Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al; ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021 Oct 22;60(4):727-800. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezab389. PMID: 34453161.

Baumgartner H, De Backer J, Babu-Narayan SV, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021 Feb 11;42(6):563-645. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa554. PMID: 32860028.

Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e35-e71. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000932. Epub 2020 Dec 17. Erratum in: Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e228. Erratum in: Circulation. 2021 Mar 9;143(10):e784. PMID: 33332149.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Aortic stenosis (AS) results from thickened or calcified valve leaflets leading to restricted leaflet motion, reduced aortic valve area (AVA), and transvalvular flow obstruction. AS is most frequently an acquired disease (age-related degenerative valve disease, with rheumatic disease rarely seen) but may also be congenital (most frequently a bicuspid aortic valve).

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

1. Symptoms: AS remains asymptomatic for a long time. It may cause angina, palpitations, dizziness, presyncope or syncope, dyspnea, and in more advanced disease, resting dyspnea. Classification of severity: Table 3.18-3.

2. Signs: Cardiac impulse is diffuse, sustained, and displaced laterally and inferiorly. A systolic thrill may be palpable at the base of the heart and transmitted to the carotid arteries (in patients with severe stenosis). An ejection systolic murmur is present, although its intensity may not reflect the severity of stenosis; the murmur radiates to the carotid arteries and the later the murmur peaks, the more severe the stenosis. An aortic ejection click is audible in patients with elastic leaflets (commonly bicuspid valves). The aortic component of the second heart sound is soft, reverse split, or absent (in severe stenosis); sometimes a fourth heart sound is audible. The pulse is low-amplitude and slow-rising—“parvus and tardus” (in elderly patients these pulse features may be absent due to systemic arteriosclerosis). Patients may have a brachial-radial delay.

3. Natural history: The rate of progression of AS is highly variable. In asymptomatic patients the risk of sudden cardiac death is low but rapidly increases with the onset of the 3 cardinal symptoms: syncope, angina, and heart failure. The average survival of untreated patients with such symptoms is 2 to 3 years.

DiagnosisTop

Diagnosis is based on typical clinical features and echocardiography results.

1. Electrocardiography (ECG) is usually normal in mild to moderate AS. In severe AS, features of left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy with strain pattern are commonly present.

