Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, HIV Medicine Association

of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/Adult_OI.pdf. Updated August 18, 2021.

Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv/whats-new-guidelines?view=full. Updated August 16, 2021.

National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, and TB Prevention (U.S.). Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Association of Public Health Laboratories. 2018 Quick reference guide: Recommended laboratory HIV testing algorithm for serum or plasma specimens. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/50872. Updated January 2018.

Branson BM, Owen SM, Wesolowski LG, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.), Association of Public Health Laboratories, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, and TB Prevention (U.S.). Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention. Laboratory testing for the diagnosis of HIV infection: updated recommendations. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/23447. Published June 27, 2014.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised surveillance case definition for HIV infection--United States, 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014 Apr 11;63(RR-03):1-10. PubMed PMID: 24717910.

Pepin J. The Origins of AIDS. Cambridge: Oxford University Press; 2011: 18-42.

Etiology and PathogenesisTop

1. Etiologic agent: Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus that infects CD4-positive cells (T helper cells, macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells).

2. Pathogenesis: HIV infects mainly macrophages and activated T cells. The hallmark of primary HIV infection is high viral load, transient reduction in peripheral blood CD4+ T-cell count, and, in most cases, symptoms of acute retroviral disease. Chronic infection is characterized by persistent immune activation and a gradual decline in CD4+ T-cell count. The infection may be clinically asymptomatic for years, but HIV replication continues in the peripheral lymphoid organs and gradually destroys their microenvironment. As the infection progresses, immune homeostasis is disturbed, and the function of numerous organs may be affected.

3. Reservoir and transmission: The reservoir of HIV is humans. The source of infection is another HIV-infected individual. The virus is predominantly transmitted through sexual contact. Other routes of transmission include blood and mother-to-child transmission—transmission to infants during pregnancy, birth, and breastfeeding.

4. Epidemiology: HIV is present worldwide, with the majority of the epidemic principally affecting sub-Saharan Africa. A significant proportion of infected individuals remain undiagnosed until clinically apparent immunodeficiency develops.

5. Risk factors: Sexual intercourse (estimated median risk of HIV transmission per exposure ranges from 1.1% for receptive anal to 0.082% for insertive vaginal intercourse; receptive oral sex, 0.02%); IV drug use (0.67% per needle-sharing event); needlestick injury (0.3% risk); transmission to a newborn from the HIV-positive mother (risk of ~30% without prophylaxis; this may be reduced to <1% if prophylactic treatment is provided to mother and child).

6. Incubation and contagious period: Primary HIV infection, 1 to 4 weeks; development of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in individuals not receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART), 1.5 to 15 years (on average 8-10 years) from the time of infection. An HIV-infected individual becomes contagious within a few days of contracting the virus.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

HIV infection progresses through various stages, which are characterized by distinctive clinical features and immunologic parameters and may be classified as one of 5 HIV infection stages (0, 1, 2, 3, or unknown) based on the CD4+ T-cell count or diagnosis of an opportunistic infection (Table 10.1-1 and Table 10.1-2). Irrespective of infection stages, clinical presentations may include the following:

1. Primary HIV infection (clinical stage 0): Infection within prior 6 months with a documented sequence of negative/indeterminate results prior to the confirmed HIV positive test. Clinically, a primary HIV infection may manifest as acute retroviral syndrome (ARS) with clinical features of a mononucleosis-like illness. The symptoms may be minor and resolve spontaneously within 2 weeks; the most common ARS symptoms include fever, generalized lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, rash, and myalgia/arthralgia. HIV infection is commonly associated with the history of other sexually transmitted infections, especially syphilis. The probability of primary HIV infection increases when:

1) The patient has a history of high-risk sexual exposure in the previous few weeks (currently blood products are rarely a source of infection, as they are screened for HIV).

2) An adult patient has a recent episode of “mononucleosis” or ARS.

3) The patient has signs and symptoms or history of other sexually transmitted diseases (syphilis, gonorrhea).

2. Chronic HIV infection may manifest as the following conditions:

1) Asymptomatic HIV infection occurs after the primary infection and results from establishing a relative balance between HIV replication and the antiviral immune response. Patients not receiving ART may remain asymptomatic for 1.5 to 15 years.

2) Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy (PGL) is observed in the asymptomatic stage and includes enlarged lymph nodes (>1 cm in diameter) in ≥2 regions (except for inguinal nodes) persisting >3 months (key diagnostic criterion).

3) Chronic fatigue; headache; splenomegaly (~30%); increased incidence of nonopportunistic skin, respiratory, and gastrointestinal infections.

4) Symptomatic infection with clinical features not fulfilling the criteria for the AIDS-defining condition; these include infections resulting from decreased CD4+ T-cell counts (Table 10.1-2): herpes zoster (shingles) involving >1 dermatome or recurrent bacillary angiomatosis (red papillary skin lesions caused by Bartonella henselae infection with features resembling Kaposi sarcoma); oral hairy leukoplakia (lesions similar to oral candidiasis, located mainly on the lateral aspects of the tongue); oropharyngeal (thrush) candidiasis or vulvovaginal candidiasis (persistent, recurrent, or resistant to treatment); cervical dysplasia and cervical carcinoma in situ (human papillomavirus [HPV] infection); fever lasting >1 month; persistent diarrhea lasting >1 month; clinical manifestations of thrombocytopenia; listeriosis; peripheral neuropathy; pelvic inflammatory disease.

3. Clinical features of AIDS: Conditions and opportunistic infections indicative of the stage 3 disease as listed in the AIDS surveillance case definition (opportunistic infections and neoplasms: Table 10.1-2). The confirmation of diagnosis requires the presence of anti-HIV antibodies. AIDS diagnosis usually requires prompt ART, as the patient may die of opportunistic infections or neoplasms.

DiagnosisTop

The patient must give his/her informed consent prior to HIV testing. The patient has the right to anonymous testing.

Patient counseling while planning the test and awaiting its results:

1) Provide the patient with psychological support.

2) Review the last or previous HIV test result.

3) If the test result is positive, refer the patient to an HIV specialist.

4) If the test result is negative, refer the patient to the preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) services.

5) Determine the time of the last exposure to a potential risk factor of infection.

6) Establish the circle of the patient's contacts who also should undergo examination.

7) Help the patient reduce tension.

8) Discuss preventive methods in the period of waiting for and after obtaining the result (depending on the result). Such discussion should be carried out by the physician who ordered the examination.

HIV testing should be considered part of differential diagnosis in patients with a condition of unknown etiology that has an atypical course, is resistant to treatment, or recurs, and is potentially related to a known clinical presentation. HIV testing is particularly recommended in the case of a confirmed AIDS-indicator disease (Table 10.1-2), fever of unknown origin, syphilis, molluscum contagiosum, genital herpes simplex, anogenital warts, lymphogranuloma venereum, hepatitis A, B, or C, pneumonia not responding to antimicrobial treatment, aseptic meningitis, focal lesions in the central nervous system (abscess, tumor, demyelination), Guillain-Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis, encephalopathy of unknown etiology, progressive dementia in patients <60 years, vaginal dysplasia, recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, HPV infection and other sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy (including partners of the pregnant women), lung cancer, seminoma, head and neck cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, Castleman disease, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia or lymphopenia of unclear etiology, loss of body weight for unknown reasons, esophageal or oral candidiasis, persistent diarrhea of unclear etiology, colitis of unclear etiology, cachexia of unclear etiology, herpes simplex virus retinitis, varicella-zoster virus infection, Toxoplasma gondii infection, retinopathy of unclear etiology, glomerular and tubular nephropathies of unclear etiology, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis without a positive family history, herpes zoster (recurrent, involving large areas of the skin). Pregnancy is also an indication for testing (partners of the pregnant patient should undergo examination as well).

All individuals presenting with diagnosed syphilis, active tuberculosis, or lymphoma should be screened for HIV infection.

