MacDonald SH, Travers J, She NE, et al. Primary care interventions to address physical frailty among community-dwelling adults aged 60 years or older: a meta-analysis. PloS One, 2020;15(2): e0228821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228821. eCollection 2020. PMID: 32032375; PMCID: PMC7006935.

Dent E, Morley JE, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, et al. Physical frailty: ICFSR international clinical practice guidelines for identification and management. J Nutr Health Aging, 2019;23(9):771-787. doi: 10.1007/s12603-019-1273-z. PMID: 31641726; PMCID: PMC6800406.

Negm AM, Kennedy CC, Thabane L, et al. Management of frailty: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMDA, 2019;20:1190-1198. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.009. PMID: 31564464.

Dent E, Morley JE, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for sarcopenia (CFSR): screening, diagnosis and management. J Nutr Health Aging, 2018;22(10):1148-1161. doi: 10.1007/s12603-018-1139-9. PMID: 30498820.

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752-762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. Epub 2013 Feb 8. PMID: 23395245; PMCID: PMC4098658.

Definition, Etiology, pathogenesisTop

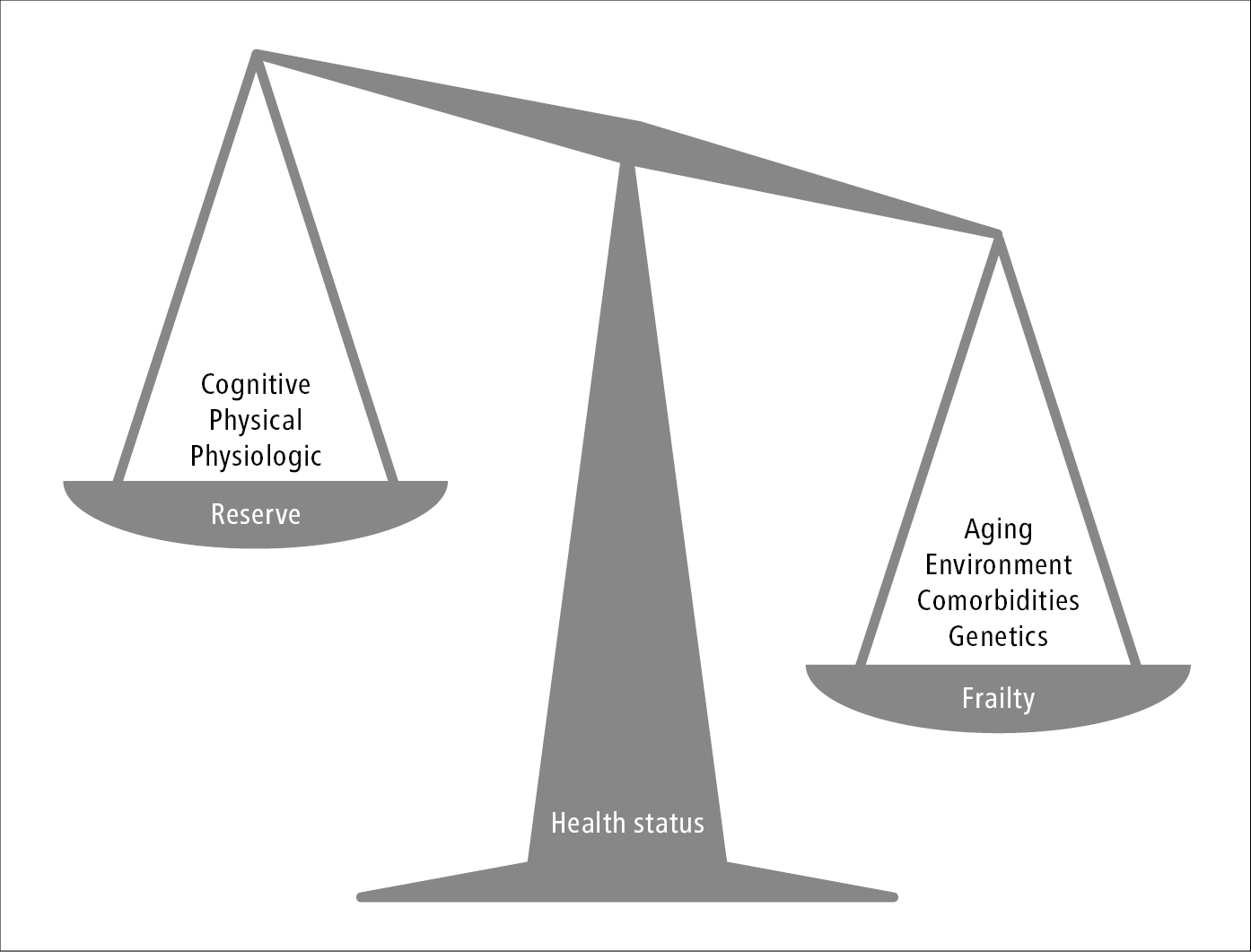

Frailty is a dynamic state of decreased physiologic, functional, or cognitive reserve resulting in increased vulnerability to acute health stressors. The relation between frailty and reserve can be conceptualized as a set of scales (Figure 8.2-1). If aging, environmental factors, comorbidities, and genetics outweigh an individual’s cognitive, physical, or physiologic reserve, it may only take a minor illness such as a urinary tract infection or change in medications to cause a large change in functional status.

The prevalence of frailty varies depending on the population. Frailty in the community ranges from 12% to 24% in those aged >65 years. Almost 50% of community-dwelling seniors are prefrail, and rates tend to be higher in women than in men. In long-term care, the prevalence can reach 75%, depending on the assessment tool used.

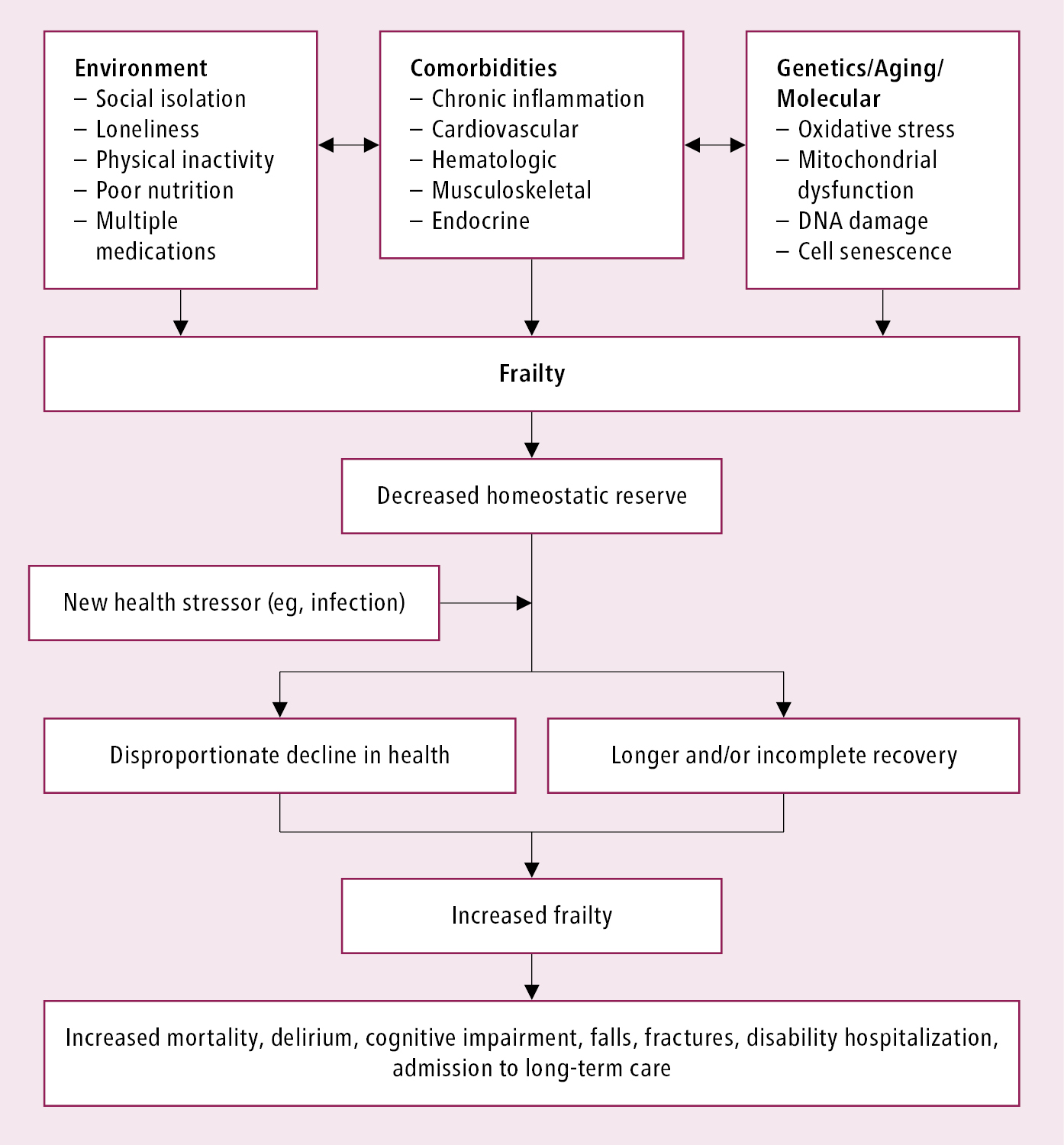

Frailty occurs through a complex interplay of comorbid diseases, aging, genetics, as well as social and environmental factors (Figure 8.2-2). Although frailty increases with age, it is distinct from chronologic age and is more analogous to the “biologic age” of an individual.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

