Gudzune KA, Kushner RF. Medications for Obesity: A Review. JAMA. 2024 Aug 20;332(7):571-584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.10816. PMID: 39037780.

Canadian Adult Clinical Practice Guidelines. Obesity Canada. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://obesitycanada.ca/guidelines/chapters

Canada’s Dietary Guidelines. Government of Canada. Accessed December 4, 2020. https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/guidelines/what-are-canadas-dietary-guidelines

Pilitsi E, Farr OM, Polyzos SA, et al. Pharmacotherapy of obesity: Available medications and drugs under investigation. Metabolism. 2019 Mar;92:170-192. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.10.010. Epub 2018 Nov 1. PMID: 30391259

Brauer P, Gorber SC, Shaw E, et al; Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations for prevention of weight gain and use of behavioural and pharmacologic interventions to manage overweight and obesity in adults in primary care. CMAJ. 2015 Feb 17;187(3):184-195. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140887. Epub 2015 Jan 26. PMID: 25623643; PMCID: PMC4330141.

Gonzalez-Campoy JM, St Jeor ST, Castorino K, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; American College of Endocrinology and the Obesity Society. Clinical practice guidelines for healthy eating for the prevention and treatment of metabolic and endocrine diseases in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/the American College of Endocrinology and the Obesity Society. Endocr Pract. 2013 Sep-Oct;19 Suppl 3:1-82. doi: 10.4158/EP13155.GL. PMID: 24129260.

Lau DC, Douketis JD, Morrison KM, Hramiak IM, Sharma AM, Ur E; Obesity Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Panel. 2006 Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children [summary]. CMAJ. 2007 Apr 10;176(8):S1-13. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061409. PMID: 17420481; PMCID: PMC1839777.

Lifestyle TreatmentTop

Obesity is a chronic progressive medical condition that requires lifelong lifestyle changes, including nutrition, physical activity, and behavioral modification.

Nutritional modification can result in modest weight reduction and a decrease in waist circumference (WC) as well as in an improvement in health and quality of life. The main goal of modifying nutrition plans is to provide safe, nutritionally adequate, and sustainable dietary guidance targeting an adequate intake of essential micronutrients and macronutrients, individualized to each patient. Short-term or very restrictive dietary changes are often not sustainable and have a high risk of weight regain.

In general, a caloric deficit of 500 to 750 kcal of the daily current intake can produce an average weight loss of 0.5 to 1 kg per week; however, meal plans should be tailored to an individual’s total energy requirements. Rapid weight loss is not recommended and can cause a more significant decrease in lean muscle mass and reduction in energy expenditure. Eating <1200 kcal daily is generally not recommended due to an increased risk of nutritional deficiencies and should be medically supervised if undertaken.

Nutrition plans should be focused on achieving long-term, sustainable changes to help improve comorbidities and quality of life and reduce adiposity. Weight loss should not be the primary focus. All nutrition plans should consider the patients’ cultural, socioeconomic, and physiologic needs. Patients should receive general recommendations to guide their food choices and eating behavior (see Table 6.5-1). Dietitians can provide helpful support in curating individual treatment plans for patients. Specialized nutrition plans should be considered for patients post bariatric surgery; those with nutritional deficiencies, eating disorders, or renal or hepatic impairment; and the elderly. Key aspects of different nutrition plans: see Table 6.5-2.

Nutritional studies are generally of poor quality and mainly observational. Improved outcomes in body weight, body mass index (BMI), WC, glycemic control, lipid profiles, and blood pressure (BP) can be seen with appropriate nutrition plans; however, long-term weight maintenance is often challenging due to counterregulatory responses of decreased energy expenditure and increased hunger hormones seen with weight loss. Most calorie-restricted dietary plans with variable macronutrient goals (carbohydrate, protein, and fat percentages of total calories) help achieve a similar weight reduction over 6 to 12 months, which is ~3% to 5% of total body weight.

As no single nutrition plan has shown consistent success with long-term weight maintenance, choosing a plan that best suits the patient and can be adhered to in the long term should be prioritized.

Physical activity is an important component of lifestyle modification and can help promote weight maintenance and weight loss and prevent weight regain. Physical activity goals should aim to be sustainable and enjoyable and should reduce sedentary time. These goals should be tailored to each patient and can include a variety of forms, such as sports, formal exercise training, walking the dog, or playing with children. Benefits that are independent of weight loss can be seen with increased activity, including improved cardiovascular fitness, sleep, stress, mobility, body composition, and body image. Although weight loss may not be seen with increased physical activity, clinically important improvements in blood glucose, lipid levels, and BP can be observed, along with improvements in fat mass, lean muscle mass, strength, and body composition.

The American Heart Association, Diabetes Canada, and many other authorities in chronic diseases generally recommend ≥150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity per week. Physical activity should be distributed over ≥3 days per week, with ≤2 consecutive days without activity, and should be supplemented by increase in daily lifestyle activities and include resistance training. Targets for activity should be individualized for each patient to be achievable and sustainable.

Exercise prescriptions outlining the type, duration, intensity, and frequency are recommended in order to help individualize physical activity goals and encourage self-directed goals. Examples of patient-centered goals include walking the dog at a moderate pace for 30 minutes 3 times per week. The overall goal is to reduce sedentary time gradually and avoid the risk of injury with increased physical activity.

Increased amounts of physical exercise are needed for long-term weight maintenance due to compensatory changes in hormones and decreased energy expenditure seen with weight loss. Often 250 to 300 minutes of moderate or vigorous aerobic physical activity per week is required for weight maintenance and to prevent weight regain after weight loss.

Behavioral modification refers to techniques that help increase or decrease a particular behavior and relies on concepts of classical and operant conditioning. It is required in all aspects of obesity management in order to be successful with treatment and is often overlooked or defined as “lifestyle changes” with a sole focus on nutrition and activity-based goals. The most effective lifestyle treatment programs offer interventions with calorie-reduced nutrition plans and with physical activity goals delivered with behavioral therapy support.

Understanding the patient’s underlying stimulus to eat, including the potentially imbalanced homeostatic system that regulates satiety and hunger, cravings from the hedonic pathway, and the relationship with food through associative learning, are important steps in changing behavior. In addition, identifying internalized biases (eg, negative self-image) and strengthening coping skills can lead to improved outcomes.

Selected skills and techniques in behavioral modification include:

1) Self-monitoring (eg, food diaries).

2) Goal setting (using SMART [specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-based] goals).

3) Stimulus control.

4) Identifying triggers (eg, holidays, boredom, stress).

5) Problem solving (identifying the problem, understanding the cause, generating solutions, and using coping skills).

6) Action planning.