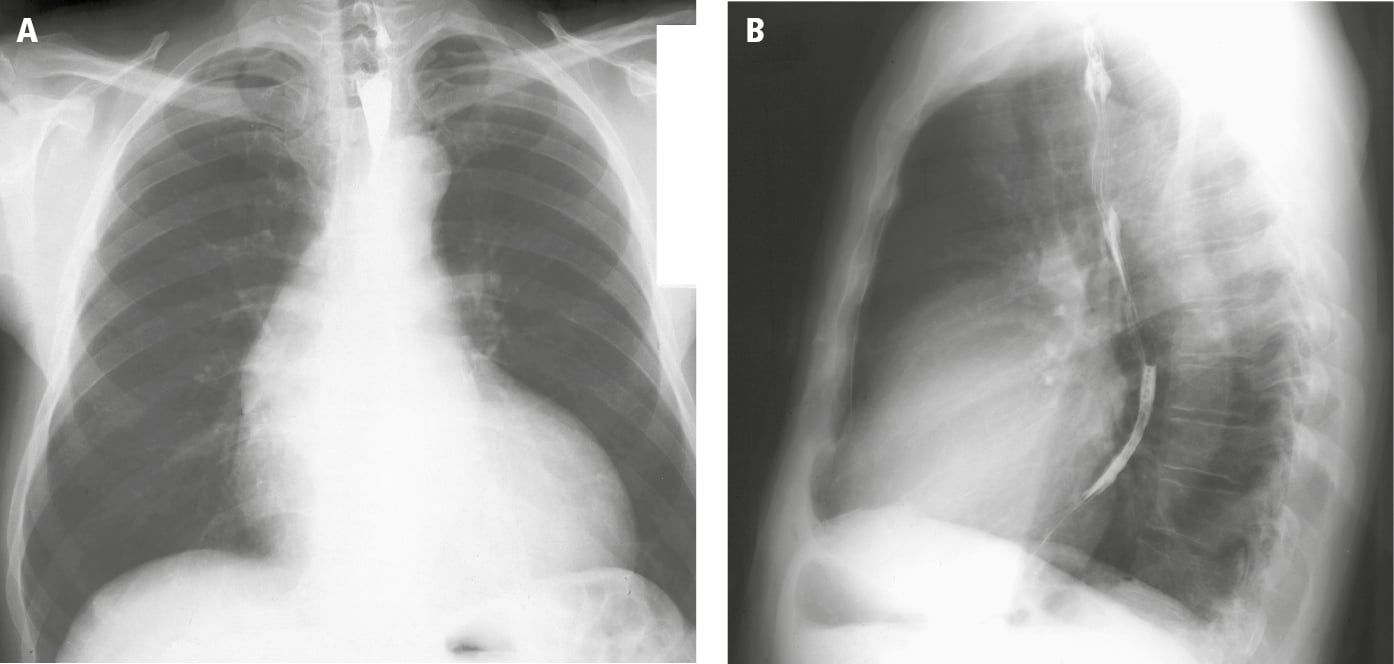

2. Chest radiography (Figure 3.18-1) remains normal for many years. In severe AS, LV hypertrophy and poststenotic dilation of the ascending aorta are observed. Calcifications of the aortic valve may be seen.

