Siglas y abreviaturas: ACV — accidente cerebrovascular, anti-TPO — (anticuerpos) antitiroperoxidasa, ARN — ácido ribonucleico, ATA — American Thyroid Association, CTLA-4 (T lymphocyte-associated 4) — antígeno 4 asociado al linfocito T citotóxico, CV — cardiovascular, ECV — enfermedad cardiovascular, FT3 (free triiodothyronine) — triyodotironina libre, FT4 (free thyroxine) — tiroxina libre, HLA (human leukocyte antygen) — antígeno leucocitario humano, L-T4 — levotiroxina, PTPN22 (protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 22) — gen de la proteína tirosina fosfatasa no receptora de tipo 22, SPA — síndrome poliglandular autoinmune, T3 — triyodotironina, T4 — tiroxina, TPO — tiroperoxidasa, TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) — tirotropina, Tg — tiroglobulina

Resumen

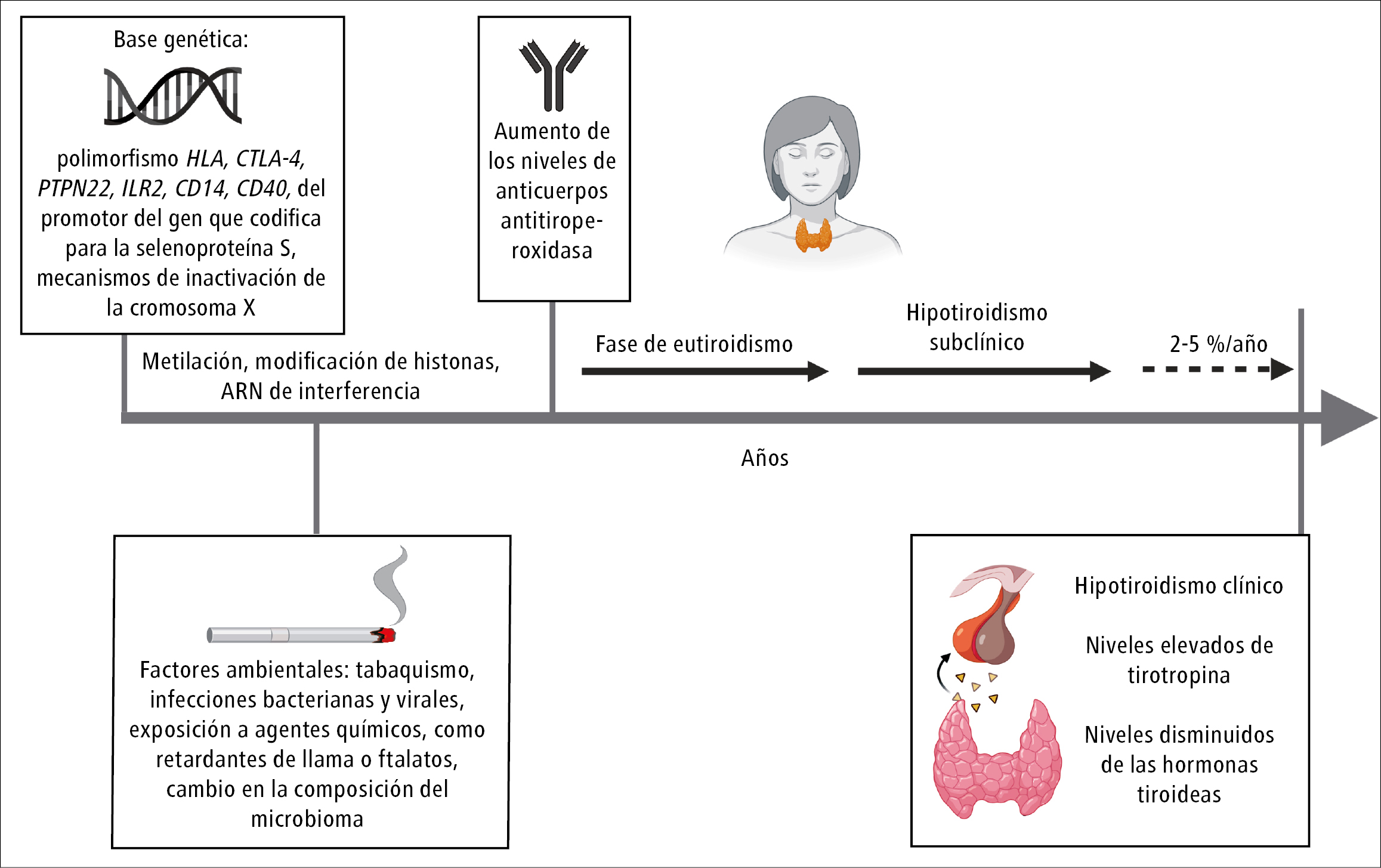

La tiroiditis crónica autoinmune (enfermedad de Hashimoto) es una enfermedad autoinmune común (en mujeres es 7-10 más frecuente que en hombres), que se desarrolla debido a la susceptibilidad genética, el efecto de factores ambientales y la composición de microbioma que modulan el mecanismo de inactivación del cromosoma X, lo que conduce a la alteración de los mecanismos de la autotolerancia. Como efecto, se produce la infiltración linfocitaria del parénquima de la glándula tiroides, intensificada por la respuesta autoinmune dependiente de anticuerpos antitiroperoxidasa (anti-TPO), lo que resulta en el daño de los tirocitos. La presencia de anticuerpos anti-TPO se asocia al riesgo 2-4 más alto de abortos espontáneos recurrentes y parto prematuro en embarazadas. La evolución clínica incluye:

1) tirotoxicosis (hashitoxicosis), que se produce a consecuencia de la destrucción de los folículos tiroideos y la liberación al torrente sanguíneo de las hormonas almacenadas

2) eutiroidismo, cuando el tejido tiroideo preservado compensa el dano de los tirocitos

3) hipotiroidismo, cuando la producción de las hormonas tiroideas por la glándula dañada resulta insuficiente.

En la fase de hashitoxicosis el tratamiento es sobre todo sintomático, normalmente con β-bloqueantes. En la fase de eutiroidismo se determinan periódicamente los niveles de tirotropina (TSH) y, basándose en los resultados, se valora la eventual progresión al hipotiroidismo. En enfermos con hipotiroidismo se emplea el tratamiento de reemplazo hormonal, pero