Dr Zain Chagla, associate professor at the Faculty of Health Sciences at McMaster University, and Dr Roman Jaeschke talk about the recently reported cases of monkeypox and summarize the most important facts about etiology, presentation, and treatment.

Roman Jaeschke, MD, MSc: Good morning. Please welcome our infectious diseases star consultant, Professor Zain Chagla. The topic of today would be monkeypox, a somehow confusing topic to probably a lot of us. In preparation here I was trying to read about smallpox, chickenpox, cowpox, monkeypox… and it all blurred. Maybe we could start, Zain, by putting it somehow into a historical perspective.

Zain Chagla, MD, MSc: Yeah, absolutely. There really are these 3 viruses you have just talked about: smallpox, monkeypox, cowpox, and, I guess, chickenpox. So, just to [put a] delineating line, chickenpox is the odd one out of those 3 in the sense that it is a herpes virus, a varicella zoster virus, which is a completely separate family, separate genome, etc. Then you have this family of orthopoxviruses, which are large DNA viruses, which include smallpox, [monkeypox], and cowpox.

Smallpox, we all know, is the historic cause of pox-like lesions, high mortality, a disease that ravaged Europe and the rest of the world through the 1500s, 1600s, and 1700s. Eventually Jenner developed a vaccine from another related virus—cowpox virus, the Vaccinia virus—which is our derivative of vaccine, which was used to create immunity to smallpox and, in fact, to create vaccines in general.

And then monkeypox, which was discovered in the 1970s in monkeys and then subsequently has been seen in other animal and rodent vectors in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Central and West Africa, was described [and] had multiple outbreaks within Central and West Africa. And then, now, in the last 2 decades, it has had some outbreaks that have also reached outside of sub-Saharan Africa: in 2003 in the United States, associated with rodents that were imported from West Africa; in 2017, 2018, and 2019, from travelers, particularly from Nigeria; and then, most recently [there has been] a large outbreak that really is not associated with travel and is not associated with animal exposures.

Roman Jaeschke: What happened? That is one way of putting it. And the other one is, why the sudden interest? I mean, you mentioned there is an outbreak. What is going on?

Zain Chagla: It is a good question. Again, most of the events that have happened to date have been spillover events [linked] to travel from people who were in Nigeria or the Democratic Republic of Congo. This is different in the sense that they were individuals who had no travel history, no animal exposure history, and predominantly were gay or men who have sex with men (MSM). And [there is] some question of whether or not this was sexually acquired or contact-acquired during sexual activity, presenting more [often] with genital lesions, but leading to a significant number of cases. In fact, [this is] the largest number of cases that have been reported outside of western and Central Africa in the history of the monkeypox era and since 1970. This has been now noted in multiple continents, multiple countries, and, again, predominantly in the gay/MSM category, although there are some cases that have been noted outside of that. Again, genital lesions, oral lesions, a little bit clinically different [course] from the classic pox-like presentation, generally not very unwell individuals. Many have remained out of hospital, but the numbers that are increasing by the day and as prospective surveillance is now turning into more opportunities to diagnose and identify patients, [we have] more cases that are adding up consequentially.

Roman Jaeschke: So, would you say it is growing rapidly or slowly? Or plateaued?

Zain Chagla: You know, as we compare [it] with things like coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the growth is much slower. The reproductive rate is estimated to be ~1.2 to 1.3, so not as many people [get] infected with a single case. I think there are other features here that... You know, we are seeing much more growth now, but, again, that may be due to the fact that people are identifying this more easily, they are looking for it more easily. Especially looking at some of the clinical pictures of people who have presented early in England and in Canada, it could very well be mistaken for some other genital ulcer disease like herpes simplex, syphilis, chancroid, and other infections, [and] often could be treated syndromically and not necessarily with a clinical or microbiologic diagnosis. Now that it has been identified as a potential issue in this population, more people are getting testing and more people are being diagnosed properly. [There is also] contact tracing, which is identifying more cases appropriately.

Roman Jaeschke: So, how does this disease usually present itself? What should we be alerted to?

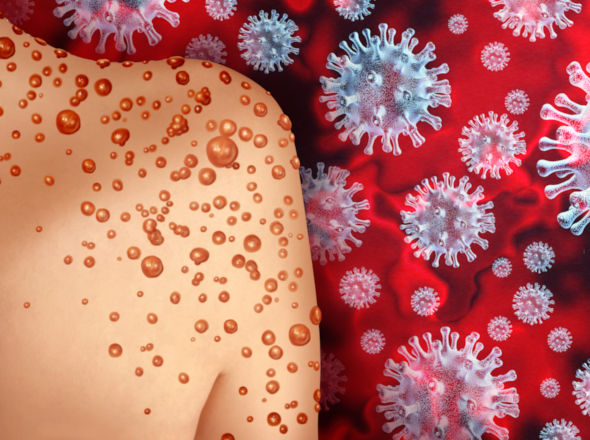

Zain Chagla: The typical presentation of monkeypox, again, prior to this cohort in 2022, was an incubation period of 5 to 20 days, followed by about 1 to 4 days of flu-like syndrome, and then the appearance of the rash. The rash starts with macules, turns to papules, [then] turns to vesicles, and turns to pustules, and then eventually ulcerates. It is predominantly more [evident] on the face and less so on the trunk, but it can involve the entire body, including the genitals. Generally the mortality is relatively low from that. [According to] West African data it is ~3%, although those data are much more skewed among populations that have higher levels of malnutrition, poorer health-seeking behaviors, etc.

In this new era in 2022, much of it is being described as genital lesions. So, penile lesions, intra-anal lesions, oral lesions, labial lesions around the lips. So, again, atypical presentations may also be a part of this new monkeypox pandemic... this endemic, and really emphasizing that the sexual and contact route may be an important part of transmission here.

Roman Jaeschke: What do you think we do not know yet? Where would be the effort of research or the epidemiological community going out?

Zain Chagla: I think there are big questions in terms of how long this has really been circulating, particularly as, again, there could have been a miss for this as some other genital ulcer disease. So, it may have been here for weeks and people may have been attributing it to another cause until someone finally made the diagnosis. The first reports were from the United Kingdom, and then rapidly cohorts of atypical genital ulcer disease have been identified in other countries.

I think we also need to understand how much immunity is left in our populations. One of the things that may be preventing large-scale monkeypox dissemination is the cross-reactivity of the smallpox vaccination. But at the same time, in Canada, we stopped smallpox vaccination around the 1970s, so that the cohort under the age of 50 may not have immunity at all. So, there would be some opportunities to see exactly what the seroprevalence is in those populations, especially as this may have been circulating for a couple of months before we discovered it.

I think there is a lot of work to be done on how to reach populations appropriately, knowing that if it is sexually acquired, [it] comes with the stigma that comes with sexually-acquired illnesses; especially, you know, knowing about HIV, particularly in this population, and some of the efforts that were very discriminatory in that population. So, how to apply that knowledge into a very hassle-free, safe approach for individuals to get tested and [for] postexposure prophylaxis to be given to high-risk contacts.

Roman Jaeschke: Thank you for this information, Zain. Is there any treatment for this condition once you get it?

Zain Chagla: The vast majority of cases are benign, have self-resolving outcomes, and do not require specific treatment. There are a couple of antivirals that have been used in poxviruses. There were older drugs like cidofovir or brincidofovir, which in more contemporary data probably do not have the activity and a large side-effect profile to support their use. The mainstay of treatment is an antiviral named Tecovirimat. This is available through our public health stocks as part of our pandemic planning for smallpox resurgence. It does show activity in vitro against the virus; in in vivo trials [it is] obviously not necessarily as high in the context of very little monkeypox activity over the last 10 years, but it is available for patients who have severe disease presentation. Again, one of the more important things is postexposure prophylaxis, so, people who are exposed to the virus, [those] who are at high risk. The concept of vaccination, which has been used for decades in smallpox as well as for monkeypox, can also be an effective strategy here. So, people who have a high-risk contact with someone who has monkeypox may be offered a vaccine to smallpox, which then decreases the risk of having symptomatic monkeypox, which then decreases the risk of downward transmission, also preventing them from getting severe disease as well.

Roman Jaeschke: So, despite the fact that we do not know all about this disease, the general level of anxiety, which I sensed a few weeks ago, is probably decreasing, probably because of both smallpox vaccination, which some of us are lucky to have, and then the potential availability of treatment and potential ability to limit transmission to some degree.

I would consider it our preliminary talk on monkeypox. I hope we will talk again, not necessarily too fast, because it would indicate some crisis. But thank you very much for the time and thank you for your expertise.

Zain Chagla: No problem. All the best.

English

English

Español

Español

українська

українська