Peng QY, Wang XT, Zhang LN; Chinese Critical Care Ultrasound Study Group (CCUSG). Findings of lung ultrasonography of novel corona virus pneumonia during the 2019-2020 epidemic. Intensive Care Med. 2020 May;46(5):849-850. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05996-6. Epub 2020 Mar 12. PubMed PMID: 32166346; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7080149.

Johri AM, Galen B, Kirkpatrick JN, Lanspa M, Mulvagh S, Thamman R. ASE Statement on Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) During the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Pandemic. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2020 Apr 15. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2020.04.017. Epub ahead of print. PMCID: PMC7158805.

Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020 Apr 10. pii: S0049-3848(20)30120-1. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 32291094; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7146714.

Huang Yi, Wang S, Liu Y, et al. A Preliminary Study on the Ultrasonic Manifestations of Peripulmonary Lesions of Non-Critical Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (COVID-19) (February 26, 2020). Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3544750.

Lee JH, Lee SH, Yun SJ. Comparison of 2-point and 3-point point-of-care ultrasound techniques for deep vein thrombosis at the emergency department: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 May;98(22):e15791. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015791. PubMed PMID: 31145304; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6709014.

Pagano A, Numis FG, Visone G, et al. Lung ultrasound for diagnosis of pneumonia in emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. 2015 Oct;10(7):851-4. doi: 10.1007/s11739-015-1297-2. Epub 2015 Sep 7. PubMed PMID: 26345533.

Zanobetti M, Poggioni C, Pini R. Can chest ultrasonography replace standard chest radiography for evaluation of acute dyspnea in the ED? Chest. 2011 May;139(5):1140-1147. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0435. Epub 2010 Oct 14. PubMed PMID: 20947649.

This chapter is meant to summarize the currently known lung ultrasound findings seen in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). It requires prior knowledge of lung ultrasonography. For further information on lung ultrasonography acquisition and interpretation, you may refer to Western Sono (westernsono.ca) from Western University.

IntroductionTop

Point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) is a relatively new technology that has evolved considerably over the last decade. The advantages of POCUS, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, include ease of use, bedside availability, prevention of transfer and potentially also of virus transmission, less burdensome disinfection, and lower staff and personal protective equipment (PPE) requirements. A multiorgan bedside ultrasound assessment can define the extent of the disease and may suggest an alternative diagnosis for the clinical presentation.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest remains the best available modality for the assessment of lung parenchymal involvement in patients with COVID-19 (see COVID-19: Computed Tomography). As lung changes in these patients tend to be distributed along the pleura, lung ultrasonography has high sensitivity and the findings are correlated with peripheral findings of thoracic CT.

It is worth noting that all imaging modalities used in patients with COVID-19, including chest radiography, lung ultrasonography, and CT of the chest, lack specificity. The findings described in this chapter may be due to a number of other etiologies, including other infectious causes, such as different viral infections (eg, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus) and other forms of atypical pneumonia, or inflammatory conditions. Viral testing performed in patients with clinical suspicion of COVID-19 remains the only specific method of diagnosis and the absence of findings on imaging studies does not exclude the disease. Imaging modalities provide additional information that can be integrated into the clinical context.

Lung UltrasonographyTop

Videos mentioned in the text can be found at the end of the chapter.

Lung ultrasound findings in patients with COVID-19 include:

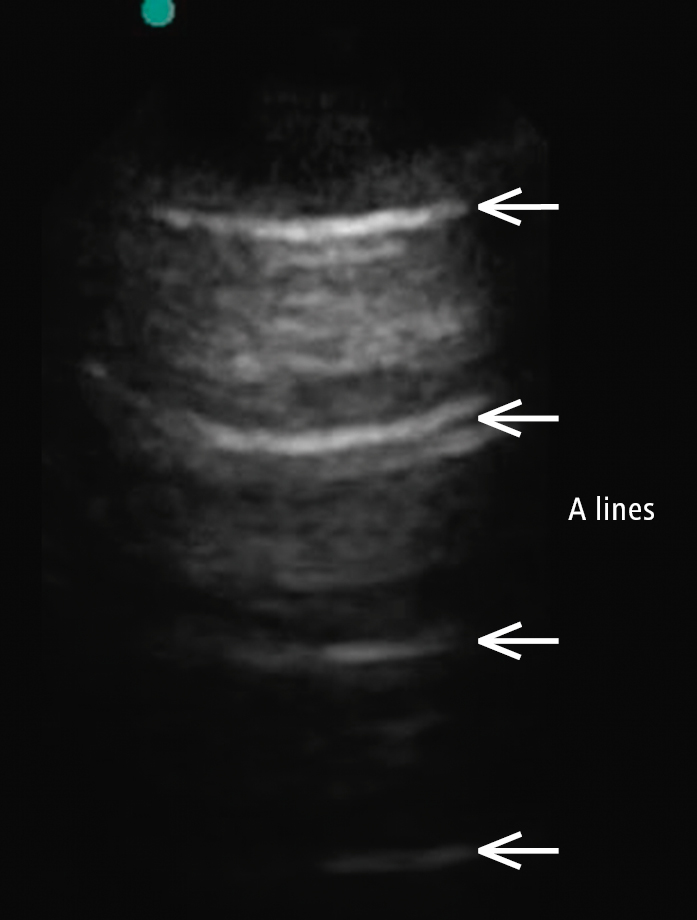

1) A line (Video 1, Figure 20.1-1).

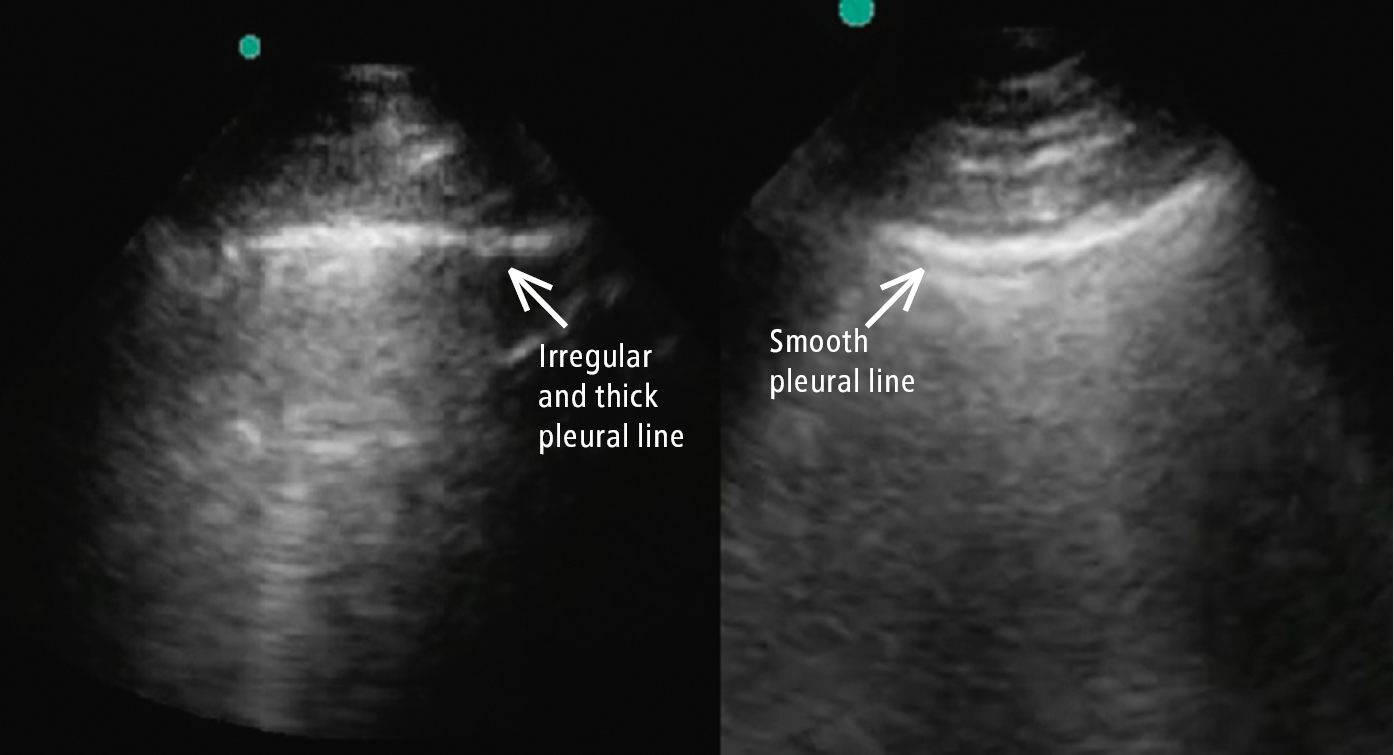

2) Thickening of the pleural line with pleural line irregularity (Video 2, Figure 20.1-2).