la dosis de levotiroxina (L-T4) se ajusta según el grado de preservación de la función tiroidea y la masa corporal magra (normalmente 1,4-1,8 µg/kg/d). No hay datos suficientes a favor o en contra del uso de triyodotironina (liotironina, L-T3), excepto en embarazadas, en cuyo caso debido a la penetración insuficiente de la T3 a través de la barrera hematoencefálica solamente está indicado el uso de L-T4. En pacientes con la enfermedad de Hashimoto el riesgo de carcinoma papilar tiroideo es 1,6 veces más alto y de linfoma tiroideo es 60 veces más alto que en la población general.

Enfermedad de Hashimoto: definición y epidemiología

El nombre de la "enfermedad de Hashimoto" viene del apellido de Hakaru Hashimoto, quien en 1912 la describió por primera vez, utilizando el término "bocio linfomatoso" (struma lymphomatosa) para describir la glándula tiroides aumentada de tamaño con infiltrados linfocitarios.1 La prevalencia de la enfermedad de Hashimoto se estima en 0,3-1,5/1000, pero las mujeres enferman mucho más frecuentemente que los hombres (7-10:1).2,3 También es relevante el origen étnico: la incidencia entre las personas de raza blanca es mayor que en personas de raza negra y en asiáticos, y los habitantes de las islas del Pacífico enferman raramente.4 La prevalencia aumenta con la edad,3 especialmente en aquellas personas que tienen otras enfermedades autoinmunes diagnosticadas, p. ej. miastenia,5 esclerosis sistémica6 u otras conectivopatías,7 síndrome de Sjögren,8,9 anemia perniciosa,8,9 hepatopatía autoinmune o enfermedad celíaca.7-9 Esta poliautoinmunidad se expresa probablemente debido a las alteraciones de la respuesta inmune, al funcionamiento de las hormonas y a los factores genéticos y ambientales.10 Más raramente la enfermedad se acompaña de otras endocrinopatías de origen autoinmune, formando parte de los síndromes poliglandulares autoinmunes (SPA): tipo 1 (enfermedad de Hashimoto, enfermedad de Addison, hipoparatiroidismo, candidiasis mucocutánea crónica), tipo 2 (enfermedad de Hashimoto, enfermedad de Addison, diabetes mellitus tipo 1), o IPEX (enfermedad de Hashimoto, diabetes neonatal de tipo 1, enteropatía autoinmune, lesiones cutáneas de tipo eccematoso).9,11 Los SPA tienen un determinado origen genético, p. ej.: las mutaciones en el gen AIRE en el SPA de tipo 1, o las variantes patogénicas del gen FOXP3 en el síndrome IPEX.9,11

