Pinto TCC, Machado L, Bulgacov TM, et al. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) screening superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's Disease (AD) in the elderly? Int Psychogeriatr. 2019 Apr;31(4):491-504. doi: 10.1017/S1041610218001370. Epub 2018 Nov 14. PMID: 30426911.

Breton A, Casey D, Arnaoutoglou NA. Cognitive tests for the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), the prodromal stage of dementia: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019 Feb;34(2):233-242. doi: 10.1002/gps.5016. Epub 2018 Nov 27. PMID: 30370616.

Tsoi KK, Chan JY, Hirai HW, Wong SY, Kwok TC. Cognitive Tests to Detect Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sep;175(9):1450-8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2152. PMID: 26052687.

Shi Q, Warren L, Saposnik G, Macdermid JC. Confusion assessment method: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1359-70. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S49520. Epub 2013 Sep 19. PMID: 24092976; PMCID: PMC3788697.

Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW. Neuropsychological Assessment. 4th ed. Oxford University Press; 2004.

IntroductionTop

The assessment of patients’ mental status at bedside has been a staple of medical inpatient units. Therefore, in this chapter we review a number of current bedside cognitive measures used most frequently in this context, which have been empirically validated in various settings, including inpatient medical settings. The selection of bedside cognitive measures is a matter of what symptoms are being evaluated, timely administration and scoring, and easily (and clearly) interpretable findings. However, not all bedside cognitive measures are created alike or have the ability to address global or specific cognitive losses.

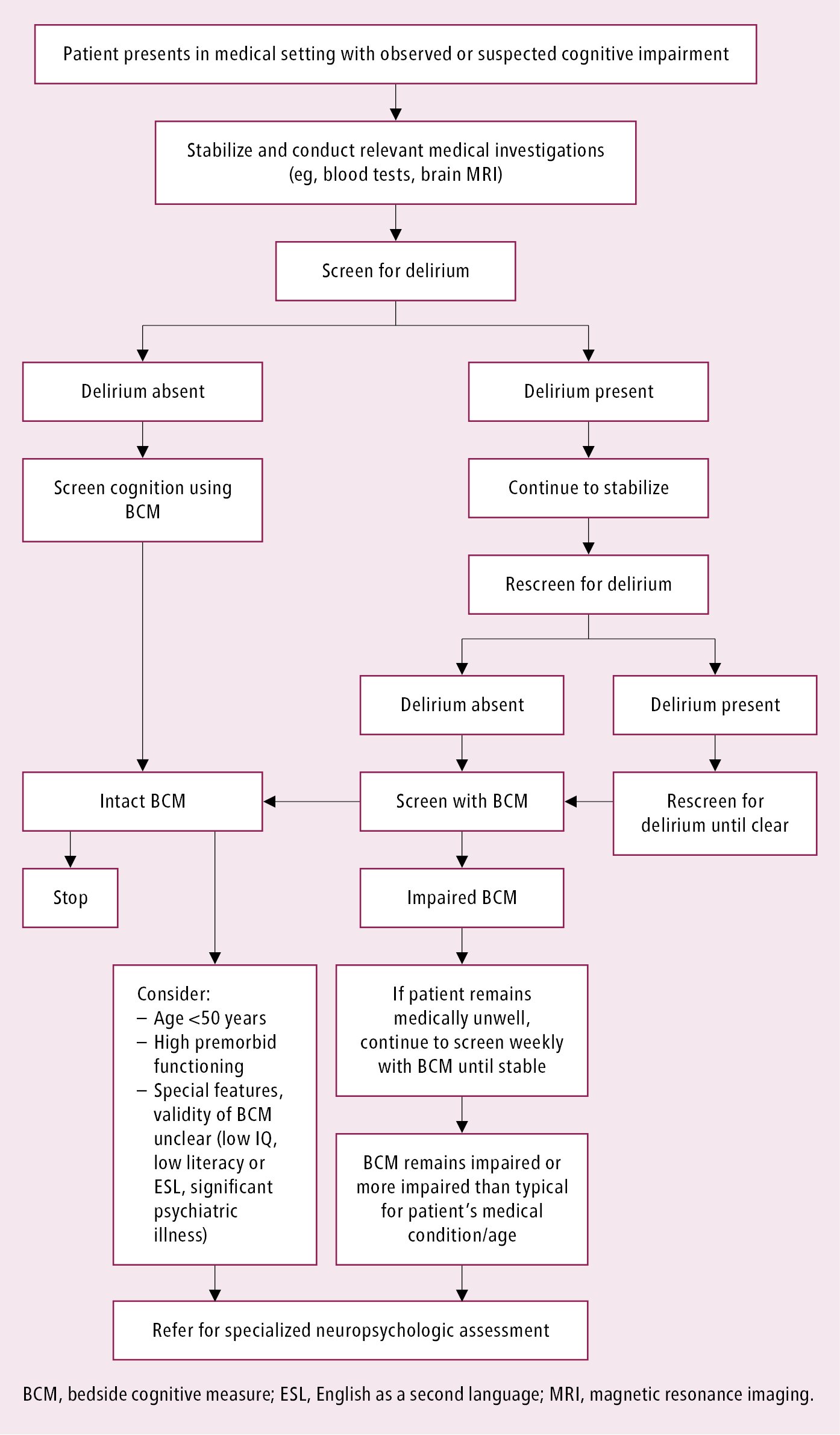

This chapter offers an evidence-based approach to the use of individual bedside cognitive measures, particularly in the context of specific medical syndromes (eg, delirium, dementia, disinhibited behavior). The goal is to anchor the clinician’s ability to choose, use, and make sense of the bedside cognitive measures. From the practical point of view, a good starting point may be to familiarize yourself with 1 or 2 of them, and then expand their range as the comfort of use and needs increase. An algorithm to guide clinicians in making the decision to refer for more specialized cognitive evaluations is also provided.

Typically Assessed Cognitive DomainsTop

Cognitive domains (or functions) represent various aspects of information processing. Typically, clinicians examine at least 7 areas, which are described below.

1. Orientation: Appraising the patient’s ability to be aware and integrate information from the environment, such as orientation to time, place, and person in the context of mental status examinations.

2. Attention: The ability to remain focused, selectively orient to specific targets in one’s environment, or tune out extraneous information in one’s environment.

3. Memory: The patient’s capacity to retain information for later adaptive use (eg, to remember a medical appointment or to pick up milk at the grocery store, or remember who the premier of the province is). Hence, in the context of assessing one’s memory, clinicians are looking at the individual’s ability to encode, store, and retrieve information.

4. Language: Defined as a system of symbols that enable individuals to communicate or interact in a meaningful manner. Clinicians often refer to language skills as the ability to listen, speak, name objects, follow commands, read, and write.

5. Perceptual and constructional domain: Distinguishing shapes, spatial relations (analysis) and dimensions; spatial integration (assembling, constructing).

6. Executive functions: An umbrella term that encompasses a variety of higher-order thinking skills and abilities. It is the ability to selectively deploy attention resources; organize, plan, and execute goal-directed behaviors; reason; form concepts; generate hypotheses; and self-monitor one’s behavior.

7. Behavior: Defined as the manner in which one acts or conducts oneself in relation to others. Characteristics may include being inattentive, confused, or aggressive.

Types of Cognitive Screening ToolsTop

Screening tests to investigate cognitive impairment in primary care settings that are short, simple, and easy to learn and perform, with high sensitivity and specificity, are also ideal in hospital medical settings. Some of the most commonly used general screening measures for bedside assessment are presented below (Table 16.7-1).

1. Mini-Cog: It is recommended as one of the best cognitive screening measures in general clinical practice. Consider using it when there are linguistic, cultural, and educational factors to contemplate. This test has lower false-positive rates compared with other screening measures and has been validated in older adults from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

The Mini-Cog is very brief and can be administered in <5 minutes, with no formal training required for administration. It can be used, reproduced, and distributed without permission in clinical settings. The test can be downloaded for free from www.mini-cog.com.

The Mini-Cog has 3 components: repetition of 3 unrelated words, a clock-drawing test, and delayed recall of the 3 words administered at the beginning of the test. One point is given for each word that the individual can recall after a delay, for a total of 3 points. The clock is scored either as normal (2 points) or abnormal (0 points). Scores of 0 to 2 are identified as “possible impairment,” while scores of 3 to 5 are indicative of “no impairment.”

2. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE): The MMSE is the most widely used cognitive screening test. It is available in many languages. This test is no longer available in the public domain, but it is commercially available for purchase from Psychological Assessment Resources (www.parinc.com). Its form and scoring can be reviewed at www.gov.bc.ca.