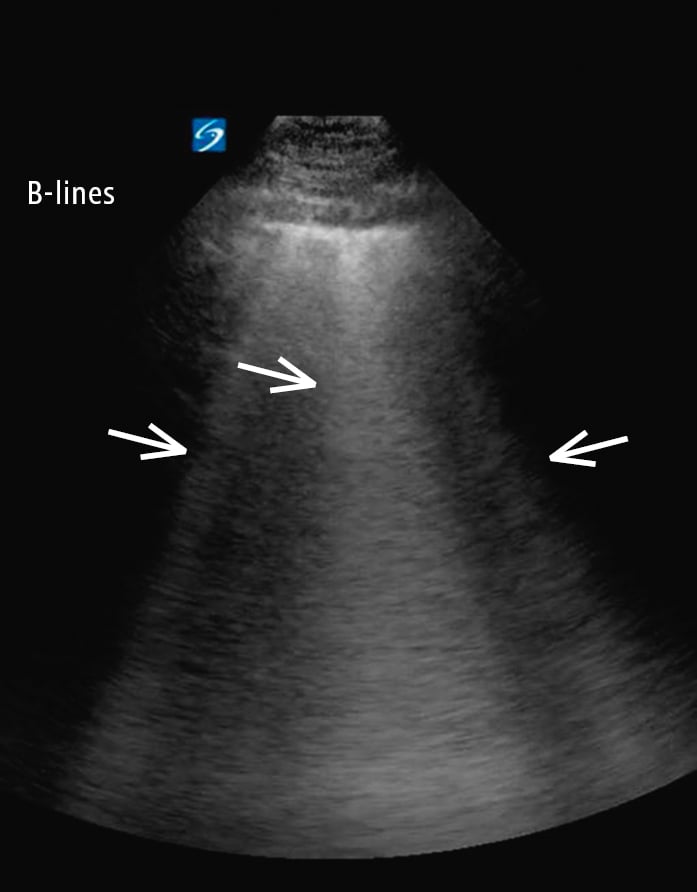

3) B lines in a variety of patterns, including focal (patchy), multifocal, and confluent (Video 3, Figure 20.1-3).