Patogenia

Las manifestaciones autoinmunes de la enfermedad de Hashimoto son la consecuencia de la acción de los factores ambientales y genéticos, como polimorfismos de los antígenos leucocitarios humanos (HLA), del antígeno 4 asociado a los linfocitos T citotóxicos (CTLA-4) o del gen de la proteína tirosina fosfatasa no receptora de tipo 22 (PTPN22), así como de los mecanismos de inactivación del cromosoma X, debido a los cuales se produce una alteración del equilibrio entre los mecanismos de autotolerancia, mantenida y regulada por los linfocitos T y B.9,12-14 Además, la autoinmunización de la tiroides se asocia con polimorfismos genéticos de los autoantígenos, las citoquinas y sus receptores (p. ej. del receptor de la interleucina 2 [IL2R]), los receptores estrogénicos, las moléculas de adhesión (CD14, CD40), el promotor del gen que codifica para la selenoproteína S y los productos de los genes asociados a la apoptosis.9,15,16-18 Esta susceptibilidad genética está sujeta a la modificación epigenética por metilación, modificación de histonas e interferencia por ARN no codificante (fig. 1).En las personas con predisposición genética, las enfermedades autoinmunes pueden ser desencadenadas por determinados factores ambientales, como infecciones bacterianas y virales, tabaquismo, microquimerismo fetal o exposición a ciertos agentes químicos, como atenuantes de la inflamabilidad o ftalatos.20,21 Simultáneamente, una exposición limitada a los factores ambientales, p. ej. habitar en condiciones casi estériles, también se asocia con una alta prevalencia de las enfermedades alérgicas y autoinmunes, incluida la enfermedad de Hashimoto.22 También se señala una relación entre la composición de microbioma y la presencia de tiroiditis autoinmune: los datos indican que en personas con enfermedad de Hashimoto las Bifidobacterium y Lactobacillus son mucho más escasas, mientras que la microflora nociva (p. ej. Bacteroides fragilis) es mucho más numerosa que en la población de control que no presenta autoinmunización.23 La dieta también puede influir en la historia natural de la enfermedad. Se indica una relación entre el consumo excesivo de yodo y una mayor (incluso 4 veces) prevalencia de la enfermedad de Hashimoto.24 En las personas con predisposición genética, el yodo aumenta la inmunogenicidad de la tiroglobulina (Tg), lo que puede explicar tal relación.25 Las personas con enfermedad de Hashimoto no deben suplementar excesivamente el yodo, pero se recomienda que las embarazadas y las mujeres lactantes suplementen este elemento hasta llegar a la ingesta total de 250 µg/d.26 Según algunos datos, la enfermedad de Hashimoto puede activarse por el consumo reducido de selenio, pero la suplementación de este elemento en los ensayos clínicos no cambió el transcurso de esta enfermedad a pesar de haber observado una disminución en los niveles de anti-TPO en suero.27,28 Debido a la asociación con la enfermedad celíaca, se sugiere que una dieta pobre en gluten puede modificar el curso de la enfermedad de Hashimoto. En un estudio prospectivo realizado en pacientes con enfermedad celíaca, en comparación con el grupo de control compuesto por personas que no padecían esta enfermedad, se observó una relación entre el uso de la dieta pobre en gluten y la disminución del volumen tiroideo, a pesar de haber mantenido los niveles de anticuerpos anti-TPO.29 En otro ensayo realizado en personas que seguían una dieta pobre en gluten, en las cuales se observó la presencia de anticuerpos anti-TPO y antitransglutaminasa, se constató una disminución de los niveles de anticuerpos anti-TPO en comparación con las personas seropositivas que seguían una dieta con gluten.30 Se desconoce la importancia de la disminución de los niveles de anticuerpos anti-TPO en suero para el curso de la enfermedad de Hashimoto. En cuanto al mecanismo de desarrollo, la enfermedad de Hashimoto se caracteriza por un ataque directo de los linfocitos T sobre la glándula tiroides, visible en el estudio histológico en forma de infiltrados linfoplasmocitarios, fibrosis, formación de folículos linfáticos y atrofia del parénquima tiroideo.31 Sobre la base del cuadro clínico e histológico se distinguen varias formas de la enfermedad, incluida la forma fibrótica y atrófica,32 la tiroiditis de Riedel33 y la forma IgG4-dependiente.34 Zhang y cols. —utilizando la tecnología de secuenciación de ARN de células individuales— demostraron que en la patogenia de la enfermedad el microambiente tiroideo desempeña un papel importante, asociado a la participación de 3 subtipos de células estromales en la movilización de las células inflamatorias del sistema inmunitario que infiltran la glándula tiroides.35 Estas células destruyen las células foliculares y conducen al aumento de la exposición de antígenos tiroideos (TPO y Tg), lo que adicionalmente aumenta la producción de autoanticuerpos (anti-Tg y anti-TPO), conduciendo a la progresión ulterior de la destrucción folicular y, en consecuencia, al hipotiroidismo. No obstante, se debe tener en cuenta que los niveles elevados de anti-TPO y anti-Tg (15-25 %) se observan mucho más frecuentemente que las manifestaciones clínicas de la enfermedad de Hashimoto (hipotiroidismo), sobre todo en poblaciones con el consumo suficiente de yodo (donde no se presenta su déficit), así como en mujeres y personas de edad avanzada.36

