Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 8;381(6):552-565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1806651. PMID: 31390501.

Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, et al; Endocrine Society. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;99(6):1915-42. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1498. PMID: 24893135.

Steen O, Fernando J, Ramsay J, Prebtani APH. An Unusual Case of a Composite Pheochromocytoma With Neuroblastoma. J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;4(1-2):39-46.

Nerenberg KA, Zarnke KB, Leung AA, et al; Hypertension Canada. Hypertension Canada's 2018 Guidelines for Diagnosis, Risk Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment of Hypertension in Adults and Children. Can J Cardiol. 2018 May;34(5):506-525. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.02.022. Epub 2018 Mar 1. PMID: 29731013.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Pheochromocytoma (PCC) and paraganglioma (PGL) are catecholamine-secreting tumors that arise from chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla and extra-adrenal sympathetic ganglia, respectively. They account for <0.5% of all causes of hypertension. The majority of these rare tumors occur sporadically. Approximately 40% occur as part of a familial syndrome, 10% are bilateral, 10% are extra-adrenal, 10% are found in children, 10% are recurrent, and <10% are malignant.

Hereditary PCC/PGL syndromes include multiple endocrine neoplasia types 2 and 3 (MEN 2/MEN 2a MEN 3/MEN 2b), von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) (cerebroretinal angiomatosis), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), Carney triad (gastrointestinal stromal tumor, pulmonary chondromas, and functional extra-adrenal paragangliomas), and mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), TMEM127, and MAX genes.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

The classic triad, in addition to hypertension, consists of paroxysmal headaches, palpitations, and sweating. Other symptoms and signs include paroxysmal hypertension, pallor, postural hypotension, anxiety, weight loss, and panic attacks (see Table 6.1-1). Additional clues to consider screening for PCC/PGL are unexplained variability of blood pressure (BP); paradoxical BP response to anesthesia, surgery, or certain drugs; extremes of age; severe hypertension, hypertension resistant to >3 drugs; syndromes associated with PCC or PGL; unexplained dilated cardiomyopathy; or a family history suggestive of a hereditary PCC or PGL syndrome.

Complications include cardiomyopathy, heart failure, end-organ damage due to hypertension, arrhythmias, and death if the condition is uncontrolled or untreated.

DiagnosisTop

Screening should be considered in patients with suggestive clinical features (see above) and if there is an incidentally discovered adrenal or retroperitoneal mass with ≥10 Hounsfield unit (HU) attenuation on unenhanced computed tomography (CT) or low washout on a contrast-enhanced study, or if the patient is known to be a carrier of disease-causing genetic mutations of syndromes (eg, mutations in RET [MEN 2, MEN 3], VHL, SDHx, TMEM127, MAX, or NF1 genes).

1. Laboratory tests: Elevated 24-hour urine fractionated metanephrine levels and plasma metanephrine levels have a high sensitivity. Mild elevations can be nonspecific and nondiagnostic, but elevations >2 to 3 × the upper limit of normal (ULN) may be diagnostic. Many medications and other substances can interfere with biochemical results and should be discontinued 1 to 2 weeks prior to testing, if possible. These include acetaminophen (INN paracetamol), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), levodopa, amphetamines, most psychoactive agents, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), cocaine, beta-blockers, alpha-blockers, and sympathomimetics, among others (see Table 6.1-2). Always ask the patient about herbal therapies, supplements, and nonprescribed agents. If the suspicion is still high and the results are equivocal on repeat testing, consideration can be given to clonidine suppression testing of plasma normetanephrines, usually performed in specialized endocrinology settings.

2. Anatomic imaging: After making the diagnosis based on clinical and biochemical criteria, it is critical to localize the tumors with imaging studies. Imaging should not be pursued prior to clinical and biochemical confirmation. Localization is initially by contrast-enhanced CT (high sensitivity; of note: unenhanced attenuation on CT >10 HU suggests pheochromocytoma but does not exclude malignancy) or T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (high sensitivity and moderate specificity) of the abdomen. If this fails to locate a tumor, proceed to whole-body CT or MRI to localize extra-abdominal PGL.

3. Functional/molecular/radionuclear imaging (done in specialized settings): Functional/molecular/radionuclear imaging should be done if the results of anatomic imaging are equivocal or in case of searching for tumors that may be extra-adrenal, multiple/bilateral suspected tumors, primary adrenal tumor sized >10 cm, or metastatic disease. Imaging modalities include scintigraphy with 68Ga-DOTATATE positron emission tomography with computed tomography (PET-CT), 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy, or 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET-CT.

1) 68Ga-DOTATATE PET-CT can effectively localize the tumor and potential metastases with high sensitivity unless the tumor is poorly differentiated.

2) 123I-MIBG can also be used to localize the tumor and potential metastases, although it is less sensitive than 68Ga-DOTATATE PET-CT. Medications such as labetalol, TCAs, and phenothiazines should be withheld for 4 to 6 weeks prior to imaging to reduce the risk of false-negative results.

3) 18FDG PET-CT is occasionally helpful if the above-listed functional/molecular imaging studies are negative and there is suspicion of a poorly differentiated tumor.

Results of molecular/functional/radionuclear imaging alone cannot be used as a surgical indication and must always be correlated with CT or MRI findings as well as clinical and biochemical data.

4. Genetic testing (done in specialized settings): Genetic testing can be considered in those with confirmed PCC or PGL who are aged <50 years, those who have clinical features of a genetic syndrome associated with PCC or PGL, those who have a family history of PCC/PGL, and those with multiple tumors, malignant tumors, or bilateral tumors.

Other causes of (resistant or refractory) hypertension and “spells” should always be excluded. The list of differential diagnoses includes thyrotoxicosis, carcinoid, panic attacks, cluster headaches, migraine headaches, use or withdrawal of certain drugs and illicit substances, autonomic dysfunction, and pseudopheochromocytoma (paroxysmal hypertension with a negative biochemical evaluation for pheochromocytoma).

TreatmentTop

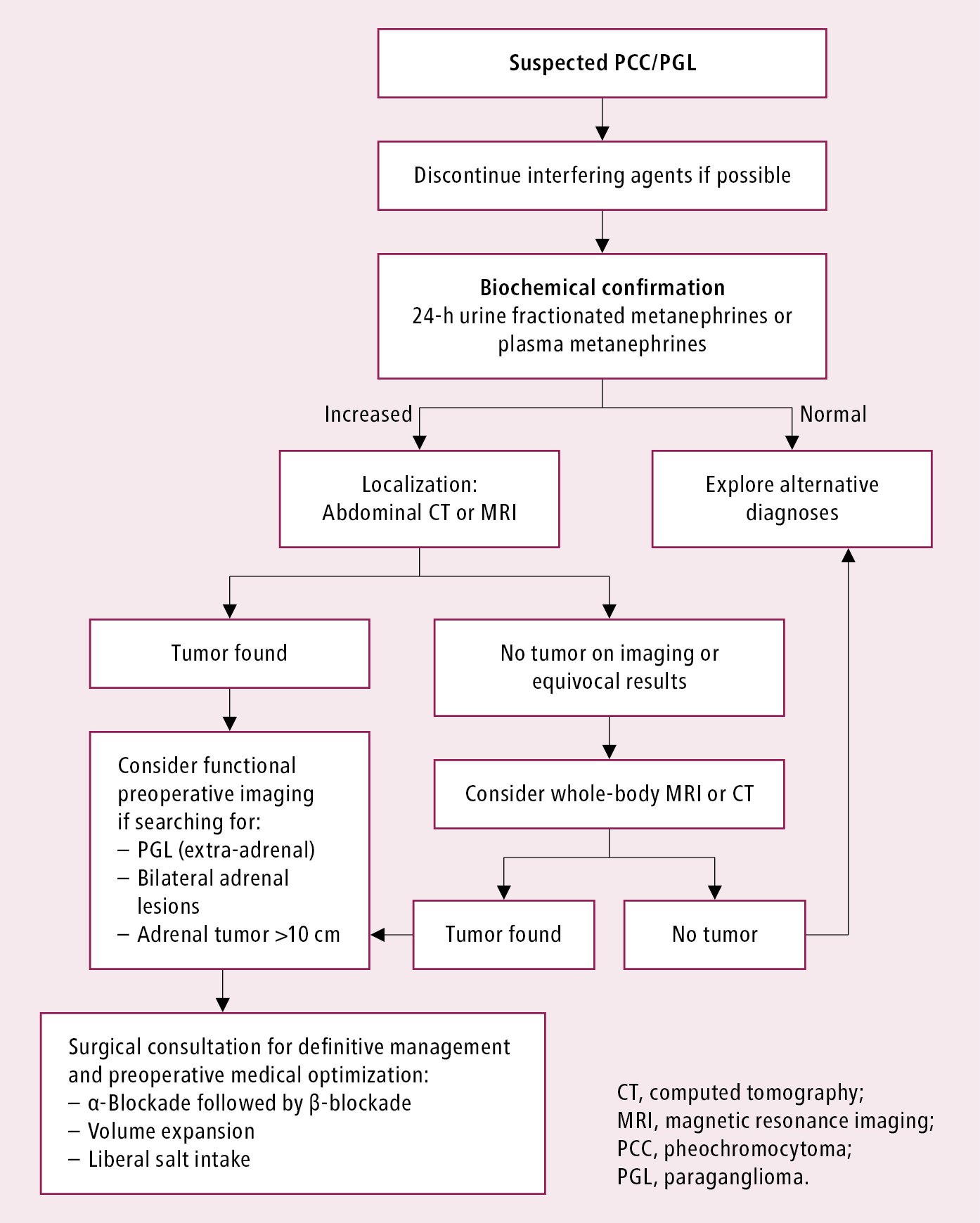

Diagnostic algorithm for suspected PCC or PGL: Figure 6.1-1.

Surgical resection of the tumor is the mainstay of therapy. Surgery should be undertaken after medical optimization. The goals of preoperative medical therapy include optimal BP control, heart rate control, and volume expansion, as these patients are often volume contracted, to avoid perioperative morbidity and mortality associated with hypertensive crises, malignant arrhythmia, multiorgan failure.

1. Medical optimization: Optimal BP control with combined alpha- and beta-blockade is essential prior to planned surgery along with adequate hydration with generous fluid and sodium intake. Target BP should be in the low-normal range for age (<130/80 mm Hg and systolic BP >110 mm Hg in a standing position), while avoiding significant orthostatic hypotension or its symptoms. It is important to use alpha-blockade first, starting ≥10 to 14 days before surgery, and then follow with beta-blockade 3 to 4 days later (for controlling the risk of tachycardia and arrhythmia) to mitigate unopposed alpha-receptor stimulation, which could lead to catastrophic hypertension and cardiopulmonary decompensation. Other agents that could be added include dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), but it is best to avoid diuretics if possible. Anesthesia consultation is also imperative preoperatively, along with ensuring the availability of intraoperative IV phentolamine, IV nitroprusside, and IV beta-blockers, if needed.

1) Alpha-adrenergic blockade: A nonselective alpha-blocker may be used, for instance, phenoxybenzamine 10 mg bid as a starting dose and titrated up to 60 mg bid. Alternatively, a selective alpha-1 adrenergic blocker such as doxazosin at a starting dose of 1 to 2 mg daily and titrated up to 16 mg bid may be used.

2) Beta-adrenergic blockade: Beta-blocker therapy is used to control tachycardia. Beta-blockers should be initiated a few days after adequate BP control has been achieved with alpha-blockade to attain a target heart rate of 60 to 80 beats per minute.

2. Surgery:

1) PCC: Laparoscopic localized adrenalectomy by an experienced adrenal surgeon may be done for the majority of patients, especially if a small, unilateral, intra-adrenal tumor with nonmalignant features is found on imaging. Other patients may require open laparotomy.

2) PGL requires resection by a surgeon experienced in the particular site(s) where the tumor is located.

Postoperative CareTop

1. In many patients antihypertensive agents can be stopped right away postoperatively with careful BP monitoring.

2. Patients may need a significant amount IV crystalloids due to postoperative hypotension.

3. Assess plasma and/or 24-hour urine metanephrine levels in a few weeks and then yearly for ≥10 years.

4. Repeat imaging periodically in patients with a “silent/nonfunctional” tumor or positive biochemical testing.

PrognosisTop

In PCC, adrenalectomy provides cure for the majority of patients if the tumor is not malignant. However, PCC may recur in ≤10% of patients and metastatic disease may also occur after surgical removal. In PGL, the prognosis depends on the size, site, completeness of resection, and malignant potential of the tumor.

Malignant/metastatic PCCs/PGLs have a poorer prognosis and may require other therapies in a specialized multidisciplinary setting if they are progressive, persistent, or symptomatic. Treatments may include radionuclide therapy, somatostatin analogues (SSAs), tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), liver-directed therapy, radiotherapy, and/or chemotherapy. In addition, these patients may also have underlying essential hypertension requiring usual antihypertensive therapy (see Essential Hypertension). Therefore, long-term follow-up is necessary.

TABLES AND FIGURESTop

|

Clinical finding |

Incidence (if known) |

|

Hypertension |

90% |

|

Headache |

80% |

|

Perspiration |

71% |

|

Palpitations |

64% |

|

Pallor |

42% |

|

Postural hypotension |

10%-50% |

|

Paroxysms/“spells” |

50% |

|

|

Normetanephrines |

Metanephrines | ||

|

Plasma |

Urine |

Plasma |

Urine | |

|

Acetaminophen |

↑↑ |

↑↑ |

No change |

No change |

|

Labetalol |

No change |

↑↑ |

No change |

↑↑ |

|

Sotalol |

No change |

↑↑ |

No change |

↑↑ |

|

Alpha-methyldopa |

↑↑ |

↑↑ |

No change |

No change |

|

Tricyclic antidepressants |

↑↑ |

↑↑ |

No change |

No change |

|

Phenoxybenzamine |

↑↑ |

↑↑ |

No change |

No change |

|

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

↑↑ |

↑↑ |

↑↑ |

↑↑ |

|

Sympathomimetics |

↑ |

↑ |

↑ |

↑ |

|

Levodopa |

↑ |

↑↑ |

↑ |

↑ |

|

Buspirone |

No change |

No change |

↑↑ |

↑↑ |

|

Cocaine |

↑↑ |

↑↑ |

↑ |

↑ |

Figure 6.1-1. Diagnostic algorithm for suspected pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma.