Internal Medicine Rapid Refreshers is a series of concise information-packed videos refreshing your knowledge on key medical issues that general practitioners may encounter in their daily practice. This episode goes over the key points to remember about cellulitis.

Contents

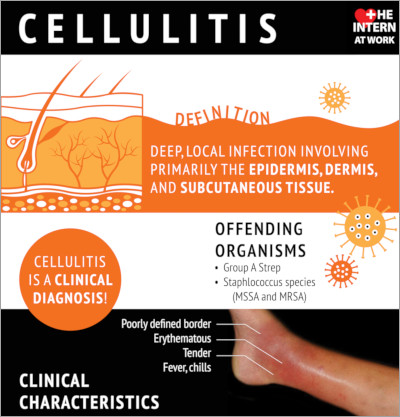

Infographic

Click to view the full image.

Infographic courtesy of The Intern at Work (theinternatwork.com).

Useful links

- Chapter on cellulitis from the McMaster Textbook of Internal Medicine

- Podcast on cellulitis from The Intern at Work

- 2014 practice guidelines for skin and soft tissue infections by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)

Transcript

Introduction

I’m Hosay Said, a senior medical resident at McMaster University. In this video we will go through a practical approach to the assessment and management of cellulitis. This video is intended for physicians returning to general internal medicine during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Overview

Cellulitis is a skin and soft tissue infection typically involving the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissues. It is classically characterized as a poorly demarcated, erythematous, hot, painful rash that most commonly involves a lower extremity, although it can occur anywhere. It can be associated with lymphangitic streaking or regional lymphadenopathy.

Approach

In the assessment of a patient with cellulitis, it is important to consider the following questions.

- Is this cellulitis or can it be something else?

- What are the patient’s specific risk factors for developing cellulitis?

- What is the most likely microbiology?

- What is the severity of the presentation? What life-threatening or limb-threatening diagnoses can’t you miss?

1. Differential diagnosis for cellulitis: When assessing a patient with a red, hot, swollen extremity, it’s important to think about alternative diagnoses, such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), chronic venous stasis or stasis dermatitis, gout, or septic arthritis.

2. Risk factors predisposing to cellulitis: Disruption to the skin barrier (abrasion, open skin wound), peripheral edema or lymphedema, chronic venous insufficiency, obesity, diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, and web space abnormalities or onychomycosis.

3. The most likely microbiology: The most common causative organisms for cellulitis are Staphylococcus aureus (including both methicillin-resistant S aureus [MRSA] and methicillin-susceptible S aureus [MSSA]) and beta-hemolytic streptococci (typically group A streptococcus).

Other organisms should be considered in specific circumstances. For example, Pseudomonas should be considered in patients who have diabetes and a chronic open wound, wet or macerated wound, recent nail trauma, or puncture wound. Cat or dog bites increase the risk of Pasteurella, Capnocytophaga, or polymicrobial infections, including anaerobes.

Consider risk factors for resistant organisms, specifically MRSA. These include residing in a long-term care facility, being on hemodialysis, prior known MRSA colonization, injection drug use, or recent hospitalizations.

It’s often helpful to look back at the patient’s old wound swabs to provide guidance as to whether they have specific or resistant organisms.

4. Severity: Grading the severity of cellulitis is helpful in the decision-making process and helps you decide who can be discharged home with oral antibiotic therapy and who needs to be admitted to the hospital for close monitoring and possibly intravenous (IV) antibiotics.

The systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria are a useful tool in categorizing the severity of cellulitis. The SIRS criteria are met in patients with ≥2 of the following: temperature >38 degrees Celsius or <36 degrees Celsius; heart rate >90 beats/min; respiratory rate >20 breaths/min; white blood cell (WBC) count >12,000/microL or <4000/microL. Classifying the severity based on a hot, red, angry-looking leg is not enough.

The severity can be categorized as mild, moderate, or severe. Mild infection refers to patients who are systemically well. Moderate infection describes patients who meet the SIRS criteria. Severe infection refers to patients who have failed oral antibiotic therapy and/or incision and drainage (I&D), which would represent source control; have systemic signs of infection or hypotension; are immunocompromised (eg, on chemotherapy, after organ transplantation); or have clinical signs of a deeper-seated infection.

Life-threatening/limb-threatening diagnoses you can’t miss: In the back of your mind always consider life-threatening or limb-threatening diagnoses: necrotizing fasciitis, toxic shock syndrome, and ischemic limb.

If your patient has a rapidly progressive cellulitis over the course of hours, evidence of hemodynamic instability, pain out of proportion to clinical examination findings, or any obvious skin changes (eg, crepitus, bullae, skin necrosis), necrotizing fasciitis must be considered. One of the things that can increase your clinical suspicion is the presence of sensory deficits, or a woodened, hardened characteristic to the subcutaneous tissue. These changes can precede the skin necrosis and therefore can be helpful in making you suspect necrotizing fasciitis more strongly.

It is important to remember that necrotizing fasciitis is a clinical diagnosis and surgical emergency. Urgent surgical consultation is required.

Think about toxic shock syndrome if your patient has profound hypotension, fever, and evidence of multiorgan failure.

If your patient has a cold limb with diminished or absent peripheral pulses, ischemic limb should be considered.

In patients with necrotizing fasciitis or toxic shock syndrome, intensive care unit (ICU) admission is likely required. Urgent surgical consultation should be obtained for necrotizing fasciitis, septic arthritis, and ischemic limb.

Investigations

Investigations that should be performed when a patient with cellulitis comes to the emergency department are a complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, and creatinine, looking for leukocytosis or acute kidney injury (AKI). A deep wound swab from open wounds may be helpful in identifying specific organisms. If the patient is septic or systemically unwell, 2 sets of blood cultures should be obtained before starting antibiotics.

Depending on your clinical impression of the patient, there are further investigations that you can order. If you have some suspicion of necrotizing fasciitis, consider x-ray of the limb, looking for evidence of subcutaneous air. But keep in mind that necrotizing fasciitis is a clinical diagnosis and a normal x-ray will not exclude it.

If you are suspecting necrotizing fasciitis or toxic shock syndrome, you can add creatine kinase (CK), looking for myositis, as well as these additional investigations to look for evidence of multisystem organ failure or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC): venous blood gas (VBG), lactate, liver enzymes/function tests, international normalized ratio (INR)/partial thromboplastin time (PTT), fibrinogen.

If you are suspecting DVT or an abscess, consider ultrasonography.

Management

We’re going to focus primarily on patients with moderate to severe infections, because they are likely to be referred to internal medicine and admitted to the hospital.

Remember that there’s always a physician available in the hospital or at home. Feel free to call them if you require any sort of assistance.

With every patient that you assess, check their airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC); obtain IV access; and initiate fluid resuscitation if they’re hypotensive. Because we’re likely going to be administering antibiotics, ask the patient about any potential allergies.

For typical cellulitis, without risk factors for resistant organisms, it’s appropriate to start antibiotic therapy using cefazolin 1 to 2 g IV every 8 hours. If the patient has MRSA risk factors, consider starting vancomycin 15 to 20 mg/kg IV every 12 hours, assuming the patient has normal renal function. If you have any concerns, you can always contact the pharmacist on call to clarify dosing.

Broader-spectrum antibiotics, like piperacillin/tazobactam, should be initiated in patients with risk factors for a more complicated or polymicrobial infection.

Cellulitis can often look worse before it looks better. For this reason, you should try using other indicators for tracking response to treatment, such as resolution of systemic infections (eg, fever, tachycardia) and at least improvement in pain.

If there is no improvement or ongoing worsening of findings after 48 to 72 hours of antibiotics, consider the possibility of an abscess or a bug-drug issue (eg, resistance or alternative microbiology), which would require a change in antibiotic therapy.

Typical treatment duration is 5 to 10 days, depending on clinical response.

If you are concerned about necrotizing fasciitis, it’s important to start empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics and make the necessary consultations with the ICU, appropriate surgical services, and infectious diseases. Empiric antibiotic therapy should include piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g IV every 8 hours + vancomycin with a loading dose of 25 to 30 mg/kg × 1 followed by 15 to 20 mg/kg every 12 hours (maximum, 2 g per dose) + clindamycin 600 to 900 mg IV every 8 hours.

Keep in mind that this is a surgical emergency that requires debridement.

Credits

I’d like to thank my coauthors: Doctor Heather Bannerman (postgraduate year 3 [PGY3] internal medicine resident; editor for this video) and Doctor Nishma Singhal (Division of Infectious Diseases; consultant for this video).

Resources used to create this Rapid Refresher include The Intern at Work infographics and podcasts as well as the 2014 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines for skin and soft tissue infections.

English

English

Español

Español

українська

українська