Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J 3rd, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;146(24):e334-e482. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001106

Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: Document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2014 Nov 1;35(41):2873-926. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu281. Epub 2014 Aug 29. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 1;36(41):2779. PubMed PMID: 25173340.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Aortic dissection is caused by a tear of the intima with blood penetrating into the media. This results in the separation of the intima from the media and adventitia and creates a false lumen of the aorta.

Aortic dissections may be divided according to the Stanford classification into type A and type B. Type A aortic dissections refer to dissections involving the ascending aorta, aortic arch, or both regardless of the site of origin (70%). These may extend down into the descending thoracic or thoracoabdominal aorta. Type B aortic dissections occur distal to the left subclavian or even innominate artery and involve the descending thoracic or thoracoabdominal aorta.

The DeBakey classification for aortic dissections is also commonly used. DeBakey type I dissections involve the ascending aorta, arch, and descending thoracic aorta and may extend into the abdominal aorta. DeBakey type II dissections are limited to the ascending aorta. DeBakey type III dissections (like Stanford type B) arise distal to the left subclavian artery.

Risk factors for aortic dissection include hypertension (usually poorly controlled), bicuspid aortic valve and coarctation of the aorta (including patients after surgical correction of these malformations), history of aortic disease (eg, aortic aneurysm) or aortic valve disease, positive family history of aortic disease, congenital connective tissue diseases (Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), cystic medial degeneration (in patients >50 years of age), aortitis, trauma (traffic accidents, iatrogenic), hemodynamic and hormonal factors during pregnancy (50% of aortic dissections in patients aged <40 years occur in pregnant women), Turner syndrome, cardiovascular surgery, professional weightlifting, tobacco smoking, and IV use of cocaine or amphetamines.

Clinical FeaturesTop

Aortic dissection usually manifests as severe chest pain (features: see Table 1.4-1) that often leads to syncope and does not respond to sublingual or oral nitrates. It may be accompanied by symptoms of shock, neurologic symptoms (cerebral ischemia, less commonly paraplegia, upper or lower limb ischemic neuropathy, Horner syndrome, hoarseness), myocardial infarction (if dissection involves the coronary artery ostia), heart failure (in the case of severe aortic regurgitation) and cardiac tamponade, pleural effusion, acute kidney injury (involvement of the ostia of renal arteries), abdominal pain (involvement of the ostia of the celiac trunk or mesenteric arteries), features of acute limb ischemia, and limb paralysis due to spinal cord ischemia. Physical findings may include high blood pressure (BP) (50% of patients) or hypotension, diastolic murmur audible over the aortic valve caused by severe aortic regurgitation, and pulse deficit in one extremity (in ~30% of patients with dissection of the ascending aorta, aortic arch, or both). The presenting feature may also be syncope without pain and neurologic symptoms.

Symptoms indicative of the severity of the patient’s condition: Very severe pain, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, cyanosis, shock.