Fig. 1. Enfermedad de Hashimoto: etiología e historia natural

Bibliografía:

- Hashimoto H., The knowledge of the lymphomatous changes in the thyroid gland (struma lymphomatosa) [en alemán], Archiv für klinische Chirurgie, 1912; 97: 219

- Caturegli P., De Remigis A., Chuang K. y cols., Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: celebrating the centennial through the lens of the Johns Hopkins hospital surgical pathology records, Thyroid, 2013; 23: 142-150

- Ralli M., Angeletti D., Fiore M. y cols., Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: an update on pathogenic mechanisms, diagnostic protocols, therapeutic strategies, and potential malignant transformation, Autoimmun. Rev., 2020; 19: 102 649

- McLeod D.S., Caturegli P., Cooper D.S. y cols., Variation in rates of autoimmune thyroid disease by race/ethnicity in US military personnel, JAMA, 2014; 311: 1563-1565

- Song R.H., Yao Q.M., Wang B. y cols., Thyroid disorders in patients with myasthenia gravis: a systematic review and meta analysis, Autoimmun. Rev., 2019; 18: 102 368

- Yao Q., Song Z., Wang B. y cols., Thyroid disorders in patients with sys temic sclerosis: a systematic review and meta analysis, Autoimmun. Rev., 2019; 18: 634-636

- Nakamura H., Usa T., Motomura M. y cols., Prevalence of interrelated auto antibodies in thyroid diseases and autoimmune disorders, J. Endocrinol. Ivest., 2008; 31: 861-865

- Feldt Rasmussen U., Hoier Madsen M., Bech K. y cols., Anti thyroid peroxidase antibodies in thyroid disorders and non thyroid autoimmune diseases, Autoimmunity, 1991; 9: 245-254

- Bliddal S., Nielsen C.H., Feldt Rasmussen U., Recent advances in understanding autoimmune thyroid disease: the tallest tree in the forest of polyautoimmunity, F1000Research, 2017; 6: 1776

- Lazúrová I., Benhatchi K., Autoimmune thyroid diseases and nonorgan specific autoimmunity, Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn., 2012; 122, suppl. 1: 55-59

- Eisenbarth G.S., Gottlieb P.A., Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes, N. Engl. J. Med., 2004; 350: 2068-2079

- Brix T.H., Hegedüs L., Twin studies as a model for exploring the aetiology of autoimmune thyroid disease, Clin. Endocrinol., 2012; 76: 457-464

- Gleicher N., Barad D.H., Gender as risk factor for autoimmune diseases, J. Autoimmun., 2007; 28: 1-6

- Brand O., Gough S., Heward J., HLA, CTLA 4 and PTPN22: the shared genetic master key to autoimmunity?, Expert Rev. Mol. Med., 2005; 7: 1-15

- Weetman A.P., The immunopathogenesis of chronic autoimmune thyroiditis one century after hashimoto, Eur. Thyroid J., 2013; 1: 243-250

- Johar A., Sarmiento Monroy J.C., Rojas Villarraga A. y cols., Definition of mutations in polyautoimmunity, J. Autoimmun., 2016; 72: 65-72

- Santos L.R., Duraes C., Mendes A. y cols., A polymorphism in the promoter region of the selenoprotein S gene (SEPS1) contributes to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis susceptibility, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2014; 99: E719-723

- Jia X., Wang B., Yao Q. y cols., Variations in CD14 gene are associated with autoimmune thyroid diseases in the Chinese population, Front. Endocrinol., 2018; 9: 811

- Feil R., Fraga M.F., Epigenetics and the environment: emerging patterns and implications, Nat. Rev. Genet., 2012; 13: 97-109

- Lepez T., Vandewoestyne M., Deforce D., Fetal microchimeric cells in autoimmune thyroid diseases: harmful, beneficial or innocent for the thyroid gland?, Chimerism, 2013; 4: 111-118

- Mynster Kronborg T., Frohnert Hansen J., Nielsen C.H. y cols., Effects of the commercial flame retardant mixture DE 71 on cytokine production by human immune cells, PloS One, 2016; 11: e0154621

- Wiersinga W.M., Clinical relevance of environmental factors in the pathogenesis of autoimmune thyroid disease, Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul), 2016; 31: 213-222

- Gong B., Wang C., Meng F. y cols., Association between gut microbiota and autoimmune thyroid disease: a systematic review and meta analysis, Front. Endocrinol., 2021; 12: 774362

- Aghini Lombardi F., Fiore E., Tonacchera M. y cols., The effect of voluntary iodine prophylaxis in a small rural community: the Pescopagano survey 15 years later, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2013; 98: 1031-1039

- Carayanniotis G., Recognition of thyroglobulin by T cells: the role of iodine, Thyroid, 2007; 17: 963-973

- Alexander E.K., Pearce E.N., Brent G.A. y cols., 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and the postpartum, Thyroid, 2017; 27: 315-389

- Toulis K.A., Anastasilakis A.D., Tzellos T.G. y cols., Selenium supplementation in the treatment of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: a systematic review and a meta analysis, Thyroid, 2010; 20: 1163-1173

- Winther K.H., Wichman J.E., Bonnema S.J. y cols., Insufficient documentation for clinical efficacy of selenium supplementation in chronic autoimmune thyroiditis, based on a systematic review and meta analysis, Endocrine, 2017; 55: 376-385

- Metso S., Hyytiä Ilmonen H., Kaukinen K. y cols., Gluten free diet and auto immune thyroiditis in patients with celiac disease. A prospective controlled study, Scand. J. Gastroenterol., 2012; 47: 43-48

- Krysiak R., Szkrobka W., Okopień B., The effect of gluten free diet on thyroid autoimmunity in drug naive women with hashimoto’s thyroiditis: a pilot study, Exp. Clin. Endocrinol., 2019; 127: 417-422

- Giordano C., Stassi G., De Maria R. y cols., Potential involvement of Fas and its ligand in the pathogenesis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Science, 1997; 275: 960-963

- Ahmed R., Al Shaikh S., Akhtar M., Hashimoto thyroiditis: a century later, Adv. Anat. Pathol., 2012; 19: 181-186

- Hennessey J.V., Clinical review: Riedel’s thyroiditis: a clinical review, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2011; 96: 3031-3041

- Stone J.H., Khosroshahi A., Deshpande V. y cols., Recommendations for the nomenclature of IgG4 related disease and its individual organ system manifestations, Arthritis Rheum., 2012; 64: 3061-3067

- Zhang Q.Y., Ye X.P., Zhou Z. y cols., Lymphocyte infiltration and thyrocyte destruction are driven by stromal and immune cell components in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Nat. Commun., 2022; 13: 775

- Pedersen I.B., Knudsen N., Jorgensen T. y cols., Thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin autoantibodies in a large survey of populations with mild and moderate iodine deficiency, Clin. Endocrinol., 2003; 58: 36-42

- Jonklaas J., Bianco A.C., Bauer A.J. y cols., Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the american thyroid association task force on thyroid hormone replacement, Thyroid, 2014; 24: 1670-1751

- Biondi B., Cappola A.R., Cooper D.S., Subclinical hypothyroidism: a review, JAMA, 2019; 322: 153-160

- Boucai L., Hollowell J.G., Surks M.I., An approach for development of age, gender, and ethnicity specific thyrotropin reference limits, Thyroid, 2011; 21: 5-11

- Jonklaas J., Optimal thyroid hormone replacement, Endocr. Rev, 2022; 43: 366-404

- Caturegli P., De Remigis A., Rose N.R., Hashimoto thyroiditis: clinical and diagnostic criteria, Autoimmun. Rev., 2014; 13: 391-397