Frailty is a complex state with varied clinical features depending on whether the individual is physically, cognitively, physiologically, or socially frail, for example. The initial symptoms can range from nonspecific (fatigue, weight loss, frequent infections) to specific events such as falls, delirium, incontinence, fluctuating immobility, or sensitivity to medication effects. Therefore, when an older adult presents with one of these events, it is important to consider underlying frailty as a cause.

In addition to these symptoms, 2 conceptual models of frailty are commonly used to describe the features of frail individuals:

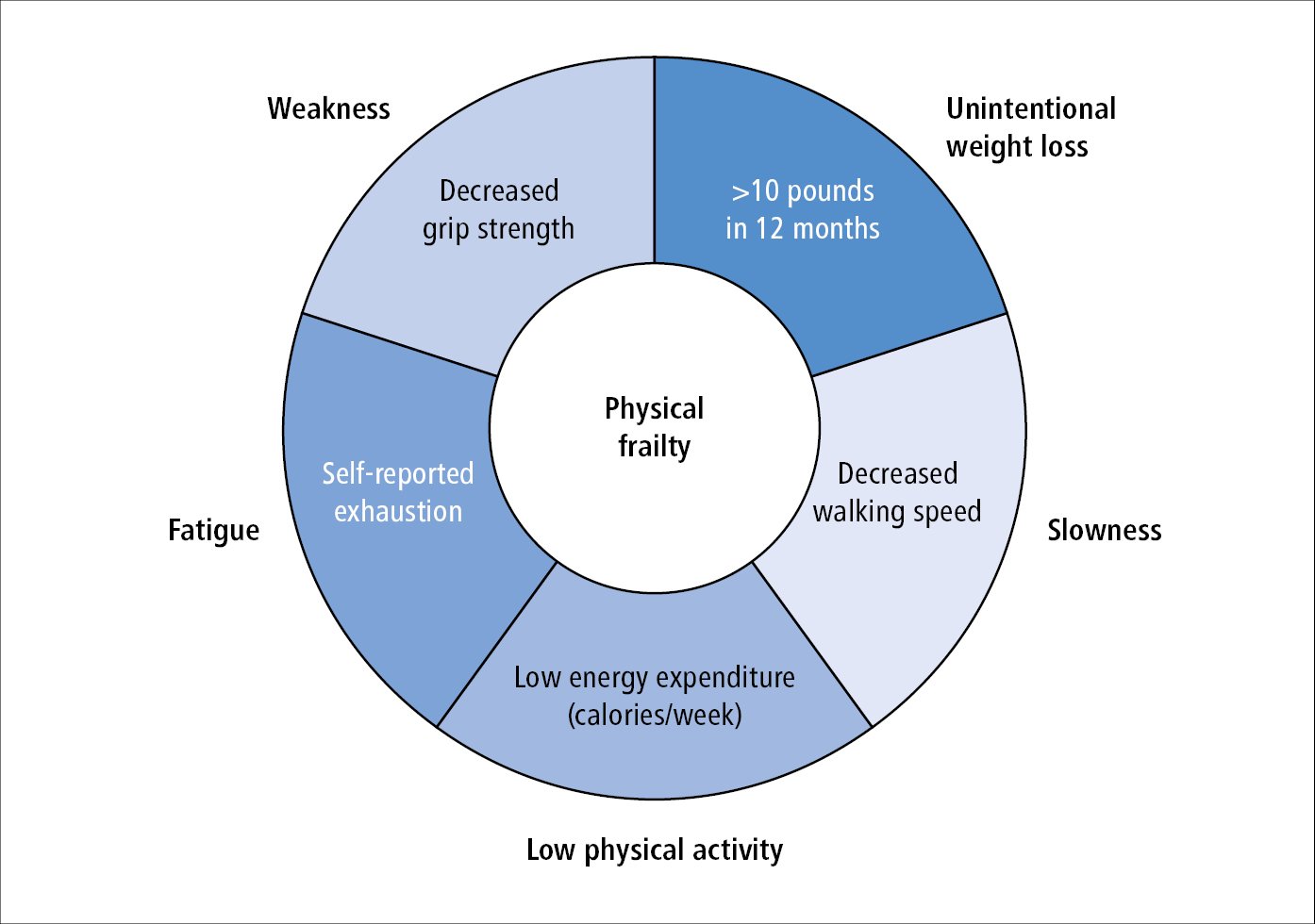

1) The Fried phenotype model (physical frailty): The presence of unintentional weight loss, self-reported exhaustion, low physical activity, slow gait speed, and weak grip strength (Figure 8.2-3). The presence of ≥3 characteristics deems an individual as frail; 1 or 2 factors, as prefrail; and no factors, as robust. This model is typically used in research.

