Aristeidis Katsanos, MD, PhD, vascular neurologist, assistant professor of medicine in the Faculty of Health Sciences at McMaster University, investigator at the Population Health Research Institute (PHRI), and fellow of the Canadian Stroke Consortium (CSC), meets with James Douketis, MD, expert in thromboembolism, to discuss the use of DAPT in ischemic stroke.

For a Publications of the Week article discussing DAPT following ischemic stroke, click here.

James Douketis, MD: Hello everybody. My name is Dr Jim Douketis. I’m one of the internists here at McMaster University. We’re joined today by Dr Aristeidis Katsanos, who is an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine and a stroke neurologist at the Hamilton Health Sciences, to provide a McMaster perspective on a recent article investigating the use of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in patients with ischemic stroke.

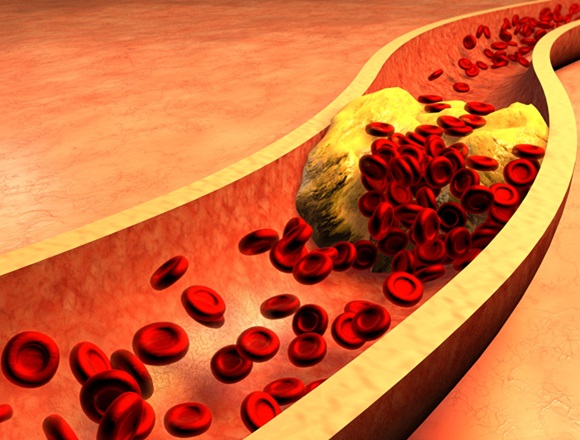

Aristeidis, welcome, and perhaps we can start by you giving us a bit of background as to the use of DAPT in ischemic stroke. We’re familiar with it in patients with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), but perhaps you can provide a bit of background about its use and development in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Aristeidis Katsanos, MD, PhD: Yes, thank you so much, Jim, for the kind invitation. It’s always a pleasure to discuss with you about the recent trials in stroke and advances in secondary stroke prevention.

I think it all started from cardiology. We did see, as neurologists, the success of DAPT in cardiology, so we wanted to do the same in stroke. One of the first big trials that [researchers] tried to do was the MATCH (Management of Atherothrombosis with Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients) trial including patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), but it used—relatively looking now, with the very recent data—a very broad period for inclusion. It was patients within 3 months. They were randomized to DAPT or monotherapy. Unfortunately, it was a neutral trial. There was no significant reduction in the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and there was also an increased risk of bleeding.

We were not very satisfied with that. We weren’t able to replicate the good results that we have seen in myocardial infarction (MI) in the cardiology literature, but the first sparkle happened in 2013, coming again from China with the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-risk patients with Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events) trial. It was a big trial. This time they focused more on the population. First, they included patients with minor stroke. They had a scale. We have a scale, as stroke neurologists, which is called the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). They included patients with minor strokes, so they had a score of ≤3 on this scale. More importantly, [patients] should have the symptoms of minor stroke or TIA within 24 hours. These patients were randomized to DAPT with clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin monotherapy. DAPT was given for 21 days. Good results: we found a reduction in the risk of stroke at 90 days and there was no increase in the risk of bleeding. When the results were announced, there was a lot of enthusiasm but also a lot of skepticism, because the results were coming only from the Chinese population. I would say some people were hesitant to implement those results into clinical practice.

In 2018 there was a similar trial done in the Western countries. This is the POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) trial, again using clopidogrel with a higher loading dose of 600 mg and [longer] duration of treatment of 90 days compared with aspirin. Again, they included patients with minor ischemic stroke with an NIHSS [score] of ≤3 or TIA and they had to be recruited within 12 hours. The primary end point was MACEs. There was a reduction in the primary end point and there was also a reduction in stroke. In that trial we did see a high risk of major hemorrhages, but this trial was really important as it confirmed the results of the CHANCE trial and provided reassurance to us as stroke neurologists that DAPT is in fact beneficial for people with minor ischemic stroke or TIA presenting within a time frame of 12 to 24 hours.

That’s the background that we had up until recently, Jim.

James Douketis: Well, thank you. That’s a very comprehensive summary. There was a foundation for considering DAPT and the trial that we’re talking about right now looked at an extended window to initiate DAPT and it involved over 6000 patients. It was a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. It showed some benefits and a little bit of harm, so maybe you can elaborate on what your views of this study are in terms of the overall strengths and perhaps the weaknesses as well.

Aristeidis Katsanos: Yeah, for sure. This is one of the studies you really like to see because it goes with your clinical practice. I’ll be honest, people who are calling me from the emergency [department]—[whose patients] had a minor stroke or a TIA and they were just outside of the window of the 24 hours—I always advise [them] that there is a benefit even [beyond] 24 hours, and there was an assumption we didn’t have the evidence up until recently with this trial coming down from China. In this trial, again, the same rationale, so it was minor ischemic stroke. The NIHSS score was a little bit higher—they allowed up to 5 points—so we were able to include a little bit broader population or TIA.