- Anderson L., Middleton W.D., Teefey S.A. y cols., Hashimoto thyroiditis: part 2, sonographic analysis of benign and malignant nodules in patients with diffuse Hashimoto thyroiditis, AJR Am. J. Roentgenol., 2010; 195: 216-222

- McLachlan S.M., Rapoport B., Why measure thyroglobulin autoantibodies rather than thyroid peroxidase autoantibodies?, Thyroid, 2004; 14: 510-520

- Jonklaas J., Bianco A.C., Cappola A.R. y cols., Evidence based use of levothyroxine/liothyronine combinations in treating hypothyroidism: a consensus document, Eur. Thyroid J., 2021; 10: 10-38

- Fatourechi V., McConahey W.M., Woolner L.B., Hyperthyroidism associated with histologic Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Mayo Clin. Proc., 1971; 46: 682-689

- Rodondi N., den Elzen W.P., Bauer D.C. y cols., Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality, JAMA, 2010; 304: 1365-1374

- Chaker L., Baumgartner C., den Elzen W.P. y cols., Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of stroke events and fatal stroke: an individual participant data analysis, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2015; 100: 2181-2191

- Kabadi U.M., Jackson T., Serum thyrotropin in primary hypothyroidism. A possible predictor of optimal daily levothyroxine dose in primary hypothyroidism, Arch. Intern. Med., 1995; 155: 1046-1048

- Lillevang Johansen M., Abrahamsen B., Jorgensen H.L. y cols., Duration of over and under treatment of hypothyroidism is associated with increased cardiovascular risk, Eur. J. Endocrinol., 2019; 180: 407-416

- Huang H.K., Wang J.H., Kao S.L., Association of hypothyroidism with all cause mortality: a cohort study in an older adult population, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2018; 103: 3310-3318

- Lillevang Johansen M., Abrahamsen B., Jorgensen H.L. y cols., Over and under treatment of hypothyroidism is associated with excess mortality: a register based cohort study, Thyroid, 2018; 28: 566-574

- Thayakaran R., Adderley N.J., Sainsbury C. y cols., Thyroid replacement therapy, thyroid stimulating hormone concentrations, and long term health outcomes in patients with hypothyroidism: longitudinal study, BMJ, 2019; 366: 4892

- Okosieme O.E., Belludi G., Spittle K. y cols., Adequacy of thyroid hormone replacement in a general population, QJM – Mon. J. Assoc. Physicians, 2011; 104: 395-401

- Ettleson M.D., Bianco A.C., Zhu M. y cols., Sociodemographic disparities in the treatment of hypothyroidism: NHANES 2007–2012, J. Endocr. Soc., 2021; 5: bvab041

- Santini F., Pinchera A., Marsili A. y cols., Lean body mass is a major determinant of levothyroxine dosage in the treatment of thyroid diseases, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2005; 90: 124-127

- Pilo A., Iervasi G., Vitek F. y cols., Thyroidal and peripheral production of 3,5,3’ triiodothyronine in humans by multicompartmental analysis, Am. J. Physiol., 1990; 258: E715 726

- Devdhar M., Drooger R., Pehlivanova M. y cols., Levothyroxine replacement doses are affected by gender and weight, but not age, Thyroid, 2011; 21: 821-827

- Jonklaas J., Sex and age differences in levothyroxine dosage requirement, Endocr. Pract., 2010; 16: 71-79

- Hollowell J.G., Staehling N.W., Flanders W.D. y cols., Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2002; 87: 489-499

- Taylor P.N., Razvi S., Pearce S.H. y cols., Clinical review: a review of the clinical consequences of variation in thyroid function within the reference range, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2013; 98: 3562-3571

- Samuels M.H., Kolobova I., Niederhausen M. y cols., Effects of altering levothyroxine (LT4) doses on quality of life, mood, and cognition in LT4 treated subjects, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2018; 103: 1997-2008

- Samuels M.H., Kolobova I., Niederhausen M. y cols., Effects of altering levothyroxine dose on energy expenditure and body composition in subjects treated with LT4, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2018; 103: 4163-4175

- Walsh J.P., Ward L.C., Burke V. y cols., Small changes in thyroxine dosage do not produce measurable changes in hypothyroid symptoms, well being, or quality of life: results of a double blind, randomized clinical trial, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2006; 91: 2624-2630

- Boeving A., Paz Filho G., Radominski R.B. y cols., Low normal or high normal thyrotropin target levels during treatment of hypothyroidism: a prospective, comparative study, Thyroid, 2011; 21: 355-360

- Sturgess I., Thomas S.H., Pennell D.J. y cols., Diurnal variation in TSH and free thyroid hormones in patients on thyroxine replacement, Acta Endocrinol., 1989; 121: 674-676

- Massolt E.T., Meima M.E., Swagemakers S.M.A. y cols., Thyroid state regulates gene expression in human whole blood, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2018; 103: 169-178

- Nygaard B., Jensen E.W., Kvetny J. y cols., Effect of combination therapy with thyroxine (T4) and 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine versus T4 monotherapy in patients with hypothyroidism, a double-blind, randomised cross-over study, Eur. J. Endocrinol., 2009; 161: 895-902

- Bunevicius R., Kazanavicius G., Zalinkevicius R. y cols., Effects of thyroxine as compared with thyroxine plus triiodothyronine in patients with hypothyroidism, N. Eng. J. Med., 1999; 340: 424-429

- Escobar Morreale H.F., Botella Carretero J.I., Gomez Bueno M. y cols., Thyroid hormone replacement therapy in primary hypothyroidism: a randomized trial comparing L thyroxine plus liothyronine with L thyroxine alone, Ann. Intern. Med., 2005; 142: 412-424

- Saravanan P., Simmons D.J., Greenwood R. y cols., Partial substitution of thyroxine (T4) with triiodothyronine in patients on T4 replacement therapy: results of a large community based randomized controlled trial, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2005; 90: 805-812

- Valizadeh M., Seyyed Majidi M.R., Hajibeigloo H. y cols., Efficacy of combined levothyroxine and liothyronine as compared with levothyroxine monotherapy in primary hypothyroidism: a randomized controlled trial, Endocr. Res., 2009; 34: 80-89

- Ma C., Xie J., Huang X. y cols., Thyroxine alone or thyroxine plus triiodothyronine replacement therapy for hypothyroidism, Nucl. Med. Commun., 2009; 30: 586-593

- Escobar Morreale H.F., Botella Carretero J.I., Morreale de Escobar G.: Treatment of hypothyroidism with levothyroxine or a combination of levo thyroxine plus L triiodothyronine, Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2015; 29: 57-75

- Joffe R.T., Brimacombe M., Levitt A.J. y cols., Treatment of clinical hypothyroidism with thyroxine and triiodothyronine: a literature review and meta analysis, Psychosomatics, 2007; 48: 379-384

- Grozinsky Glasberg S., Fraser A., Nahshoni E. y cols., Thyroxine triiodothyronine combination therapy versus thyroxine monotherapy for clinical hypothyroidism: meta analysis of randomized controlled trials, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2006; 91: 2592-2599

- Celi F.S., Zemskova M., Linderman J.D. y cols., The pharmacodynamic equivalence of levothyroxine and liothyronine: a randomized, double blind, cross over study in thyroidectomized patients, Clin. Endocrinol., 2010; 72: 709-715

- Shakir M.K.M., Brooks D.I., McAninch E.A. y cols., Comparative effectiveness of levothyroxine, desiccated thyroid extract, and levothyroxine + liothyronine in hypothyroidism, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2021; 106: e4400-e4413

- Castagna M.G., Dentice M., Cantara S. y cols., DIO2 Thr92Ala reduces deiodinase 2 activity and serum T3 levels in thyroid deficient patients, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2017; 102: 1623-1630

- Panicker V., Saravanan P., Vaidya B. y cols., Common variation in the DIO2 gene predicts baseline psychological well being and response to combination thyroxine plus triiodothyronine therapy in hypothyroid patients, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2009; 94: 1623-1629

- Carle A., Faber J., Steffensen R. y cols., Hypothyroid patients encoding combined MCT10 and DIO2 gene polymorphisms may prefer L T3 + L T4 combination treatment – data using a blind, randomized, clinical study, Eur. Thyroid J., 2017; 6: 143-151

- Wouters H.J., van Loon H.C., van der Klauw M.M. y cols., No effect of the Thr92Ala polymorphism of deiodinase 2 on thyroid hormone parameters, health related quality of life, and cognitive functioning in a large population based cohort study. Thyroid, 2017; 27: 147–155

- Young Cho Y., Jeong Kim H., Won Jang H. y cols., The relationship of 19 functional polymorphisms in iodothyronine deiodinase and psychological well being in hypothyroid patients, Endocrine, 2017; 57: 115-124