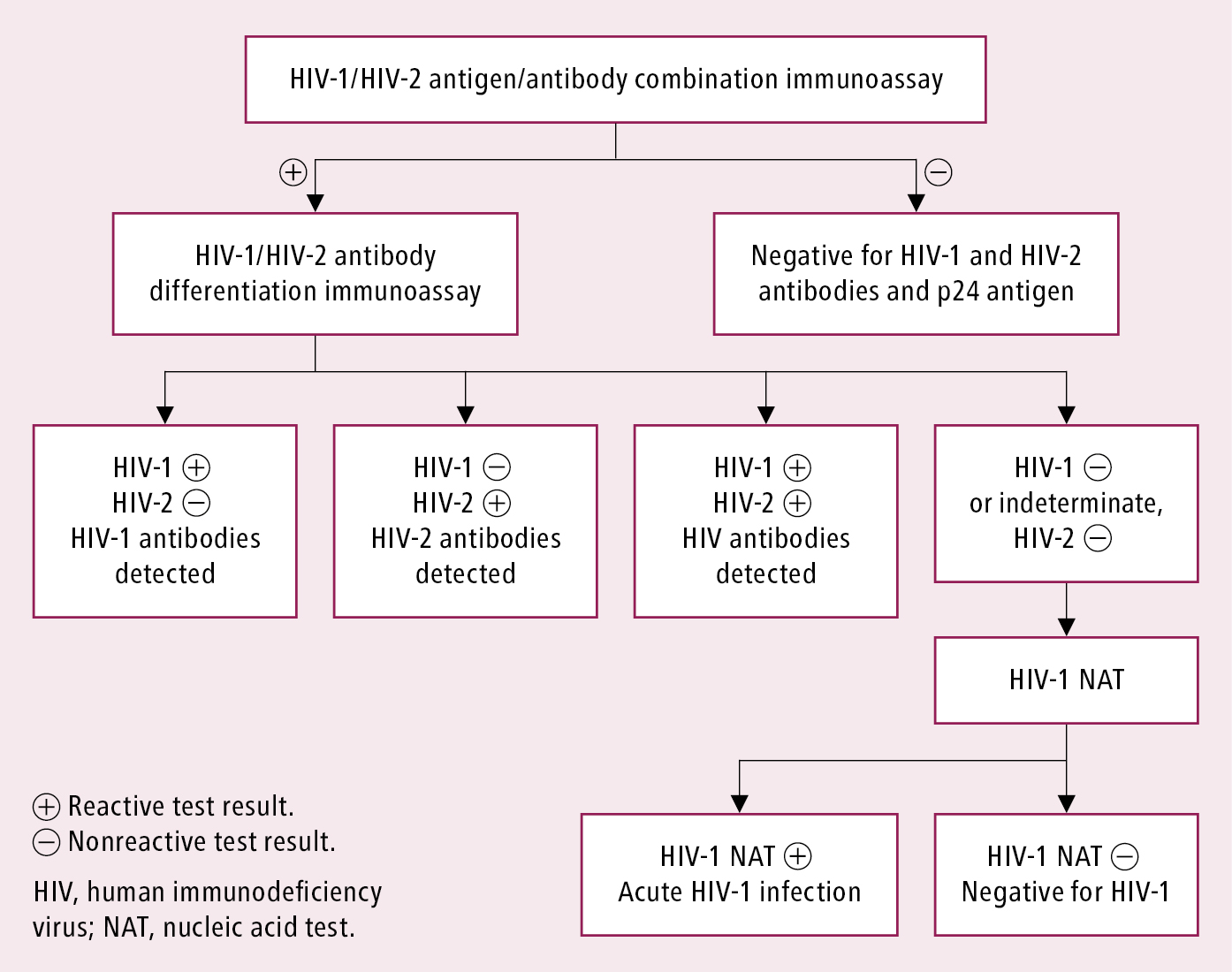

1. Serology (the basis of screening) (Figure 10.1-1): The use of diagnostic tests may depend on their availability in particular jurisdictions. The most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendation indicates fourth-generation testing for antibodies against HIV-1 and HIV-2 and the HIV-1 p24 antigen (antigen/antibody combination immunoassay). If results of all components are negative, the diagnosis of HIV infection is excluded (the test may need to be repeated if exposure occurred <6 weeks before testing). If the result is positive, it is followed by a confirmatory HIV-1/HIV-2 differentiation immunoassay. Detection of antibodies in that test confirms the diagnosis. If no antibodies are detected (either negative or indeterminate results are obtained), a test for detection of viral RNA (HIV-1 nucleic acid testing [NAT]) is performed to exclude acute infection.

A Western blot assay, performed exclusively by reference centers and used to confirm the initial positive antibody test result, had limited ability to detect early primary HIV infection and is not used if HIV-1/HIV-2 differentiation immunoassay is available.

In relevant cases in which negative test results were obtained, testing should be repeated after the serologic window period, that is, 6 weeks from a situation that could be associated with the risk of infection. The window period for a fourth-generation test (p24 antigen and anti-HIV antibodies) is between 2 and 6.5 weeks. The test can detect HIV in 50% of people by 18 days after exposure, and in 99% of people by 44 days after exposure. In addition, serologic testing for anti-HIV antibodies and the p24 antigen should be offered to the sexual partner of a patient who is suspected of having HIV infection, particularly if the patient has acute retroviral syndrome, as this is when the risk of transmission is the highest.

2. Decreased CD4+ T-cell counts; a CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratio <1 (Table 10.1-1). The CD4+ T-cell percentage usually corresponds to CD4+ count: for CD4+ count ≥0.5×109/L, the percentage is usually >25%, and for CD4+ count <0.2×109/L, <14%.

3. Virology (detection of HIV RNA in serum using molecular biology methods (quantitative testing), including DNA and RNA detection, viral culture, or HIV sequence): Diagnostics of seronegative/indeterminate individuals suspected of primary HIV infection, newborns of HIV-positive mothers. Quantitative assays (number of HIV RNA copies/mL) are used to determine viral load and to monitor the effectiveness of ART.

Confirmed HIV infection (Figure 10.1-1) and fulfillment of the clinical and immunologic criteria that determine the stage of the disease (Table 10.1-1 and Table 10.1-2). Pretest and posttest counseling is necessary. In patients with primary HIV infection, the screening and confirmatory serologic tests detecting anti-HIV antibodies may be negative or inconclusive. Therefore, the diagnosis may be established solely on the basis of serum HIV RNA detection, or serum p24 antigen if the assays detecting the virus are not available (negative p24 antigen test results do not exclude acute infection).

It is highly recommended to test sexual partners of the individuals who test positive for HIV, are diagnosed with primary HIV infection, or both.

TreatmentTop

1. Combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) is a combination of 2 or 3 drugs acting synergistically to inhibit HIV replication, which allows for at least partial functional restoration of the immune system (increase in CD4+ T-cell counts, sometimes even up to normal values) and elimination of active HIV replication (serum/plasma HIV RNA levels below the limit of detection using the molecular assay), but it does not eradicate the virus nor achieve a total virologic clearance. cART significantly reduces the risk of HIV transmission and improves survival and quality of life. It is used as a long-term treatment option to suppress HIV replication for as long as possible.

2. Indications for cART: The judgement on when to start cART has changed in the light of the START (Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Therapy) trial. Evidence is accumulating that starting ART on the same day of HIV diagnosis is feasible and acceptable to HIV-positive persons. cART is recommended in all adults with chronic HIV infection irrespective of CD4+ cell counts.Evidence 1Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). INSIGHT START Study Group, Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, et al. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 27;373(9):795-807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. Epub 2015 Jul 20. PubMed PMID: 26192873; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4569751. TEMPRANO ANRS 12136 Study Group, Danel C, Moh R, Gabillard D, et al. A Trial of Early Antiretrovirals and Isoniazid Preventive Therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 27;373(9):808-22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507198. Epub 2015 Jul 20. PubMed PMID: 26193126. HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration, Ray M, Logan R, Sterne JA, et al. The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2010 Jan 2;24(1):123-37. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283324283. PubMed PMID: 19770621; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2920287. An exception to this rule is cryptococcal meningitis, where a delay of ≥2 weeks and possibly up to 10 weeks is suggested, especially in individuals with a low white cell count in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or with elevated intracranial pressure (ICP). Another exception is tuberculosis, where starting cART is suggested in pregnant women as early as feasible and in individuals with CD4+ cell count <0.05×109/L within 2 weeks, but in those with CD4+ counts ≥0.05×109/L it could be delayed for up to 8 weeks. Patients with tuberculous meningitis are at higher risk of adverse event and deaths with early initiation of treatment.

3. Classes of drugs used in cART: Integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) are the first-line treatment options, combined with 2 nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs):

1) Nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs): Abacavir, emtricitabine, lamivudine, tenofovir and its derivatives—alafenamide (TAF) and disoproxil (TDF), zidovudine.

2) Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs): Efavirenz, etravirine, nevirapine, rilpivirine, doravirine in combination with lamivudine and disoproxil.

3) Protease inhibitors (PIs): Darunavir, fosamprenavir, indinavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, saquinavir, tipranavir, atazanavir.

4) Integrase inhibitors (integrase strand transfer inhibitors [INSTIs]): Raltegravir, elvitegravir/cobicistat, dolutegravir, bictegravir, cabotegravir.

5) Entry inhibitors: Enfuvirtide, fostemsavir, ibalizumab.

6) CCR5 inhibitors: Maraviroc.

Recommended combinations of drugs in ART-naive patients: 1 NRTI + INSTI; 2 NRTIs + NNRTI; 2 NRTIs + PI (+ low-dose ritonavir or cobicistat); 2 NRTIs + INSTI (most current preferred regimens are INSTI-based). Single-tablet drug combinations are recommended.

PrognosisTop

The implementation of cART in HIV-infected individuals results in the restoration of immune function (lymphocyte CD4+ counts, proportions, and function), suppression of HIV replication, decrease in the risk of AIDS-related and non–AIDS-related conditions, as well as improvement in survival rates (life expectancy of an HIV-positive patient receiving cART in whom stable lymphocyte CD4+ counts >0.5×109/L have been restored is similar to individuals who are HIV-negative).Evidence 2 Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness (high-risk and older patients possibly underrepresented). Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, et al; North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) of IeDEA. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One. 2013 Dec 18;8(12):e81355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081355. eCollection 2013. PubMed PMID: 24367482; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3867319.

PreventionTop

1. Vaccination: No vaccine against HIV is available.

2. Postexposure prophylaxis: see Occupational Exposures to Blood-Borne Viral Infections.

3. Preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP): Daily oral PrEP with fixed-dose combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg and emtricitabine 200 mg has been shown to be safe and effective in reducing the risk of acquisition of HIV in adults. PrEP is recommended as a prevention option in (for full details, see www.cmaj.ca):

1) Men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women who are sexually active and at substantial risk of acquiring HIV infection.

2) Adult heterosexually active men and women who are at substantial risk of acquiring HIV infection.

3) Adult persons who inject drugs and are at substantial risk of acquiring HIV infection (eg, sharing injection drug paraphernalia).

PrEP provides a significant decrease in the transmission rate in persons with high risk of sexual transmission, in whom we recommend its use,Evidence 3Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al; iPrEx Study Team. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec 30;363(27):2587-99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. Epub 2010 Nov 23. PubMed PMID: 21091279; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3079639. Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. No New HIV Infections With Increasing Use of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis in a Clinical Practice Setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Nov 15;61(10):1601-3. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ778. Epub 2015 Sep 1. PubMed PMID: 26334052. McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2015 Sep 9. pii:S0140-6736(15)00056-2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 26364263. and in injection drug users, in whom we suggest its use.Evidence 4Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). A weak rather than strong recommendation due to a smaller absolute benefit and indirectness to the North American population. Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness to the North American population. Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al; Bangkok Tenofovir Study Group. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013 Jun 15;381(9883):2083-90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7. Epub 2013 Jun 13. PubMed PMID: 23769234. On-demand PrEP (starting with 2 pills 2-24 h before sexual activity and 1 tablet daily for 2 days thereafter) is another option.

Of note, injection of cabotegravir and rilpivirine every 2 months may become a preferred option.Evidence 4Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. Overton ET, Richmond G, Rizzardini G, et al. Long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine dosed every 2 months in adults with HIV-1 infection (ATLAS-2M), 48-week results: a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3b, non-inferiority study. Lancet. 2021 Dec 19;396(10267):1994-2005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32666-0. PMID: 33308425.

4. Treatment of an infected partner: HIV-infected individuals with HIV RNA copies <200/mL treated with antiretroviral therapy do not transmit the virus through sexual contact with seronegative persons. Therefore the effective antiretroviral treatment of as many people infected as possible is—along with widespread testing to detect as many infections as possible—the most effective means of limiting the HIV pandemic.

5. Prophylaxis of vertical transmission (mother–child): Perform HIV screening at the end of the first trimester and in the third trimester of pregnancy. The aim of these tests is to detect HIV infection as early as possible and to initiate treatment in a pregnant patient, so that the HIV RNA is undetectable at 34 to 36 weeks of pregnancy (full treatment effectiveness). In such a situation, the risk of HIV transmission from a woman to the fetus is close to zero, and perinatal prophylaxis involves only giving the newborn azidothymidine for 28 days. There is no need to perform a planned cesarean delivery. If HIV viral load is detectable at 34 to 36 weeks of pregnancy, the methods of delivery and pharmacologic prophylaxis require specialist consultation. Screening for HIV infection and other sexually transmitted infections should also include partners of pregnant patients.

6. Behavioral recommendations to prevent HIV infection:

1) Use of condoms.

2) Avoiding high-risk sexual contacts.

3) Limiting the number of sexual partners.

4) Testing for HIV (and other viruses spread by sexual contact) every 3 months (and as needed) in individuals at high risk of infection.

5) Use of needle, syringe, and additional equipment exchange programs.

6) Substitution treatment in the case of opioid addiction or referral to addiction therapy centers.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Immunologic criteria (CD4+ T-cell count) |

Clinical category | ||

|

A (asymptomatic ARS or PGL) |

B (symptomatic, not A or C) |

C (AIDS-indicator diseases) | |

|

≥500/microL |

A1 |

B1 |

C1a |

|

200-499/microL |

A2 |

B2 |

C2a |

|

<200/microL |

A3a |

B3a |

C3a |

|

a AIDS is recognized in categories A3, B3, C1, C2, and C3. | |||

|

Adapted from Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Sep 1;49(5):651-81. | |||

|

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ARS, acute retroviral syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PGL, persistent generalized lymphadenopathy. | |||

|

Stage-3 defining opportunistic infections |

– Bacterial infections, multiple or recurrenta – Candidiasis of bronchi, trachea, or lungs – Candidiasis of esophagus – Cervical cancer, invasiveb – Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary – Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary – Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal (>1 month’s duration) – Cytomegalovirus disease (other than liver, spleen, or nodes), onset at age >1 month – Cytomegalovirus retinitis (with loss of vision) – Encephalopathy attributed to HIV – Herpes simplex: chronic ulcers (>1 month’s duration) or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis (onset at age >1 month) – Histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary – Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (>1 month’s duration) – Kaposi sarcoma – Lymphoma, Burkitt (or equivalent term) – Lymphoma, immunoblastic (or equivalent term) – Lymphoma, primary, of brain – Mycobacterium avium complex or Mycobacterium kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary – Mycobacterium tuberculosis of any site, pulmonary,b disseminated, or extrapulmonary – Mycobacterium, other species or unidentified species, disseminated or extrapulmonary – Pneumocystis jiroveci (previously known as Pneumocystis carinii) pneumonia – Community-acquired pneumonia, recurrentb – Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy – Salmonella septicemia, recurrent – Toxoplasmosis of brain, onset at age >1 month – Wasting syndrome attributed to HIV |

|

Neoplastic diseases |

– Kaposi sarcoma – Lymphoma (Burkitt, primary lymphoma of brain, immunoblastic) – Invasive cervical carcinoma |

|

Clinical syndromes |

– HIV-related encephalopathy – HIV-related wasting |

|

a Only among children aged <6 years. b Only among adults, adolescents, and children aged ≥6 years. | |

|

Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised surveillance case definition for HIV infection--United States, 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014 Apr 11;63(RR-03):1-10. | |

|

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus. | |

Figure 10.1-1. Recommended laboratory HIV testing algorithm for serum or plasma specimens. Based on: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Laboratory Testing for the Diagnosis of HIV Infection: Updated Recommendations; Laboratory testing for the diagnosis of HIV infection: updated recommendations; and 2018 Quick reference guide: Recommended laboratory HIV testing algorithm for serum or plasma specimens.