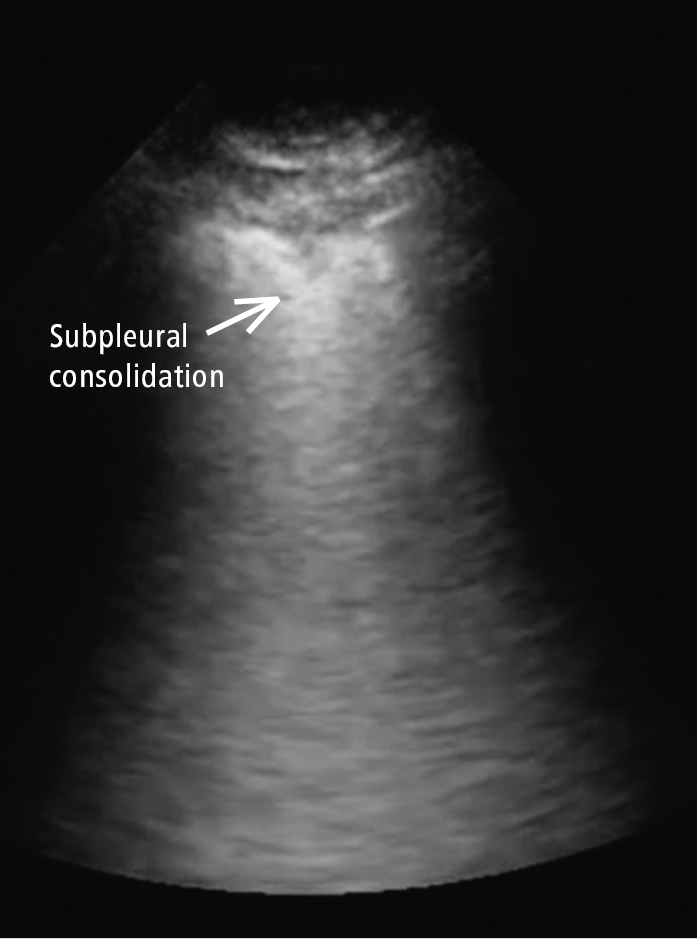

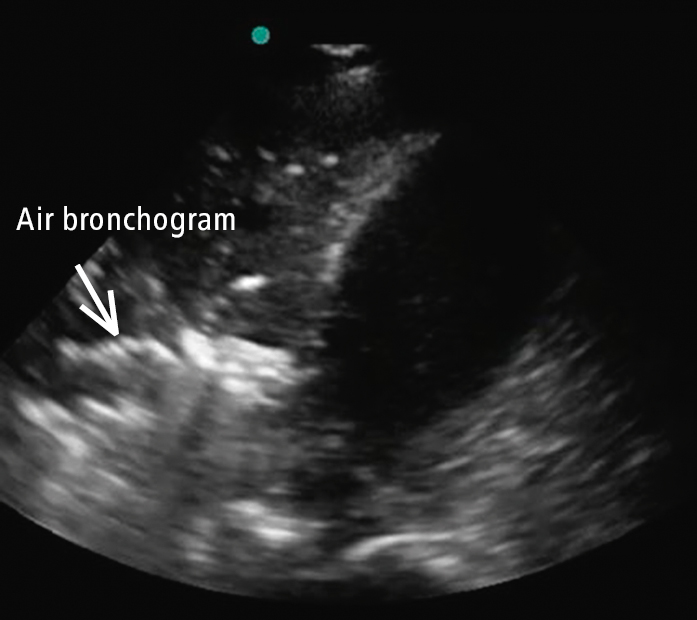

4) Consolidations, including nontranslobar (Video 4, Figure 20.1-4), translobar, and dynamic air bronchogram (Video 5, Figure 20.1-5).

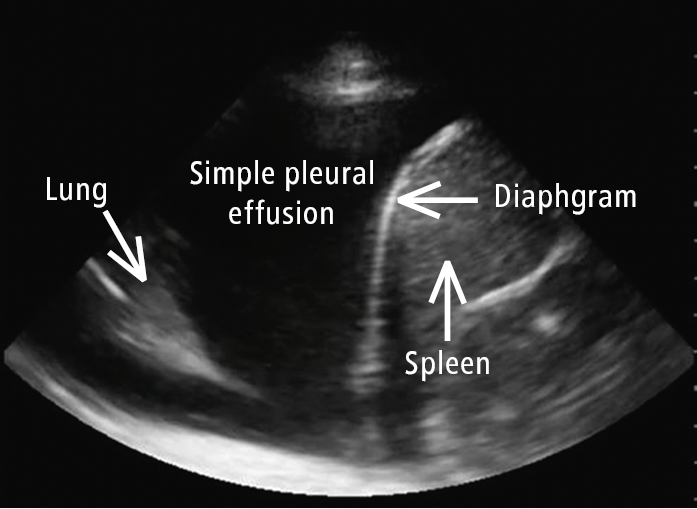

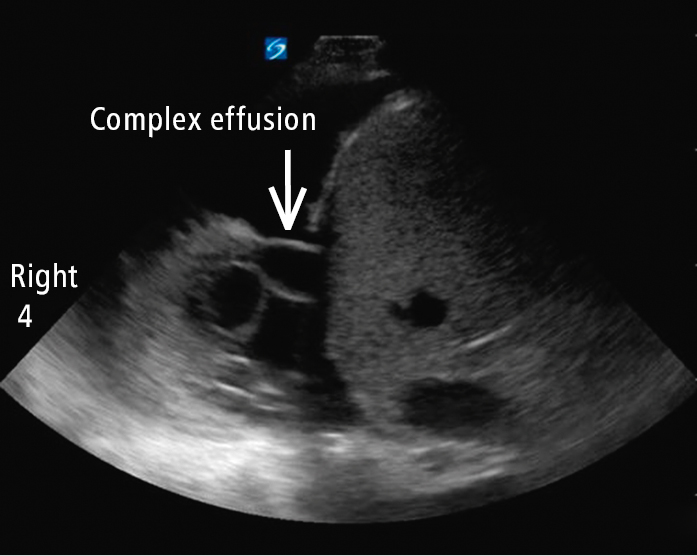

5) Pleural effusions are uncommon (Video 6, Figure 20.1-6, Video 7, Figure 20.1-7).

Lung ultrasound findings described in different stages of COVID-19:

1) Early or mild disease: Focal patchy B lines.

2) Progressive disease: Alveolar interstitial syndrome (multifocal or confluent B lines; Video 3, Figure 20.1-3).

3) Convalescence or recovery phase and very early presentation: A lines (Figure 20.1-1).

Assessment of Alternative Diagnoses

Lung ultrasonography can be used in the assessment of alternative diagnoses of different clinical presentations during the COVID-19 pandemic. The presence of symmetric B lines with a smooth pleural line suggests cardiogenic pulmonary edema as the cause of shortness of breath (Video 8).