The MMSE consists of 11 questions that sample a range of domains: general orientation for time and place, encoding and delayed recall of 3 unrelated words, attention, 5 aspects of language, and construction. Each correct response is given 1 point, for a total score range of 0 to 30. Higher scores indicate better performance. Typically, a score of 23 or 24 points can be used as a cutoff to classify cognitive impairment. However, other different cutoff scores have been used to inform a more fine-grained classification of cognitive impairment: normal (27-30), moderate (11-20), and severe (0-10).

The MMSE is a good tool, recommended as a brief bedside assessment. It is also ideal for older adults who can only endure short periods of testing.

The MMSE is susceptible to age, literacy, education, and socioeconomic and cultural differences. It is generally insensitive with respect to identifying mild, severe, and focal impairments. Importantly, while it is suitable for older adults presenting with suspected delirium or dementia, clinicians are cautioned to use it as a diagnostic tool.

3. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): The MoCA is a widely used screening measure for the assessment of general cognitive function, specifically designed to identify mild cognitive impairment (MCI). It is suitable for individuals with memory difficulties whose MMSE score falls within the normal range.

The MoCA items measure 8 cognitive domains: orientation, attention/calculation, memory, visuospatial/visuoconstruction, 2 aspects of language, and 2 aspects of executive function. One point is awarded for each correct answer for a total score of 30, with higher scores representing better degrees of functioning. One point is added to the total score for those with ≤12 years of education who obtain scores <30. A score of 25 or 26 is used as a cutoff to classify MCI.

It is strongly recommended that any clinician choosing to administer, score, and interpret the MoCA is trained and certified in its standardized administration. Training and certification are now mandatory in order to access this publicly available instrument from the MoCA website (www.mocatest.org). As specified at this website, access to the test is no longer available after December 1, 2020, if training and certification have not been completed. The form and scoring of the test can be reviewed online at www.mdcalc.com.

4. Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-III (ACE-III): The ACE-III is the current modified and improved version of the previous Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACE-R). It has been used to distinguish early-onset dementia from healthy controls.

The ACE-III is comprised of 19 activities that measure 5 cognitive domains: attention, memory, fluency, language, and visuospatial processing. The results of each activity are scored to give a total score out of 100 (18 points for attention, 26 for memory, 14 for fluency, 26 for language, 16 for visuospatial processing). The score needs to be interpreted in the context of the patient’s overall history and examination. A score ≥88 is considered normal; <83 is abnormal; and between 83 and 87 is inconclusive. The ACE-III should not be used as a standalone screening tool to diagnose dementia or MCI in individuals presenting with or at risk for cognitive decline, but rather as an adjunct to a full clinical assessment. Its form and scoring can be reviewed in Psychiatry: Breaking the ICE: Introductions, Common Tasks and Emergencies for Trainees, Appendix D.2 (available online at www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com).

5. Cognitive Log (Cog-Log): The Cog-Log is a brief cognitive bedside assessment that can be used in rehabilitative settings for patients with severe cognitive and behavioral impairments after traumatic brain injury and for those who experienced hypoxia or stroke. It is a screening tool that can be administered at frequent intervals to monitor progress across different stages of rehabilitative treatment. The test can be administered in ≤10 minutes.

The Cog-Log is comprised of 10 items that capture 5 cognitive domains: orientation (3 items), anterograde memory (2 items), concentration (2 items), praxis (1 item), and executive ability (2 items). Each of these items is scored on a 4-point scale (0-3); 3 points are given for correct spontaneous answers and 2 points or 1 point for various degrees of accuracy that are defined for each item. The total score ranges from 0 to 30 (with higher scores indicating better cognitive functioning).

While some of the Cog-Log items can be given to nonverbal patients, several of the items require a verbal response. In cases of stroke and paralysis, the entire Cog-Log can be administered for patients with the use of at least one upper extremity. For those who are unable to use the upper extremities, 8 of the 10 items can be administered.

6. Additional bedside screening tests: Additional bedside screening tests that can be used to measure cognitive functions more extensively than with a general cognitive screening measure are summarized below (Table 16.7-2):

1) Confusion Assessment Method (CAM): It is a standardized evidenced-based method for diagnosing delirium in older adults. The test takes 5 to 10 minutes to administer and can be administered by clinicians in clinical or research settings. The CAM is suitable for administration to non-English speaking patients, as it has been translated into 10 languages. There is also a version that can be used in nonverbal mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU: the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU).

The CAM includes 4 features: acute onset and fluctuating course, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. The presence of delirium is indicated by a CAM algorithm of the features 1 and 2 plus either 3 or 4 (see Figure 16.8-3).

The form and scoring of the CAM can be reviewed at www.albertahealthservices.ca (CAM; under Educational Workshops, Supported Well, Living Well with Dementia) and www.mdcalc.com (CAM-ICU).

2) Memory Impairment Screen (MIS): The MIS is an objective clinician-administered test sensitive to the detection of early stages of dementia. It specifically assesses memory function (the earliest symptom of Alzheimer disease [AD]). Given its brief administration time (4 minutes) and ease of administration, it can easily be adapted for quick bedside assessment of memory function. No formal training is required to administer this test.

The MIS tests delayed free and cued recall of 4 words, each representing a different category. The 4 words are printed in 24-point uppercase letters on a piece of paper sized 21.5 × 28 cm. The patient is presented with the page and asked to read each word. The examiner points out that each of these words belongs to a different category and specifies which word belongs where. The patient is then provided with a category cue and asked to indicate which of the words belongs to the stated category. Up to 5 attempts are allowed and failure to complete this initial encoding task indicates possible cognitive impairment. After the patient has identified all 4 words correctly, the sheet of paper is removed. The patient is informed that they will be asked to remember the words after a few minutes and is then engaged in distractor activity for 2 to 3 minutes. In the delayed free recall that follows, patients are asked to recall as many of the 4 words as they can. Cued recall is provided for any words not recalling during the free recall.

Two points are given for each correct response to free recall and 1 point for the items retrieved following cued recall, for a total score range of 0 to 8, with higher scores indicating better performance. Scores of 5 to 8 are in a normal range, while scores ≤4 are suggestive of possible cognitive impairment. The MIS cannot be used with patients who are unable to read, whether due to a visual impairment or due to illiteracy. The form and scoring of the MIS can be reviewed at www.alz.org.

3) Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB): The FAB is a short bedside assessment of executive function that was designed for screening of frontotemporal dementia. It can also be used with other clinical populations with suspected executive functioning impairments. The FAB is subdivided into 6 subtests: conceptualization (3 items), mental flexibility (1 item), motor programming (6 trials), sensitivity to interference (3 trials), inhibitory control (3 items), and environmental autonomy (grasping behavior: 1 item).

Responses on these items are scored on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 to 3, with correct criteria (score of 3) individually operationalized for each item. The total score is from 0 to a maximum of 18, with higher scores indicating better performance. Different cutoff scores are used to distinguish different dementias. A cutoff score of 12 can be used to distinguish between frontotemporal dementia and AD. A higher cutoff score, of 14 or 15, distinguishes between progressive supranuclear palsy, multisystem atrophy, and Parkinson disease.

4) Clock-Drawing Test (CDT): The CDT is a free, short, and simple screening tool that can be used to quickly assess visuospatial and praxis abilities. It can also be helpful in identifying the presence of both attention and executive dysfunction. The test takes only a few minutes to administer. It can be used in inpatient settings, in situations where longer tests would be impossible or inconvenient to administer. The nonverbal nature of this test makes it suitable for patients with English as a second language. The CDT can be conducted in any language. No formal training is required to administer this test. A copy of the CDT can be downloaded from www.cgakit.com.

Choice of Appropriate ToolsTop

The selection of a bedside screening test (screener) is informed by its statistical parameters and the medical condition to examine. The selection of bedside cognitive measures in commonly observed conditions in medical settings is outlined below.

Patient characteristics with important implications on the selection of bedside cognitive measures and interpretation of results: Table 16.7-3.

1. Delirium: The CAM and CAM-ICU are commonly used evidence-based measures for identifying delirium. The CAM is designed to detect delirium in verbal patients, with a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 99%. The CAM-ICU assesses delirium in nonverbal patients, with a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 98%.Evidence 1Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias, heterogeneity, and imprecision. Shi Q, Warren L, Saposnik G, Macdermid JC. Confusion assessment method: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1359-70. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S49520. Epub 2013 Sep 19. PMID: 24092976; PMCID: PMC3788697. Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The Confusion Assessment Method: a systematic review of current usage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 May;56(5):823-30. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01674.x. Epub 2008 Apr 1. PMID: 18384586; PMCID: PMC2585541. Albeit the use of this tool is indicated, the possibility of false-negative findings is not trivial and therefore repeated measurements are recommended to improve diagnostic classification.

2. MCI: There is no consensus on the most accurate bedside cognitive measure for detecting MCI. The MoCA is recommended for assessing for MCI over the MMSE.Evidence 2Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias, small sample size for some cognitive screening tools, limited generalizability to hospital settings given community sampling, and imprecision (screening tests were not directly compared in the same populations). Breton A, Casey D, Arnaoutoglou NA. Cognitive tests for the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), the prodromal stage of dementia: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019 Feb;34(2):233-242. doi: 10.1002/gps.5016. Epub 2018 Nov 27. PMID: 30370616. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Apr;53(4):695-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. Erratum in: J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019 Sep;67(9):1991. PMID: 15817019. When considering MCI as a differential, it is important to use clinical judgment to interpret the results of cognitive screening in the context of the patient’s estimated premorbid cognitive functioning based on their history (eg, educational and vocational attainment).

3. Dementia: There are a number of bedside cognitive measures useful for identifying dementia. The Mini-Cog, ACE-III, and MoCA have demonstrated the highest sensitivities and specificities for the detection of dementia. In the absence of these measures the MMSE is an acceptable consideration, albeit it is less statistically robust than its counterparts above.Evidence 3Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias, small sample size for some cognitive screening tools, imprecision (screening tests were not directly compared in the same populations), and heterogeneity (screening tests were translated into various language). Tsoi KK, Chan JY, Hirai HW, Wong SY, Kwok TC. Cognitive Tests to Detect Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sep;175(9):1450-8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2152. PMID: 26052687. Pinto TCC, Machado L, Bulgacov TM, et al. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) screening superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's Disease (AD) in the elderly? Int Psychogeriatr. 2019 Apr;31(4):491-504. doi: 10.1017/S1041610218001370. Epub 2018 Nov 14. PMID: 30426911. Beishon LC, Batterham AP, Quinn TJ, Nelson CP, Panerai RB, Robinson T, Haunton VJ. Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination III (ACE-III) and mini-ACE for the detection of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Dec 17;12(12):CD013282. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013282.pub2. PMID: 31846066; PMCID: PMC6916534. Brodaty H, Low LF, Gibson L, Burns K. What is the best dementia screening instrument for general practitioners to use? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006 May;14(5):391-400. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000216181.20416.b2. PMID: 16670243.

While bedside cognitive measures are useful for differentiating healthy controls or MCI from dementia, their utilities in identifying underlying etiology are limited. Considerations for several specific types of dementia are provided below.

1) AD: The cognitive profile of AD typically involves predominant memory impairment with poor learning and retention. There can also be deficits in attention, executive functioning, confrontation naming, and visuospatial abilities. Both bedside cognitive screening tools and informant-based measures are useful in identifying AD. The Alzheimer’s Questionnaire is a brief (taking 3 minutes to complete), validated, informant-based measure sampling orientation, functional abilities, and cognition, with high diagnostic accuracy for detecting AD. The form and scoring of the test can be reviewed at www.gov.bc.ca (under Diagnosis).

2) Frontotemporal dementia (FTD): While bedside cognitive screeners can be useful for detecting cognitive impairments in FTD, it can be challenging to differentiate between the FTD phenotypes and other types of dementia. The FAB is an executive functioning screening measure useful in differentiating FTD and AD. Behavioral measures such as the Frontal Behavioral Inventory (FBI), a 24-item inventory sampling behavior, cognition, communication, and language amongst other domains, can also be helpful in identifying FTD versus other dementias. The timeline of symptom onset should also inform the differential diagnosis. The form and scoring of FTD can be reviewed at www.psychscenehub.com.

Additional neurologic or cognitive testing may be required for diagnostic clarification. Specific considerations for FTD phenotypes that have been identified include:

a) Behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD): Characterized by a prominent behavioral change involving apathy, disinhibition, executive dysfunction, or all of these. In this context our preferred instrument would be the MoCA.

b) Semantic dementia (ie, semantic variant primary progressive aphasia [svPPA]): Involves fluent speech with deficits in confrontation naming, word comprehension, and object knowledge. Word substitution (eg, toaster instead of oven) or difficulties reading irregular words (ones that do not sound the way they are spelt, eg, debt) may also be present. Language-based screeners that include object naming, auditory comprehension, and fluency are the most useful measures (eg, MoCA, MMSE).

c) Progressive nonfluent aphasia (ie, nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA): Nonfluent, effortful, and agrammatic speech with spared word comprehension and object knowledge. We offer the same approach as above, using either the MoCA or MMSE.

d) Corticobasal degeneration: Cognitive profile characterized by prominent executive dysfunction and poor learning and motor coordination. We offer the same approach as the one noted above (MoCA or MMSE).

e) Progressive supranuclear palsy: The typical cognitive deficits include slow processing speed, inattention, poor verbal fluency, and memory impairment in recall. We offer the same approach as above, to use either the MoCA or MMSE.

3) Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): DLB involves deficits in attention, executive functioning, and visuospatial impairment. One of the key clinical features of DLB is fluctuations in cognition over time (minutes to hours), including observational data pertaining to slowed movements, stiffness, uncontrolled shaking (tremors), sleep disturbances, fainting spells, and falls.

4. Cerebrovascular disease (CVD): Vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) is an umbrella term that encompasses the range of cognitive impairments due to CVD, ranging from vascular MCI to vascular dementia. The MoCA is more sensitive to VCI than the MMSE, but it lacks the same degree of specificity. The typical cognitive profile involves impairments in complex attention, processing speed, executive functioning, and memory (ie, poor encoding and retrieval). More isolated cognitive deficits can be seen in the case of cerebrovascular accident, depending on the location of the stroke. Language deficits, motor deficits, or both can make the administration of bedside cognitive screener difficult.

5. Traumatic brain injury (TBI): The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (see Table 1.5-2) is a measure of consciousness in patients with acute brain injury, with widespread use in the initial evaluation of TBI. Lower GCS scores are associated with an increased risk of severity in TBI, in-hospital mortality, and functional dependence post injury. The validity of the GCS is compromised when patients have been sedated or intubated. Bedside cognitive measures such as the MoCA and MMSE can be used to screen for cognitive impairment in patients with TBI during acute-care hospitalization and are predictive of the level of disability at discharge. Another useful screening tool is the Galveston Orientation and Amnesia Test (GOAT), which measures orientation and memory for events preceding and following the injury. GOAT scores are correlated with functional ability at discharge and employment status 1 year post injury. The form and scoring of the test can be reviewed at www.scale-library.com.

Referral for Specialized Neuropsychological assessmentTop

Algorithm for referral for specialized neuropsychological assessment: Figure 16.7-1.

A number of factors can contribute to a decision to refer for specialized neuropsychological assessment, as outlined below.

1. Busy inpatient medical environment: It can be challenging to determine if the current change in cognitive status is situational and likely to resolve with minimal intervention, such as an acute alteration secondary to the medical condition itself or to the psychological distress associated with an acute exacerbation of a preexisting chronic medical condition, or acute onset of an illness or injury.

2. Insufficiency of bedside cognitive measures: The bedside cognitive measure may not be sensitive enough to ascertain if the observed or suspected cognitive impairment is in keeping with what would be expected. For example, a patient with premorbid intellectual disability or borderline IQ may fail standard cognitive screening such as the MoCA, but this impairment may be longstanding. Alternatively, an individual with above-average premorbid IQ may appear intact on cognitive screening but may have experienced a decline in cognition that is too subtle—compared with prior level of ability—to be detected by screening yet may have important implications for the patient’s recovery, rehabilitation, return to premorbid level of social and occupational functioning, or all of these.