2) Cumulative deficit model or frailty index is based on the supposition that the more impairments an individual has across multiple domains, the more likely they are to be frail. Frailty indices typically include 30 to 80 symptoms (ie, fatigue, memory changes, mood problems), signs (ie, falls, sleep changes, gait changes), abnormal laboratory test results (ie, low albumin levels), comorbid diseases (ie, stroke, myocardial infarction [MI], chronic heart failure [CHF]), and disabilities (ie, problems getting dressed or bathing). This approach allows frailty to be graded on a spectrum. A more evolved description of the frailty scale is available at www.mdcalc.com and www.dal.ca.

In both models, higher levels of frailty are associated with greater impairment in the homeostatic reserve and vulnerability. However, an individual’s current level of frailty is not static; it can improve (see Comprehensive Treatment Plan, below) or worsen (see Patient-Centered Care Planning, below). As the recognition of frailty improves, earlier treatment of underlying causes may lead to more effective reversal.

ScreeningTop

Adults aged >65 years presenting with geriatric syndromes, such as falls, delirium, cognitive changes, or functional decline, should be screened for frailty. There are many tests available; however, their accuracy varies. Clinicians can consider using one of the screening tests listed below, although these tests primarily detect physical frailty and may therefore miss frailty that arises primarily from other domains, such as cognitive or socioeconomic concerns.

Screening tests for physical frailty:

1) 4-meter walk test: Measure the time, in seconds, that it takes the patient to walk 4 meters in a straight line, using their usual gait aids if needed. More than 5 seconds is an abnormal result.

2) Timed up and go (TUG) test: Measure the time, in seconds, that it takes the patient to stand up from a chair, walk 3 meters, turn, walk back to the chair, and sit down. More than 10 seconds is considered abnormal.

Additionally, given that the frailty syndrome can be due to cognitive frailty—in addition to or separately from physiologic, social, or physical frailty—we recommend screening for cognitive impairment. Perform a validated cognitive screening test, such as the standardized Mini-Mental State Examination (sMMSE) (no longer available in the public domain but can be reviewed at the Government of the British Columbia website) or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (www.mdcalc.com) in adults aged >65 years who present with frailty or subjective cognitive complaints (see Dementia).

Consider the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS) if cultural or language differences may affect performance (www.demetia.org.au).

DiagnosisTop

If the 4-meter walk test or TUG results are abnormal, a detailed assessment should be undertaken to diagnose frailty. The gold standard for diagnosis is comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA). The CGA is a medical consultation carried out by a multidisciplinary health-care team, which may include a geriatrician, occupational therapist, pharmacist, physical therapist, and/or nurse. When time or resources do not permit for a CGA, there are several other tools that can be used in combination with clinical judgement:

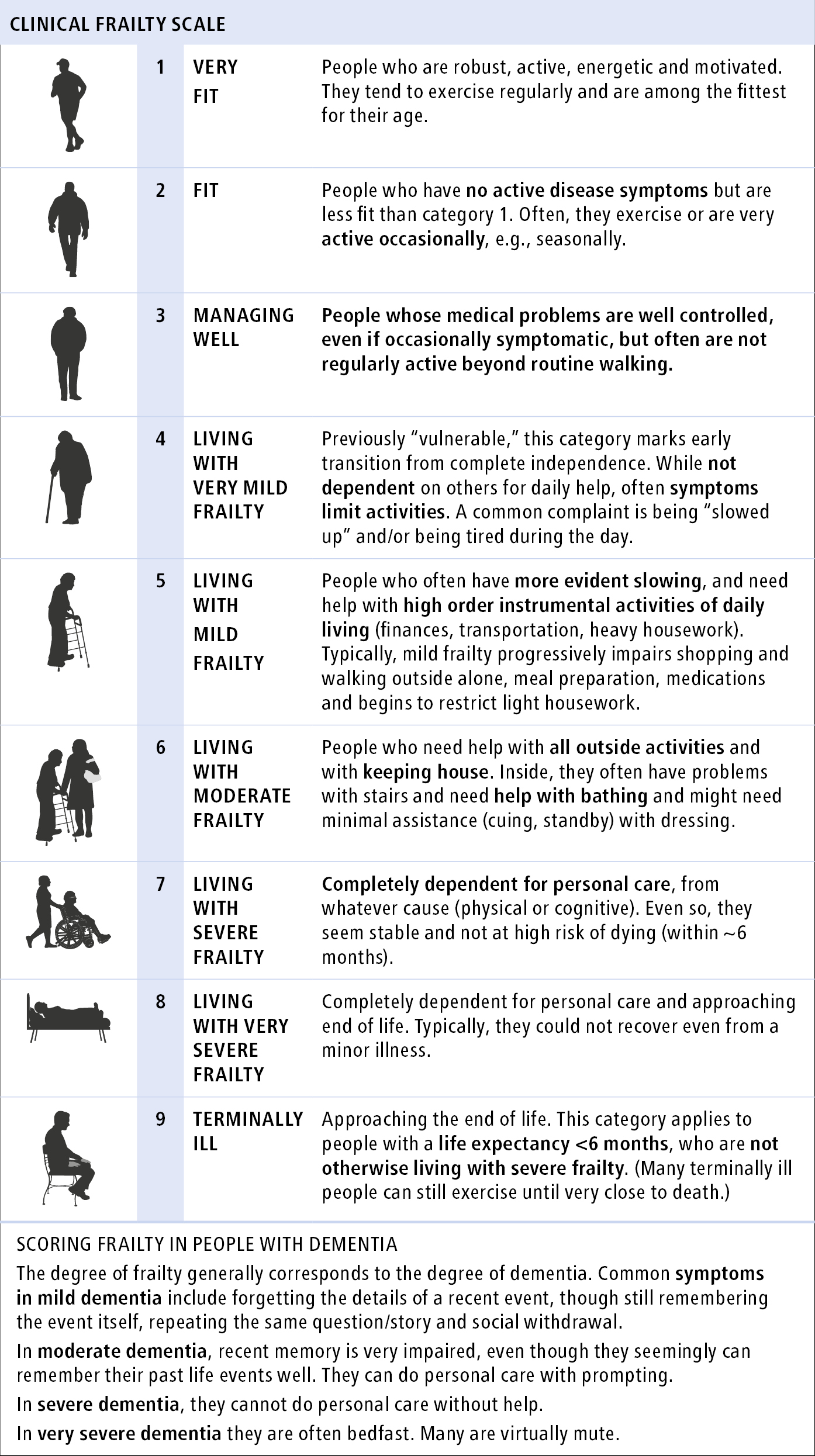

1) Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) (Figure 8.2-4; www.dal.ca).

2) FRAIL scale (www.mass.gov).

3) Edmonton Frailty Scale (EFS) (www.alberthealthservices.ca).

The diagnosis of frailty is based on the patient’s baseline status ≥2 weeks before the current presentation. This is particularly important in acute-care medicine, where a patient’s acute illness can make them appear frailer than they are, due to a transiently reduced function (a false positive). For tips on how to use the CFS properly, visit CFS Guidance & Training from Dalhousie University’s Geriatric Medicine Research.

