Morin SN, Feldman S, Funnell L, et al; Osteoporosis Canada 2023 Guideline Update Group. Clinical practice guideline for management of osteoporosis and fracture prevention in Canada: 2023 update. CMAJ. 2023 Oct 10;195(39):E1333-E1348. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.221647. PMID: 37816527; PMCID: PMC10610956.

LeBoff MS, Greenspan SL, Insogna KL, et al. The clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2022 Oct;33(10):2049-2102. doi: 10.1007/s00198-021-05900-y. Epub 2022 Apr 28. Erratum in: Osteoporos Int. 2022 Oct;33(10):2243. doi: 10.1007/s00198-022-06479-8. PMID: 35478046; PMCID: PMC9546973.

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Harvey NC, Johansson H, Leslie WD. Intervention Thresholds and the Diagnosis of Osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2015 Oct;30(10):1747-53. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2531. Review. PMID: 26390977.

Kanis JA, Hans D, Cooper C, et al; Task Force of the FRAX Initiative. Interpretation and use of FRAX in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int. 2011 Sep;22(9):2395-411. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1713-z. Epub 2011 Jul 21. Review. PMID: 21779818.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Osteoporosis is a systemic disease of the skeleton characterized by an elevated risk of bone fractures due to decreased bone strength. Bone strength depends on the mineral density and architecture of bones.

A low-impact (fragility) fracture is defined as a fracture caused by a force that normally does not cause fracture of a healthy bone (fall from a standing height or a spontaneous fracture). The cause of a low-impact fracture may be other than osteoporosis and involve, for instance, cancer.

Primary osteoporosis is defined as bone loss that occurs during the natural aging process. Secondary osteoporosis results from various diseases or adverse effects of certain drugs, most frequently glucocorticoids.

Several fracture-risk stratification models, such as FRAX and FRAXplus, have identified clinical risk factors associated with osteoporosis and fracture risk. They include:

1) Age: Advanced age contributes to fracture risk.

2) Sex: Osteoporosis is 4 times more prevalent in women than in men.

3) Body mass index (BMI) <18 kg/m2.

4) Previous fracture: A fracture at the age >50 years or a fracture arising from trauma that would not have resulted in a fracture in a healthy individual.

5) Parental hip fracture.

6) Current smoking.

7) Glucocorticoid use for >3 months at a dose of ≥5 mg/d of prednisolone (or equivalent doses of other glucocorticoids).

8) Secondary osteoporosis: Disorders strongly associated with osteoporosis, including type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus, osteogenesis imperfecta in adults, untreated long-standing hyperthyroidism, hypogonadism or premature menopause (<45 years), chronic malnutrition or malabsorption, chronic renal failure (dialysis independent), and chronic liver disease.

9) Alcohol ≥3 units/d.

10) Recency of osteoporotic fracture: The risk of a recurrent fragility fracture is particularly high immediately following the fracture (up to 2 years).

11) High exposure to oral glucocorticoids: Dosages >7.5 mg/d increase the probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (MOF) by 15% and the probability of hip fracture by 20%.

12) Falls: A history of falls is correlated with an increased risk of hip fractures and MOFs. Factors contributing to the increased risk include immobilization, sarcopenia (loss of mass, strength, and function of skeletal muscles related to age or comorbidities), and frailty.

a) Frailty is a dynamic clinical condition characterized by increased vulnerability resulting from age-related degeneration in psychologic, physical, and social functioning. The fracture rate for frail adults in long-term care (LTC) is 2 to 4 times higher than that of those living in the community. Approximately one-third of older adults who experience hip fractures are residents in LTC (see Frailty).

b) Hip axis length (HAL): A longer than average HAL is associated with increased hip fracture risk.

Other risk factors include:

1) Genetic and demographic factors: White or Asian populations.

2) Reproductive factors: Deficiency of sex hormones (estrogen, testosterone) due to various etiologies, prolonged amenorrhea (late puberty, periods of estrogen deficiency), nulliparity, postmenopausal status (particularly premature, including patients after oophorectomy).

