Internal Medicine Rapid Refreshers is a series of concise information-packed videos refreshing your knowledge on key medical issues that general practitioners may encounter in their daily practice. This episode outlines the essential points to keep in mind when managing syncope.

Contents

- Introduction

- Definition

- Assessment

- Physical examination

- Investigations

- Management

- Driving guidelines

- Credits

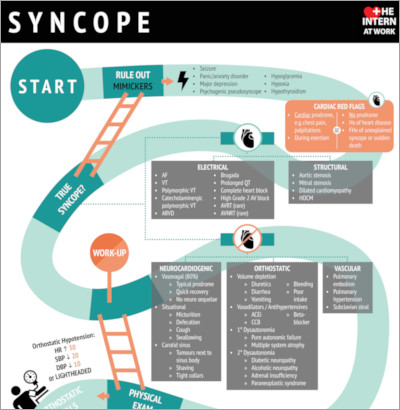

Infographic

Click to view the full image.

Infographic courtesy of The Intern at Work (theinternatwork.com).

Useful links

- Chapter on syncope from the McMaster Textbook of Internal Medicine

- Canadian Syncope Risk Score at mdcalc.com

- Assessment of the cardiac patient for fitness to drive and fly from the 2003 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Consensus Conference

Transcript

Introduction

I’m Heather Bannerman, a senior medical resident at McMaster University. This Rapid Refresher video will describe a practical approach to syncope. It is targeted to independently practicing physicians who are returning to general internal medicine and want to brush up on their knowledge. This is not meant to serve as medical advice to the general population.

Definition

Syncope is defined as a transient loss of consciousness caused by global cerebral hypoperfusion. It has a rapid onset, short duration, and spontaneous recovery without neurologic deficits.

Assessment

The first step when assessing a patient who presents with loss of consciousness is to consider symptoms that may mimic syncope and exclude them where possible. Mimickers include conditions with a loss of consciousness but where the loss of consciousness is due to a metabolic or structural abnormality rather than global cerebral hypoperfusion. This occurs in the case of seizures, hypoglycemia, hypoxia, hyperventilation with hypocapnia, and intoxication. Mimickers also include conditions that are not associated with a loss of consciousness but which occur suddenly, such as a fall or psychogenic pseudosyncope (appearance of a transient loss of consciousness in the absence of true loss of consciousness).

Once these mimickers are ruled out, causes of true syncope can be divided into 2 major categories: cardiac etiology and noncardiac etiology.

In order to get an accurate history of the syncopal event, the following questions should be asked:

- What happened leading up to the syncopal event (any triggers, any prodromal symptoms)?

- What happened during the syncopal event if there were witnesses? Seizure-like activity? Incontinence? Tongue-biting?

- What happened after the patient regained consciousness? Were they alert and oriented immediately or was there a period of drowsiness, suggesting a possible postictal state?

After gathering a comprehensive history, you need to consider features suggestive of a cardiac etiology. Cardiac syncope can be divided further into electrical and structural causes. Electrical causes include tachyarrhythmias (eg, ventricular tachycardia) or bradyarrhythmias (eg, complete heart block). Structural causes include severe aortic stenosis, mitral stenosis, dilated cardiomyopathy, or hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM).

Red flags on history which may point to a cardiac cause of syncope are (1) cardiac prodrome (eg, chest pain, shortness of breath, or palpitations); (2) syncope that occurs during exertion; (3) lack of prodrome entirely; (4) a history of heart disease; (5) a family history of unexplained syncope or sudden death.

Noncardiac (noncardiogenic) syncope can be divided into neurocardiogenic, orthostatic, and vascular etiologies. Neurocardiogenic causes of syncope include vasovagal, situational (eg, during urination or defecation), or carotid sinus stimulation. To further delineate these etiologies, a careful history is very important. For example, vasovagal syncope tends to have a prodrome, has a quick recovery, and has no neurologic sequelae. It may be associated with crowded spaces, prolonged standing, or emotional stress. Orthostatic syncope can be due to many underlying issues (volume depletion, vasodilators/antihypertensives, dysautonomia) and should be associated with positional changes. In terms of vascular etiologies of syncope, pulmonary embolism should always be on the initial differential diagnosis.

Physical examination

When conducting a physical examination for syncope, you should always measure the vital signs first. While getting vitals, make sure to also get orthostatic vitals in all syncopal patients. If the patient’s heart rate increases by >30 beats/min, their systolic blood pressure (SBP) decreases by >20 mm Hg, their diastolic blood pressure (DBP) decreases by >10 mm Hg, or they become lightheaded within 3 minutes of standing, they have orthostatic hypotension.

Other important physical examination maneuvers to complete in order to assess for a cardiac cause of syncope include listening for abnormal heart sounds or murmurs. Make sure to assess for any signs of venous thromboembolism (suggesting a possible pulmonary embolism), such as unilateral leg swelling, pain, or erythema.

It is also important to complete a neurologic examination, as any new focal neurologic deficits would point you towards investigating for stroke or seizure.

Investigations

To assess for cardiac syncope, make sure to get an electrocardiogram (ECG). Look for any signs of an underlying arrhythmia and for widening of the QRS complex, PR prolongation, an abnormal axis, or a prolonged QT interval (QTc). With the information gathered during the history, physical examination, and by looking at the ECG, you can use the Canadian Syncope Risk Score (linked above) to risk stratify patients and determine whether they are at high risk for a serious adverse event within the next 30 days. This risk score is validated for patients presenting to the emergency department with syncope.

You should also get a basic bloodwork (blood testing) panel including a complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, capillary blood glucose, and creatinine to assess for any metabolic disturbances that may be contributing to the patient’s presentation. A troponin level is also often needed, particularly if the patient presents with any chest pain or dyspnea with their syncopal episode. The remainder of the bloodwork should be based on the history and physical examination.

Management

If the patient is considered low risk according to the Canadian Syncope Risk Score and there are no other concerning features on history, physical examination, or investigations, they can likely be discharged home with no further work-up.

However, if they are medium to high risk, they will likely require a hospital admission for further work-up. This work-up should be based on the history and physical examination, but it may include an echocardiogram or cardiac monitoring. Depending on the most likely cause of the syncopal event based on history, physical exam, and investigations, the patient may also be sent for tilt table testing in the case of orthostatic hypotension, an electrophysiologic study in the case of arrhythmia-related cardiac syncope, or an electroencephalogram (EEG) in the case of possible seizures.

Driving guidelines

The following driving guidelines are based on the Canadian Cardiovascular Society 2003 consensus statement. If you are practicing elsewhere, you will need to consider your local laws and regulations.

After a single vasovagal syncopal event, the patient can continue to drive if the event did not occur while seated. If the patient has recurrent or unexplained syncope, you will need to file a report to the Ministry of Transportation and the patient will be unable to drive until they are syncope-free for 3 months (private drivers) or 12 months (commercial drivers).

Credits

I’d like to thank my coauthor, Doctor Akbar Panju (Division of Internal Medicine; consultant for this video).

The resources used during the creation of this Rapid Refresher were the McMaster Textbook of Internal Medicine, The Intern at Work podcasts and infographics, the Canadian Syncope Risk Score, and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) 2003 consensus statement regarding driving. All links to these resources are posted above.

Thank you for watching this Rapid Refresher video on syncope.

English

English

Español

Español

українська

українська