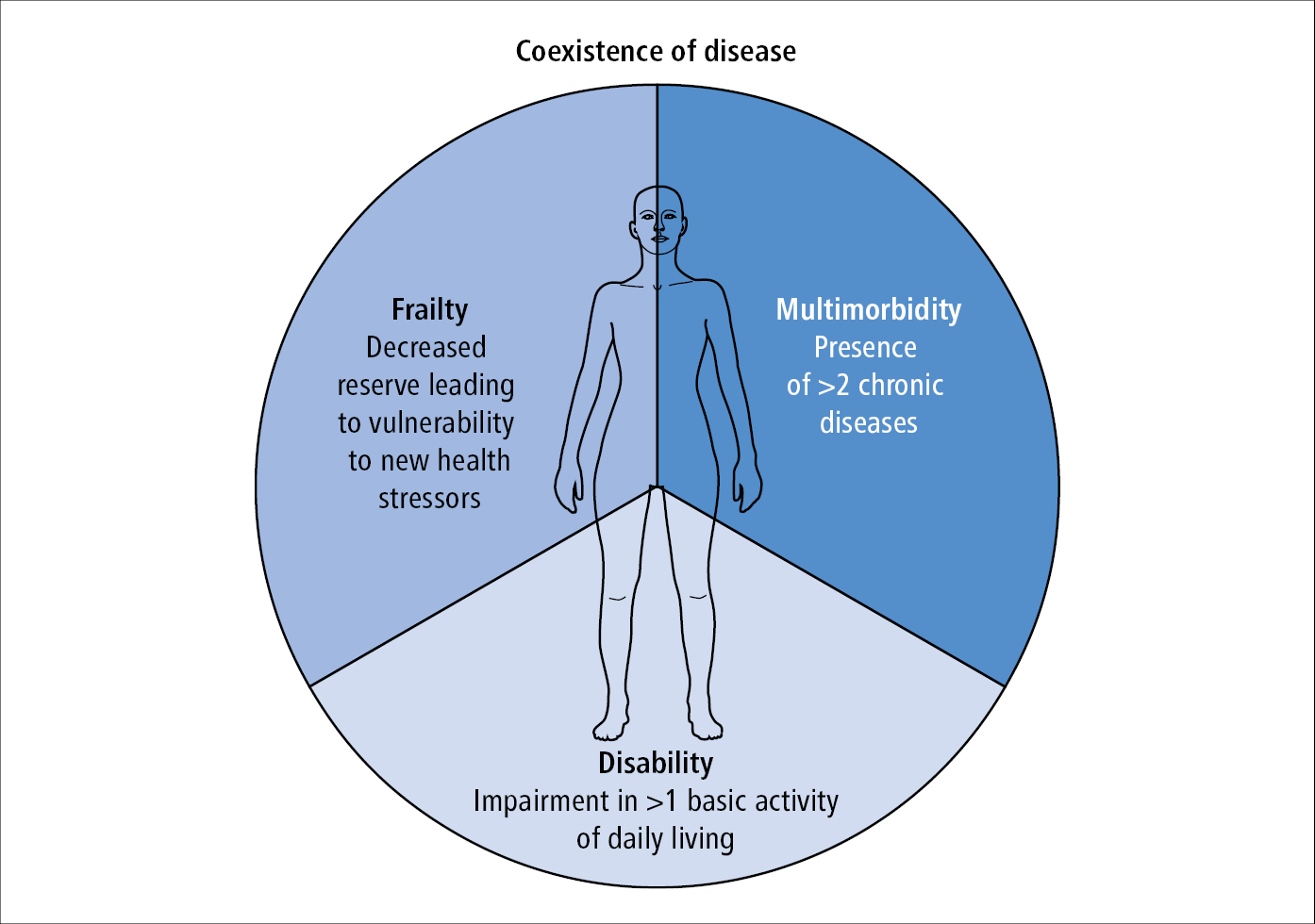

The differential diagnosis of frailty includes disability and multimorbidity, where comorbidity could be defined as having ≥2 of the following diseases: MI, angina, CHF, claudication, arthritis, cancer, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and disability as restriction in ≥1 of the activities of daily living. While multimorbidity, disability, or both can lead to or be associated with frailty, not all individuals with multimorbidity or disability are frail (Figure 8.2-5).

TreatmentTop

There are 3 main objectives of frailty management:

1) Identify and treat modifiable conditions that can contribute to the presentation of frailty: Table 8.2-1.

2) Develop a comprehensive treatment plan to improve or slow frailty progression: Table 8.2-2.

3) Consider frailty in patient-centered care planning.

Identify and treat modifiable conditions that can contribute to the presentation of frailty (Table 8.2-1). These can be identified during the assessment for frailty through a detailed history taking, physical examination, and blood tests.

Clinicians should develop a comprehensive care plan addressing cognitive health, polypharmacy, and the physical aspects of frailty (Table 8.2-2). Of these, the strongest evidence exists for physical exercise.Evidence 1Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity and risk of bias. Travers J, Romero-Ortuno R, Bailey J, Cooney M-T. Delaying and reversing frailty: a systematic review of primary care interventions. Br J Gen Pract. 2019 Jan;69(678):e61-e69. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X700241. Epub 2018 Dec 3. PMID: 30510094; PMCID: PMC6301364. For frailty associated with significant complexity, diagnostic uncertainty, or challenging symptom control, consider a referral to interprofessional health-care specialists with training in geriatric medicine, such as geriatricians, specialists in care of the elderly, geriatric psychiatry, and/or occupational and physical therapists, nutritionists, or social workers. Always consider a balance between benefits of individual medications and the risk of polypharmacy (especially as such balance may change with increasing frailty).

Patient-Centered Care Planning

Identification of frailty is important when counseling patients on decisions related to treatments and goals of care for other medical conditions. Frailty lowers an individual’s homeostatic reserve, which often impacts the risks and benefits of treatment for other acute or chronic diseases, which can lead to unnecessary harm.