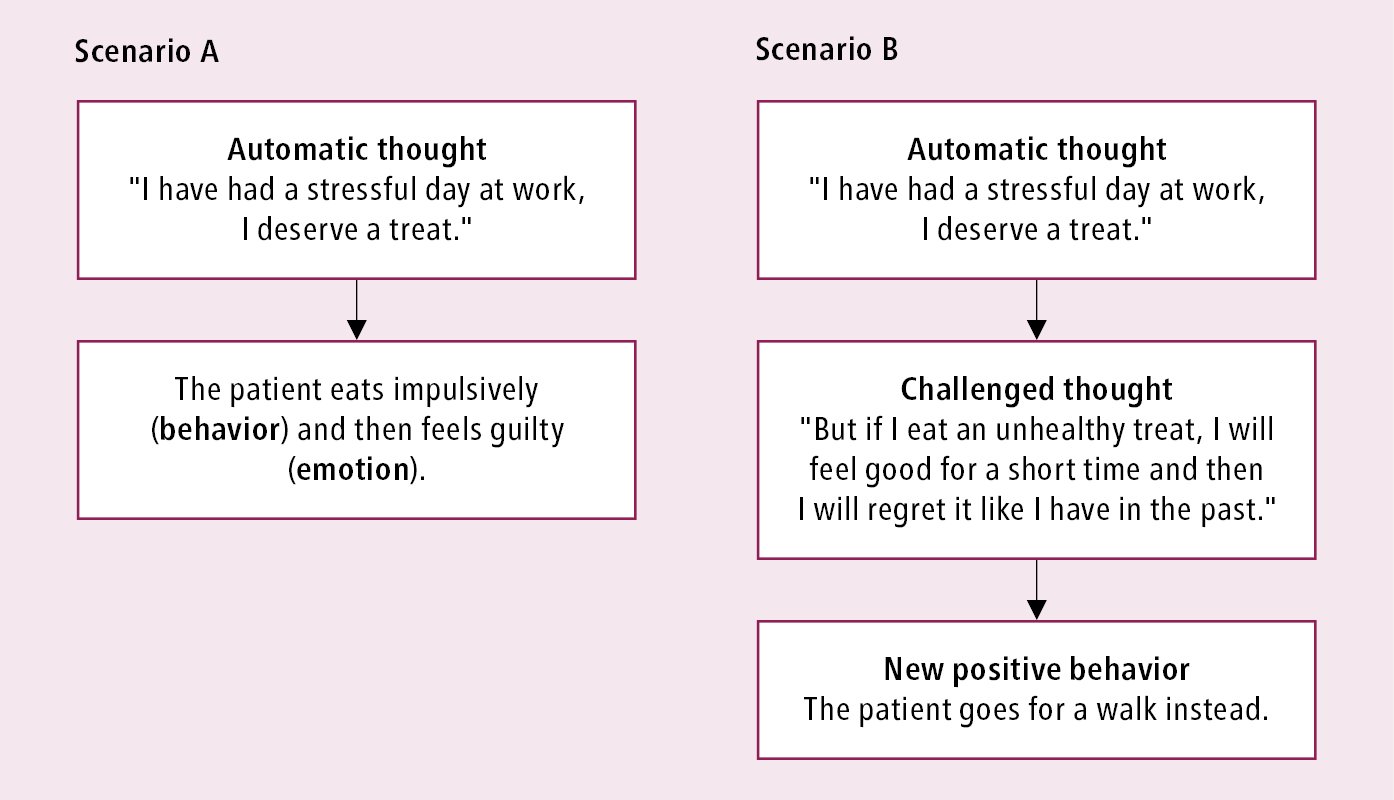

7) Cognitive restructuring (Figure 6.5-1): The 3 steps to cognitive restructuring are to identify an automatic thought, challenge the thought, and create a new positive thought and behavior.

8) Motivational interviewing.

9) Stress management.

10) Resiliency and reward management.

Resources and tools to master these skills are needed as an important part of behavioral management in obesity treatment and should be reviewed with each patient. There are often mental health and psychologic barriers to successful treatment. Psychologic treatment is often required as part of behavioral counseling and can be delivered through cognitive or acceptance-based treatment models. Depression, attention deficit, hyperactivity disorder, and anxiety occur at a higher rate in people living with obesity. Patients should be offered mental health support and counseling if needed.

Pharmacologic TreatmentTop

Pharmacotherapy is an important adjunct to lifestyle modification in the treatment of obesity for patients with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 or BMI ≥27 kg/m2 with adiposity-related complications (see Obesity: General Considerations). Approved medications have been shown to be beneficial for long-term weight reduction and prevention of weight regain and comorbidities related to weight in comparison with lifestyle changes alone.

Variable responses to pharmacotherapy are often seen due to the multifactorial etiology of obesity including biologic, genetic, and physiologic changes that are unique to each patient.

If patients do not achieve ≥5% weight reduction after 12 weeks on a full dose or maximally tolerated dose of medication for weight management (and no other etiology for the lack of success is identified), the medication should be reassessed and alternative options should be considered. Effective medications should be continued in the long term in order to avoid weight regain.

Medications should be tailored to each patient based on their mechanism of action, adverse effects, safety, and tolerability of each agent. The cost of medications as well as the mode (oral versus subcutaneous) and frequency of administration can be a barrier to the patient’s adherence and should be discussed. It is important to assess concomitant medications that the patient is taking as possible contributors to weight gain and to consider alternatives where appropriate.

Summary of common pharmacologic agents for obesity: Table 6.5-3.

Lorcaserin (a selective serotonin 2C receptor agonist) has been recalled by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2020 due to an increased risk of certain cancers (including pancreatic, colorectal, and lung cancers) and is therefore no longer recommended and should be discontinued in those who are taking it. All pharmacologic agents for weight management are contraindicated in pregnant and breastfeeding women. Women of childbearing age should be counseled about potential pregnancy-related risks.

With the availability of newer, more effective medications, it is crucial to make sure that patients maintain their healthy eating habits and participate in resistance exercises to preserve their lean muscle mass and avoid complications such as sarcopenic obesity (high body fat percentage with loss of muscle mass and function). Some of the latest anti-obesity drugs can lead to weight loss comparable with that achieved through bariatric surgery, which is a positive outcome for improving comorbidities associated with obesity. However, it is also important to avoid excessive weight loss, which can lead to negative physical and mental outcomes, and patients should be counseled accordingly. While it may seem that the newer anti-obesity medications are more effective and make other options less desirable, like in all chronic diseases, having more options is generally better because they differ in the mode of administration, cost, and adverse-effect profiles.

Tables AND FIGURESTop

|

Make patients aware of the nutritional value of their meals. Advice can include the following recommendations: – Eat plenty of vegetables and fruits, wholegrain foods (eg, wholegrain oats, brown rice), and protein foods (eg, lean meats, legumes, nuts, seeds) and choose protein foods that come from plants more often. – Choose foods with healthy fats (eg, nuts, seeds, avocado) and reduce saturated fats (processed meats, high-fat dairy, cream). – Limit highly processed foods (eg, packaged snacks like chips, cookies, sugary drinks, fast foods) or eat them less often and in small amounts. – Prepare meals and snacks using ingredients that have little to no added sodium, sugars, or saturated fat. – Choose healthier menu options when eating out. – Make water your drink of choice, replace sugary drinks with water. – Read food labels (eg, information on serving size, calories, certain nutrients, and percent daily value [%DV]) as well as lists of ingredients.a – Remember that food marketing can influence your choices. |

|

Healthy eating is more than the foods we eat. It is also about where, when, why, and how we eat. Advice can include the following recommendations: – Be mindful of your eating habits. – Take time to eat. – Notice when you are hungry and when you are full. – Cook more often. – Plan what you eat. – Involve others in planning and preparing meals. – Enjoy your food. – Remember that culture and food traditions can be a part of healthy eating. – Eat meals with others. |

|

a Consult Canada’s Dietary Guidelines at food-guide.canada.ca for details. |

|

Dietary plan |

Description |

Benefits |

Limitations |

|

Mediterranean diet |

Rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, beans, nuts and seeds, olive oil |

Improved metabolic parameters (blood glucose, TG, HDL-C, BP), reduced number of cardiovascular events |

Small effect on body weight |

|

Low-GI diet |

Focus on carbohydrate-containing foods that are less likely to cause large increases in blood glucose, foods ranked 1-100 (low GI, 1-55). Examples of low-GI foods: green vegetables, most fruits, raw carrots, kidney beans, chickpeas, lentils, bran breakfast cereals |

Improved glycemic control, lower BP, lower risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease |

No guidance on portion sizes, does not take nutrition into account |

|

Vegetarian diet |

Abstaining from meat or meat byproducts |

Improved glycemic and lipid control (including LDL-C), reduced body weight, reduced coronary heart disease incidence and mortality |

Risk of micronutrient deficiency (eg, vitamin B12) |

|

DASH dietary pattern |

4-5 servings of vegetables/d; 4-5 servings of fruits/d; 7-8 servings of grains (mainly whole grains)/d; 2-3 servings of low-fat or no-fat dairy foods/d; ≤2 servings of lean meats, poultry, and fish/d; 2-3 servings of fats and oils/d; 4-5 servings of nuts, seeds, and dry beans/wk |

Reduced body weight and waist circumference, lower blood pressure, lower lipid (including LDL-C) and CRP levels; lower risk of cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke |

|

|

Partial meal replacement (replacing 1-2 meals/d as part of a calorie-restricted intervention) |

Usually provides 200-250 calories/serving; fortified with vitamins and minerals |

Rapid weight loss, reduced waist circumference, lower blood pressure, improved glycemic control |

Inconsistent data on long-term weight loss and weight maintenance |

|

Reduced-carbohydrate diet |

– Low-carbohydrate diet: <45% of calories from carbohydrates – Very low–carbohydrate diet: ≤20-50 g of carbohydrates/d – Ketogenic diet: very low carbohydrate content with most calories coming from high-fat foods |

Greater fat and weight loss at 6 months vs low-fat diet, no difference at 12 months; improved TG and HDL-C values |

