Montero-Odasso M, Van Der Velde N, Martin F, et al. World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age Ageing. 2022 Sep 2;51(9):afac205. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afac205. PMID: 36178003; PMCID: PMC9523684. Erratum in: Age Ageing. 2023 Sep 1;52(9):afad188. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afad188. Erratum in: Age Ageing. 2023 Oct 2;52(10):afad199. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afad199.

Seppala LJ, Petrovic M, Ryg J, et al. STOPPFall (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in older adults with high fall risk): a Delphi study by the EuGMS task and finish group on fall-risk-increasing drugs. Age Ageing. 2021 Jun 28;50(4):1189-1199. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa249. PMID: 33349863; PMCID: PMC8244563.

Ganz D, Latham NK. Prevention of Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 20;382(8):734-743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1903252. PMID: 32074420.

Guirguis-Blake JM, Michael YL, Perdue LA, Coppola EL, Beil TL. Interventions to prevent falls in older adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018 Apr 24;319(16):1705-1716. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21962. PMID: 29710140.

Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons, American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society. Summary of the Updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011 Jan;59(1):148-57. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03234.x. PMID: 21226685.

Stinchcombe A, Kuran N, Powell S. Report summary. Seniors’ Falls in Canada: Second Report: key highlights. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2014 Jul;34(2-3):171-4. PMID: 24991781.

Ganz D, Bao Y, Shekelle PG, Rubenstein, LZ. Will my patient fall? JAMA. 2007 Jan 3;297(1):77-86. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.1.77. PMID: 17200478.

A fall is defined as a sudden and unintentional event in which an individual comes to rest on the ground, floor, or at a lower level than previously. Falls have a major impact on morbidity, mortality, and health care spending. They are the second leading cause of unintentional injury-related deaths in the world. In Canada falls cause 95% of all hip fractures and account for CAD $2 billion in direct health care costs per year. It is estimated that 20% to 30% of individuals aged ≥65 years experience ≥1 fall each year. Falls have significant physical and mental health implications for older adults, leading to the fear of falling, immobilization, isolation, depression, delirium, loss of independence, and transition to long-term care.

Falls are often labeled as “mechanical falls” in the clinical setting. However, this designation implies that the fall was solely due to an external and nonmodifiable force, such as slipping and falling on an icy surface. In reality the factors leading an individual to fall are much more nuanced, and falls should not be dismissed as mechanical without consideration and adequate assessment of modifiable risk factors. For example, vision impairment may result in the inability to identify an icy surface ahead, and balance impairment may prohibit the individual from catching themselves. The term mechanical fall is therefore discouraged.

To understand how individuals fall, it is important to have a basic understanding of normal gait. This is a complex skill requiring coordination and optimal functioning of one’s neurologic and musculoskeletal systems. Higher brain centers provide instructions for the timing and positioning of one’s limbs in space, as well as information for loading and unloading the body’s weight during normal gait. Postural reflexes are then involved in adjusting the trunk and limbs with each shift in support surface to maintain balance. These reflexes rely on input from the visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems. Moreover, cognitive function and attention are important for choosing a path and mitigating obstacles along that path. Thus, normal gait relies on the smooth integration of cognition, processing, neuronal networks, and musculoskeletal strength and tone.

With aging, various parts of this complex system change. For example, sensory input is diminished from visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems and postural reflexes are slower. In addition, there are changes in blood pressure regulation as we age, due to reduced vascular compliance and baroreflex sensitivity, which may increase the risk of orthostasis in older adults. Of note, disordered gait is not necessarily a component of natural aging and normal gait is maintained in many older adults.