A holistic risk-benefit assessment should take into account an individual’s frailty status, preferences, and biopsychosocial context when considering treatment of other medical conditions. Many studies do not include patients with severe frailty, likely underestimating the adverse events anticipated in this population given that a lower homeostatic reserve is a core feature. This predisposes them to disproportionate changes in health status from stressors such as minor surgeries or new medications (Figure 8.2-2). Patients with frailty may also take longer to recover following an acute illness or procedure, and clinicians should ensure patients with frailty are given adequate time for rehabilitation.

Informed consent should include identification of frailty and the impact on long-term prognosis, risks of medical and surgical interventions including the possibility of increased frailty, and expected benefits based on the individual’s degree of frailty. This does not mean that patients with frailty should not receive disease-specific guideline care, but rather that their care should be more nuanced and individualized to their holistic circumstances.

Prognosis and ComplicationsTop

Increased levels of frailty are associated with worse prognosis across many health domains and care settings, due to the association between frailty and a decreased reserve to compensate for a new health stressor. This can be characterized by a seemingly disproportionate change in health status with a relatively minor stressor or slow recovery from illness.

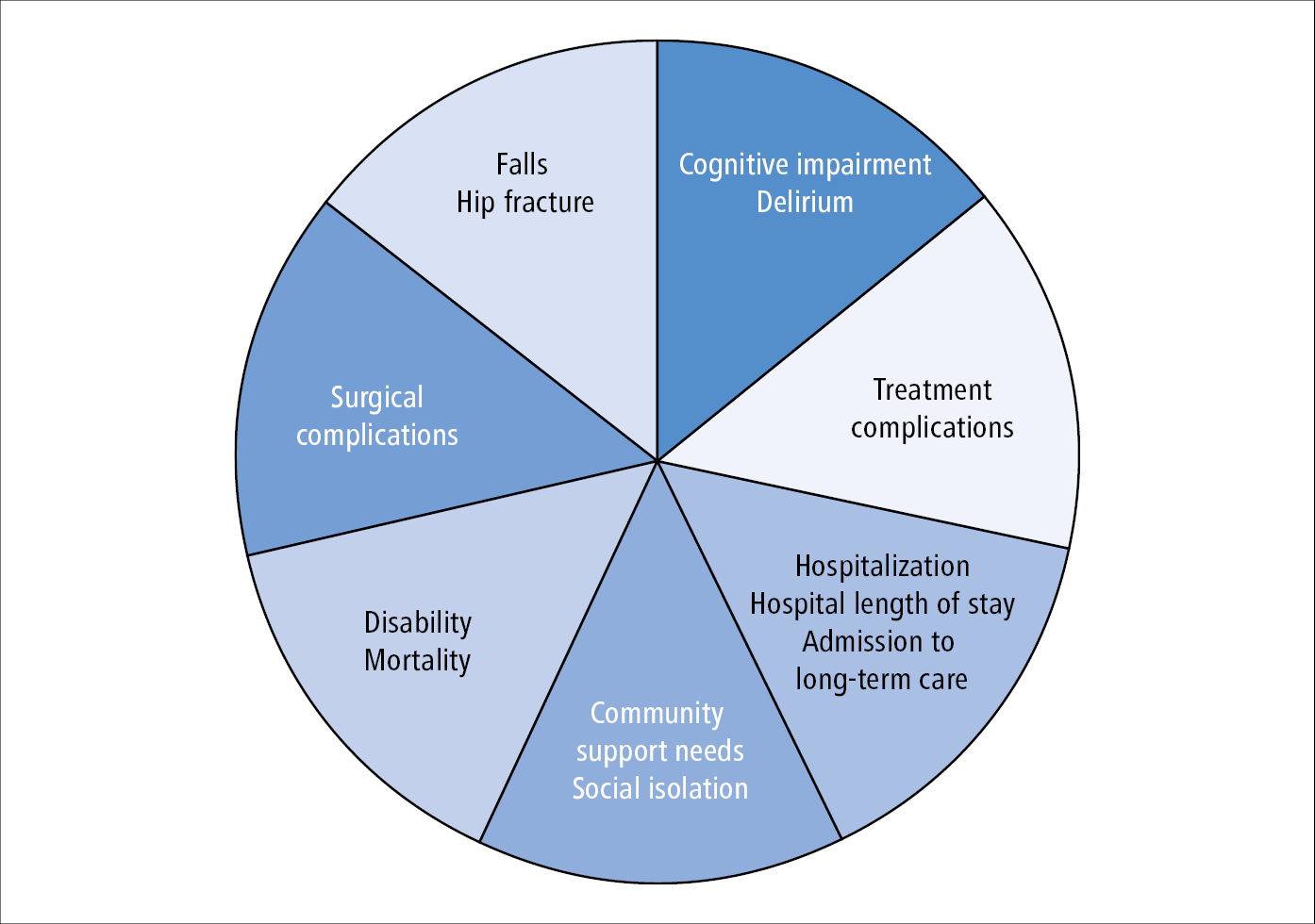

Frailty impacts patient and system-level outcomes (Figure 8.2-6). It is important to note that it is not the presence of frailty, but the degree of frailty that often dictates to what extent these outcomes are realized. With recognition of frailty, some of these outcomes may be preventable or reversible.

