Fleseriu M, Auchus R, Bancos I, et al. Consensus on diagnosis and management of Cushing’s disease: a guideline update. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021 Dec;9(12):847-875. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00235-7. Epub 2021 Oct 20. PMID: 34687601; PMCID: PMC8743006.

Varlamov EV, Langlois F, Vila G, Fleseriu M. MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Cardiovascular risk assessment, thromboembolism, and infection prevention in Cushing’s syndrome: a practical approach. Eur J Endocrinol. 2021 Apr 22;184(5):R207-R224. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-1309. PMID: 33539319.

Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al; Endocrine Society. Treatment of Cushing’s Syndrome: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Aug;100(8):2807-31. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1818. Epub 2015 Jul 29. PMID: 26222757; PMCID: PMC4525003.

Lacroix A, Feelders RA, Stratakis CA, Nieman LK. Cushing’s syndrome. Lancet. 2015 Aug 29;386(9996):913-27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61375-1. Epub 2015 May 21. PMID: 26004339

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Cushing syndrome is a clinical syndrome that includes signs and symptoms resulting from longstanding exposure of tissues to excess glucocorticoids.

Cushing syndrome is classified based on etiology.

1. Exogenous Cushing syndrome is caused by administration, by any route, of glucocorticoids at doses exceeding their physiologic levels. This is the most common cause of Cushing syndrome.

2. Endogenous Cushing syndrome results from adrenal overproduction of glucocorticoids.

1) Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)–dependent Cushing syndrome (80% of cases) results from excess ACTH production.

a) Pituitary adenoma/neuroendocrine tumor (PitNET) (70%), also known as Cushing disease.

b) Ectopic ACTH secretion (10%): Extrapituitary neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) (bronchial, thymic, gastrointestinal (GI), and pancreatic tumors, small cell lung carcinoma, medullary thyroid cancer, and pheochromocytoma/paragangliomas).

c) Ectopic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) secretion (0.5%).

d) Pituitary carcinoma (very rare).

2) ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome (20% of cases): Excess cortisol inhibits CRH and ACTH secretion. Primary adrenal tumors are more commonly unilateral:

a) Adrenal adenoma (10%).

b) Adrenal carcinoma (10%) may lead to excess cortisol production alone or with androgen and aldosterone overproduction. It is often nonfunctioning.

c) Bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (BMAH) (<1%) is characterized by large multiple nodules sized >1 cm. It is usually sporadic or, less frequently, familial (ARMC5 variant and KDM1A gene inactivation in patients with gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP)–dependent BMAH). Pathophysiology is related to aberrant G protein–coupled receptors activated by atypical stimuli, such as GIP, catecholamines, antidiuretic hormone, thyroid-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, angiotensin II, serotonin, and human chorionic gonadotropin. It can also be associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1), familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), and McCune-Albright syndrome (see below).

d) Bilateral micronodular adrenal hyperplasia (primary pigmented nodular adrenal disease [PPNAD]) is characterized by nodule diameter <1 cm. It may be sporadic or occur as part of Carney complex (a hereditary autosomal dominant condition associated with abnormalities in various tissues such as cardiac myxoma, lentiginosis, breast ductal adenoma, and testicular tumors).

e) McCune-Albright syndrome is a rare form of BMAH that presents in infancy or childhood. It is sporadic and characterized by polyostotic fibrous dysplasia with café au lait spots, sexual precocity, and other endocrine and nonendocrine disorders. It can also result in the growth hormone causing acromegaly in addition to Cushing syndrome.

Severe Cushing syndrome (SCS) is defined by markedly elevated 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC) (>4 times the upper limit of normal [ULN]) or serum random cortisol levels (>41 microg/dL or 1100 nmol/L) in association with recent-onset complications such as heart failure; GI bleeding; sepsis (including opportunistic infections); psychosis; venous thromboembolism (VTE); severe myopathy; severe or intractable hypokalemia (<3.0 mmol/L); uncontrolled hypertension, hyperglycemia, or ketoacidosis. Severe Cushing syndrome is considered a medical emergency and requires prompt intervention, since if uncontrolled, it can result in very high morbidity and mortality, mainly because of its cardiometabolic abnormalities and risk of overwhelming infection. Treatment should begin before conducting extensive investigations to determine the cause and localization.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

Signs and symptoms are mainly nonspecific, but some are more distinctive and specific than others. In the list below the more specific features are marked with a hash sign (#; their presence markedly increases the probability of Cushing syndrome), and those more sensitive with an asterisk (*; their absence suggests that Cushing syndrome is less likely).

Symptoms:

1) General: Weight gain* and fatigue/poor exercise tolerance; polydipsia, polyuria, and polyphagia; frequent infections, especially opportunistic (eg, fungal, tuberculosis, Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia [PJP]), often with a severe clinical course.

2) Cutaneous: Skin prone to injury with poorly healing ulcers and easy bruising in nontraumatic areas#.

3) Neurologic and musculoskeletal: Headache, cognitive dysfunction; bone pain, fractures, or osteoporosis/osteopenia at an early age#.

4) Psychiatric: Emotional instability*, depression*, psychotic conditions in severe disease*.

5) Cardiovascular: Symptoms of coronary artery disease (CAD), congestive heart failure, edema.

6) GI: Peptic ulcer disease (particularly in patients treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]).

7) Genitourinary: Decreased libido*; erectile dysfunction in men; oligomenorrhea or secondary amenorrhea in women*; acne and hirsutism; nephrolithiasis.

Objective findings:

1) General: Facial plethora*; facial fullness (“round facies”)*; central weight gain and elevated body mass index*; hypertension*, particularly diastolic hypertension (>105 mm Hg)#, edema.

2) Cutaneous: Wide (>1 cm) and depressed atrophic purple striae#; dorsocervical fat pad, supraclavicular fullness#; thin skin (<2 mm)*#, easy spontaneous bruising#; spontaneous cutaneous hemorrhages or purpura#.

3) Neurologic and musculoskeletal: Osteopenia or fracture; proximal muscle atrophy and/or weakness#.

4) Metabolic: Hyperglycemia; hypokalemic alkalosis#.

5) Genitourinary: Hyperandrogenism (hirsutism, acne, alopecia, oligo/amenorrhea) or virilization (rapidly progressive hirsutism, temporal balding, deepening voice, oligo/amenorrhea, male body habitus, and clitoral hypertrophy). In men, feminizing features may be observed (in very rare estrogen-secreting adrenal tumors, but they are rare or mild in adrenal adenoma).

Natural history:

1. Mild autonomous cortisol secretion (MACS) should be suspected in patients with:

1) Adrenal incidentaloma with no previous adrenal history.

2) No clear Cushingoid phenotype (absence of the most specific features of Cushing syndrome).

3) Evidence of ACTH-independent cortisol production; most often based on a 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test (DST), where there is no suppression of cortisol to <50 nmol/L at 8 am and other confirmatory tests of cortisol excess are normal (see Diagnosis, below). The patient may have associated DM, dyslipidemia, hypertension, weight gain, and/or osteoporosis. The risk of progression to overt Cushing syndrome is low in most cases; however, it is associated with increased cardiovascular and bone morbidity.

2. Overt Cushing syndrome: Most features (particularly the specific ones) are present, as described above, and are progressive.

DiagnosisTop

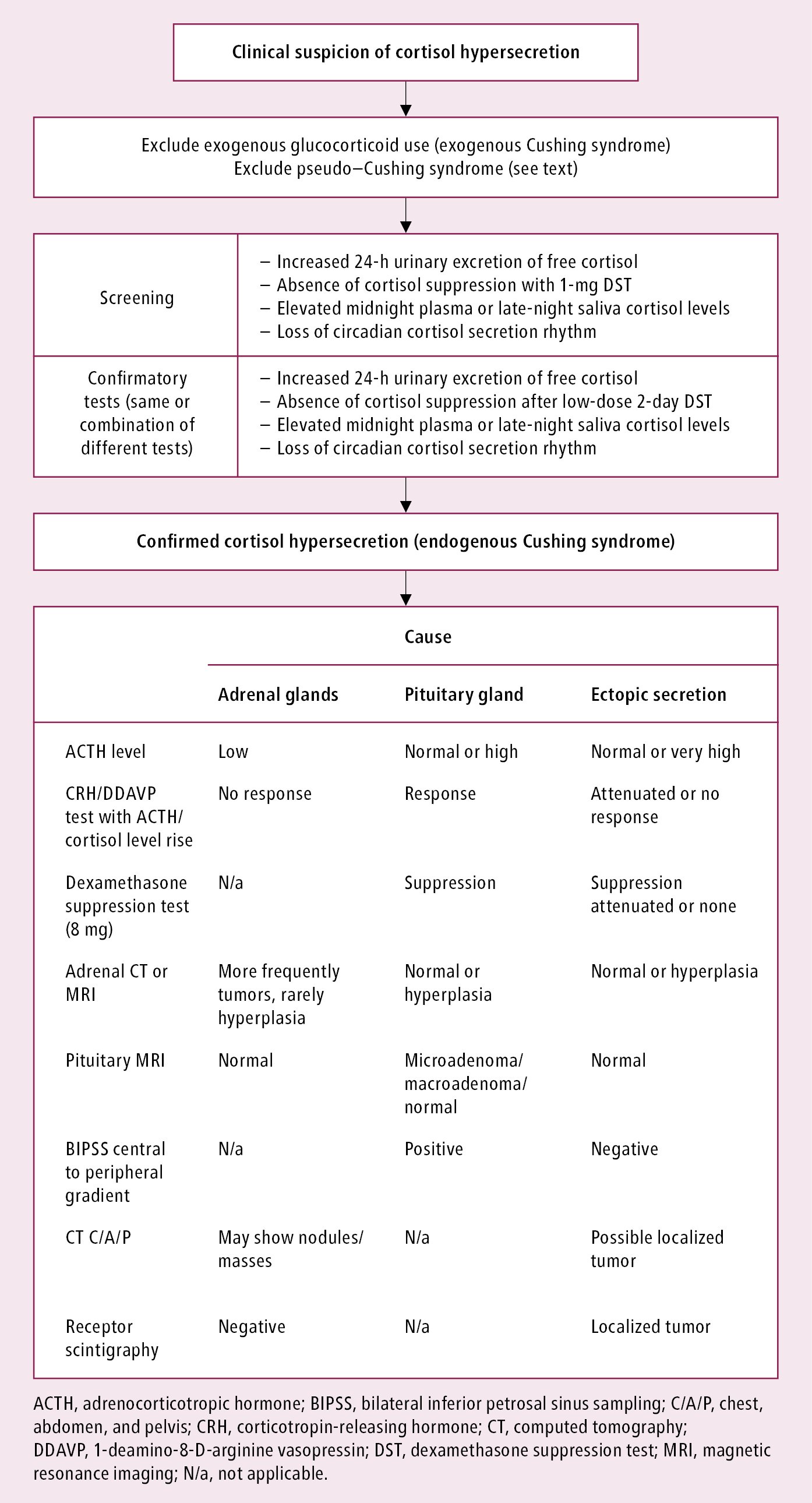

Diagnostic algorithm: Figure 6.1-1. Always exclude prior use of glucocorticoids (all routes) (exogenous Cushing syndrome) and physiologic nonneoplastic hypercortisolism (previously known as pseudo–Cushing syndrome).

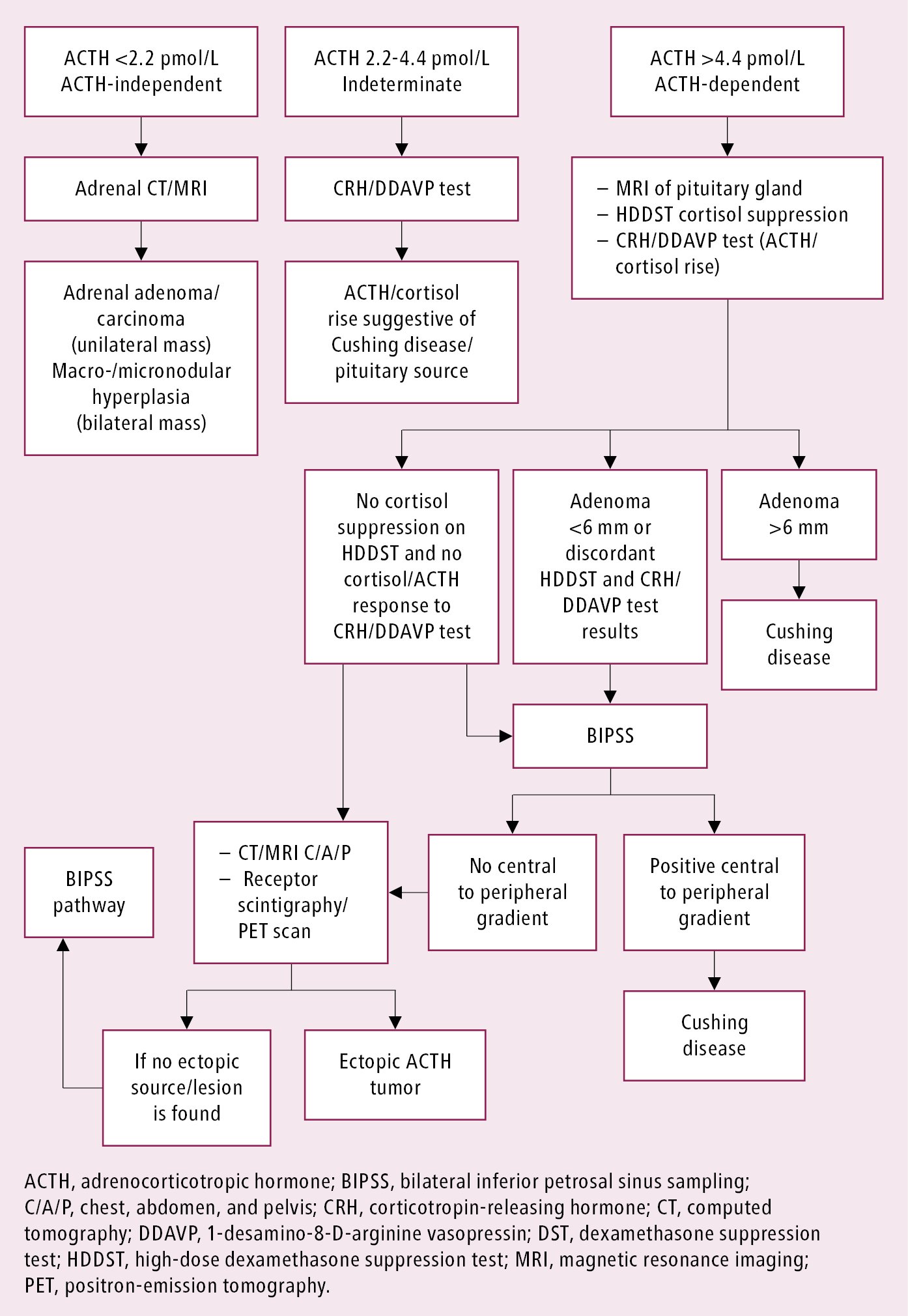

Approach to identifying the cause of endogenous Cushing syndrome: Figure 6.1-2.

Before beginning biochemical evaluation for hypercortisolism, take a detailed history of drug use to exclude exogenous glucocorticoid exposure from any route (eg, nasal, inhaled, topical, rectal) that could explain the signs and symptoms. Also, ask about herbs and supplements that may contain glucocorticoids.

1. Basic biochemical tests:

1) Metabolic panel may reveal hypokalemia, hyperglycemia (impaired glucose tolerance or DM); high total serum cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and triglyceride levels; and low serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels.

2) Complete blood count (CBC) may reveal elevated white blood cell (particularly neutrophilia) and platelet counts. Lymphocyte, eosinophil, and monocyte counts tend to be low. The hemoglobin level is variable.

2. Screening:

1) Inadequate reduction in serum cortisol levels after the 1-mg overnight dexamethasone suppression (DST): Patients are instructed to take oral dexamethasone 1 mg at their bedtime (11 pm to midnight). Fasting serum cortisol levels are measured on the following day between 8 and 9 am, and levels <50 nmol/L (1.8 microg/dL) exclude Cushing syndrome. With any DST, keep in mind any factors that may raise or reduce dexamethasone levels, such as drug interactions (especially those involving P450) and malabsorption, which can result in inaccurate cortisol results due to affected dexamethasone bioavailability. Estrogen and active hepatitis can also elevate total cortisol levels.

2) 24-hour UFC excretion increased to 3 to 4 × ULN suggests the diagnosis of Cushing syndrome (sensitivity and specificity are 95%-100% and 94%-98%, respectively); collection should be repeated at least twice.

3) Elevated late-night salivary cortisol levels at 11 pm to midnight (not useful in shift workers or patients with altered sleep patterns).

4) Loss of the normal circadian cortisol secretion rhythm (the late afternoon or evening serum cortisol levels are generally expected to be <50% of the morning levels).

3. Diagnostic or confirmatory tests:

1) 24-hour UFC excretion (see above).

2) Inadequate reduction in 9 am serum cortisol after the last dose in the 2-day low-dose DST (2-day 2-mg test): Instruct the patient to take oral dexamethasone 0.5 mg every 6 hours for 2 days (usually at 9 am, 3 pm, 9 pm, and 3 am on each day, for a total of 8 doses). The response is considered normal when the 9 am cortisol (6 h after the last dose) is <50 nmol/L (90%-100% sensitivity).

3) Elevated late-night salivary cortisol levels (see above).

4) Loss of the normal circadian cortisol secretion rhythm (see above).

Note that different collection methods and assays available for the measurement of cortisol exist and results may vary. When performing a diagnostic workup, it is important to evaluate the assays available at each center ensure precise sample collection with accurate timing, and collaborate closely with clinical biochemists.

Ensure that 2 to 3 tests are performed to establish the diagnosis of Cushing syndrome before going into localization studies.

4. Tests to identify causes of Cushing syndrome: Once hypercortisolism is documented, the next step is to determine if it is ACTH dependent (ACTH secreting) or ACTH independent (adrenal). This is done by measuring serum ACTH levels.

1) Step 1: Serum ACTH (repeat measurements). Serum ACTH levels <2.2 pmol/L indicate ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome (adrenal source), whereas serum ACTH levels >4.4 pmol/L indicate ACTH-dependent Cushing syndrome. In patients with serum ACTH levels 2.2 to 4.4 pmol/L, the CRH or desmopressin) stimulation test (see below) may be useful to distinguish the ACTH dependence.

2) Step 2 (not needed if there is clearly ACTH-independent hypercortisolism): IV CRH (1 microg/kg) or IV desmopressin (10 microg) stimulation, and/or high-dose DST.

a) The IV CRH or desmopressin stimulation test involves stimulation of ACTH secretion and indirect stimulation of cortisol secretion with CRH or desmopressin. This test can be helpful if the ACTH level is equivocal (ie, 2.2-4.4 pmol/L). In Cushing disease (which is ACTH dependent), ACTH and cortisol levels increase by ≥35% and ≥ 20%, respectively. Some studies show that in Cushing disease, an increase in ACTH by ≥6 pmol/L and peak ACTH >15 pmol/L may be more accurate. In ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome and in most cases of ectopic ACTH, usually no or minor response to CRH or desmopressin is seen.

b) A high-dose dexamethasone 8-mg overnight suppression test is used to differentiate between pituitary and ectopic sources of ACTH production. Patients are instructed to take 8 mg of oral dexamethasone at bedtime (11 pm to midnight). Serum cortisol levels are measured on the day prior to and following dexamethasone administration between 8 and 9 am. Cortisol level suppression >50% is suggestive of and suppression >90% is specific for a pituitary source of abnormal ACTH production.

3) Step 3: Imaging studies. Imaging should not be performed until biochemical workup confirms Cushing syndrome and localization is completed. This will prevent the risk of finding incidentalomas.

a) Computed tomography (CT) is the first choice for the evaluation of the adrenal gland in ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome. CT helps distinguish between tumors, nodules, and hyperplasia and in most cases allows for differentiation between adrenal adenomas and carcinomas. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the adrenal gland is a good option when CT is contraindicated or unavailable.

b) MRI of the sella (Tesla-3 dynamic study with gadolinium) is the test of choice to assess for ACTH-secreting PitNETs/adenomas (50%-60% sensitivity). The most frequent findings are small PitNETs (microadenomas). If there is a PitNET sized >6 mm and the biochemical tests are concordant (see above), Cushing disease can be diagnosed.

c) Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling (BIPSS): If biochemical test results are discordant in ACTH-dependent Cushing syndrome or if a pituitary adenoma is absent on MRI or measures <6 mm, BIPSS performed by an experienced interventional neuroradiologist can be used to differentiate between pituitary and ectopic sources of ACTH.

d) The first imaging choice in identifying ectopic sources of ACTH production is CT of the chest, followed by CT of the abdomen and pelvis.

e) Molecular imaging/receptor scintigraphy with somatostatin analogues (68Ga-DOTATATE positron emission tomography [PET]-CT scan) is used in specialized settings to detect ectopic ACTH-secreting NETs.

f) Skeletal radiographs may reveal features of osteoporosis and pathologic fractures; delayed bone age is frequently seen in children and adolescents. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) may reveal features of osteopenia or osteoporosis, particularly in the lumbar spine and proximal femur.

CT and MRI of the adrenal glands reveal findings dependent on the cause of Cushing syndrome (Figure 6.1-1):

1) Autonomous adrenal cortex tumor or tumors: CT reveals a unilateral adrenal tumor with features of adenoma, atrophy of the contralateral adrenal gland, and less frequently bilateral multiple adenomas of the adrenal cortex. MRI reveals significant fat content and rapid contrast washout.

2) BMAH: CT reveals adrenal glands that are usually enlarged and often polycyclic, with large nodules; their density is typical for adenomas. MRI reveals high fat content in the adrenal glands.

3) Micronodular adrenal hyperplasia: CT and MRI usually reveal symmetric adrenal glands that are of normal or slightly increased size, with small nodules. Diagnosis is established during surgery (characteristic yellow-black color of the nodules caused by lipofuscin deposition).

Diagnostic algorithm: Figure 6.1-1. Elevated cortisol levels must be found on ≥2 separate test results.

1. Overt Cushing syndrome: Signs and symptoms of Cushing syndrome and evidence of hypercortisolism as above.

2. MACS: Cortisol suppression with 1-mg dexamethasone is impaired; cortisol is not suppressed to <50 nmol/L in the morning, while late-night salivary cortisol levels and 24-hour UFC excretion may be normal or may approach or slightly exceed the ULN. This type of Cushing syndrome is diagnosed in some incidentally detected, usually unilateral, autonomous tumors of the adrenal cortex. A small group of patients who undergo unilateral adrenalectomy for an apparently nonfunctioning adrenal tumor are retrospectively diagnosed with MACS based on postoperative central adrenal insufficiency.

Biochemical evaluation is recommended in patients with:

1) Features of Cushing syndrome.

2) Incidentally found adrenal masses.

Screening in the general population is discouraged.

Differential diagnosis of Cushing syndrome: Figure 6.1-1.

1. Physiologic nonneoplastic hypercortisolism: High serum cortisol levels resulting from abnormalities/systemic effects rather than from organic lesions in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system:

1) Depression: High serum cortisol levels and impaired dexamethasone suppression with a preserved circadian rhythm of cortisol secretion and normal serum ACTH levels.

2) Pregnancy: High blood levels of corticosteroid-binding globulin and, consequently, high cortisol levels. Placental CRH secretion increases in the third trimester of pregnancy. UFC excretion is increased and the circadian rhythm of cortisol secretion is preserved.

3) Alcohol dependence: Few patients have clinical features of Cushing syndrome (because of altered cortisol metabolism in the liver and effects of alcohol on the central nervous system). Abstinence results in the resolution of symptoms.

4) Anorexia nervosa: Elevated cortisol levels, mainly as a result of decreased renal clearance of cortisol. An increase in ACTH secretion may also occur. Impaired dexamethasone suppression caused by acquired glucocorticoid receptor resistance is present, which explains the lack of clinical features of Cushing syndrome.

5) Medications: Certain drugs (eg, carbamazepine, fenofibrate) can elevate UFC levels depending on the assay used. Estrogen can elevate total cortisol levels.

6) Morbid obesity.

7) Poorly controlled DM.

8) Obstructive sleep apnea.

9) High urine output >4 to 5 L/d.

10) Acute stress and/or severe systemic illness.

11) Chronic kidney disease.

Usually physiologic nonneoplastic hypercortisolism can be excluded clinically but if not, the following approaches can be used:

1) Dexamethasone-suppressed CRH stimulation test (3-day test): Oral dexamethasone 0.5 mg every 6 hours × 8; start at noon and administer the last dose at 6 am; then at 8 am administer CRH 1 microg/kg IV and plasma cortisol 15 minutes later; cortisol level <38 nmol/L excludes true Cushing syndrome.

2) Desmopressin stimulation test (10 microg IV): The test is described above under “Tests to identify causes of or localize Cushing syndrome”. Blood ACTH and cortisol levels rise in true Cushing disease.

3) Treat the underlying causes of physiologic nonneoplastic hypercortisolism if possible, then retest the patient with the usual tests for Cushing syndrome once adequate control is achieved.

2. Glucocorticoid resistance: A very rare syndrome of partially impaired response of the glucocorticoid receptor (a rare genetic condition). It is associated with high serum ACTH, cortisol, androgen, and aldosterone levels without symptoms of excess cortisol, but with features of aldosteronism and androgenization in women. The circadian rhythm of cortisol secretion as well as pituitary and adrenal response to CRH are preserved. The treatment is dexamethasone 1 to 1.5 mg/d to suppress ACTH secretion.

TreatmentTop

1. General measures:

1) Blood pressure management: Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists such as spironolactone can be used, particularly if hypokalemia is present.

2) DM, obesity, CAD, and hyperlipidemia are to be managed as per relevant society guidelines (see Diabetes; see Obesity; see Coronary Artery Disease; see Hyperlipidemia).

2. Prevention of complications:

1) PJP prophylaxis should be considered in prolonged/severe Cushing syndrome or other conditions posing high risk of this infection. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) (TMP 80-160 mg/d or 160 mg 3 times/wk) is the first-line treatment and should be continued 2 weeks following curative surgery or normalization of UFC.

2) VTE prophylaxis should be considered perioperatively along with active mobilization in high-risk patients.

3) Vaccines: Inactivated (eg, influenza, hepatitis, pneumococcal infections) and mRNA vaccines (eg, coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19]) are generally safe. Live attenuated vaccines (eg, measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, herpes zoster) should be avoided in immunocompromised patients or those on immunosuppressants. In patients with Cushing syndrome, a live attenuated vaccine can be given when the disease has been in remission and patients are no longer immunocompromised.

4) Osteoporosis: Excess exogenous and endogenous glucocorticoids are risk factors for low bone mass and should be incorporated into fracture risk calculators. Sufficient calcium and vitamin D intake should be encouraged. The decision whether to use antiresorptive therapy should be based on fracture risk assessment using validated tools.

Treatment of Cortisol Hypersecretion

This depends on the etiology of Cushing syndrome. Usually, surgery is the treatment of choice for most causes of Cushing syndrome, but at times medical therapy and radiotherapy may be indicated in addition to other systemic therapies depending on the etiology, clinical circumstances, and patient preference.

An overview of treatments: Table 6.1-1.

1. Surgery:

1) Adrenal etiology:

a) Adrenal cortex tumors: The treatment of choice is usually surgical resection of the adrenal tumor.Evidence 1Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the observational nature of most studies. Lacroix A, Feelders RA, Stratakis CA, Nieman LK. Cushing's syndrome. Lancet. 2015 Aug 29;386(9996):913-27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61375-1. Epub 2015 May 21. Review. PMID: 26004339. After surgical tumor resection, use hydrocortisone replacement (typical starting dose, 30-40 mg/d), as functioning of the contralateral adrenal gland is usually impaired. Over the course of the following weeks, taper the dose of hydrocortisone down to discontinuation. For the following 1 to 2 years, hydrocortisone treatment may be occasionally necessary in the event of severe stress (eg, surgery).

b) Macronodular or micronodular adrenal hyperplasia: The treatment of choice is resection of the largest adrenal gland. Administer and taper hydrocortisone as in patients after resection of a unilateral adenoma.

2) Pituitary etiology (Cushing disease): The first-line treatment is surgical resection of the pituitary tumor (commonly done through the transsphenoidal route). If the disease is refractory to pituitary tumor resection and to medical and radiation therapy (see below), bilateral adrenalectomy can be considered. A rare complication of bilateral adrenalectomy is Nelson syndrome, which is characterized by the rapid growth of the ACTH-secreting pituitary tumor. This can lead to visual disturbance by compressing the optic nerve, other pituitary hormone deficiencies, or both

3) Ectopic ACTH-secreting tumors: Treatment directed at addressing the underlying cause by primary surgical removal of the ectopic sources. Bilateral adrenalectomy can be considered as a curative choice for cortisol excess if primary surgical therapy, medical therapy, or both are not successful or in cases of severe life-threatening Cushing syndrome, where it can be lifesaving.

2. Medical therapy may be indicated to manage hypercortisolism when:

1) The patient is awaiting surgery, especially if it is delayed or the disease is severe.

2) Surgery is contraindicated.

3) Surgery is unsuccessful.

4) Medical therapy is the patient’s preference.Evidence 2Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the observational nature of most studies. Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al; Endocrine Society. Treatment of Cushing's Syndrome: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Aug;100(8):2807-31. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1818. Epub 2015 Jul 29. PMID: 26222757; PMCID: PMC4525003.

All of the above are used in specialized, often multidisciplinary, settings. Types of medical therapies:

1) Adrenal-directed therapy: There are 2 categories of adrenal-specific therapies:

a) Steroidogenesis inhibitors: Agents that decrease adrenal cortisol production (eg, ketoconazole 400-1600 mg/d in 2-3 divided doses; metyrapone 500 mg up to 6 g/d in divided doses tid-qid); osilodrostat; or uncommonly mitotane.

b) Agents that block the action of cortisol on adrenal receptors (eg, mifepristone).

2) Pituitary-directed therapy (only for pituitary Cushing disease): Second-generation somatostatin analogues (eg, pasireotide) and dopamine agonists (eg, cabergoline). The doses of these medications can be titrated to achieve optimal UFC levels.

3) Ectopic ACTH-secreting NETs: Steroidogenesis inhibitors, glucocorticoid receptor antagonists, and somatostatin analogues can be used. In selected cases, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT), local radiotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, liver-directed therapy, or other systemic therapy and/or conventional chemotherapy may be considered in a specialized setting.

3. Radiation to the pituitary gland (for pituitary Cushing disease) should be considered if surgery is contraindicated, surgical or medical treatment is unsuccessful, or in cases of tumor recurrence or Nelson syndrome. Both conventional radiation and stereotactic fractionated radiotherapy (using dynamic image–guided radiation) are offered.

Care should be taken to avoid a precipitating glucocorticoid deficit and features of impending adrenal crisis while on any therapy that can lower glucocorticoid levels. Perioperative administration of glucocorticoids is the same as perioperative management of patients with adrenal insufficiency while on medical or other therapy that lowers cortisol levels and following radiation therapy.

Treatment of Severe Cushing Syndrome

The priority is to treat the metabolic complications such as DM, hypokalemia, hypertension, heart failure, thromboembolism (including prophylaxis), psychosis, and to aggressively treat or prevent, if possible, suspected sepsis, opportunistic infections (eg, PJP prophylaxis), or perforated viscus. Rapid lowering of serum cortisol is achieved with oral metyrapone, oral ketoconazole, or a combination therapy with these 2 agents. If the patient is unable to take anything by mouth, then IV etomidate is rapidly effective in an intensive care setting. Mifepristone can be also considered in an acute cases. All these interventions require careful monitoring in a specialized setting to lower cortisol levels promptly and avoid hypercortisolism.

Pasireotide and cabergoline may be considered as part of a combination therapy in severe nonacute Cushing syndrome due to pituitary Cushing disease, understanding that they do not have a rapid onset of action. Rarely, mitotane may be considered, but it has a very slow onset and many adverse effects. If medical treatment fails, bilateral adrenalectomy needs to be performed as a lifesaving procedure.

Treatment of Mild Autonomous Cortisol Secretion

Most patients can be managed with medical treatment for related comorbidities. However, a subset of patients—such as those with a unilateral adrenal lesion, younger age, higher levels of nonsuppressed cortisol following a DST, or a high burden of associated comorbidities (eg, DM, hypertension, osteoporosis)—may benefit from adrenalectomy. The decision for adrenalectomy should be made through multidisciplinary discussions involving endocrinologists, surgeons, and radiologists.

ComplicationsTop

1. Cardiovascular: Hypertension, myocardial infarction/CAD, stroke, chronic heart failure.

2. Metabolic: Diabetes, obesity, hepatic steatosis.

3. Cutaneous: Poor wound healing, thinning.

4. Reproductive: Sexual dysfunction, infertility, androgenism.

5. Thromboembolic: Venous and arterial thromboembolism.

6. Infection: Bacterial, viral, fungal, opportunistic.

7. Neuropsychiatric: Anxiety, depression, psychosis.

8. Musculoskeletal: Osteoporosis, fractures, myopathy.

PrognosisTop

Patients with overt Cushing syndrome and MACS are at risk of long-term metabolic and cardiovascular complications. Regardless of treatment options, patients with Cushing syndrome require long-term monitoring.

1. Untreated Cushing syndrome carries a poor prognosis as a result of cardiovascular, thrombotic, neuropsychiatric, and infectious complications.

2. Resection of adrenal adenomas results in complete resolution of physical features of Cushing syndrome. The metabolic complications improve with treatment but may not resolve fully.

3. Adrenalectomy (often unilateral) in patients with micronodular and macronodular adrenal hyperplasia results in improvement/resolution of symptoms of Cushing syndrome. In patients with Carney complex, the prognosis depends on coexisting abnormalities.

4. In patients with adrenocortical carcinoma and ectopic ACTH NETs, the prognosis depends on the stage of cancer, extent of surgery, control of hypercortisolism, and response to adjuvant therapy.

5. Cushing disease (pituitary) has a high risk of recurrence and carries a risk of long-term metabolic and cardiovascular complications; close long-term monitoring is indicated.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Treatment |

Adrenal etiology | Pituitary etiology | Ectopic ACTH secretion |

|

Surgical |

– Adenoma/carcinoma: tumor resection – Macronodular or micronodular adrenal hyperplasia: resection of largest adrenal gland |

– Resection of pituitary tumor – Bilateral adrenalectomy in selected cases |

– Resection of primary tumor – Tumor debulking – Bilateral adrenalectomy in selected cases |

|

Medical |

– Steroidogenesis inhibitors (ketoconazole, metyrapone, osilodrostat, mitotane, etomidate) – Glucocorticoid receptor antagonists (mifepristone) – Chemotherapy/mitotane for adrenal carcinoma |

– Second-generation somatostatin analogues (pasireotide) – Dopamine agonists (cabergoline) – Steroidogenesis inhibitors (ketoconazole, metyrapone, osilodrostat, mitotane, etomidate) – Glucocorticoid receptor antagonists (mifepristone) |

– Steroidogenesis inhibitors (ketoconazole, metyrapone, osilodrostat, mitotane, etomidate) – Glucocorticoid receptor antagonists (mifepristone) – Somatostatin analogues (octreotide/lanreotide) – Everolimus – Tyrosine kinase inhibitors – Chemotherapy |

|

Radiotherapy |

External-beam radiation therapy for adrenal carcinoma |

Conventional versus stereotactic fractionated radiotherapy |

External-beam radiation therapy |

|

Other specialized therapies |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

– Hepatic artery embolization – Radiofrequency ablation – Peptide-receptor radiolabeled therapy |

|

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone. |

|||

Figure 6.1-1. Diagnostic algorithm in Cushing syndrome.

Figure 6.1-2. Approach to identifying the cause of endogenous Cushing syndrome.