No effect on BP, higher LDL vs low-fat diet at 6 months |

|

Intermittent fasting |

– Fasting for varying periods during the day (typically ≥12 h) – Alternate day fasting (no calorie intake on fasting day, unrestrictive food intake on feasting days) |

Increased insulin sensitivity, possible reduced desire to eat and increased satiety, improved BP |

No differences in HbA1c, weight, fat mass, fat free mass, and BMI between IF and continuous calorie restriction |

|

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CRP, C-reactive protein; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stopping Hypertension; GI, glycemic index; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglyceride. | |||

|

Availability |

Mechanism of action |

Dose |

Common adverse events and contraindications |

Efficacy in kg/% of body weight loss (1 year, placebo subtracted, ITT population) |

|

Orlistat |

||||

|

US (FDA has approved orlistat for children aged ≥12 years), Canada, Europe |

GI lipase inhibitor (decreases fat absorption) |

120 mg PO tid with meals |

GI: oily spotting, gas with discharge, fecal urgency, fatty or oily stools, increased defecation, fecal incontinence |

~3% |

|

Phentermine/topiramate |

||||

|

US |

Amphetamine analogue/anticonvulsant |

3.75/23 mg to 15/92 mg PO daily |

Xerostomia, paresthesia, insomnia, constipation, dysgeusia, and dizziness; contraindicated in patients with glaucoma, hyperthyroidism, concomitant use of MAOIs; known hypersensitivity or idiosyncrasy to the sympathomimetic amines |

6.7 kg/6.6% (dose, 7.5/46 mg) 8.8 kg/8.6% (dose, 15/92 mg) |

|

Liraglutide (3.0 mg/d) |

||||

|

US, Canada, Europe |

GLP-1 receptor agonist (increases satiety, delays gastric emptying, decreases food reward) |

0.6 mg/d SC, increase by 0.6 mg/wk until target dose of 3.0 mg/d SC is reached |

Nausea, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting and headache; contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of MTC or in patients with MEN 2, MEN 3, or pancreatitis |

4%-5.4% |

|

Semaglutide (2.4 mg/wk) SC |

||||

|

US, Canada/Europe |

GLP-1 receptor agonist (increases satiety, delays gastric emptying, decreases food reward) |

Weekly SC injections: 0.25 mg for 4 weeks, 0.5 mg for 4 weeks, 1.0 mg for 4 weeks, 1.7 mg for 4 weeks; target dose: 2.4 mg SC/wk |

Nausea, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting and headache; contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of MTC or in patients with MEN 2, MEN 3, or pancreatitis |

12.5% |

|

Tirzepatide |

||||

|

US, approved only for type 2 diabetes in Canada and Europe |

Dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist (increases satiety, delays gastric emptying, decreases food reward) |

Weekly SC injection, 3 therapeutic doses: 5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg Start at 2.5 mg/wk and increase by 2.5 mg every 4 weeks until therapeutic dose is reached |

Nausea, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting and headache; contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of MTC or in patients with MEN 2, MEN 3, or pancreatitis |

11.9% (5 mg dose), 16.4% (10 mg dose), 17.8% (15 mg dose) |

|

Naltrexone HCl/bupropion HCl |

||||

|

US, Canada, Europe |

Opioid receptor antagonist/dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (decreases cravings from the mesolimbic reward system and hunger) |

8/90 mg/d (1 tablet) PO, increase by 1 tablet/wk until target dose of 2 tablets PO bid is reached |

Nausea, constipation, headache, vomiting, dizziness, insomnia, dry mouth, and diarrhea; contraindicated in uncontrolled hypertension, seizure disorders, patients using other bupropion-containing products, in bulimia or anorexia nervosa (increases the risk of seizures), chronic opioid use, abrupt discontinuation of alcohol intake, with benzodiazepines, barbiturates, antiepileptic drugs, and MAOIs |

3.3%-4.8% |

|

bid, 2 times a day; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; GI, gastrointestinal; GIP, glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; ITT, intention to treat; MAOIs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors; MEN 2, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2; MEN 3, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 3; MTC, medullary thyroid cancer; PO, oral; SC, subcutaneous; tid, 3 times a day. |

||||

Figure 6.5-1. Example of automatic thinking (scenario A) and cognitive restructuring for behavioral modification (scenario B).