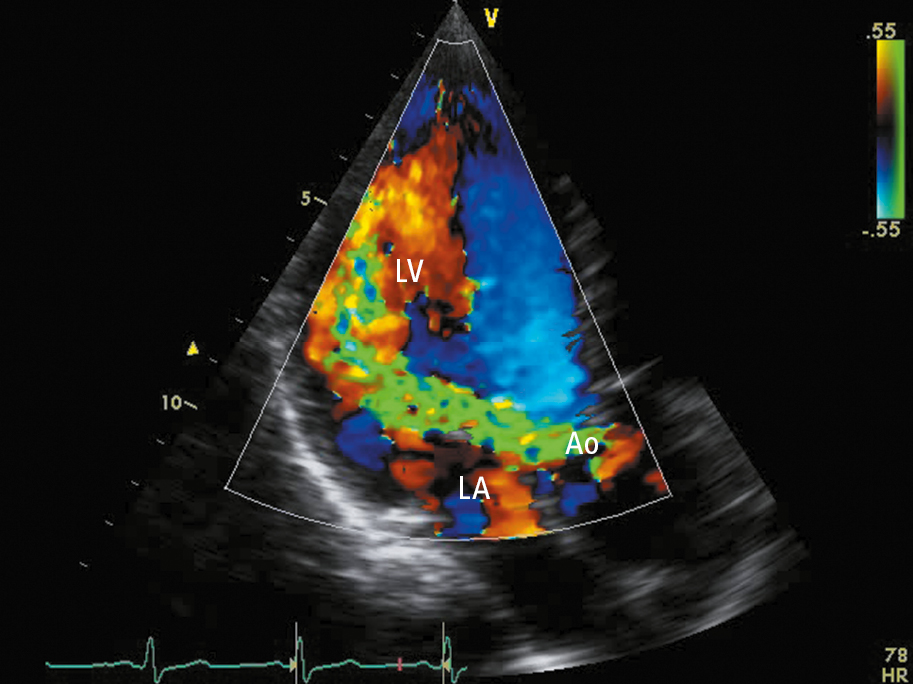

3. Doppler echocardiography (Figure 3.18-2) is used to confirm the diagnosis of AS, assess its severity, evaluate LV structure and function, assess valve morphology, aortic root, and ascending aorta, and monitor the course of the disease. A thickened, calcified aortic valve with reduced leaflet excursion is seen. Doppler echocardiography allows for determination of the severity of stenosis by measuring the aortic jet velocity, peak and mean transvalvular pressure gradients, and AVA (Table 3.18-3). In patients with low-flow low-gradient AS (AVA <1 cm2, but a mean aortic valve gradient <40 mm Hg and/or peak aortic valve velocity <4.0 cm/s), the most common cause is depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (ejection fraction <40%) resulting in low transvalvular flow; in such cases cardiac computed tomography (CT) (see below) and dobutamine stress echocardiography can be performed to distinguish true severe AS from “pseudosevere AS” and to help predict perioperative mortality (expert input usually required).Evidence 1Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know the true prognostic value of the test). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision (low number of observed events). Monin JL, Quéré JP, Monchi M, et al. Low-gradient aortic stenosis: operative risk stratification and predictors for long-term outcome: a multicenter study using dobutamine stress hemodynamics. Circulation. 2003 Jul 22;108(3):319-24. Epub 2003 Jun 30. PubMed PMID: 12835219. Levy F, Laurent M, Monin JL, et al. Aortic valve replacement for low-flow/low-gradient aortic stenosis operative risk stratification and long-term outcome: a European multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Apr 15;51(15):1466-72. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.067. PubMed PMID: 18402902.

4. Noncontrast gated cardiac CT: Aortic valve calcium scoring can provide a morphologic estimation of the severity of AS and risk of adverse outcomes with medical therapy. Severe AS is unlikely with calcium scores <800 in women and <1600 in men but likely with calcium scores >1200 in women and >2000 in men. CT is the preferred modality to assess valve anatomy, annulus dimensions, root dimensions, and feasibility of vascular access when intervention is being considered.

5. Cardiac catheterization may be considered in cases of inconsistent clinical and echocardiographic findings, and to exclude significant coronary artery stenosis before aortic valve surgery. Coronary angiography is recommended before surgical treatment of AS in patients with severe valvular heart disease and one of the following:

1) A history of coronary artery disease (CAD).

2) Suspected myocardial ischemia (chest pain, abnormal results of noninvasive investigations).

3) LV systolic dysfunction.

4) Men >40 years of age, postmenopausal women.

5) ≥1 cardiovascular risk factor (in patients at low risk of atherosclerosis, the diagnosis of CAD may be excluded using coronary CT angiography).

Differential diagnosis should include supravalvular AS and membranous subvalvular stenosis, both of which can be readily identified by echocardiography. Dynamic LV outflow tract obstruction can cause flow acceleration and high transvalvular gradients; however, the carotid upstroke is rapid (not delayed as in AS), while on echocardiography, the aortic valve is not restricted in motion and the shape of the Doppler spectral tracing is “dagger-shaped,” not parabolic as in AS.

TreatmentTop

1. Mild or moderate AS: Medical treatment and follow-up visits (every 1-2 years in mild AS and every year in moderate AS) with echocardiography (every 3-5 years in mild AS and every 1-2 years in moderate AS).

2. Severe AS: In general, an opinion regarding valve replacement from a multidisciplinary team should be obtained. Further details: see below.

1. Aortic valve replacement (AVR) is the key method of treatment in the case of severe AS. AVR is recommended in:

1) Patients with severe AS and symptoms related to AS (syncope, angina, or heart failure). In such cases, urgent intervention is indicated.

2) Asymptomatic patients with severe AS in any of the following cases:

a) LVEF <50% due to AS.

b) Abnormal exercise test results showing symptoms on exercise clearly related to AS (valve replacement may be considered if exercise leads to a drop in blood pressure below baseline).

c) Other indications for cardiac surgery including severe coronary disease, aortopathy, and nonaortic valve disease.

d) Other high risk features including very severe aortic stenosis (velocity >5 m/s), rapid progression (velocity increases >0.3 m/s per year), elevated B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels.

2. Modality of AVR: Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) are options for treatment of aortic stenosis. Choice among treatment modalities is best made by an interdisciplinary valve team. Specific treatment options include:

1) TAVR with balloon-expandable or self-expanding valve: TAVR involves implantation of a bioprosthetic valve via transarterial access (usually transfemoral). Balloon-expandable and self-expanding technologies are used.

2) SAVR with a bioprosthetic valve: SAVR with a bioprosthetic valve is preferred in older patients (usually >65 years of age) as durability is superior compared with younger patients and the need for long-term anticoagulation is avoided.

