message. It sounds like for the moment you’re mostly in favor of supportive treatment plus participation in RCTs. Is that correct?

Gordon Guyatt: That is absolutely correct.

Roman Jaeschke: I heard an opinion that I want to share with you. The opinion is that at the time of pandemic, when we’re dealing with a potentially deadly disease and you are in a group which has a very poor prognosis, it would be unethical not to give medications that potentially could be useful. It would be unethical to leave a person without treatment. What’s your reaction to such statements?

Gordon Guyatt: The first thing is that it is a complete mischaracterization to say we’re leaving people without treatment. This is a really problematic mischaracterization.

In the people who have moderate disease, we give antibiotics—because they may have a superinfection with bacteria—we give fluids, we give oxygen, we give antipyretics, things to bring down the fever, we give nursing care. We give a whole series of supportive interventions. So it is a complete mischaracterization to say that we’re giving people nothing. We’re giving people a great deal to get them through the illness.

If they get critically ill, we have—which as a critical care physician you know better than I do—all sorts of other treatments we give them to maintain their blood pressure, maintain the optimal fluid status, the optimal ventilation, and so on. To characterize things as “doing nothing” is a bizarre mischaracterization. We’re doing a great deal to get them through the illness.

Roman Jaeschke: It may be bizarre, but at the same time I repeatedly hear that that’s what is happening. People demand some sort of specific treatment.

Gordon Guyatt: Yes, but do they understand what they’re asking for? I don’t think they do.

Roman Jaeschke: I think we, as human beings, behave frequently in a way we don’t understand the consequences of what we’re doing.

Gordon Guyatt: Absolutely. For sure. But let us distinguish between “we understand and we’re still behaving irrationally” and “we don’t understand.” I think we should distinguish between those two situations.

The accurate characterization is, “We have 5 medications or more that we could give you. We don’t know if any of them work. As a matter of fact, probably none of them work. Maybe they do, but it’s unlikely any of them work. All have adverse effects. We can give you supportive care, very aggressive supportive care, or we can subject you to unknown benefit with almost certain side effects.” This is the accurate characterization of the situation. People can behave rationally or irrationally once they understand the situation, but the first thing is to understand the situation.

Roman Jaeschke: There is a problem. In the media you see stories about hydroxychloroquine. In the past 24 hours the stock market has moved because somebody recorded something about remdesivir. Now azithromycin is running out of stock. It’s kind of a situation where objectively phenomena exist, even if we don’t agree with them. Your comments?

Gordon Guyatt: Distorted, misleading media presentations exist, which cause big problems and which will lead potentially to big increased toxicity, increased resistance to drugs, and unavailability of drugs to people who really need them for indications for which they’ve been shown to be effective. All sorts of things were happening that have clear adverse consequences and uncertain or likely no benefits. Very problematic.

Roman Jaeschke: We’ll have to live with the patient-important outcomes of anxiety, emotions, and anger, then.

Gordon Guyatt: Wait a minute. We need to deal with those appropriately. We might need to talk with patients for an hour about it. But to say, “We’ll deal with your anxiety by throwing a drug at you that is probably useless and certainly harmful,” that is a poor way to deal with patient anxiety.

Roman Jaeschke: My own anxiety dictates me a statement that I hope in 2 or 4 weeks we’ll have some treatment that will be useful, helpful…

Gordon Guyatt: Or we’ll find out they’re all useless, which is more likely.

Roman Jaeschke: All right. With this optimistic statement let’s finish for now, and I’ll invite you in a week from now to see whether something’s changed. Thank you.

Gordon Guyatt: I will be delighted to talk to you.

English

English

Español

Español

українська

українська