Screening and Risk Stratification

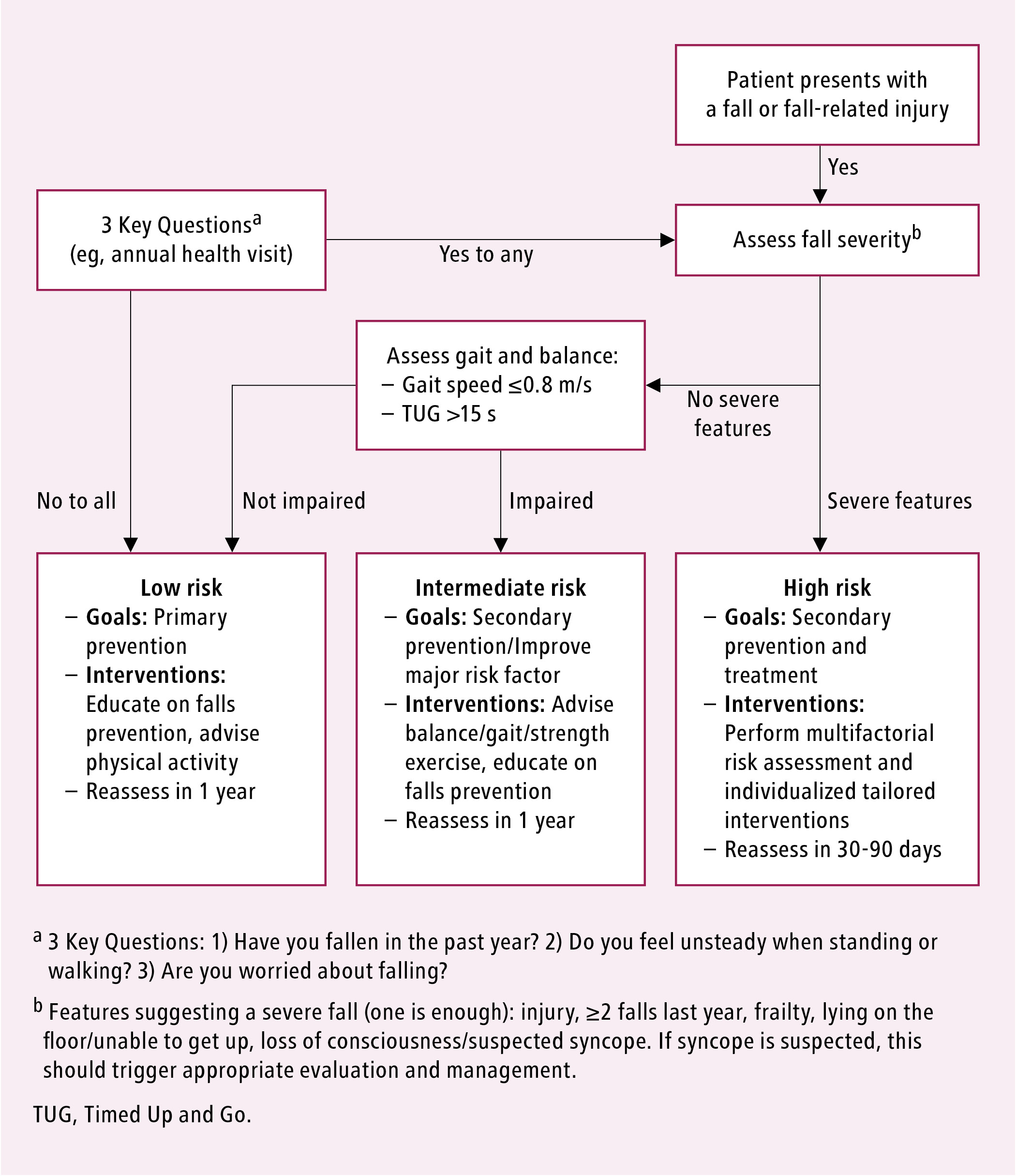

The 2022 World Guidelines for Falls Prevention and Management recommend stratifying older adults into low-, intermediate- and high-risk-of-fall categories. Risk stratification is recommended either after opportunistic case finding, such as during routine health checkups or through electronic health records, or when patients present with a fall or fall-related injury. Although the single question of “Have you fallen in the last 12 months?” can be used to assess falls risk, a more sensitive tool such as the 3 Key Questions (3KQ) can be used to assess for >1 fall risk factor in adults >65 years:

1) Have you had any falls in the past 12 months? If so, how many?

2) Do you have any unsteadiness when standing or walking?

3) Do you have fears about falling?

Negative answers to all the 3 questions identify those at low risk of falling, while a positive answer to any should trigger the assessment of fall severity, with any of the following features placing the patient in the high-risk-of-falls category:

1) Injury.

2) At least 2 falls last year.

3) Frailty (Clinical Frailty Scale ≥4).

4) Lying on the floor and being unable to get up for >1 hour.

5) Loss of consciousness or suspected syncope.

Of note, syncope should also be considered as a cause of falls and evaluated accordingly.

If the patient does not fit into the high- or low-risk category, the next step is to evaluate for gait or balance impairment using one or a combination of the screening tools:

1) Gait speed:

a) Components: This test requires the patient to walk a prespecified distance (eg, 4 m) and involves timing the speed of walking. Walking speed should be allowed to reach a steady state for accurate measurement.

b) Scoring: A speed <0.8 m/s (taking >5 s to walk 4 m) predicts frailty and falls.

2) Timed Up and Go (TUG):

a) Components: This test involves timing how long it takes for a patient to stand up from a standard-height armchair, walk 3 meters, turn around, walk back to their chair, and sit down again. The patient is to use their usual walking aid and footwear, without additional physical assistance. Their back must be up against the back of the chair prior to starting. They are to walk at their usual pace. The patient is first allowed to walk through the test using their walking aid to become familiar with it before being timed.

b) Scoring: A time >15 seconds has been shown to be associated with a high risk of falls.

Additional tools, each requiring several minutes to perform, include the Berg Balance Scale (BBS), Tinetti Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment (POMA), and Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).

In comparison with other risk factors for falls, gait and balance more frequently predict future falls. Therefore, even in the absence of high-risk features, the presence of gait and balance impairment alone places patients in the intermediate-risk category.

After completing the assessment, patients who are considered at low risk of falling should receive education on falls prevention and advice on physical activity. Patients at intermediate and low risk should be reassessed in 1 year. Those at high risk should undergo a multifactorial assessment and physical examination: Risk Factors, Prevention, and Intervention.

Risk Factors, Prevention, and Intervention

Assessment of Falls in Community-Dwelling Patients

Algorithm for risk stratification, assessment, and management in community-dwelling older adults: Figure 8.1-1.

After identifying community-dwelling patients at the highest risk, guidelines highlight a multifactorial, multidisciplinary intervention as the most effective method of falls prevention. In a multifactorial intervention, participants are offered a customized set of interventions that target specific risk factors. Identified through assessment, risk factors can be categorized as intrinsic or extrinsic (Table 8.1-1). Of note, simply identifying the risk factors without direct intervention is not effective. As carrying out a multifactorial assessment and subsequent interventions can be a time-intensive process, it is advisable to compartmentalize the process into several visits, with the order of interventions based on risk factors identified during the assessment that are most concerning to the patient or caregivers or pertinent.

Assessment of Falls in Hospital

In comparison with the ambulatory setting, the assessment of an acute fall may be more challenging due to time constraints and lack of follow-up. Therefore, emphasis is put on identifying red flags, immediate injuries, and high-risk patients for referral for further assessment in an ambulatory setting. The available multidisciplinary resources may differ by hospital.

1. History:

1) Circumstances of the fall:

a) Circumstances around the fall (eg, tripping over something in the environment).

b) Associated symptoms (eg, lightheadedness).

c) Presence of syncope: see Syncope.

d) Complications due to the fall itself (eg, fractures, head injury) or complications due to prolonged time on the ground—especially in patients assessed in an emergency department (rhabdomyolysis, dehydration).

2) Assessment of acute medical illness that may have accounted for the fall:

a) Vestibular dysfunction (eg, dizziness or “room spinning”).

b) Arrhythmias (eg, palpitations).

c) Cerebrovascular disease (eg, asymmetric weakness, change in speech or vision).

d) Seizure (eg, abnormal body movements, tongue biting, or incontinence).

3) Past medical history: Conditions that might increase the risk of falls (eg, Parkinson disease, dementia, stroke, osteoarthritis), history of osteoporosis and the associated risk of fracture.

4) Medications: Medications that might increase the risk of falls (Table 8.1-2), any osteoporosis treatment.

5) Screening questions: Questions as outlined in the previous section can help identify older adults at high risk of future falls and direct appropriate referrals from the acute setting.

2. Physical examination:

1) Vitals, including orthostatic vital signs.

2) Gait assessment, use of gait aids, footwear: Assessing gait for elements such as movement initiation, stride length and width, symmetry, posture, arm swing, and turning.

3) Cardiac, respiratory, and abdominal examination: Any acute medical illness that might contribute to falls presentation or the presence of risk factors for syncope (eg, severe aortic stenosis or severe volume depletion).

4) Neurologic examination: Assess for any focal deficits; peripheral neuropathy; or hearing, vision, and cognitive impairment.

5) Musculoskeletal examination: Any associated injuries or evidence of significant osteoarthritis.

3. Investigations: Further investigations including laboratory testing and imaging should be guided by a suspicion of acute medical illness and any subsequent injuries. For minor head injuries use the Canadian Head CT Rule (mdcalc.com) to guide the decision on imaging. This tool identifies high- and moderate-risk features associated with clinically important injury, which may require admission to hospital, neurologic follow-up, or neurologic intervention; note that the rule does not apply if the patient is on therapeutic anticoagulation.

4. High-risk features: Glasgow Coma Scale <15 at 2 hours post injury, suspected skull fracture, any sign of basal skull fracture, ≥2 episodes of vomiting, or age ≥65 years.

5. Moderate-risk features: Amnesia before impact ≥30 minutes or a dangerous mechanism of the fall (a pedestrian struck by a motor vehicle, occupant ejected from a motor vehicle, fall from >3 feet or >5 stairs).

Further physical examinations and investigations specific to each falls risk factor: Table 8.1-1.

Prevention of Complications of Falls

1. Preventing fractures:

1) Hip protectors: There is insufficient evidence to suggest the use of hip protectors to prevent hip fractures from falls, potentially because they are often not worn or that the injury occurs in circumstances where hip protectors would not have been worn. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated a small effect on hip fracture reduction with hip protectors in nursing home settings, but no evidence for their use has been established in the community setting.Evidence 1 Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias. Santesso N, Carrasco-Labra A, Brignardello-Petersen R. Hip protectors for preventing hip fractures in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Mar 31;2014(3):CD001255. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001255.pub5. PMID: 24687239; PMCID: PMC10754476.

2) Osteoporosis screening: Screening for osteoporosis has been found to reduce hip fracture incidence, and some practice guidelines suggest its use in all women aged ≥65 years.Evidence 2 Weak recommendation (suggestion), in favor: Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias. US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018 Jun 26;319(24):2521-2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7498. PMID: 29946735. Additionally, initiating osteoporosis pharmacologic therapy after a fracture has been shown to reduce the risk of subsequent fractures, which are often consequences of falls.

3) Assistive devices: There is no convincing evidence to support the hypothesis that the use of assistive devices, such as walkers or canes, prevents falls or their complications. Observational studies have in fact shown an increase in the risk of falls, potentially as those individuals who are most likely to use an assistive device already experience more significant alterations in gait and balance. It has also been suggested that the use of assistive devices may impair compensatory stepping and therefore increase the risk of falls.

2. Preventing bleeding:

1) Anticoagulation management: The risk of subdural hematoma from a fall in older adults taking anticoagulation may be increased by as much as 50%, but in most patients it does not appear to be large enough to outweigh the benefits of stroke prevention in situations of anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation.Evidence 3Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to modeling data. Man-Son-Hing M , Nichol G, Lau A, Laupaci A. Choosing antithrombotic therapy for elderly patients with atrial fibrillation who are at risk for falls. Arch Intern Med. 1999 Apr 12;159(7):677-85. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.7.677. PMID: 10218746.

3. Preventing prolongation of time on the floor:

1) Call alarm: Complications that arise from increased length of time on the floor after a fall—or “long lie”—include serious injury, hospital admission, and discharge location other than the patient’s own home. There is a theoretical benefit in the use of call alarm systems to enable patients to call for help and avoid a long lie. However, there is unclear evidence surrounding the utility of those systems in preventing the complications of falls as a standalone intervention, mostly due to lack of adherence.Evidence 4Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to observational data. Fleming J, Brayne C. Inability to get up after falling, subsequent time on floor, and summoning help: prospective cohort study in people over 90. BMJ. 2008; 337: a2227. Published online 2008 Nov 17. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2227. PMID: 19015185; PMCID: PMC2590903.

|

Risk factors and impairments |

Assessment |

Interventions |

|

Intrinsic |

||

|

Balance impairment: Underlying vestibular and somatosensory impairment, muscle weakness, and delayed reaction time |

Gait speed, TUG, BBS, Tinetti test (POMA), and SPPB (see Screening and Risk Stratification)

|

– Resistance, balance, gait, and coordination training (eg, sit to stand, stepping): Formal outpatient and home-based programs (eg, tai chi, group and home-based exercise programs, physiotherapy); ideally ≥3 times weekly for ≥12 weeks for the best effect – Mobility aids and assistive devices, eg, cane, wheeled walker

|

|

Gait impairment (gait speed <0.8 m/s): Difficulties in navigating obstacles or stairs |

||

|

Visual impairment: Contrast and depth perception

|

Check eye examination records in the past 1-2 years for new issues and use of multifocal lenses |

– Eye examinations every 1-2 years – Cataract surgery if indicated – Use of single-lens distance glasses when outdoors – Note that vision correction can paradoxically increase the risk of falls thought to be secondary to adjustment to new glasses |

|

Cognitive impairment: Impairment in the executive function domain (responsible for planning and self-regulation) |

Screen using Mini-Cog, MMSE, or MoCA |

– Adequate patient supervision during daily activities – Nonpharmacologic interventions for dementia preferred, as cholinesterase inhibitors are associated with increased risk of syncope |

|

Orthostatic hypotension: Transient cerebral hypoperfusion and subsequent loss of balance |

Assess orthostatic vital signs by measuring blood pressure and heart rate in the supine position after 5 minutes of bed rest, then in the standing position in 1-minute intervals for up to 5 minutes. If positive, assess for etiologies of orthostatic hypotension including medication review

|

– Medication review and consideration of deprescribing – Nonpharmacologic therapies such as adequate hydration, compression stockings, and abdominal binders – Pharmacologic treatment with fludrocortisone or midodrine, but evidence of benefit is lacking |

|

Depressive symptoms: Psychomotor retardation, loss of motivation and confidence to mobilize |

– Evaluate and treat for reversible causes such as hypothyroidism – Nonpharmacologic interventions are preferred given the potential increased risk of falls with antidepressants – Pharmacologic interventions should be considered after weighing risks and benefits |

|

|

Difficulties with ADL |

Assess basic activities of daily living, eg, with the Bristol ADL Scale |

– Home modification: see “Environmental hazards” below – Mobility aids and assistive devices, eg, cane, wheeled walker

|

|

Difficulties with IADL |

Assess instrumental activities of daily living, eg, with the Lawton-Brody IADL Scale |

|

|

Sarcopenia |

Assess grip strength with a dynamometer. Assess proximal muscle strength with the 30-second chair stand test, where a below-average number of stands for the age group in 30 seconds indicates a high risk of falls |

– Identify modifiable comorbidities such as osteoporosis, osteopenia, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus – Some evidence for resistance training and nutrition optimization with focus on protein intake |

|

Arrhythmias: May be reported as fall rather than syncope if patient is amnesic following the event |

A complete cardiovascular assessment is recommended including cardiac history, auscultation, orthostatic vitals, and a 12-lead electrocardiogram. Holter monitoring has no proven benefit as part of a routine falls assessment but can be done depending on clinical suspicion |

– Refer for cardiac evaluation – Cardiac pacing for treatment of bradyarrhythmia |

|

Urinary incontinence: Urge incontinence, stress incontinence, and nocturia |

Differentiate between the types of urinary incontinence using 3IQ

|

– Refer for urologic evaluation or to a specialized continence clinic – Nonpharmacologic management including continence products, timed toileting, bladder retraining, weight loss – Pharmacologic management differs depending on incontinence type |

|

Malnutrition |

Assess for adequate vitamin D intake, vitamin levels, substance use, excessive alcohol use, obesity, and sarcopenia. Screening tools such as MNA can be used |

– Lifestyle modification for foods rich in proteins and calcium – Recent evidence showed no benefit in falls reduction in community-dwelling older adults who did not have other indications for vitamin D supplementation. Therefore, vitamin D should only be prescribed for those at risk of deficiency |

|

Extrinsic |

||

|

Medications |

Assess for the use of medicines without a compelling indication and screen for FRIDs (table 8.1-2) using instruments such as STOPPFall

|

– Taper or discontinue medications that are not indicated or have greater harm than benefit – Encourage nonpharmacologic strategies to address certain conditions when applicable (eg, sleeping hygiene education and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia) |

|

Environmental hazards: At least 2 home hazards such as tripping hazards (rugs, electrical cords), slippery surfaces, and poor lighting |

Home-safety evaluation performed by a trained professional with follow-up for recommended modifications |

– Home modification such as removal of identified hazards and lighting improvements – Installation of adaptive equipment such as handrails and bathroom grab bars – Attention to hazards outside of home |

|

Foot health and footwear

|

Foot assessment looking for bunions, nail deformities, and ulcers; assess if footwear are ill-fitting, with worn soles, high heels, or not laced or buckled |

– Advice on appropriate footwear – Referral for appropriate treatment if issues are identified |

|

3IQ, 3 Incontinence Questions; ADL, activities of daily living; BBS, Berg Balance Scale; FRID, fall-risk–increasing drug; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MMSE, Mini–Mental State Examination; MNA, Mini Nutritional Assessment; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; POMA, Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment; PQH-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery; STOPPFall, Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in older adults with high fall risk; TUG, Timed Up and Go. |

||

|

Drug class |

Comments |

|

Alpha-blockers (used as antihypertensives) |

– |

|

Alpha-blockers (for prostate hyperplasia) |

Particularly nonselective alpha-blockers |

|

Centrally-acting antihypertensives |

– |

|

Vasodilators used in cardiac diseases |

– |

|

Antipsychotics |

Related to sedative, anticholinergic, and alpha-receptor properties |

|

Antidepressants |

– Particularly tricyclic antidepressants – Related to sedative and anticholinergic properties and tendency to cause orthostatic hypotension |

|

Antihyperglycemics |

Particularly sulfonylureas |

|

Antiarrhythmics |

– |

|

Anticholinergics |

– |

|

Antihistamines |

Particularly first-generation antihistamines, due to sedative and anticholinergic properties |

|

Antiepileptics |

Particularly older antiepileptics |

|

Sedatives-hypnotics |

– |

|

Opioids |

– |

|

Diuretics |

Particularly loop diuretics |

|

Medications for overactive bladder and urge incontinence |

Related to anticholinergic properties |

Figure 8.1-1. Algorithm for risk stratification, assessment, and management in community-dwelling older adults. Adapted with author’s permission from Age and Ageing. 2022 Sep 2;51(9):afac205.