3) SAVR with a mechanical valve: SAVR with a mechanical valve is used in younger patients because of their durability. Lifelong anticoagulation with warfarin is required in these patients.

4) SAVR with pulmonary homograft (Ross procedure): SAVR with transplant of the pulmonary valve to the aortic position is a desirable but more technically complex approach in younger patients.

Among patients eligible for both SAVR and TAVR, TAVR is associated with reduced rates of mortality and stroke, kidney injury, new-onset atrial fibrillation, and major bleeding but with increased rates of vascular complications, need for permanent pacemaker implantation (depending on valve type), and paravalvular leak.Evidence 2Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the relatively small number of events Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al; Evolut Low Risk Trial Investigators. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Self-Expanding Valve in Low-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 2;380(18):1706-1715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816885. Epub 2019 Mar 16. PubMed PMID: 30883053.Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al; PARTNER 3 Investigators. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Balloon-Expandable Valve in Low-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 2;380(18):1695-1705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814052. Epub 2019 Mar 16. PubMed PMID: 30883058. Patients with other indications for cardiac surgery should undergo SAVR. TAVR should be considered in those ineligible for surgery.Evidence 3Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the large number of patients who crossed over and a relatively small number of events.Kapadia SR, Leon MB, Makkar RR, et al; PARTNER trial investigators. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement compared with standard treatment for patients with inoperable aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 Jun 20;385(9986):2485-91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60290-2. Epub 2015 Mar 15. PubMed PMID: 25788231. TAVR is an acceptable (and may be the preferred) option in patients at both lowEvidence 4Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the relatively small number of eventsSiontis GC, Praz F, Pilgrim T, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation vs. surgical aortic valve replacement for treatment of severe aortic stenosis: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2016 Dec 14;37(47):3503-3512. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw225. Epub 2016 Jul 7. PubMed PMID: 27389906. and high surgical riskEvidence 5Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the degree of imprecision. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, et al; PARTNER 1 trial investigators. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 Jun 20;385(9986):2477-84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60308-7. Epub 2015 Mar 15. PubMed PMID: 25788234. (Table 3.18-4).

Patients with implanted prosthetic mechanical valves require lifelong oral anticoagulant therapy (with international normalized ratio [INR] dependent on thrombogenicity of the artificial valve: Table 3.18-5). In patients considered to have acceptable risk of bleeding, especially those with coexisting CAD, low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) could be added.Evidence 6Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias and imprecision. Whitlock RP, Sun JC, Fremes SE, Rubens FD, Teoh KH; American College of Chest Physicians. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for valvular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(2 Suppl):e576S-600S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2305. PubMed PMID: 22315272; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3278057. In the case of relative contraindications to oral anticoagulants (eg, athletes or women planning to become pregnant), consider other modalities of surgical treatment: valvuloplasty, implantation of a heterograft (bioprosthetic valve) or a homograft, the Ross procedure (using the patient’s own pulmonary valve to replace the diseased aortic valve, with implantation of a homograft to replace the pulmonary valve).

Patients with implanted bioprosthetic or TAVR valves are typically prescribed lifelong low-dose ASA for thromboprophylaxis. This is omitted in patients requiring an anticoagulant for another indication (eg, atrial fibrillation). Dual antiplatelet therapy is continued after TAVR in patients already receiving therapy for coronary stents.Evidence 7Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to inclusion of nonrandomized data, and a small number of events. Vavuranakis M, Siasos G, Zografos T, et al. Dual or Single Antiplatelet Therapy After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(29):4596-4603. Review. PubMed PMID: 27262328. Anticoagulation is commonly prescribed for the first 3 to 6 months following bioprosthetic SAVR.

1. To reduce or control symptoms:

1) Hypertension: Control hypertension with beta-blockers or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) (care should be taken to avoid overmedication and resultant hypotension). With ACEIs, start with a low dose and slowly titrate. In patients who have symptomatic AS, try to avoid preload- and afterload-reducing agents that may produce hypotension.