DiagnosisTop

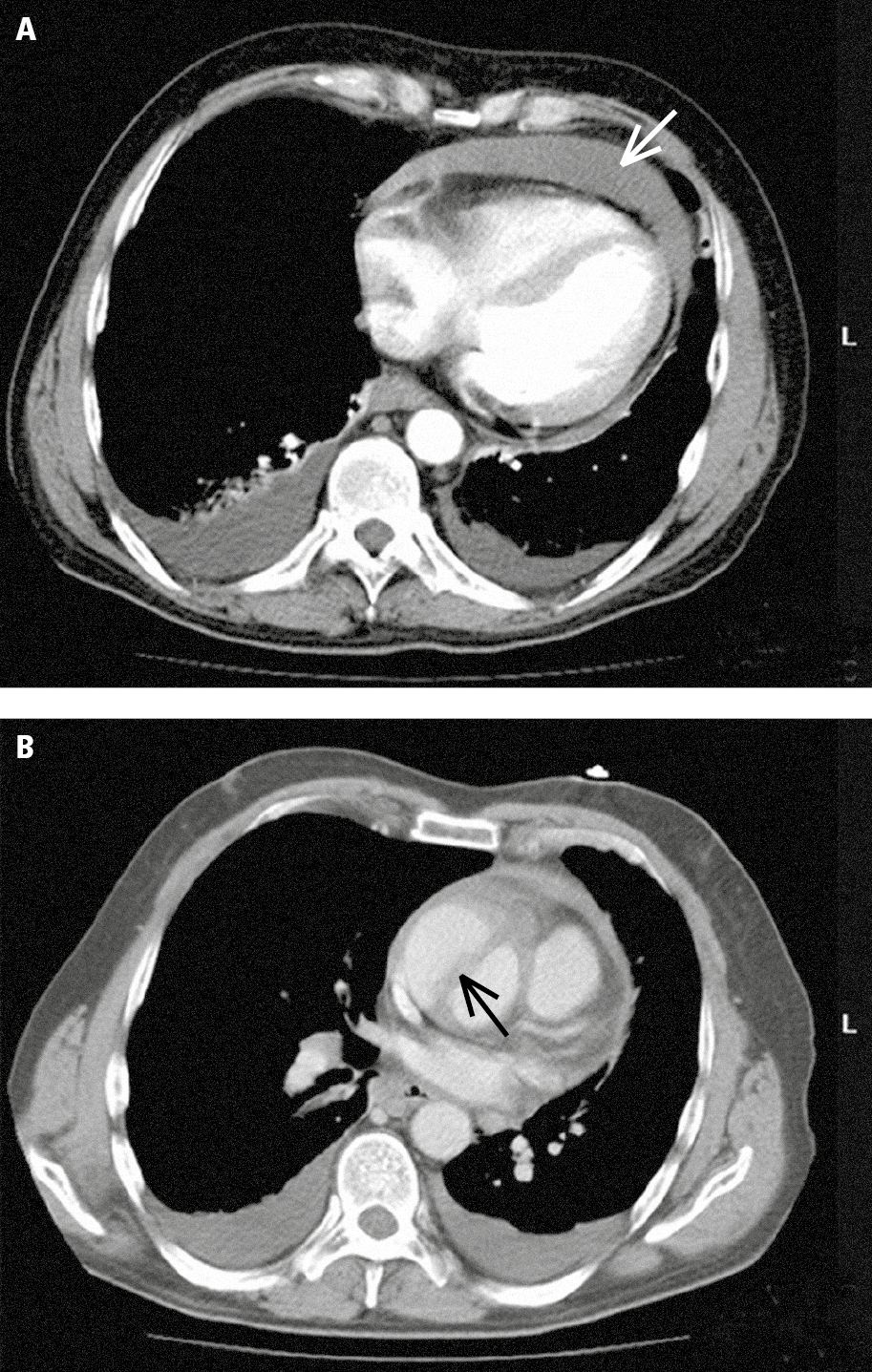

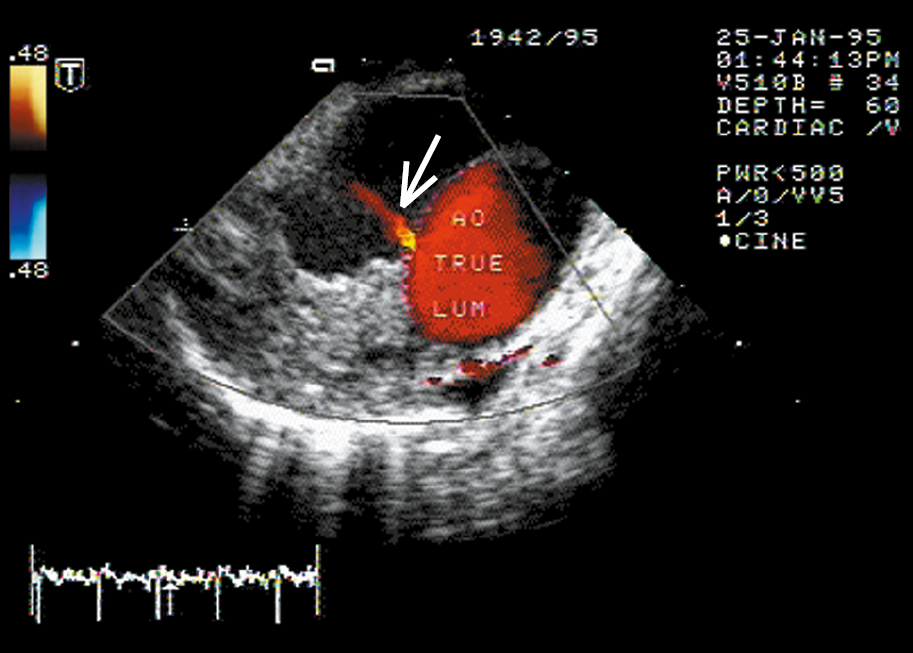

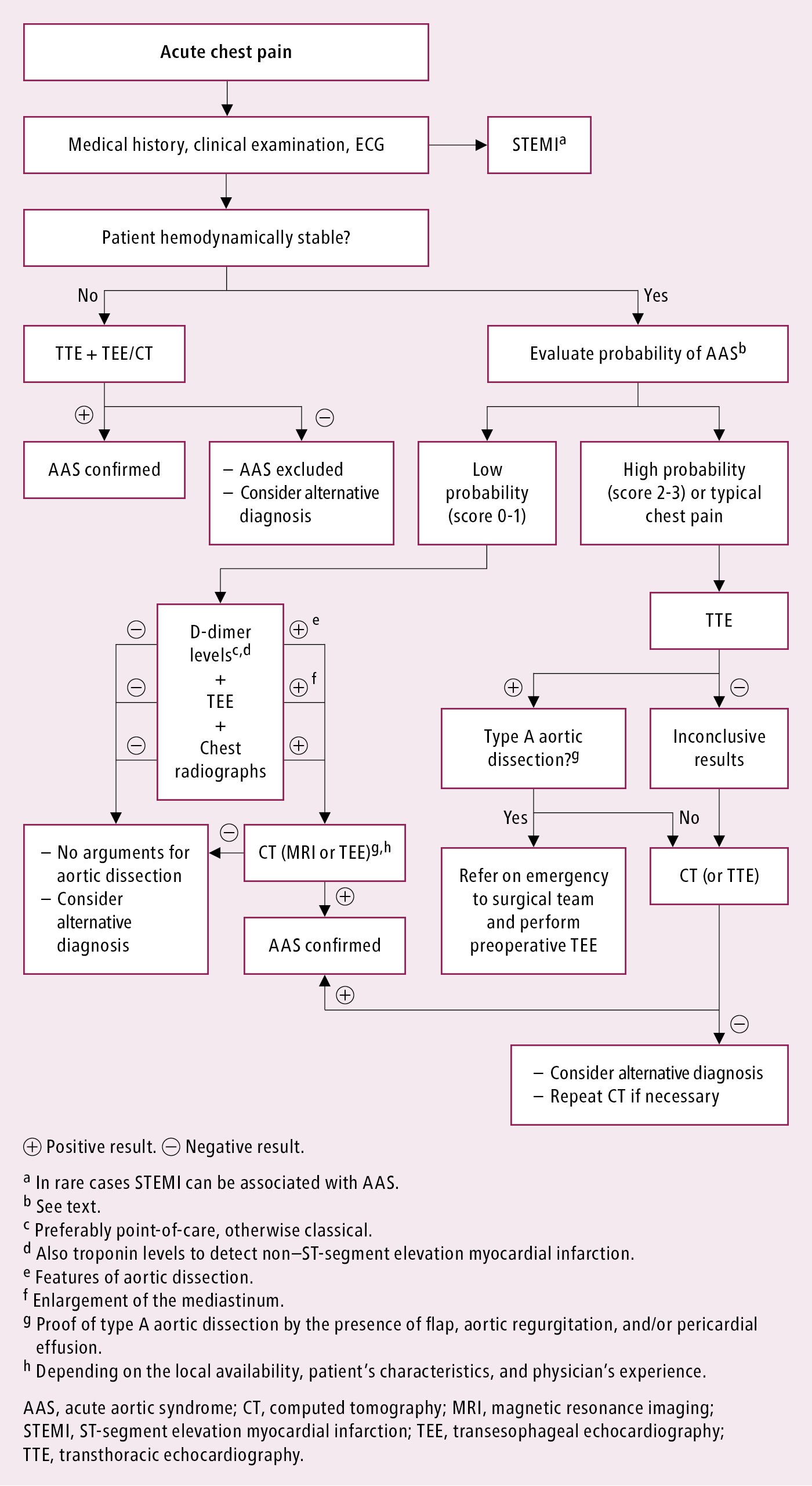

Diagnosis should be established immediately (do not prolong diagnostics in a center not capable of providing invasive treatment). Assess the clinical risk of dissection (Table 3.19-2). Aortic dissection should be differentiated from other causes of chest pain. Diagnosis must be confirmed with an imaging study (preferably computed tomography angiography [CTA] [Figure 3.19-1]; in unstable patients transesophageal echocardiography [TEE] [Figure 3.19-2] is equivalent). Chest radiography may reveal enlargement of the cardiac silhouette, rarely of the upper mediastinum; in the case of rupture into the pleural cavity, radiography reveals pleural effusion. Normal results of imaging studies do not exclude aortic dissection. In case of sustained suspicion of aortic dissection despite normal baseline imaging study results, repeated imaging study using CTA or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is recommended. Proposed diagnostic algorithm: Figure 3.19-3.

TreatmentTop

Secure peripheral venous access and—if this does not delay the diagnostic process—central venous access. Monitor urine output, heart rate, BP, electrocardiography (ECG), and arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2); continue monitoring while transporting the patient to a specialist center.