- Appelhof B.C., Fliers E., Wekking E.M. y cols., Combined therapy with levothyroxine and liothyronine in two ratios, compared with levothyroxine monotherapy in primary hypothyroidism: a double blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2005; 90: 2666-2674

- Gan T., Randle R.W.: The role of surgery in autoimmune conditions of the thyroid, Surg. Clin. North Am., 2019; 99: 633-648

- Guldvog I., Reitsma L.C., Johnsen L. y cols., Thyroidectomy versus medical management for euthyroid patients with hashimoto disease and persisting symptoms: a randomized trial, Ann. Intern. Med., 2019; 170: 453-464

- Jankovic B., Le K.T., Hershman J.M.: Clinical Review: Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and papillary thyroid carcinoma: is there a correlation?, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2013; 98: 474-482

- Sulaieva O., Selezniov O., Shapochka D. y cols., Hashimoto’s thyroiditis attenuates progression of papillary thyroid carcinoma: deciphering immunological links, Heliyon, 2020; 6: e03 077

- Abbasgholizadeh P., Naseri A., Nasiri E. y cols., Is Hashimoto thyroiditis associated with increasing risk of thyroid malignancies? A systematic review and meta analysis, Thyroid Res., 2021; 14: 26

- Haugen B.R., Alexander E.K., Bible K.C. y cols., 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer, Thyroid, 2

- De Leo S., Pearce E.N.: Autoimmune thyroid disease during pregnancy, Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol., 2018; 6: 575-586

- Thangaratinam S., Tan A., Knox E. y cols., Association between thyroid autoantibodies and miscarriage and preterm birth: meta-analysis of evidence, BMJ, 2011; 342: d2616

- Xie J., Jiang L., Sadhukhan A. y cols., Effect of antithyroid antibodies on women with recurrent miscarriage: a metaanalysis, Am. J. Reprod. Immunol, 2020; 83: e13 238

- Liu H., Shan Z., Li C. y cols., Maternal subclinical hypothyroidism, thyroid autoimmunity, and the risk of miscarriage: a prospective cohort study, Thyroid, 2014; 24: 1642-1649

- Korevaar T.I.M., Derakhshan A., Taylor P.N. y cols., Association of thyroid function test abnormalities and thyroid autoimmunity with preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis, JAMA, 2019; 322: 632-641

- Lee S.Y., Pearce E.N., Assessment and treatment of thyroid disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period, Nat. Rev. Endocrinol., 2022; 18: 158-171

- Korevaar T.I., Schalekamp Timmermans S., de Rijke Y.B. y cols., Hypothyroxinemia and TPO antibody positivity are risk factors for premature delivery: the generation R study, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2013; 98: 4382-4390

- Thompson W., Russell G., Baragwanath G. y cols., Maternal thyroid hormone insufficiency during pregnancy and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring: a systematic review and meta analysis, Clin. Endocrinol., 2018; 88: 575-584

- Davis L.E., Leveno K.J., Cunningham F.G.: Hypothyroidism complicating pregnancy, Obstet. Gynecol., 1988; 72: 108-112

- Leung A.S., Millar L.K., Koonings P.P. y cols., Perinatal outcome in hypothyroid pregnancies, Obstet. Gynecol., 1993; 81: 349-353

- Mannisto T., Mendola P., Grewal J. y cols., Thyroid diseases and adverse pregnancy outcomes in a contemporary US cohort, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 2013; 98: 2725-2733

- Okosieme O.E., Khan I., Taylor P.N.: Preconception management of thyroid dysfunction, Clin. Endocrinol., 2018; 89: 269-279

- Calvo R., Obregon M.J., Ruiz de Ona C. y cols., Congenital hypothyroidism, as studied in rats. Crucial role of maternal thyroxine but not of 3,5,3’ tri iodothyronine in the protection of the fetal brain, J. Clin. Invest., 1990; 86: 889-899

- Lau L., Benham J.L., Lemieux P. y cols., Impact of levothyroxine in women with positive thyroid antibodies on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta analysis of randomised controlled trials, BMJ Open, 2021; 11: e043 751

- Ma R., Morshed S.A., Latif R. y cols., Thyroid cell differentiation from murine induced pluripotent stem cells, Front. Endocrinol., 2015; 6: 56

- Antonica F., Kasprzyk D.F., Opitz R. y cols., Generation of functional thyroid from embryonic stem cells, Nature, 2012; 491: 66-71

Español

Español

English

English

українська

українська