2) Pulmonary congestion: Diuretics and ACEIs (use with caution, as a too rapid preload reduction decreases cardiac output and blood pressure), beta-blockers (in patients with LV hypertrophy and LV systolic dysfunction, or with atrial fibrillation).

3) Atrial fibrillation: Electrical cardioversion (not to be performed prior to surgical treatment of AS in patients with severe AS who are hemodynamically stable). In the case of persistent atrial fibrillation, administer beta-blockers (the preferred agents) or calcium channel blockers (diltiazem or verapamil) to control the ventricular rate, although such calcium channel blockers are contraindicated in patients with depressed LVEF (<50%). Digoxin can be added to beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers to augment ventricular rate control. Amiodarone can be used in selected cases alone or with beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers, but it should be avoided if the patient is receiving digoxin.

4) Angina: Beta-blockers, nitrates (use with caution).

2. Prevention of infective endocarditis: see Infective Endocarditis.

ComplicationsTop

Sudden cardiac death, peripheral embolism, infective endocarditis (more frequent in younger patients with minor valvular lesions), coagulopathy (acquired von Willebrand syndrome), aortic dissection (most often in patients with a bicuspid aortic valve and aortopathy), right ventricular failure (rare).

PrognosisTop

The prognosis is favorable in asymptomatic patients. The onset of symptoms is associated with a worse prognosis, as the average survival time is 2 years from the onset of heart failure, 3 years from the onset of syncope, and 5 years from the onset of angina. Surgical treatment improves prognosis.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Aortic stenosis | |||

|

Mild |

Moderate |

Severe | |

|

AVA (cm2) |

>1.5 |

1.0-1.5 |

<1.0 (0.6 cm2/m2 BSA) |

|

Mean gradient (mm Hg) |

<25 |

25-39 |

≥40 |

|

Jet velocity (m/s) |

<3 |

3-3.9 |

≥4 |

|

Doppler velocity index or dimensionless index |

>0.50 |

0.25-0.50 |

<0.25 |

|

Based on Circulation. 2014;129(23):e521-643. | |||

|

AVA, aortic valve area; BSA, body surface area. | |||

|

Factors favoring TAVR |

Factors favoring SAVR |

|

– Isolated symptomatic severe aortic stenosis with acceptable aortic and vascular anatomy for transcatheter replacement – Noncardiac comorbidities that increase operative risks and reduce ability to recover from sternotomy |

– Young patients benefiting from durability of mechanical valves – Multilevel obstruction (eg, involving left ventricular outflow tract) – Surgical intervention required for coronary disease, aortopathy, nonaortic valve disease, or endocarditis – Presence of left ventricular thrombus – Inadequate vascular access (vessel size, calcification, tortuosity) or factors that increase technical difficulty of TAVR |

|

SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement. | |

|

Risk of thrombosis associated with the prosthesis |

Examples of mechanical valves |

Target INR depending on the number of risk factorsa | |

|

No risk factors |

≥1 risk factor | ||

|

Low |

– Carbomedics (aortic) – Medtronic Hall – ATS – Medtronic Open Pivot – St. Jude Medical – Sorin Bicarbon |

2.5 |

3.0 |

|

Medium |

Other bileaflet valves |

3.0 |

3.5 |

|

High |

– Lillehei-Kaster – Omniscience – Starr-Edwards – Björk-Shiley – Other tilting disc valves |

3.5 |

4.0 |

|

a Risk factors: replacement of the mitral or tricuspid valve; prior thromboembolic event, atrial fibrillation, mitral stenosis of any severity, left ventricular ejection fraction <35%. | |||

|

Adapted from Eur Heart J. 2022 Feb 12;43(7):561-632. | |||

|

INR, international normalized ratio. | |||

Figure 3.18-1. Posteroanterior (PA; A) and lateral (B) chest radiography: left ventricular hypertrophy and poststenotic dilatation of the ascending aorta (sometimes called the aortic configuration). Figure courtesy of Dr Jerzy Walecki.

Figure 3.18-1. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) (apical long-axis view): severe aortic regurgitation (regurgitation jet marked in green). Ao, aorta; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle.