Arbelo E, Protonotarios A, Gimeno JR, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(37):3503-3626. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad194

Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 May 3;79(17):1757-1780. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.011. Epub 2022 Apr 1. PMID: 35379504.

McDonald M, Virani S, Chan M, et al. CCS/CHFS Heart Failure Guidelines Update: Defining a New Pharmacologic Standard of Care for Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. Can J Cardiol [Internet]. 2021 Apr;37(4):531-546. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.01.017. PMID: 33827756.

Bozkurt B, Coats AJ, Tsutsui H, et al. Universal Definition and Classification of Heart Failure: A Report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2021 Mar 1;S1071-9164(21)00050-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.01.022. PMID: 33663906.

McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 21;42(36):3599-3726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021 Dec 21;42(48):4901. PMID: 34447992.

Ommen SR, Mital S, Burke MA, et al. 2020 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Dec 22;76(25):e159-e240. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.045. Epub 2020 Nov 20. PMID: 33229116.

Bozkurt B, Colvin M, Cook J, et al; American Heart Association Committee on Heart Failure and Transplantation of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Current Diagnostic and Treatment Strategies for Specific Dilated Cardiomyopathies: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016 Dec 6;134(23):e579-e646. Epub 2016 Nov 3. Erratum in: Circulation. 2016 Dec 6;134(23):e652. PMID: 27832612.

WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS, Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure: An Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2016 Sep 27;134(13):e282-93. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000435. Epub 2016 May 20. Erratum in: Circulation. 2016 Sep 27;134(13):e298. PMID: 27208050.

Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al; Authors/Task Force Members. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016 Jul 14;37(27):2129-200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. Epub 2016 May 20. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2016 Dec 30. PMID: 27206819.

Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Haghikia A, Nonhoff J, Bauersachs J. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: current management and future perspectives. Eur Heart J. 2015 May 7;36(18):1090-7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv009. Epub 2015 Jan 29. Review. PMID: 25636745; PMCID: PMC4422973.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a disease of the myocardium characterized by dilatation of the left ventricle (LV) and typically global LV systolic dysfunction. In some cases right ventricular dilatation and dysfunction may also be present.

DCM can be familial (eg, muscular dystrophies, mitochondrial cytopathies, inherited metabolic diseases) or acquired from infection (eg, viral myocarditis, Chagas disease), inflammatory causes (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), toxins (eg, alcohol, cocaine, chemotherapy drugs such as doxorubicin and trastuzumab), nutritional deficiencies (eg, thiamine or carnitine deficiency), endocrinopathies (eg, thyroid disease, acromegaly), tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, or peripartum cardiomyopathy. However, in many patients DCM is idiopathic.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

DCM most frequently causes symptoms of heart failure of varying severity (see Chronic Heart Failure). The dynamics of the disease may vary from prolonged asymptomatic periods to rapidly progressive heart failure.

DiagnosisTop

1. Chest radiography reveals an enlarged cardiac silhouette and features of pulmonary congestion.

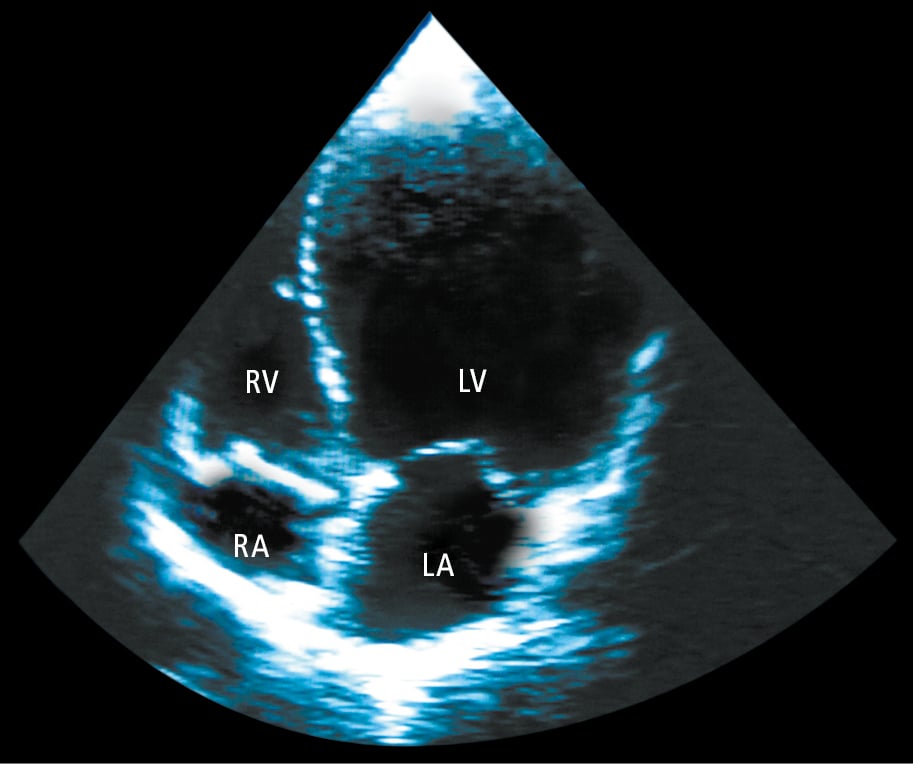

2. Echocardiography (Figure 3.6-1) usually reveals LV dilatation, eccentric hypertrophy, and systolic dysfunction. Other echocardiographic findings may include functional mitral regurgitation, abnormal LV diastolic function, left atrial dilatation, pulmonary hypertension, and right ventricular dysfunction. Contrast agents may be used to exclude an LV thrombus. Advanced techniques can allow early detection of myocardial dysfunction in specific conditions (eg, genetic carriers, recipients of cardiotoxic chemotherapy).

3. Coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) allows direct anatomical visualization of the coronary artery lumen and wall with the ability to detect obstructive coronary artery disease. It is not necessary for the diagnosis of DCM, but it serves as an important noninvasive test to exclude coronary artery disease as the cause of cardiomyopathy.

4. Cardiac catheterization is not necessary to make the diagnosis of DCM. However, coronary angiography may be performed to exclude ischemic heart disease as a cause of symptoms.

5. Endomyocardial biopsy is rarely indicated and mainly used to exclude active myocarditis in patients with rapidly progressive heart failure.

6. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an important tool for tissue characterization, evaluation of myocardial edema (this may suggest myocarditis or inflammation), and determination of the presence and extent of fibrosis, which allows the diagnosis of specific etiologies. Cardiac MRI also has prognostic value for arrhythmia and heart failure progression.

7. Genetic testing can be offered to patients with DCM as the prevalence of genetic variants is higher in familial DCM. However, causative genetic variants are also found in nonfamilial DCM cases. It is an important tool for diagnosis, prognosis, and reproductive advice. If the genetic test is positive for pathogenic variants or reports a variant of uncertain significance, a genetic counselor referral should be warranted.

DCM is diagnosed based on history, physical examination, and echocardiographic parameters of LV dilatation and dysfunction after other causes have been excluded.

Coronary artery disease leading to LV dysfunction is the most important differential diagnosis. Coronary evaluation should be considered in most adults with DCM. DCM should also be differentiated from cardiomyopathy secondary to valvular disease or prolonged hypertension.

TreatmentTop

Treatment is the same as in chronic heart failure (see Chronic Heart Failure).

Special ConsiderationsTop

1. Cardiomyopathy associated with neuromuscular disorders occurs particularly in patients with muscular dystrophy (eg, Duchenne dystrophy, Becker dystrophy, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, myotonic dystrophy) and Friedreich ataxia. Cardiac complications can include conduction abnormalities, arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death.

2. Metabolic cardiomyopathy develops in the course of certain endocrine diseases (thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, acromegaly, pheochromocytoma, adrenal insufficiency, severe obesity) or vitamin deficiency (eg, B1 deficiency causing beriberi). Treatment of the underlying condition may reverse the cardiomyopathy.

3. Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) (also see Peripartum Cardiomyopathy): The diagnosis is made when LV systolic dysfunction (LV ejection fraction [LVEF] <45%) develops at the end of pregnancy, usually in the third trimester, or within 5 months of delivery in a patient with no prior heart disease and in whom other causes of DCM have been excluded. Risk factors include mothers of a very young age or >30 years, family history of PPCM, multiple births, multiple pregnancy, history of eclampsia or preeclampsia, tobacco smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, poor nutrition, and long-term beta-blocker treatment. PPCM resolves spontaneously in ~50% of patients but it may progress to DCM. Because genetic variants have been found in 15% of women with PPCM, genetic testing should be offered in this group.

Women with peripartum cardiomyopathy have generally been excluded from clinical trials and evidence for treatment is generalized mainly from trials recruiting older patients with mixed cardiomyopathies and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Pregnant patients with heart failure should receive the same evidence-informed therapies as those with other causes bearing in mind the medications that are contraindicated during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) are contraindicated in pregnancy and may be substituted with hydralazine and nitrates for afterload reduction. Beta-blockers, preferably beta1-selective (bisoprolol or metoprolol succinate), can be used if tolerated (avoid atenolol). Mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonists are contraindicated during pregnancy. Diuretics should be used only in case of pulmonary edema or congestion.

After delivery, initiation and up-titration of standard heart failure medications is recommended until LVEF normalizes. In breastfeeding patients the preferred ACEIs are captopril, enalapril, and benazepril. Patients should be cautioned about future pregnancies if the LVEF has not recovered.

4. Alcoholic cardiomyopathy can occur because of direct cardiotoxic effects of alcohol. It may have an insidious course with atrial fibrillation often being the presenting feature, but other types of arrhythmias may also be seen. Abstinence from alcohol is recommended in alcoholic cardiomyopathy, as this may lead to resolution of early cardiomyopathy, while continued alcohol consumption worsens the prognosis. This type of cardiomyopathy is rare, so other etiologies should always be excluded before making a final diagnosis.

5. Cardiomyopathy associated with stimulant use: Cocaine, methamphetamine, ecstasy, and bath salts containing cathinone can have significant cardiotoxic effects. Acute use of cocaine may cause coronary artery spasm and acute ischemia in addition to direct myocardial damage from long-term use. Abstinence is certainly recommended. Cardioselective beta-blockers are to be avoided for treating cocaine-induced cardiomyopathy. Noncardioselective beta-blockers are preferred.

6. Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy is found in <1% of patients with chronic supraventricular tachycardia (eg, atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter with a rapid ventricular rhythm of 130-200 beats/min) or ventricular tachycardia, mainly sustained. Achieving control of arrhythmia usually leads to resolution of myocardial dysfunction within ≤3 months.

7. Chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy is caused by the toxic effect of drugs on the myocardium. The most common drugs are chemotherapeutic agents, such as anthracyclines, antibodies to the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), trastuzumab, and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Baseline and serial monitoring of LVEF with echocardiography is recommended during administration of cardiotoxic chemotherapy; discontinuation of the cardiotoxic chemotherapeutic agent may be considered if there is a drop in LVEF >5% or to <55% with concomitant heart failure, or if there is an asymptomatic drop in ejection fraction >10% or to <50%. Anthracyclines may have cardiotoxic effects months or years after administration.

8. Cardiomyopathy associated with sarcoidosis of the heart: Sarcoidosis is a noncaseating granulomatous systemic disease. Cardiac sarcoidosis may precede, occur concurrently with, or follow other organ involvement. Manifestations include ventricular arrhythmias, conduction abnormalities, valve disease, cardiomyopathy, and cor pulmonale. On imaging, sarcoid cardiomyopathy may mimic the appearance of myocardial infarction due to the presence of regional wall motion abnormalities and scar tissue. Further investigations include chest CT that should be always recommended to assess mediastinal lymphadenopathy; cardiac MRI, which is an important tool for tissue characterization and evaluation of fatty replacement; and a PET scan to determine active sarcoidosis. If sarcoidosis is diagnosed, glucocorticoid therapy is usually used.

9. Cardiomyopathy associated with HIV: Myocardial changes in HIV are caused by various factors, including HIV viremia, myocarditis, cardiac autoimmunity, and drug toxicity. Given the fact that antiretroviral therapy accelerates the process of atherosclerosis and significantly increases the risk for cardiovascular disease, it is important to exclude coronary artery disease as a possible cause of cardiomyopathy and heart failure in HIV patients. Treatment is directed at suppressing HIV viremia.

FiguresTop

Figure 3.6-1. Echocardiography (apical 4-chamber view) of a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy showing significant left ventricular (LV) dilatation. LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.