3. Doubts concerning the patient’s cognitive functioning: In more complex cases, when the etiology or characteristics of the cognitive status remain unclear after using bedside cognitive measures, consultation with specialized neuropsychology services would be recommended. The most common clinical situations when a neuropsychologic assessment can be helpful in addressing clinical questions: Table 16.7-4.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Test |

Public domain |

Administration time |

Languages |

Source |

|

Mini-Cog |

Yes |

≤5 min |

16 |

Can be downloaded for free in English or other languages from www.mini-cog.com |

|

MMSE |

No |

5-10 min |

>50 |

Commercially available for purchase at www.parinc.com A list of authorized foreign language translations of the MMSE can also be found on this website |

|

MoCA |

Yes |

10-15 min |

~100 |

Available to trained and certified healthcare clinicians (training and certification is mandatory since September 1, 2019). Can be downloaded from www.mocatest.orga |

|

ACE-IIIb |

Yes |

15 min |

30 |

Can be downloaded from www.sydney.edu.au All 30 translated versions also available for download |

|

Cog-Log |

Yes |

≤10 min |

Not specified |

Can be downloaded from www.tbims.org |

|

a From December 1, 2020, access to the test from this website is not possible if training and certification are not completed. b Current version that replaces former ACE-R. | ||||

|

ACE-III, Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-III; ACE-R, Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised; Cog-Log, Cognitive Log; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment. | ||||

|

Test |

Cognitive domain |

Administration time |

Languages |

Public domain/source |

|

CAM |

Delirium |

5-10 min |

10 |

Yes. CAM-ICU: www.mdcalc.com |

|

FAB |

Executive functioning |

10 min |

5 (Portuguese, German, Spanish, Chinese, Japanese) |

Yes. Can be downloaded from www.psychdb.com, a free psychiatry reference website |

|

MIS |

Memory |

4 min |

Not specified |

No, but items and scales are available from the authors |

|

CDT |

Spatial/praxis |

1-2 min |

Can be conducted in any language |

Yes. Can be downloaded for free from www.cgakit.com |

|

CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; CDT, Clock-Drawing Test; FAB, Frontal Assessment Battery; MIS, Memory Impairment Screen. | ||||

|

Age |

Attention, processing speed, memory, and conceptual reasoning gradually decline with normal aging. Semantic knowledge can improve with age. It is preferable to ensure that the measure has been validated in the patient’s age group (eg, MoCA has been validated for ages 55-85, but there are age-adjusted norms across ages 18-99). |

|

Level of education and literacy |

Cognitive screening tools can underestimate the abilities of a patient with limited education or miss subtle cognitive impairment in those with a high level of education. Level of education is often seen as a simple proxy for premorbid cognitive ability. However, many people do not have the opportunity to access education regardless of their aptitude and education benefits cognitive performance over and above baseline ability. |

|

Language |

Testing in a nondominant language can underestimate cognitive performance even if the person appears to be relatively fluent. Commonly used screening measures are usually available in a number of different languages (eg, MoCA is available in nearly 100 languages). |

|

Culture |

Clinicians are encouraged to consider relevant cultural factors when selecting bedside cognitive screeners. Certain items and constructs can vary in validity across cultures. Studies across cultures yield variable levels of validity, sensitivity, and specificity for both the MMSE and MoCA. |

|

Comorbid conditions |

Visual impairment: A viable measure is the MoCA Blind, which has good sensitivity and specificity for detecting dementia. The Telephone MMSE lacks sensitivity. Hearing impairment: There is a version of the MoCA available for patients with severe hearing impairment (HI-MoCA). Intellectual disability: A patient with an intellectual disability or developmental disorder could score in the impaired range on a cognitive screening tool at baseline, so a careful history should be taken to clarify whether there has been a cognitive or functional decline. Psychiatric disorders: Patients with psychiatric disorders score lower than healthy controls on cognitive screening measures. Failure to consider the impact of psychiatric conditions on cognitive screening scores could result in misdiagnosis of MCI or dementia and delay patient access to appropriate mental health treatment. |

|

MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment. | |

|

Medical conditions |

– Cerebrovascular disorders (stroke) and risk factors – Seizure disorders – Traumatic brain injury – Neurodegenerative disorders (Parkinsonian syndromes) – Brain tumors (post surgery/radiation/chemotherapy) – Central nervous system infections – Multiple sclerosis – Complex multiple systemic medical conditions |

| Clinical questions to address |

– Differential diagnosis – Identifying cognitive strengths and weaknesses – Determining changes/dysfunction in cognition in terms of presence and severity of impairment – Determining whether changes/dysfunction in cognition are associated with neurologic disease, neuropsychiatric disorders, systemic medical conditions, or are multifactorial – Monitoring cognition over time to assist with determining a prognosis – Providing treatment guidelines, expectations, and education for treatment teams, caregivers, and family |

Figure 16.7-1. Algorithm for referral for specialized neuropsychological assessment.