3) Nutrition and lifestyle factors: Low calcium intake (daily calcium requirements: children aged 1-10 years require ~800 mg elemental calcium; adolescents and adults, 1000-1200 mg; pregnant and breastfeeding women, postmenopausal women, and older individuals, 1200-1400 mg), vitamin D deficiency (causes: see Hypocalcemia), low or excessive phosphate intake, protein deficiency or excessive protein intake.

4) Coexisting conditions (these may lead to secondary osteoporosis):

a) Endocrinologic conditions: Hyperparathyroidism, Cushing syndrome (hyperadrenocorticism), thyrotoxicosis, acromegaly, diabetes mellitus, endometriosis, hyperprolactinemia, hypogonadism (primary or secondary), tumors secreting parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP), Addison disease.

b) Gastrointestinal (GI) conditions: Malabsorption syndromes (most frequently celiac disease), patients after gastrectomy or small intestine resection, patients after bariatric surgery, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis), chronic liver disease with cholestasis (particularly primary biliary cholangitis in women) or without cholestasis, total parenteral nutrition.

c) Renal conditions: Calcium-losing and phosphate-losing nephropathy, nephrotic syndrome, chronic kidney disease (CKD) (particularly in patients undergoing dialysis).

d) Rheumatologic conditions: Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriatic arthritis.

e) Lung diseases: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis.

f) Hematologic conditions: Multiple myeloma, myeloid leukemia, lymphoma, hemophilia, systemic mastocytosis, sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, amyloidosis.

g) Other: Sarcoidosis, vitamin A toxicity.

5) Drugs: Glucocorticoids, high doses of thyroid hormones, antiepileptic drugs (phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine), heparin (in particular unfractionated heparin), vitamin K antagonists, cyclosporine (INN ciclosporin), high doses of immunosuppressive agents and other antimetabolites, bile acid sequestrants (eg, cholestyramine), gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues, thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone), tamoxifen (in premenopausal women), sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, aromatase inhibitors, androgen deprivation therapy, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRIs), antiretroviral drugs.