PreventionTop

The Canadian Frailty Network recommends the following frailty prevention strategies:

1) Activity:

a) Exercise: Referral for a multicomponent physical activity program that includes balance training, strength training, and aerobic exercise.

b) Sleep: The recommended duration of sleep for older adults is 7 to 8 hours per night.

2) Vaccination: Older adults should receive influenza, shingles, and pneumonia vaccines.

3) Medication optimization: Use criteria such as Beers or STOPP/START to limit inappropriate polypharmacy.

4) Interaction: Recommend maintaining social activities such as clubs and volunteer programs to avoid loneliness (the subjective feeling of being alone) and social isolation (physical isolation from others).

5) Diet and nutrition:

a) Follow a healthy diet such as the Mediterranean diet.

b) Obtain an adequate calcium intake from diet and consider vitamin D supplementation.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Symptom of frailty |

Possible contributing conditions |

Focused approach |

|

Fatigue |

Depression, sleep apnea, CHF, COPD, anemia, hypotension, hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency |

1. Conduct or request a medication review to assess for drugs that could be causing fatigue or weight loss, medication adherence, and proper medication administration (eg, inhalers) 2. On review of systems, ask about depression, sleep, appetite, weight loss, pain, and social isolation 3. On social history, ask about alcohol intake, financial concerns or difficulty making ends meet, and concerns of elder abuse 4. On examination, obtain supine and standing blood pressure, looking for overt or postural hypotension 5. Calculate the patient’s STOP BANG score (www.stopbang.ca) and refer for sleep study as appropriate 6. Order blood tests for CBC, calcium, albumin, TSH, and vitamin B12 and liver function tests. Consider echocardiography or pulmonary function testing if indicated by the overall clinical picture |

|

Weight loss |

Alcohol abuse, swallowing or oral problems, malabsorption, cholecystitis, low-salt/low-cholesterol diet, hyperthyroidism, hypercalcemia, hypoadrenalism, poverty, shopping and meal preparation problems, elder abuse, medication adverse effects | |

|

CBC, complete blood count; CHF, chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone. | ||

|

Target |

Interventions |

|

Cognitive health |

Maintain cognitive health by addressing: 1) Hearing and vision impairment 2) Sleep, with a target of 7-8 h/night 3) Social isolation: Family, friends, and community groups 4) Diet and exercise (see below) |

|

Medication review |

Optimize appropriate use of medications in older adults using: 1) START/STOPP criteria (www.valeofyorkccg.nhs.uk or www.mm.wirral.nhs.uk) 2) Beers Criteria (www.pharmacytoday.org) 3) Deprescribing.org resources (www.deprescribing.org) |

|

Diet and exercise |

Address physical sarcopenia (defined as the presence of low skeletal muscle mass and low muscle strength): 1) Exercise: Community exercise program that includes a resistance-based training componenta 2) Protein supplementationb and nutrition education (consider community meal programs such as Meals-on-Wheels) 3) Vitamin D supplementation if deficiency is present |

|

a Exact combination of aerobic, resistance, and/or balance training is unclear. b Optimal total daily protein intake (dietary plus supplemental protein) is 1.2 to 1.5 g of protein/kg of body weight. |

|

Figure 8.2-1. The relation between frailty and reserve conceptualized as a set of scales.

Figure 8.2-2. Pathophysiology of frailty. Adapted from Lancet. 2013;381:752-762.

Figure 8.2-3. Physical frailty based on the Fried phenotype model. Adapted from J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001 Mar;56(3):M146-56.

Figure 8.2-4. Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS). The degree of frailty is based on an overall fitness summary and requires clinical judgement. CFS is not validated in younger patients or those with lifelong or single-system disability. Source: Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005;173:489-495; with permission from Dalhousie University, Geriatric Medicine Research.

Figure 8.2-5. The differential diagnosis for frailty includes disability and multimorbidity. These entities can exist in isolation or concurrently with each other. Based on J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001 Mar;56(3):M146-56.

Figure 8.2-6. Patient and system-level outcomes of frailty. With increased frailty patients may experience increased rates of these outcomes.