Pleural effusions are rare. The presence of a large and especially complex-looking effusion would suggest an alternative diagnosis (Video 7), preexisting condition, or a complication, such as secondary bacterial infection with parapneumonic effusion.

Point-of-Care EchocardiographyTop

Echocardiographic assessment plays an important role in patients with COVID-19, especially in the critically ill, as echocardiographic findings may correlate with the severity of the disease. In 2020, the American Society of Echocardiography issued a statement with recommendations for POCUS during the pandemic.

Indications for cardiac POCUS in patients with COVID-19:

1) Detection or characterization of preexisting cardiovascular disease.

2) Monitoring: Using POCUS it may be possible to assess changes in cardiac function over time through quick routine examinations.

3) Elucidation of cardiovascular abnormalities potentially associated with COVID-19:

a) Pericardial effusion and myocarditis may progress to shock.

b) Right ventricular abnormalities and acute pulmonary hypertension may be suggestive of thromboembolic disease.

c) Left ventricular systolic dysfunction, either global or regional, may be associated with myocarditis, a stress-induced cardiomyopathy pattern, or epicardial or microvascular coronary thrombosis.

Vascular ULTRASONOGRAPHYTop

Vascular POCUS includes procedural guidance (eg, central venous catheter placement) and inferior vena cava assessment, which may be helpful for hemodynamic assessment in conjunction with cardiac POCUS.

The risk of venous thrombosis increases with any critically ill patient and is even more significant in the prothrombotic state in individuals with COVID-19. The 2-point compression POCUS technique may be of use.

Risk of Disease TransmissionTop

Despite its advantages, ultrasonography can be a source of harm if infection control protocols are not followed. An example can be found at the website of the Canadian Point of Care Ultrasound Society (cpocus.ca), which published a protocol for protection and disinfection of both handheld and cart-based ultrasound systems during the COVID-19 outbreak.

FiguresTop

Figure 20.1-1. A-line pattern, which suggests normal aeriation of the lung and corresponds to a normal chest radiograph. A line is a repetitive reverberation artifact of the pleura.

Figure 20.1-2. Comparison between a smooth pleural line (cardiogenic pulmonary edema; right arrow) and a thick irregular pleural line (COVID-19; left arrow). Of note, there are B lines in both images.

Figure 20.1-3. Multiple B lines (arrows) with confluent B lines (middle arrow). B lines are well-defined, vertical, hyperechoic, dynamic artifacts originating from the pleural line and extending to the bottom of the screen. Patchy or focal B lines is a description based on examination of 8 to 12 lung points.

Figure 20.1-4. Nontranslobar consolidation (subpleural consolidation; arrow) in COVID-19, in addition to the thick irregular pleural line with discontinuity.

Figure 20.1-5. Translobar consolidation of the right lower lobe with hepatization of the lung, in addition to the finding of dynamic air bronchogram (refer to Video 4, which demonstrates dynamic air bronchogram in the area of the arrow).

Figure 20.1-6. Right-sided large simple pleural effusion with anatomy marked by arrows. An uncommon presentation in COVID-19, which raises the question about an alternative explanation of hypoxia.

Figure 20.1-7. Right-sided pleural effusion with multiple thick fibrin strands suggestive of complexity. This is not a finding consistent with COVID-19. It is suggestive of an alternative diagnosis or a secondary bacterial infection with parapneumonic effusion.

VideosTop

Video 1

Video 1. A-line pattern, which suggests normal aeriation of the lung and corresponds to a normal chest radiograph. A line is a repetitive reverberation artifact of the pleura.

Video 2

Video 2. Thickening of the pleural line with pleural line irregularity.

Video 3

Video 3. Multiple B lines with confluent B lines. B lines are well-defined, vertical, hyperechoic, dynamic artifacts originating from the pleural line and extending to the bottom of the screen.

Video 4

Video 4. Nontranslobar consolidation (subpleural consolidation) in COVID-19, in addition to the thick irregular pleural line with discontinuity.

Video 5

Video 5. Translobar consolidation of the right lower lobe with hepatization of the lung, in addition to the finding of dynamic air bronchogram.

Video 6

Video 6. Right-sided large simple pleural effusion. An uncommon presentation in COVID-19, which raises the question about an alternative explanation of hypoxia.

Video 7

Video 7. Right-sided pleural effusion with multiple thick fibrin strands suggestive of complexity. This is not a finding consistent with COVID-19. It is suggestive of an alternative diagnosis or a secondary bacterial infection with parapneumonic effusion.

Video 8

Video 8. COVID-19 vs cardiogenic pulmonary edema.