DiagnosisTop

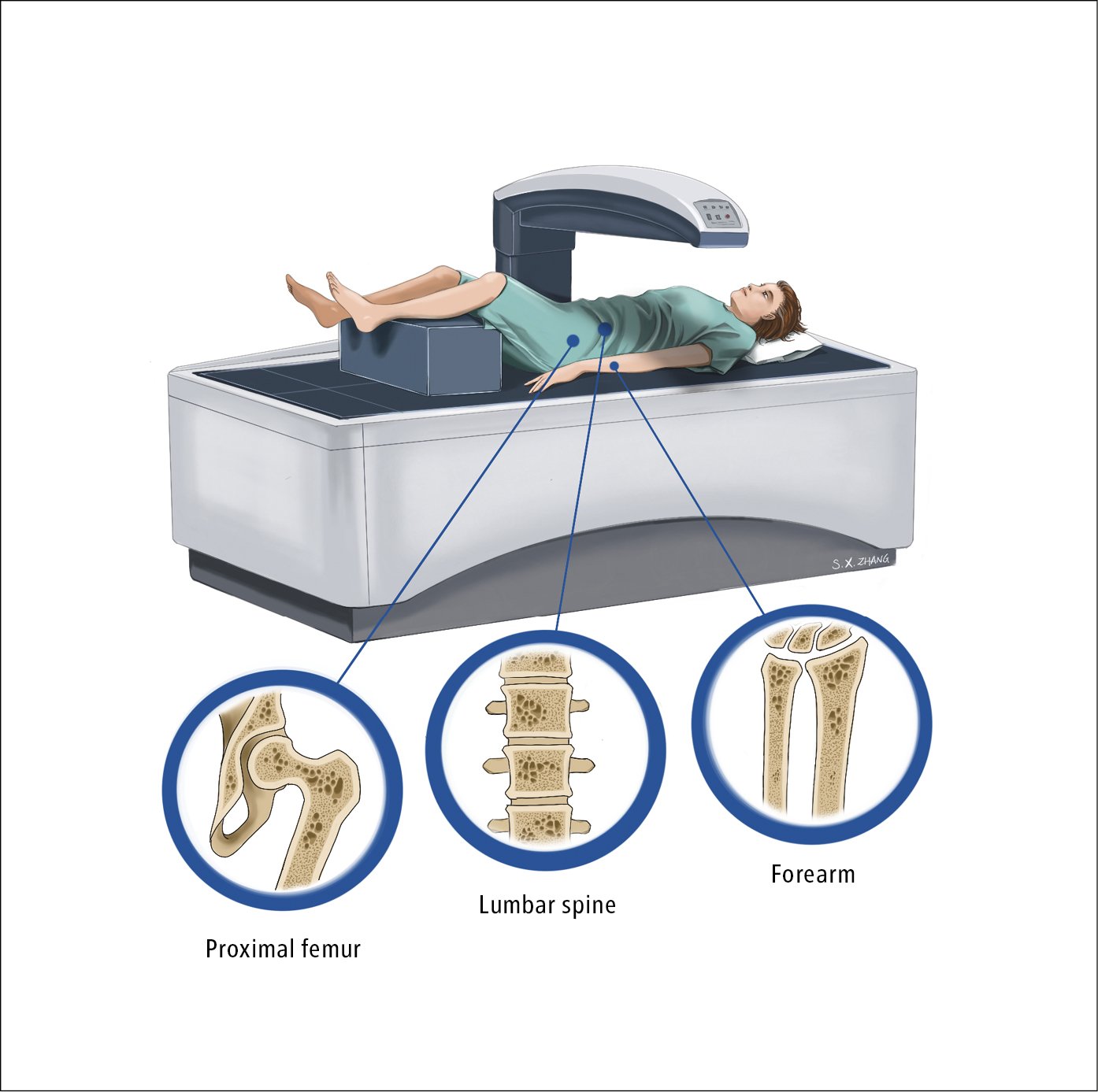

1. Bone densitometry measures bone mineral density (BMD). It is particularly indicated in patients at an increased risk of fractures but also used to monitor the disease and effectiveness of treatment (the risk of fractures can be estimated using the fracture risk assessment tool FRAX, a BMI risk calculator adjusted for country or population [available online from the University of Sheffield], and FRAXplus, an updated risk stratification model). The only recommended diagnostic method in osteoporosis is dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (Figure 18.15-1), which is used to measure:

1) BMD of the proximal femur (femoral neck, shaft, Ward triangle, or greater trochanter; results are given separately for all the 3 sites or for the entire proximal femur [so-called total hip BMD]).

2) BMD of the lumbar spine (L1-L4; anteroposterior view). A falsely elevated spine T score may be caused by fracture of a vertebral body (detected by measurement of the lumbar spine); advanced degenerative changes of the spine (including vertebral bodies and facet joints), for instance, in Forestier disease (diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis); significant atherosclerotic changes of the abdominal aorta; and calcification of spinal ligaments (eg, in AS).

3) BMD of bones of the forearm. Densitometry of the bones of the forearm may be done if measurement of the proximal femur or of the spine is not possible, if the results are difficult to interpret, and in patients with hyperparathyroidism.

4) Total body BMD. This measurement may be performed in children and in adults but tends to be reserved for special circumstances, such as measuring body composition.

Femoral neck and total hip BMDs are the recommended parameters for diagnosing osteoporosis, while fracture risk can be determined by combining the femoral neck and lumbar spine T scores.

A typical printout of DXA results contains an image of the examined site and results of the following measurements: BMD in g/cm2, T scores (standard deviation from values for healthy women aged 20-29 years), and Z scores (standard deviation from values for an age-matched and sex-matched reference population).

2. Imaging studies:

1) Conventional plain radiography has limited value in the assessment of osteoporosis, especially in the early stages of the disease. Plain radiographs will show decreased bone density if bone loss is >30% to 50%. Additional findings may include thinning of the cortex of long bones, loss of horizontal trabeculae, prominent supportive trabeculae, prominent laminae of vertebral bodies, and compression fractures. The technique used for detection and evaluation of fractures is radiographic morphometry. A compression fracture is defined as a decrease ≥20% in the height of the vertebral body at any level as compared with the posterior vertebral height in the thoracic or lumbar region in the lateral view. New guidelines recommend vertebral imaging with lateral spine radiography if patients have a MOF risk between 15% and 19% based on FRAX or are aged >65 years and have a T score ≤−2.5.

2) Vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) is a new technology using central DXA that permits imaging of the thoracic and lumbar spine to evaluate for the presence of vertebral fractures.

3) Trabecular bone score (TBS) is an indirect measure of bone structure derived from texture software developed for use with DXA. It is an independent predictor of fracture risk and has recently been incorporated into FRAX.

4) Quantitative computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are useful in selected patients, particularly those with secondary osteoporosis. They provide information on the underlying bone quality and microarchitecture on top of volumetric BMD provided by DXA assessment.

3. Laboratory tests:

1) Increased levels of biochemical markers of bone turnover (these are not recommended for establishing the diagnosis but may be used for additional estimation of fracture risk and monitoring treatment effects): N-terminal propeptide of type I collagen (PINP) for bone formation and cross-linked C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX) for bone resorption.

2) Abnormalities associated with an underlying condition in patients with secondary osteoporosis: Perform appropriate tests to exclude secondary osteoporosis, including complete blood count (CBC); serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) for patients with vertebral fractures; serum levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), creatinine, parathyroid hormone (PTH); 25(OH)D3 in those with risk factors for insufficiency; calcium corrected for albumin, and phosphate; as well as considering a 24-hour urinary calcium excretion (assessment of calcium and phosphate metabolism: see Calcium Disturbances, see Phosphate Disturbances).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria, osteoporosis is diagnosed based on low BMD of the femoral neck (in clinical practice values for the proximal femur or lumbar spine are also used), with a T score ≤−2.5 in postmenopausal women (T scores from −1.0 to >−2.5 are classified as osteopenia) and in men aged ≥50 years. In younger patients, additional risk factors are needed and usually secondary osteoporosis is diagnosed. DXA must include Z scores instead of T scores in patients with continued skeletal growth.

While osteoporosis is defined by BMD measurement, the risk for fracture uses BMD and a number of risk factors, many defined in FRAX. BMD assessment alone is not sufficient to identify fracture risk, as certain patients will be undertreated or overtreated if decisions are based on BMD values alone. Therefore, it is necessary to calculate the absolute 10-year risk of fracture based on risk factors present in the patient.

According to the WHO, the recommended tool for calculating individual risk in persons aged 40 to 90 years is FRAX (available from the University of Sheffield). The calculator takes into consideration the following 12 parameters: age, sex, weight, height, prior fractures, prior hip fractures in a parent, current tobacco smoking, current treatment with glucocorticoids (for >3 months in a dose equivalent to ≥5 mg/d of prednisolone), RA, secondary osteoporosis, alcohol intake (≥3 units/d), and, if available, BMD of the femoral neck. Because the calculator does not take into account several other risk factors, the threshold for intervention should be lower in patients with multiple prior fractures, long-term high-dose glucocorticoid treatment, high levels of biochemical markers of bone turnover, as well as sarcopenia or a history of frequent falls. In younger individuals, including premenopausal women, and in patients receiving pharmacologic treatment for osteoporosis, FRAX is not useful.

1. Congenital bone fragility (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta).

2. Osteomalacia.

3. Secondary osteoporosis:

1) Drugs: Glucocorticoids, SSRIs, SNRIs, aromatase inhibitors, PPIs, androgen deprivation therapy.

2) Inflammatory disorders: RA, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

4. Other metabolic bone disease:

1) Hyperparathyroidism.

2) Hyperthyroidism.

3) Cushing disease.

5. Malignancy:

1) Multiple myeloma.

2) Leukemia.

6. Chronic kidney and liver diseases.

TreatmentTop

1. The goal of treatment is to prevent fractures. Therapeutic interventions should have proven efficacy in fracture prevention and not just in the prevention of further loss of BMD.

2. Indications for pharmacotherapy:

1) Postmenopausal women and men aged ≥50 years who are considered to be at high risk for fracture based on FRAX (including low-impact fracture at any age). Those at moderate risk for fracture may be considered for therapy if additional fracture risk factors not used in FRAX are identified, such as falls or frailty.

2) In premenopausal women and men aged ≤50 years: A history of a low-impact fracture or a T score ≤−2.5.

3) Patients on glucocorticoids (>5 mg equivalent dose of prednisone) for >3 months.

3. Treatment:

1) Treatment or avoidance of modifiable risk factors for osteoporosis (see Definition, Etiology, Pathogenesis, above).

2) Ensuring optimal serum levels of 25(OH)D3 and adequate calcium intake through diet or calcium supplements.

3) Prevention of falls.

4) Drugs inhibiting bone resorption or stimulating bone formation.

5) Exercise, postfracture rehabilitation.

6) Treatment of pain, improvement of the quality of life.

1. Nutritional management: Optimal pharmacologic treatment requires adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D. Adequate sunlight exposure (~20 min/d) is also recommended.

The best dietary source of calcium (as well as phosphate) is milk and dairy products; low-fat dairy products contain the same amount of calcium as regular products. In persons with lactose intolerance, consumption of lactase-enriched milk or yoghurts should be recommended. About 1000 mg of elemental calcium is delivered with 3 or 4 glasses of milk, 700 mL of yoghurt, 100 to 120 g of hard cheese, or 1000 g of cottage cheese. Various products, such as cereals or fruit juices, are fortified with calcium. The absorption of calcium is inhibited by several foods, including spinach and other vegetables containing oxalate (eg, spinach, rhubarb), large amounts of cereals containing phytic acid (eg, wheat bran), and probably also tea (due to tannins and oxalates). If adequate dietary calcium intake cannot be provided, calcium supplements may be used.

An adequate intake of protein (~1.2 g/kg/d), potassium, and magnesium is necessary to maintain good functioning of the musculoskeletal system and to improve the healing of fractures.Evidence 1Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias and heterogeneity. Shams-White MM, Chung M, Du M, et al. Dietary protein and bone health: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017 Jun;105(6):1528-1543. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.145110. Epub 2017 Apr 12. Review. PMID: 28404575.

2. Exercise:

1) Exercise involving functional and resistance training (≥2 times/wk to reduce falls) appropriate for the individual’s age and functional capacity as well as weight-bearing aerobic exercise are recommended for those with osteoporosis or at risk for osteoporosis.

2) Exercise targeting abdominal and back extensor muscles to enhance core stability and thus to compensate for weakness or postural abnormalities is recommended for individuals who have had vertebral fractures.

3) Exercise that focuses on balance, such as tai chi, or balance and gait training should be considered for those at risk of falls.

4) Hip protectors should be considered for older adults in LTC who are at high risk for fracture.

3. Prevention of falls: Eliminating all risk factors for falls, including correction of vision and improving physical mobility and muscle strength through adequate exercise.Evidence 2Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias. El-Khoury F, Cassou B, Charles MA, Dargent-Molina P. The effect of fall prevention exercise programmes on fall induced injuries in community dwelling older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2013 Oct 29;347:f6234. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6234. Review. PMID: 24169944; PMCID: PMC3812467. Recommend appropriate, nonslippery footwear and avoidance of long-acting hypnotics. Gait aids, such as a walker or cane, may be useful in patients at high risk of falling.

1. Calcium supplements with calcium carbonate (these contain the highest proportion of elemental calcium [40%]) or other formulations such as calcium gluconate, calcium gluconolactobionate, and calcium lactogluconate. Calcium supplements should be taken orally with food at daily doses equivalent to 1 to 1.2 g of elemental calcium, depending on dietary calcium intake. It is debatable whether supplementation of calcium alone (particularly in high doses) or in combination with vitamin D3 may increase the risk of cardiovascular events, although the weight of evidence does not support this concern. Obtaining calcium intake through diet is the preferable route.

2. Vitamin D (cholecalciferol): In adults without vitamin D deficiency, supplementation with cholecalciferol at 800 to 2000 IU/d should be used; in patients with vitamin D deficiency, the doses are much higher. In case of impaired hydroxylation of cholecalciferol, use oral alfacalcidol (in renal failure) or calcitriol, an active form of vitamin D (in severe renal and liver failure).

In patients with obesity, osteoporosis, and inadequate exposure to sunlight or with a malabsorption syndrome, it may be necessary to increase the dose of cholecalciferol even to 4000 IU/d, and in case of severe vitamin D deficiency—25(OH)D3 levels <10 ng/mL—a short course of cholecalciferol at a dose of 7000 to 10,000 IU/d may be required; in such patients serum levels of 25(OH)D3 should be monitored after ~3 months of treatment. Optimal levels are 30 to 50 ng/mL.

Contraindications include hypervitaminosis D, hypercalcemia, and severe liver failure.

Indications for and administration of calcium and vitamin D supplements in patients with CKD: see Chronic Kidney Disease.

3. Bisphosphonates bind to hydroxyapatites in the bone, forming compounds resistant to enzymatic hydrolysis and causing the inhibition of osteoclastic bone resorption. Oral bisphosphonates are the drugs of choice in primary osteoporosis in postmenopausal women, in men, and in patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. In patients with contraindications to oral bisphosphonates and in those with adherence issues, consider IV bisphosphonates.

The optimal duration of bisphosphonate treatment has not been established. After 3 to 5 years, the effectiveness of treatment and adverse effects should be evaluated. Consider discontinuation of bisphosphonates after 3 to 5 years of treatment if the current risk of fractures is not high (ie, the patient has not had an osteoporotic fracture and the T score is >−2.5). However, high-risk patients should not be considered for a drug holiday, as the risk for fracturing outweighs the risk of potential adverse effects. After 2 or 3 years, reassess the risk on the basis of BMD and markers of bone turnover. If during this period the patient has had an osteoporotic fracture or their risk has increased, reintroduce bisphosphonate treatment; however, no data directly proving the benefits and safety of this management strategy are available.

The key adverse effects of oral bisphosphonates are related to the GI tract (eg, esophagitis or esophageal ulcers; adverse effects are less frequent in the case of weekly or monthly administration). In addition, absorption is poor if they are taken with anything but water. Therefore, the tablets should be taken on an empty stomach with plain water and the patient should remain upright for 30 minutes afterwards. Other adverse effects—associated particularly with IV administration—include bone, muscle, and joint pain; flu-like symptoms; rash; decrease in serum calcium and phosphate levels; and atypical femoral fracture. Of note, the risk of atypical femoral fracture has been reported to increase with longer duration of bisphosphate use, so fracture risk should be taken into consideration when evaluating whether to continue therapy after 3 to 6 years of treatment.

Contraindications to oral bisphosphonates include hiatal hernia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, esophageal stenosis or dysmotility, active gastric or duodenal ulcer disease, inability to maintain an upright position for 30 to 60 minutes (relevant to oral preparations only), renal failure (creatinine clearance <35 mL/min), and hypocalcemia.

Agents:

1) Oral alendronate 10 mg once daily or 70 mg once weekly.

2) IV zoledronic acid 5 mg once a year.

3) Oral ibandronate sodium (INN ibandronic acid) 150 mg once a month or IV 3 mg every 3 months.

4) Oral risedronate sodium (INN risedronic acid) 5 mg once daily, 35 mg once a week, or 150 mg monthly.

4. Oral strontium ranelate (available in some countries; not approved for use in North America) at a dose 2 g/d (at bedtime, before sleep, ≥2 h after a meal) may be used in combination with calcium and vitamin D. Strontium ranelate inhibits bone resorption and probably also stimulates bone synthesis (this has not been proven to date). At the beginning of treatment, diarrhea may occur. Strontium ranelate is used in men and women with severe osteoporosis.

The agent is contraindicated in patients with ischemic heart disease, peripheral artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, a history of venous thromboembolism, and in those who are immobilized. Strontium ranelate is not recommended in patients with creatinine clearance <30 mL/min.

5. Denosumab 60 mg subcutaneously every 6 months. This is a human monoclonal antibody against the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), which prevents the activation of the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B (RANK) on the cell surface of osteoclasts and their precursors. Denosumab inhibits the synthesis, function, and survival of osteoclasts, thus decreasing resorption of the compact and trabecular bone. It is recommended for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and in men, and particularly in men with prostate cancer undergoing hormonal treatment who show loss of bone mass (thus being at increased fracture risk) and women with breast cancer where it may be beneficial in disease-free survival. Denosumab may be used in patients with renal failure as it is not excreted through the kidneys; however, these patients are at high risk for developing severe symptomatic hypocalcemia and should be monitored carefully. The effect on BMD may exceed the effect of bisphosphonates.Evidence 3Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. Benjamin B, Benjamin MA, Swe M, Sugathan S. Review on the comparison of effectiveness between denosumab and bisphosphonates in post-menopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2016 Jun;2(2):77-81. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2016.03.003. Epub 2016 Apr 27. Review. PMID: 30775470; PMCID: PMC6372735. After withdrawal of this drug, there may be a rapid loss of bone mass, so alternative treatment (eg, bisphosphonates) should be continued.

6. Teriparatide 20 microg subcutaneously once daily should be considered in those at high fracture risk. This is a recombinant 1-34 N-terminal fragment of the parathyroid hormone molecule. It is indicated in patients with severe osteoporosis and multiple fractures in whom bisphosphonates, strontium ranelate, and denosumab either cannot be used or are ineffective. It should not be used for >24 months (after this time use a bisphosphonate).

Contraindications include hypercalcemia, severe renal failure, other metabolic bone diseases, unexplained elevation in serum alkaline phosphatase levels, history of skeletal irradiation, malignant tumor of the musculoskeletal system, or bone metastases (an absolute contraindication).

7. Abaloparatide is a PTHrP for the treatment of postmenopausal women with severe osteoporosis at high risk for fracture defined as a history of osteoporotic fractures, multiple risk factors for fracture, or those in whom other therapies are not tolerated or ineffective. The dose is 80 microg subcutaneously daily. Use for >2 years during a patient’s lifetime is not recommended.

Warnings and precautions include orthostatic hypotension, hypercalcemia, kidney stones, and hypercalciuria. In addition there is a warning about a dose-dependent risk of osteosarcoma from rat studies (similar to teriparatide), and as a result abaloparatide should not be used in those at increased risk of osteosarcoma, including patients with Paget disease, unexplained elevations in alkaline phosphatase, prior radiation, or malignancy.

8. Romosozumab is a novel anabolic agent for the treatment of osteoporosis. It is a monoclonal antibody that binds sclerostin. Sclerostin is produced by osteocytes and has a negative impact on osteoblastic activity and survival. Romosozumab decreases circulating sclerostin levels, and thus has an anabolic effect on bone formation. It has been shown to significantly reduce vertebral fractures at 12 months and 24 months of treatment (when crossed over to denosumab therapy at 12 months) compared with denosumab therapy; however, there has been no statistically significant reduction in nonvertebral fracture rates. Caution should be taken in patients who have experienced myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke in the previous year, as romosozumab may increase the risk of MI, stroke, and cardiovascular death. However, this elevated risk of cardiovascular events was not shown in the original FRAME (Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis), which examined romosozumab use versus placebo. Additionally, patients with severe kidney disease are at risk of hypocalcemia and should be monitored closely if this drug is initiated.

9. Other drugs reducing fracture risk:

1) Oral raloxifene 60 mg/d reduces the risk of vertebral fractures but at the same time increases the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and incidence of hot flushes. It is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) and as such it also reduces the risk of breast cancer. It may be considered as treatment for osteoporosis in women with risk factors for breast cancer.

2) Estrogen-progesterone (female sex hormones) replacement therapy reduces the risk of vertebral and other fractures in postmenopausal women but at the same time increases the risk of breast cancer, uterine cancer, and DVT. It may be considered for the treatment or prevention of osteoporosis.

3) Salmon calcitonin is not recommended for the treatment of osteoporosis due to an increased risk of malignancy associated with its long-term use. The use of short-term regimens (max 2-4 weeks, 100 IU/d subcutaneously or IM) as analgesic therapy is acceptable in patients with fractures.

FiguresTop

Figure 18.15-1. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) showing the proximal femur, lumbar spine, and bones of the forearm. Illustration courtesy of Dr Shannon Zhang.