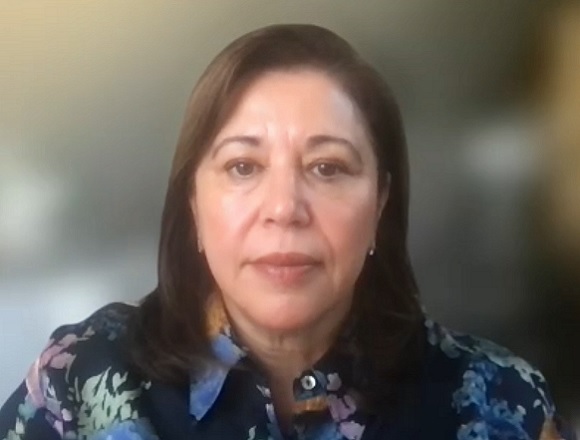

Sharon Kolasinski, MD, is a professor of clinical medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Pennsylvania, USA. As Chief of the Division of Rheumatology at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center and Director for Rheumatology at the Penn Musculoskeletal Center, she is responsible for coordination of inpatient and outpatient rheumatology services.

What’s the evidence on the efficacy of intra-articular injections of platelet-rich plasma (PRP)?

Sharon Kolasinski, MD: Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is an interesting therapy. This is a substance that is made from the patient’s own blood. A practitioner/provider will extract the patient’s blood, centrifuge it, get rid of the red blood cells, and then have a supernatant that may have a variable number of white blood cells in it. Low-leukocyte PRP is made, regular white blood cell PRP is made—different practitioners have different ideas about whether it’s good to have white blood cells or not good to have white blood cells in the mix, but there’s always some. The preparation is then reinjected back into the patient with the idea that your own body has healing substances, anabolic factors, growth factors that may be activated in the process and may also be beneficial to you and that are unlikely to cause an allergic reaction or an adverse reaction since they are from you.

The issue with studying an intervention like this is that every person is different, so we cannot be 100% sure (a) what is in any individual PRP preparation, and also (b) how they differ from one individual to the next. So, is my PRP the same as your PRP? Not sure, I don’t know. We don’t test those preparations prior to injecting them. The ease with which these preparations can be made and the sort of intuitive appeal of such a benign-seeming therapy has in part led to their popularization. And they’ve been used particularly in sports medicine, where many high-profile athletes have reported that they got great relief from PRP injections, so they have become popularized.

In osteoarthritis, they have not been broadly studied. The studies that have been done have been interesting. Many of them have compared PRP injections to hyaluronic acid injections. Now, hyaluronic acid injections are a somewhat controversial treatment that’s been around for decades, and really the bulk of high-quality data and meta-analyses suggest it is no better than placebo. So, it is interesting that many investigators have chosen hyaluronic acid as the control in most of the studies done. I think that this is in part because a similar audience might be interested in injectable therapies, either hyaluronic acid or PRP, so that may be part of why it’s so popularly compared. But interestingly, we would expect hyaluronic acid to be relatively ineffective. PRP, when compared with hyaluronic acid, has performed slightly better in trials that have been performed. Many of these have been very short term, and interestingly, the most end points have been negative for a comparison between PRP and hyaluronic acid. Some studies have shown delayed benefits in pain, which is not entirely intuitive and may be in part related to the fact that hyaluronic acid injections are given once every 6 months, but PRP injections may be given over and over, and over again. It’s hard to know if there is a blinding problem in studies that were done with multiple injections. So, in osteoarthritis, apart from the sports medicine interventions with PRP, we really don’t have adequate data to support the routine use of PRP intra-articularly.

English

English

Español

Español

українська

українська