Gladstone DJ, Lindsay MP, Douketis J, et al. Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Secondary Prevention of Stroke Update 2020. Can J Neurol Sci. 2021 Jun 18:1-23. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2021.127. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34140063.

Bonati LH, Kakkos S, Berkefeld J, et al. European Stroke Organisation guideline on endarterectomy and stenting for carotid artery stenosis. Eur Stroke J. 2021 Jun;6(2):I. doi: 10.1177/23969873211026990. Epub 2021 Jun 18. PMID: 34414303; PMCID: PMC8370086.

Fonseca AC, Merwick Á, Dennis M, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on management of transient ischaemic attack. Eur Stroke J. 2021 Jun;6(2):CLXIII-CLXXXVI. doi: 10.1177/2396987321992905. Epub 2021 Mar 16. PMID: 34414299; PMCID: PMC8370080.

Etiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical FeaturesTop

Atherosclerosis is the cause of >90% of all cases of stenosis or occlusion of the carotid arteries and most cases of stenosis of the vertebral arteries; rare causes include postradiotherapy stenosis, systemic vasculitis, spontaneous or traumatic artery dissection, and fibromuscular dysplasia. Carotid or vertebral artery stenosis may be symptomatic or asymptomatic.

1. Symptomatic carotid artery stenosis is defined as a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke that has occurred within the prior 6 months in the vascular territory of the stenotic carotid artery. Neurologic symptoms may include:

1) Motor or sensory disturbances contralateral to the stenosis.

2) Speech disorder in the case of stenosis of the artery supplying the dominant hemisphere.

3) Inattention or neglect in the case of stenosis of the artery supplying the nondominant hemisphere.

4) Monocular visual disturbances ipsilateral to the stenosis (amaurosis fugax).

2. Symptomatic vertebral artery stenosis is defined as a TIA or stroke that has occurred in the vascular territory of the vertebrobasilar or posterior cerebral arteries. Neurologic symptoms may include:

1) Motor or sensory disturbances with cranial nerve involvement.

2) Crossed motor or sensory disturbances (face ipsilateral, arm and leg contralateral).

3) Gait ataxia especially if associated with limb ataxia or the symptoms and signs listed above.

DiagnosisTop

Auscultation for a carotid bruit is not sufficient to confirm or exclude carotid stenosis and should not be used for this purpose.Evidence 1Strong recommendation (downsides clearly outweigh benefits; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision and indirectness. Ratchford EV, Jin Z, Di Tullio MR, et al. Carotid bruit for detection of hemodynamically significant carotid stenosis: the Northern Manhattan Study. Neurol Res. 2009 Sep;31(7):748-52. doi: 10.1179/174313209X382458. Epub 2009 Jan 7. PubMed PMID: 19133168; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2727568.

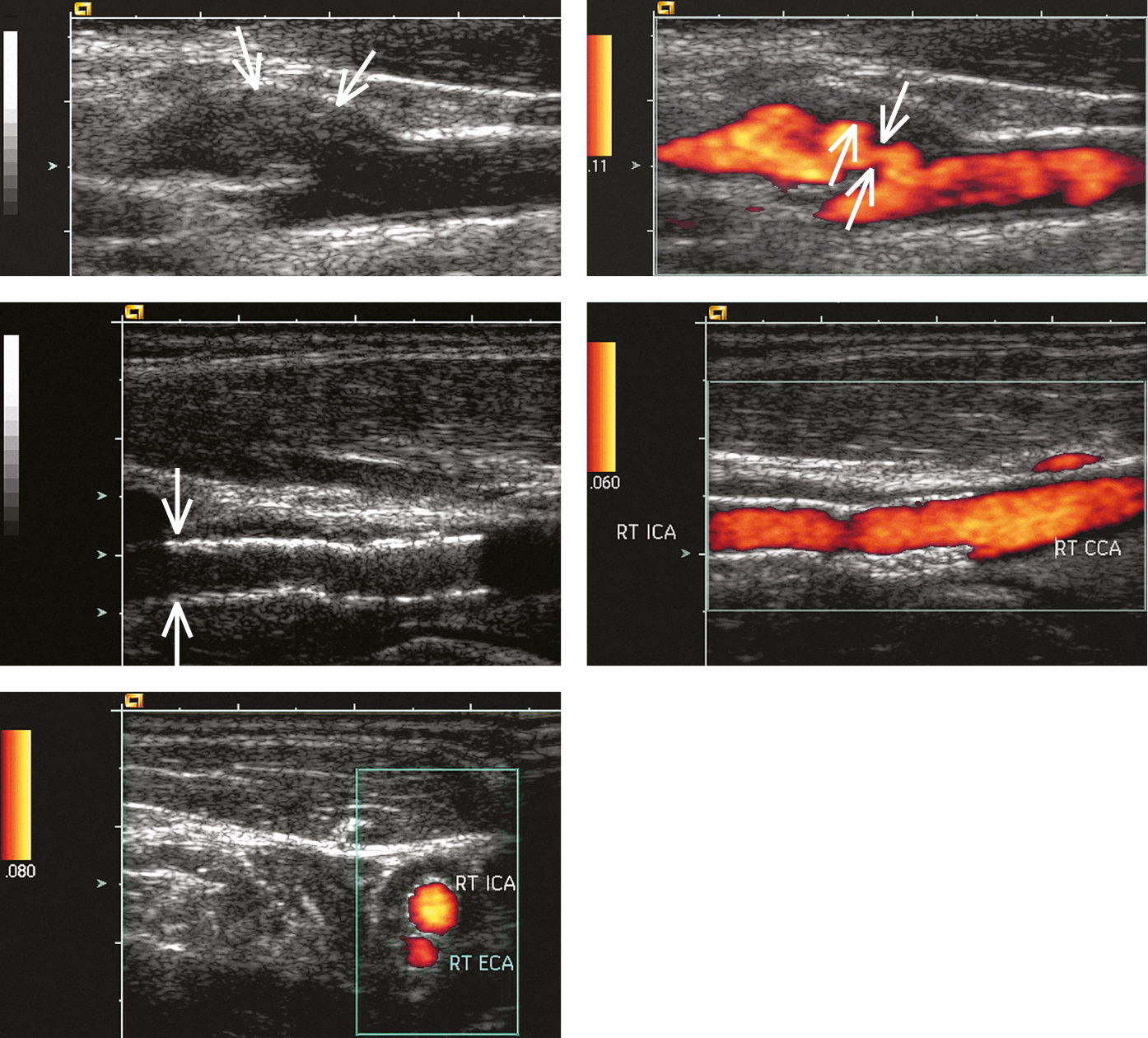

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain should be done to identify cerebral infarction and to exclude hemorrhage. MRI is more sensitive for detecting ischemia than CT, especially in the posterior fossa. Color Doppler ultrasonography (Figure 3.19-1) can accurately locate the atherosclerotic plaque, assess its morphology, and determine the severity of stenosis in carotid artery disease but not vertebral disease or intracranial disease. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or computed tomography angiography (CTA) should be done to confirm the degree of stenosis and assess for vertebral or intracranial stenosis.Evidence 2Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision. Chappell FM, Wardlaw JM, Young GR, et al. Carotid artery stenosis: accuracy of noninvasive tests--individual patient data meta-analysis. Radiology. 2009 May;251(2):493-502. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2512080284. Epub 2009 Mar 10. PubMed PMID: 19276319. Because of the risk of complications, arteriography is reserved for situations when the severity or cause of stenosis cannot be assessed using other modalities.

TreatmentTop

Recommended treatment of carotid artery stenosis: Table 3.19-3.

1. Management of risk factors for atherosclerosis: see Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases. Use a statin in all patients, including those with asymptomatic stenosis. Make attempts to control diabetes mellitus. Smoking should be strongly discouraged.

2. Antiplatelet treatment: In asymptomatic patients the risks and benefits of long-term use of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) should be considered based on lack of efficacy for primary prevention in high-risk populations.Evidence 3Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, et al; ASPREE Investigator Group. Effect of Aspirin on Cardiovascular Events and Bleeding in the Healthy Elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18;379(16):1509-1518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805819. Epub 2018 Sep 16. PMID: 30221597; PMCID: PMC6289056. ASCEND Study Collaborative Group, Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, et al. Effects of Aspirin for Primary Prevention in Persons with Diabetes Mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18;379(16):1529-1539. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804988. Epub 2018 Aug 26. PMID: 30146931. Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, et al; ARRIVE Executive Committee. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018 Sep 22;392(10152):1036-1046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31924-X. Epub 2018 Aug 26. PMID: 30158069; PMCID: PMC7255888. All symptomatic patients should receive lifelong treatment with ASA 75 to 325 mg/d. If ASA is contraindicated, use clopidogrel 75 mg/d. For symptomatic intracranial disease, administer 2 antiplatelet agents for 90 days.Evidence 4Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirect comparison. Derdeyn CP, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, et al; Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis Trial Investigators. Aggressive medical treatment with or without stenting in high-risk patients with intracranial artery stenosis (SAMMPRIS): the final results of a randomised trial. Lancet. 2014 Jan 25;383(9914):333-41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62038-3. Epub 2013 Oct 26. PubMed PMID: 24168957; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3971471. Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, et al; Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Trial Investigators. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 31;352(13):1305-16. PubMed PMID: 15800226. Antiplatelet treatment is recommended over anticoagulation in patients with symptomatic intracranial disease.Evidence 5Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirect comparison. Derdeyn CP, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, et al; Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis Trial Investigators. Aggressive medical treatment with or without stenting in high-risk patients with intracranial artery stenosis (SAMMPRIS): the final results of a randomised trial. Lancet. 2014 Jan 25;383(9914):333-41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62038-3. Epub 2013 Oct 26. PubMed PMID: 24168957; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3971471.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, et al; Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Trial Investigators. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 31;352(13):1305-16. PubMed PMID: 15800226. Add clopidogrel 300 to 600 mg as a loading dose followed by 75 mg/d to ASA 50 to 325 mg for 30 days in patients with a recent TIA or minor stroke and extracranial carotid diseaseEvidence 6Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al; CHANCE Investigators. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 4;369(1):11-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340. Epub 2013 Jun 26. PubMed PMID: 23803136. Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al; Clinical Research Collaboration, Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials Network, and the POINT Investigators. Clopidogrel and Aspirin in Acute Ischemic Stroke and High-Risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 19;379(3):215-225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800410. Epub 2018 May 16. PubMed PMID: 29766750; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6193486. Rahman H, Khan SU, Nasir F, Hammad T, Meyer MA, Kaluski E. Optimal Duration of Aspirin Plus Clopidogrel After Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. Stroke. 2019 Apr;50(4):947-953. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023978. PubMed PMID: 30852971. (see Stroke). After endovascular angioplasty and stenting, our practice—acknowledging the lack of high-quality evidence to determine the duration of treatments—is to administer 2 antiplatelet agents for at least 30 days and ASA indefinitely.

1. Carotid artery stenosis: Surgical removal of the atherosclerotic plaques that cause the stenosis (endarterectomy) or endovascular angioplasty with stent implantation. Treatment should be started as soon as possible after the symptomatic event to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke.Evidence 7Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias (subgroup analysis). Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP, Barnett HJ; Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists Collaboration. Endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis in relation to clinical subgroups and timing of surgery. Lancet. 2004 Mar 20;363(9413):915-24. PubMed PMID: 15043958. Endarterectomy is preferred over carotid artery stenting in older patients (eg, >75 years) to reduce the risk of periprocedural stroke.Evidence 8Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Antoniou GA, Georgiadis GS, Georgakarakos EI, et al. Meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis of outcomes of carotid endarterectomy and stenting in the elderly. JAMA Surg. 2013 Dec;148(12):1140-52. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4135. Review. PubMed PMID: 24154858. Either treatment could be considered in younger patients. Endovascular treatment is, however, the treatment of choice for high-risk patients with any of the followingEvidence 9Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Yadav JS, Wholey MH, Kuntz RE, et al; Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy Investigators. Protected carotid-artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2004 Oct 7;351(15):1493-501. PubMed PMID: 15470212.:

1) Stenosis eligible for invasive treatment in a patient with general contraindications to surgery.

2) Severe cardiac or pulmonary disease.

3) Contralateral carotid occlusion.

4) Stenosis that is inaccessible to the surgeon for anatomical reasons.

5) Restenosis of the internal carotid artery after endarterectomy.

6) Postradiotherapy stenosis.

Medical management is usually preferred over a surgical or endovascular intervention for patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis, although surgery or stenting could be considered on an individual basis if the procedural risk is low and the patient’s life expectancy is >5 years.Evidence 10Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness (relative lack of contemporary studies of the subject). Hart RG, Ng KH. Stroke prevention in asymptomatic carotid artery disease: revascularization of carotid stenosis is not the solution. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2015;125(5):363-9. Epub 2015 Apr 17. PubMed PMID: 25883075. Chambers BR, Donnan GA. Carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Oct 19;(4):CD001923. Review. PubMed PMID: 16235289. Halliday A, Bulbulia R, Bonati LH, et al; ACST-2 Collaborative Group. Second asymptomatic carotid surgery trial (ACST-2): a randomised comparison of carotid artery stenting versus carotid endarterectomy. Lancet. 2021 Sep 18;398(10305):1065-1073. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01910-3. Epub 2021 Aug 29. PMID: 34469763; PMCID: PMC8473558.

2. Vertebral or basilar artery stenosis: In patients with symptomatic vertebral or basilar artery stenosis, dual antiplatelet treatment for 90 days after a neurologic event and single antiplatelet treatment indefinitely is recommended over invasive treatment.Evidence 11Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Derdeyn CP, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, et al; Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis Trial Investigators. Aggressive medical treatment with or without stenting in high-risk patients with intracranial artery stenosis (SAMMPRIS): the final results of a randomised trial. Lancet. 2014 Jan 25;383(9914):333-41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62038-3. Epub 2013 Oct 26. PubMed PMID: 24168957; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3971471. Antiplatelet treatment is recommended over anticoagulation in patients with symptomatic vertebral or basilar stenosis.Evidence 12Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, et al; Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Trial Investigators. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 31;352(13):1305-16. PubMed PMID: 15800226.

Tables and FiguresTop

Figure 3.19-1. Carotid ultrasonography: A, B-mode longitudinal image of the carotid sinus and proximal segment of the right internal carotid artery (ICA). A poorly demarcated parietal lesion is seen in the proximal ICA segment, most likely atherosclerotic plaque (arrows); B, power Doppler ultrasonography shows arterial stenosis and deep ulceration (thick arrow) of the stenotic lesion (thin arrows; arterial lumen marked with color); C, D, a stent graft visible at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery, wide arterial lumen; E, stent grafts seen on the transverse image right above the common carotid artery bifurcation into the right ICA and right external carotid artery (ECA), normal arterial lumen. Figure courtesy of Dr Leszek Masłowski.

|

Degree of stenosis |

Treatment |

|

Patients with recent (<6 months) stroke or TIAa | |

|

<50% |

Pharmacotherapy |

|

50%-69% |

– Consider revascularizationa,b,d – Pharmacotherapy |

|

70%-99% |

– Revascularizationa,b,c – Pharmacotherapy |

|

Occluded or near-occluded |

Pharmacotherapy |

|

Patients without recent (<6 months) stroke or TIA | |

|

<60% |

Pharmacotherapy |

|

60%-99% |

– Pharmacotherapy – Consider revascularizationb,d in patients with life expectancy >5 years, favorable anatomy, and ≥1 feature suggesting higher risk of stroke with pharmacotherapye |

|

Occluded or near-occluded |

Pharmacotherapy |

|

a Revascularization should be performed as soon as possible (<14 days). b After a multidisciplinary discussion including neurologists. c CEA is preferred. Consider CAS in patients at high risk for CEA (age >80 years, clinically significant cardiac disease, severe pulmonary disease, contralateral internal carotid artery occlusion, contralateral recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, previous radical neck surgery or radiotherapy, recurrent stenosis after CEA). d Consider CEA. CAS may be considered as a second choice. e Contralateral TIA/stroke; ipsilateral silent infarction on cerebral imaging; ultrasonographic features: stenosis progression >20%, spontaneous embolization on transcranial Doppler, impaired cerebral vascular reserve, large (>40 mm2) or echolucent plaques, increased juxtaluminal hypoechogenic area; MRA features: intraplaque hemorrhage, lipid-rich necrotic core. | |

|

Adapted from Eur Heart J. 2018;39(9):763-816. | |

|

CAS, carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; CTA, computed tomography angiography; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; TIA, transient ischemic attack. | |