The other thing is that they specified that the presumed mechanism of the stroke was atherosclerosis, so they also took some coronary imaging into account to enroll those patients. But the most important [fact] is that they allowed for a pretty good time frame, which was 72 hours and we know that most of the patients with stroke are going to present in that time window. Most of them in Canada present within 24 hours, but in other parts of the world there may be the late presentation, so these 72 hours didn’t make any difference indeed.

They found that there was a benefit in the primary end point, which was the reduction in the risk of stroke, with the downside, as you said—the increase in the risk of major bleeding, of course. This is really important because it confirms the results of CHANCE and POINT, but more importantly it gives us a little bit more flexibility as clinicians to use DAPT in a little bit higher NIHHS score, in patients with more disabling deficits, and also to be a little bit more relaxed about the time window.

James Douketis: OK. So, a good study and favorable results both in terms of net therapeutic benefit: ~2% absolute risk reduction in ischemic events and only a 0.5% increase in bleeding events.

Now, as you said, the population of the study was Han Chinese. Do you think we need another study to replicate these results in a broader population in a similar way that it was done after the CHANCE trial or do you think these results are robust enough that they can be generalizable to other populations? I should point out it seemed that the majority of patients, ~65% or so, were men. How do you look at it just from a generalizability standpoint?

Aristeidis Katsanos: Yeah, that’s an excellent question. As you said, there are limitations to the study. More importantly, it was done in China. We have to understand that we’re talking about a different population. We know that stroke patients in China have a higher prevalence of atherosclerotic disease and also coronary atherosclerosis. Also, they are more frequently carriers of mutations of the CYP alleles that make clopidogrel less effective. The other thing is the standard of care, which may be different from other countries.

It’s a great question, how much evidence is enough. I think we should go back in time and just see the story between CHANCE and POINT and ask ourselves, “Did we need the results of POINT to influence our clinical practice?” I think there are people who would say yes and people who would say no, but my take is that INSPIRES (Intensive Statin and Antiplatelet Therapy for Acute High-Risk Intracranial or Extracranial Atherosclerosis) provides a rationale for a practice that we have been already doing. For me, as a clinician, I think that the evidence is robust and we can extrapolate it into our patients—of course, with all these asterisks and limitations you mentioned.

James Douketis: Thank you. My last question is, let’s say you get a call from the emergency department from a hospital about a patient and they’re outside of the window for thrombolysis, maybe they’re not a good candidate for thrombectomy. What would you recommend, what do you do in terms of anticoagulant therapy? Assuming that, as you mentioned, most of them are, let’s say, within 24 hours or 36 hours after the onset of symptoms. Are there individuals in whom perhaps you would not recommend DAPT? When we’re saying that, we’re implying a loading dose of clopidogrel of ≥300 mg and then, say, aspirin in addition to that. How would you handle a call like that from the emergency department?

Aristeidis Katsanos: That’s an excellent question and you bring a very important point and something that we should highlight and mention. A lot of these trials that we discussed didn’t include patients with thrombolysis and thrombectomy, so in patients who receive acute reperfusion therapies, we have little evidence to support the use of DAPT. If a patient, as you said, is not eligible for reperfusion and they present, first I look at the time window and now with INSPIRES, I would feel OK up to 72 hours. Again, the sooner, the better—time is brain.

Second, I do take a look at their neurologic deficits. I want to make sure that the NIHSS score is ≤5. [Third], I question myself about the mechanism. If it is cardioembolic, I feel less compelled in DAPT. If it is atherosclerotic, that provides more reassurance to me to suggest it. The other thing that wasn’t done in the trials, but I do it in my clinical practice: I’d like to take a look at the imaging, right? I’d like to open up the computed tomography (CT) scan, first of all make sure that the impact is not huge. Sometimes we have a discrepancy between the images that we see and how the patients are doing. I’ll also give you an example like posterior circulation strokes in the posterior cerebral artery. Patients can present with isolated hemianopsia, very mild deficits, and you can see a huge infarct. Sometimes you can also see hemorrhagic transformation in this infarct. If I do see a very big infarct and especially if it has hemorrhagic transformation, I’m very reserved and I probably recommend aspirin.

Of course, that comes also to the general picture. I also assess the bleeding risk of an individual, right? If somebody is very fragile, if they had a recent bleed or if there is something really, really concerning, I just weigh the expected benefits to the expected risks of the individual.

James Douketis: One last question I just thought of: how long would you keep them on DAPT if you initiate that treatment?

Aristeidis Katsanos: That’s an excellent question. Trials use different time frames going from 21 to 90 days. Post-hoc analysis suggests that the benefit is front loaded. It seems that you get most of the benefit in the first couple of weeks. Then, the benefit for the prevention of ischemia starts to wash away and the risk of bleeding starts to creep up. What I do is I stick to the 21 days, but if I feel that there is a very high-risk individual, I try to keep them at least a couple of weeks on DAPT before I drop to monotherapy.

James Douketis: Dr Katsanos, thank you so much for your insights. I think the last 15 or 20 years have witnessed tremendous advances in stroke care. This is one piece of that puzzle. We wish you and other colleagues who are working in this area the best because the advances have just been tremendous. Thank you for your continued work and also thank you for contributing to today’s discussion.

Aristeidis Katsanos: Thank you so much, Dr Douketis. It was a pleasure. Thanks again for inviting me to today’s discussion.

James Douketis: Thank you.

English

English

Español

Español

українська

українська