1. Medical treatment: Medical treatment is used in the initial treatment and stabilization of patients with all types of aortic dissections and may be the sole treatment for uncomplicated type B dissections. (All type A and complicated type B dissections should be considered for immediate surgery [type A] or endovascular repair [type B].)

1) Administer IV morphine for pain control.

2) Quickly lower BP (systolic BP to 100-120 mm Hg after excluding severe aortic regurgitation):

a) Administer an IV beta-blocker, such as propranolol 1 mg every 3 to 5 minutes until the target BP is achieved (up to a maximum of 10 mg) then every 4 to 6 hours; or esmolol (dosage: see Table 3.9-2). In patients with asthma or severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, replace beta-blockers with calcium channel blockers (or short-acting esmolol).

b) In some patients it may be necessary to add IV nitroglycerin, and if this is ineffective, you may use IV sodium nitroprusside (agents and dosage: see Table 3.9-2). In case of refractory hypertension, you may add enalapril (start from 0.625-1.25 mg IV every 6 hours [up to a maximum of 5 mg]).

2. Invasive treatment: Urgent surgical intervention is the treatment of choice in the majority of patients with type A dissection (perform CT only in hemodynamically stable patients when the study does not delay transfer to a cardiac surgery center).

In the case of type B (or DeBakey III) dissections, intervention beyond medical management is typically required for all complicated type B dissections and can be considered for uncomplicated type B dissections with high-risk anatomic or clinical features.

Complicated type B dissections are those defined as ≥1 of the following: end-organ malperfusion (bowel, renal, spinal cord, lower extremity ischemia), rapid aortic expansion, refractory chest or back pain, uncontrolled hypertension despite adequate pharmacotherapy, signs of rupture (hemothorax, expanding periaortic or mediastinal hematoma). Treatment options for complicated type B dissections include endovascular stenting of the aortic entry tear and fenestration or stenting of branch vessels to restore perfusion in any ischemic organs. Open surgical repair of complicated type B dissections is increasingly rare and generally happens when endovascular repair is unavailable or not feasible.

There is ongoing debate and study into the merits of endovascular treatment of uncomplicated type B dissections with high-risk anatomic or clinical features with the goal of reducing long-term complications, such as late aneurysmal change, and improving long-term survival. High-risk anatomic or imaging findings include a large initial maximal aortic diameter (>40 mm) and/or significant increase (>5 mm) in diameter on serial imaging studies, a false-lumen diameter >20 to 22 mm, an entry tear >10 mm, an entry tear on the lesser curve of the aorta, bloody pleural effusion, and imaging-only (but not clinical) malperfusion. High-risk clinical features include refractory hypertension (after treatment with multiple agents), refractory pain (persisting after maximal drug doses), and need for readmission. Decisions about endovascular treatment for patients with uncomplicated dissections but high-risk features will need to be made after careful consideration and on an individual basis.

ComplicationsTop

Complications, as mentioned above, can include aortic regurgitation, tamponade and coronary ischemia (in patients with ascending aortic dissection), ischemia of the extremities and internal organs, stroke, paraplegia, intestinal ischemia, and aortic rupture.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Conditions Marfan syndrome (or other connective tissue disease) Family history of aortic disease Known aortic valve disease Known thoracic aortic aneurysm Previous aortic manipulation (including cardiac surgery) |

|

Pain features Chest, back, or abdominal pain characterized by any of: – Abrupt onset – Severe intensity – Ripping or tearing |

|

Examination features Evidence of perfusion deficit: – Pulse deficit – Systolic blood pressure difference in upper limbs – Focal neurologic deficit (in conjunction with pain) Aortic diastolic murmur (new and with pain) Hypotension or shock |

|

The presence of features from one of the groups amounts to 1 point; from 2 groups, 2 points; and from 3 groups, 3 points. The higher the score on a scale from 0 to 3, the higher the risk of acute aortic syndrome before additional diagnostic tests are performed. |

|

Based on Circulation. 2010 Apr 6;121(13):e266-369. |

Figure 3.19-1. Multislice computed tomography (CT) in a patient with acute ascending aortic dissection: A, pericardial effusion (white arrow) and pleural effusion (red arrows); B, dissected ascending aorta (the arrow marks the dissection flap). Figure courtesy of Dr Jerzy Walecki.

Figure 3.19-2. Descending aortic dissection. Transesophageal color Doppler ultrasonography reveals flow from the true lumen through the intimal tear (arrow). Figure courtesy of Dr Marek Krzanowski.

Figure 3.19-3. Diagnosis of suspected acute aortic syndrome. Based on Eur Heart J. 2014;35(41):2873-926.