Maz M, Chung SA, Abril A, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation guideline for the management of giant cell arteritis and Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Aug;73(8):1349-1365. doi: 10.1002/art.41774. Epub 2021 Jul 8. PMID: 34235884.

Arend WP, Michel BA, Bloch DA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990 Aug;33(8):1129-34. PubMed PMID: 1975175.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Takayasu arteritis (TA) is a granulomatous vasculitis of large and medium vessels of unknown etiology that affects mostly the aorta and its branches. Less frequently it may involve other arteries, such as the pulmonary arteries.

TA typically causes numerous segmental stenoses of the aortic branches. Thrombi may form in the stenotic segments and sometimes cause peripheral thromboembolism. Aneurysms usually occur distal to the stenosis. TA rarely leads to aortic dissection or rupture.

In general terms, large-vessel vasculitis occurring in patients aged >50 years is usually diagnosed as or takes the clinical form of giant cell arteritis (GCA)/temporal arteritis. In younger people (<50 years and more so <40 years) the clinical presentation and diagnosis is usually that of TA.

Clinical FeaturesTop

Among patients with TA, 80% to 90% are women. The age of onset is typically 10 to 40 years of age. The prevalence is highest in people of Asian descent.

1. Systemic manifestations: Early manifestations usually include influenza-like or rheumatic-like symptoms, such as low-grade fever, fatigue, myalgia, and arthralgia. Acute symptoms usually resolve spontaneously but may occur throughout the disease course.

2. Vascular manifestations: Patients with chronic disease develop symptoms of stenosis and arterial occlusion. Typical findings include weak or asymmetric pulses in the upper extremities (“pulseless disease”) and bruits in the aorta and its main branches. With inflammation of the vasculature, pain and tenderness over the affected vessels may occur.

1) Aortic disease: The presenting manifestation may be an incidentally detected large thoracic aortic aneurysm. Patients may have audible bruits over stenoses within the aorta and a diastolic murmur of aortic regurgitation (an adverse prognostic factor). Heart failure from aortic insufficiency may occur.

2) Subclavian arteries: Stenosis or occlusion of a subclavian artery may lead to subclavian artery bruits, upper extremity claudication, and subclavian steal syndrome (reversal of ipsilateral vertebral artery flow leading to symptoms of vertebrobasilar ischemia). In patients with stenotic or occluded subclavian arteries, traditional blood pressure measurements are unreliable. A systolic blood pressure differential >10 mm Hg between the arms is abnormal. Systolic blood pressure should be measured on lower extremities with a Doppler device used for ankle-brachial index (ABI) measurements.

3) Carotid and vertebral arteries: Manifestations depend on the location of stenosis and include dizziness, syncope, headache, visual disturbances, transient ischemic attacks, stroke, seizures, and claudication of the jaw.

4) Renal arteries: Patients commonly develop renal artery stenosis and resultant hypertension.

5) Gastrointestinal arteries: Abdominal pain, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal bleeding can occur from celiac and mesenteric artery involvement.

6) Pulmonary arteries: Dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain can be evidence of pulmonary artery involvement.

7) Coronary arteries: Manifestations of myocardial ischemia may occur from coronary artery involvement or ostial narrowing.

DiagnosisTop

1. Blood tests: Laboratory findings in patients with TA are not specific and reflect the underlying inflammation. A normochromic normocytic anemia is common. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) can reflect disease activity, but values within reference ranges alone are not sensitive enough to exclude active disease. Other laboratory abnormalities may include an elevated fibrinogen concentration, hypoalbuminemia, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia.

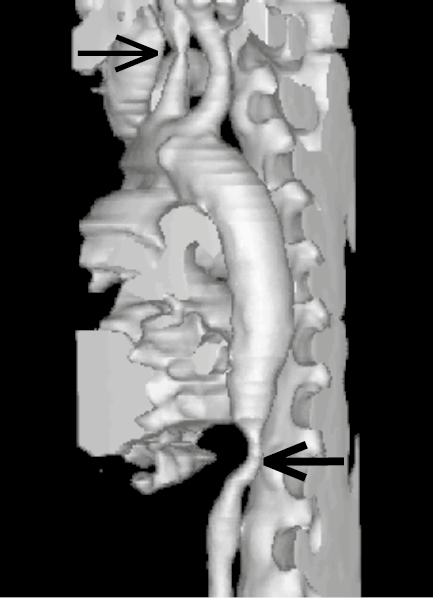

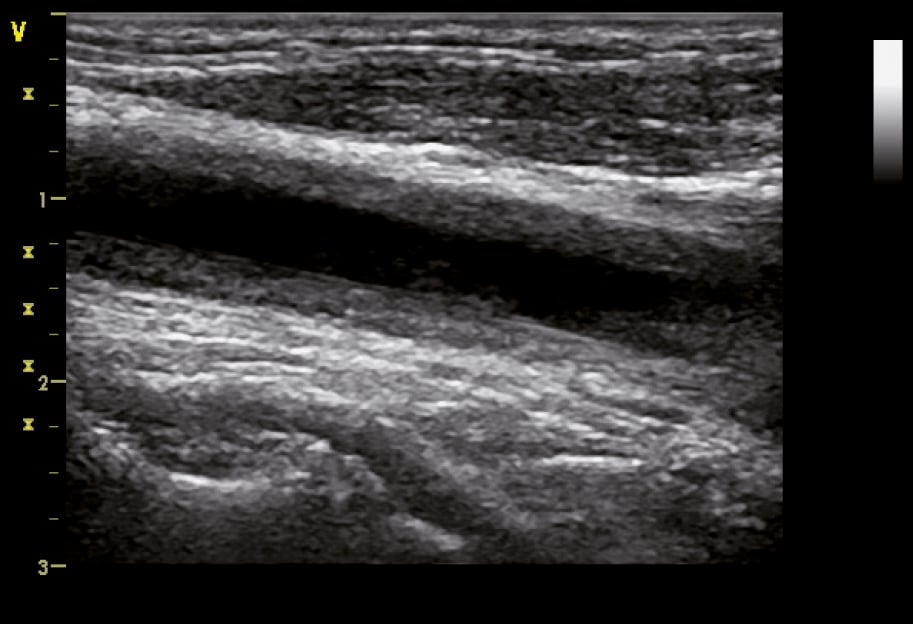

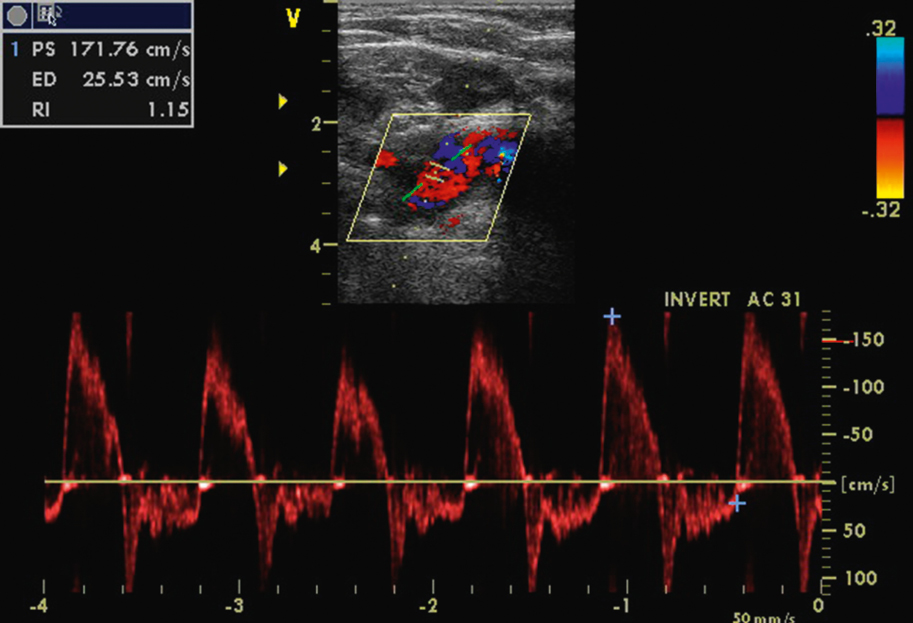

2. Imaging studies: Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), computed tomography angiography (CTA) (Figure 18.25-1), and angiography of the affected vessels demonstrate smooth luminal narrowing and possibly occlusion. CTA and MRA also have the added benefit of demonstrating wall thickening of the affected vessels. Positron emission tomography (PET) is being investigated as an imaging technique to monitor disease activity. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is useful to assess for proximal aortic abnormalities and concomitant aortic insufficiency. Ultrasonography of other affected vessels (Figure 18.25-2, Figure 18.25-3) can also be useful if available.

The American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for TA were designed to differentiate TA from other forms of vasculitis but are useful to help guide diagnosis. The classification requires that ≥3 of the following 6 criteria are met:

1) Disease onset at age ≤40 years (note that many experts now use age <50 years).

2) Claudication of any extremity (abnormal fatigue or discomfort with use, especially in the case of the upper extremities).

3) Weak or absent pulse in a brachial artery.

4) A systolic blood pressure differential between the arms ≥10 mm Hg.

5) Bruit over the subclavian artery or abdominal aorta.

6) Angiographic abnormalities not attributable to other causes, including stenosis or occlusion of the aorta, aortic branches, or proximal segments of the limb arteries.

GCA, aortic arch atherosclerosis, upper thoracic outlet syndrome, fibromuscular dysplasia of arteries, Behçet disease, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and ergotism.

Treatment Top

1. Glucocorticoids: Optimal dosing and duration of glucocorticoid therapy in TA are unknown. Initial treatment for active disease is suggested with high-dose glucocorticoids (oral prednisone 1 mg/kg daily) for 2 to 4 weeks followed by a taper to 20 mg by 3 months. If inflammatory markers normalize, constitutional symptoms improve, and clinical findings do not progress, the dose can be tapered down at a maximum rate of 10% of the dose per week. Most patients will remain on low-dose glucocorticoids to prevent relapse.Evidence 1Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to collected data coming from observational and retrospective studies with small numbers of patients. Because glucocorticoids are consistently used as initial treatment in these studies, comparisons with other potential first-line therapies are not available. Mutoh T, Shirai T, Fujii H, Ishii T, Harigae H. Insufficient Use of Corticosteroids without Immunosuppressants Results in Higher Relapse Rates in Takayasu Arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2020 Feb;47(2):255-263. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.181219. Epub 2019 May 15. PMID: 31092708.

2. Glucocorticoid-sparing agents are started in conjunction with glucocorticoids, typically methotrexate or azathioprine.Evidence 2Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to collected data coming from observational and retrospective studies with small numbers of patients. Because glucocorticoids are consistently used as initial treatment in these studies, comparisons with other potential first-line therapies are not available. Mutoh T, Shirai T, Fujii H, Ishii T, Harigae H. Insufficient Use of Corticosteroids without Immunosuppressants Results in Higher Relapse Rates in Takayasu Arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2020 Feb;47(2):255-263. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.181219. Epub 2019 May 15. PMID: 31092708. Hoffman GS, Merkel PA, Brasington RD, Lenschow DJ, Liang P. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with difficult to treat Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Jul;50(7):2296-304. doi: 10.1002/art.20300. PMID: 15248230.

3. Biologic agents: In patients with disease refractory to glucocorticoid-sparing agents or in those who relapse with attempts to discontinue glucocorticoids, addition of an anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha agent is suggested. Considerations include tocilizumab (interleukin-6 [IL-6] inhibition) or ustekinumab (IL-12/23 inhibition).Evidence 3Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered because studies are limited to one double-blind study, observational studies and case reports. Nakaoka Y, Isobe M, Takei S, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with refractory Takayasu arteritis: results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial in Japan (the TAKT study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Mar;77(3):348-354. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211878. Epub 2017 Nov 30. PMID: 29191819; PMCID: PMC5867398. Mekinian A, Resche-Rigon M, Comarmond C, et al; French Takayasu network. Efficacy of tocilizumab in Takayasu arteritis: Multicenter retrospective study of 46 patients. J Autoimmun. 2018 Jul;91:55-60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.04.002. Epub 2018 Apr 17. PMID: 29678346. Saur SJ, Horger M, Henes J. Successful treatment with the IL12/IL23 antagonist ustekinumab in a patient with refractory Takayasu arteritis. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2021 Jan 20;5(1):rkaa082. doi: 10.1093/rap/rkaa082. PMID: 33604503; PMCID: PMC7878844.

Invasive treatment (surgical or endovascular) depends on the clinical features of organ ischemia. Restenosis following vascular interventions is common and can occur in as many as 50% of patients after 2 years.Evidence 4Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know the true rate of restenosis following surgical intervention for stenosis in Takayasu arteritis). Quality of Evidence lowered because studies are limited to chart reviews with large heterogeneity between the revascularization procedures performed. Park MC, Lee SW, Park YB, Lee SK, Choi D, Shim WH. Post-interventional immunosuppressive treatment and vascular restenosis in Takayasu's arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006 May;45(5):600-5. Epub 2005 Dec 13. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kei245. PubMed PMID: 16352637. Liang P, Tan-Ong M, Hoffman GS. Takayasu's arteritis: vascular interventions and outcomes. J Rheumatol. 2004 Jan;31(1):102-6. PubMed PMID: 14705227. Surgery may be required in patients with aortic regurgitation.

FiguresTop

Figure 18.25-1. Takayasu arteritis: computed tomography (CT), 3D reconstruction. Stenosis of the left common carotid artery (thin arrow) and of the abdominal aorta (thick arrow). Figure courtesy of Dr Leszek Masłowski.

Figure 18.25-2. B-mode ultrasonography of the common carotid artery in a 32-year-old woman with Takayasu arteritis showing homogenous hypoechoic wall thickening (wall echogenicity increases in late disease) clearly separated from the arterial lumen, which is typical of vasculitis. Figure courtesy of Dr Leszek Masłowski.

Figure 18.25-3. Abnormal spectrum of blood flow velocity in the subclavian artery in a woman with Takayasu arteritis and severe aortic regurgitation. Note the long retrograde flow phase (absent in patients without regurgitation). Figure courtesy of Dr Marek Krzanowski.