American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR). American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022.

Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2020 Sep 1;177(9):868-872. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.177901. PMID: 32867516. Accessed January 18, 2021.

Taylor D, Barnes TRE, Young AH. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. 13th ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2018.

Remington G, Addington D, Honer W, Ismail Z, Raedler T, Teehan M. Guidelines for the Pharmacotherapy of Schizophrenia in Adults. Can J Psychiatry. 2017 Sep;62(9):604-616. doi: 10.1177/0706743717720448. Epub 2017 Jul 13. PMID: 28703015; PMCID: PMC5593252.

Pringsheim T, Kelly M, Urness D, Teehan M, Ismail Z, Gardner D. Physical Health and Drug Safety in Individuals with Schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2017 Sep;62(9):673-683. doi: 10.1177/0706743717719898. Epub 2017 Jul 18. PMID: 28718324; PMCID: PMC5593246.

Galletly C, Castle D, Dark F, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016 May;50(5):410-72. doi: 10.1177/0004867416641195. PMID: 27106681.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

DefinitionTop

Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders are classified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) as abnormalities in ≥1 of the following 5 domains, defined as criterion A symptoms, where ≥1 of these symptoms must be point 1, 2, or 3:

1) Delusions.

2) Hallucinations.

3) Disorganized speech (eg, derailment, incoherence).

4) Grossly disorganized or abnormal motor behavior (including catatonia).

5) Negative symptoms (eg, flat affect, avolition).

These conditions, distinguished by the presence and timing of specific symptoms, include (but are not limited to) schizophrenia, brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder, and psychotic disorder due to another medical condition.

The focus of this chapter is on the clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of schizophrenia as the most common psychotic disorder. The chapter will also highlight the epidemiology and etiology of substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder as well as psychotic disorder due to another medical condition, as these are important differential diagnoses to be aware of.

“Psychosis” is a symptom, not a disease. Importantly, psychosis is an umbrella term and can present in a number of other conditions, including major depressive disorder with psychotic features, bipolar disorder with psychotic features, dementia, and delirium. These conditions are detailed elsewhere in this textbook.

EpidemiologyTop

Nearly 3 in 100 people will experience some form of psychotic symptoms within their lifetime. The lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia is 0.3% to 0.7%. Although schizophrenia can occur at any age, the average age of onset is in adolescence and early adulthood. Men tend to be diagnosed earlier (age 18-25 years) than women (age 25-35 years). The lifetime prevalence for schizoaffective disorder is 0.3%, whereas for delusional disorder it is 0.03% to 0.18%. The prevalence of psychotic symptoms in patients with dementia due to Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, dementia due to Parkinson disease, and dementia with Lewy bodies is ~30%, 40%, 50%, and 75%, respectively. The prevalence of substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder is unknown, although it is not a rare occurrence, as between 7% and 25% of first psychotic episodes are classified in some geographical areas as a substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder. Further, a significant number of individuals using illicit substances experience psychotic symptoms during their lifetime. Substance-induced psychosis is also a predictor for the development of schizophrenia, as ~50% of patients diagnosed with cannabis-induced psychosis will convert to a diagnosis of schizophrenia within 8 years. Whether cannabis use is a causal factor in these cases or simply unmasks schizophrenia at an earlier time is less clear. The lifetime prevalence of psychotic disorder due to another medical disorder ranges from 0.21% to 0.54%, with increasing likelihood in the older adult population.

Risk Factors and EtiologyTop

While no single cause has been identified, a number of risk factors have been associated with the development of schizophrenia. Genetic, environmental, and sociodemographic factors include winter/spring season of birth, urbanicity, and being an ethnic minority in a low ethnic density area. Immigration has often been noted as a risk factor, with both first- and second-generation immigrants being at greater risk of developing schizophrenia. Other purported risk factors include obstetric complications and advanced paternal age at conception.

Psychosis can be secondary to other causes such as systemic medical and neurologic illness or medication and substance misuse. While not pathognomonic, some features that can differentiate secondary from primary psychiatric causes include temporal association with substance use or physical illness, older age at onset, absent family psychiatric history, and visual and olfactory hallucinations.

Psychotic Disorder due to Another Medical Condition

Illness affecting many of the body’s systems can precipitate symptoms of psychosis. As noted in the DSM-5-TR criteria for psychotic disorder due to another medical condition, the symptoms of psychosis cannot be explained by another psychiatric disorder and there must be evidence in history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that suggests a pathophysiologic association between the symptoms of psychosis and a specific medical condition. While delirium and dementia (major neurocognitive disorders) can often present with psychotic symptoms, they are excluded from the diagnosis of psychotic disorder due to another medical condition, each having their own separate diagnosis in the DSM-5-TR. Medical conditions that can precipitate a psychotic episode: Table 16.18-1.

Substance/Medication-Induced Psychotic Disorder

As noted in the DSM-5-TR, a number of substances/medications are capable of causing psychotic symptoms, either in the intoxication or withdrawal phase. Common precipitants include drugs such as cannabis or methamphetamine as well as prescribed medications such as glucocorticoids or dopamine agonists. Substances/medications that can precipitate psychosis: Table 16.18-2.

Clinical FeaturesTop

1. Delusions are defined as false, fixed beliefs that are not amenable to change when presented with clear contradictory reasoning or evidence. They are not consistent with the patient’s religious or cultural background. Delusions can be classified into various types, such as persecutory, referential, somatic, religious, grandiose, erotomanic, and nihilistic. The most common type of delusions is persecutory; the affected individuals believe that they are being persecuted by another individual or group and have a fear of being harmed or harassed. This can commonly present with beliefs that one is being followed, that they are being stolen from, or that their food is being tampered with.

2. Hallucinations are the perception of sensory phenomena without an external stimulus. Hallucinations can occur in any sensory domain. The most common type seen in psychiatric illness is auditory hallucinations, which often consist of ≥1 familiar or unfamiliar voice. These voices are often derogatory in nature and can be distressing to the affected individual. Voices can also command patients to perform certain actions; most worrisome would be the command to harm themselves or others. Hallucinations occurring in other sensory domains (eg, visual hallucinations) are less common in patients with psychiatric illness. As such, nonauditory hallucinations should increase suspicion for an underlying secondary cause of psychotic illness (eg, delirium).

3. Disorganized speech reflects an impairment of cognitive organization that can affect individuals with psychosis and can manifest in their speech patterns. Disorganized thinking exists on a continuum from mild (eg, circumstantiality) to moderate (eg, tangentiality) to severe (eg, loosening of associations, word salad). In circumstantiality, affected patients provide more information than needed when answering a question, causing the conversation to drift off topic before providing an appropriate answer. In tangentiality, the conversation will deviate and not return to the specific question. In word salad, words and phrases appear random and unintelligible with no discernible connection.

4. Disorganized behavior, also known as abnormal motor behavior, can present in a multitude of manners. Examples include childlike “silliness” and unpredictable agitation. In its most severe form, patients can present with catatonic behavior. Catatonia is defined as a marked decrease or increase in reactivity to environment. Catatonia is heterogeneous in its presentation, as patients may display a variety of clinical features, such as negativism (ie, opposition to instruction), stupor, mutism, posturing, and agitation. While catatonia was historically associated with schizophrenia, it occurs more frequently in bipolar disorder. Note that the diagnosis and management of catatonia are outside the scope of this chapter.

5. Negative symptoms represent a lack or reduction of normal behaviors. Symptoms include anhedonia, avolition (ie, decreased motivation to engage in goal-directed behavior), alogia (ie, decreased speech), and reduced emotional expression (ie, blunted affect). While negative symptoms account for much of the functional impairment seen in patients with schizophrenia, they occur less frequently in other psychotic illnesses.

While not part of the diagnostic criteria, schizophrenia is associated with cognitive impairments in a number of domains. The most common impairments are seen in processing speed, attention, and working memory. Of note, cognitive impairments often present prior to the development of overt psychosis and are unlikely to improve with pharmacologic treatment.

DiagnosisTop

A summary of the DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders: Table 16.18-3.

The diagnosis of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders is multifactorial and often requires a multidisciplinary approach. It is important to note that no symptoms are pathognomonic for schizophrenia and that it is often a diagnosis of exclusion.

The following steps provide a framework to approaching patients with suspected psychotic symptoms:

1) Prior to assessment, ensure the immediate safety of the patient and others.

2) Focus on building rapport and avoid challenging the patient’s hallucinations and delusions.

3) Perform a thorough assessment, including a focus on:

a) Risk of harm to self or others.

b) Presence of comorbid psychiatric illness (eg, depression, anxiety).

c) Full mental status examination.

d) Past psychiatric history (noting previous admissions, pharmacologic treatments, and prior suicide attempts).

e) Forensic/legal history.

f) Thorough substance use history.

g) Past medical history.

h) Psychosocial history.

i) Current social functioning and supports.

4) Obtain collateral information, focusing on the topics discussed above.

5) Perform a neurologic examination if the patient is amenable.

6) Laboratory testing: Complete blood count (CBC), extended electrolytes (calcium, phosphate, magnesium), creatinine, liver-associated enzymes, albumin, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), vitamin B12, syphilis and hepatitis testing as indicated, urinalysis and a urine drug screen as indicated. Additional laboratory investigations (glucose, cortisol) may be performed based on one’s clinical index of suspicion.

7) Neuroimaging: Routine neuroimaging is not recommended.Evidence 1Weak recommendation (downsides likely outweigh benefits, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the small number of observational studies and indirectness (studies focusing on cost-effectiveness). Addington D, Abidi S, Garcia-Ortega I, Honer WG, Ismail Z. Canadian Guidelines for the Assessment and Diagnosis of Patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2017 Sep;62(9):594-603. doi: 10.1177/0706743717719899. Epub 2017 Jul 21. PMID: 28730847; PMCID: PMC5593247. Albon E, Tsourapas A, Frew E, et al. Structural neuroimaging in psychosis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2008 May;12(18):iii-iv, ix-163. doi: 10.3310/hta12180. PMID: 18462577. It is recommended only for patients exhibiting symptoms suggestive of an intracranial process (eg, seizures, focal neurologic deficits, rapid progression of memory deficits).

8) Neuropsychologic testing if available.

As with many other psychiatric diagnoses, psychotic disorder is often comorbid with other disorders, both psychiatric and systemic medical/neurologic. Schizophrenia often co-occurs with depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders. In terms of physical illnesses, individuals with schizophrenia often have diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. These illnesses are in turn associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and reduced life expectancy. Overall health is further impacted by high rates of nicotine use, sedentary lifestyle, and limited engagement in preventative medicine.

TreatmentTop

This section will focus on the treatment of acute psychotic episodes. Recommendations are drawn from the clinical guidelines on schizophrenia, as the body of information related to this form of psychosis is most robust. Regardless of the etiology, the following principles should underlie care throughout the course of the patient’s illness:

1) Treatment should be individualized. The choice of antipsychotic and psychosocial treatment should be a collaborative process between the physician and the patient or the substitute decision-maker (if the patient lacks decisional capacity).

2) The patient’s family, support system, or both should be actively involved in the treatment process, especially regarding the first episode of psychosis.

3) A rapid initiation of treatment is important, as longer duration of untreated psychoses is associated with a poorer prognosis.

4) The patient’s insight may fluctuate over time and can limit their capacity to make treatment decisions.

5) Regular assessment for and treatment of comorbidities (eg, depression, substance use disorders) are essential.

6) Routine monitoring and management of adverse effects are necessary.

7) Routine assessment of medication adherence is crucial.

8) Regular monitoring for aggressive behavior and suicidal ideation is essential (see Suicide Risk Assessment).

Antipsychotic medications are the mainstay of treatment for psychotic disorders. These medications can be effective at treating psychosis due to psychiatric or systemic medical/neurologic causes. Antipsychotics can be further subdivided into first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs). Notably, there is also a third generation of antipsychotics (TGAs), which include aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, and lumateperone. Commonly used antipsychotics, dose ranges, and notable adverse effects: Table 16.18-4.

1. Choosing an antipsychotic: With the exception of clozapine, there is no superiority for one antipsychotic over another. Further, there appears to be no significant difference among TGA, SGA, and FGA agents in regard to their effectiveness at treating positive symptoms (delusions and hallucinations). The SGA and TGA agents may be more effective at treating some negative symptoms.Evidence 2Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, indirectness (short duration of studies), and potential bias (industry sponsorship of many studies). Fusar-Poli P, Papanastasiou E, Stahl D, et al. Treatments of Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: Meta-Analysis of 168 Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials. Schizophr Bull. 2015 Jul;41(4):892-9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu170. Epub 2014 Dec 20. PMID: 25528757; PMCID: PMC4466178. Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li C, Davis JM. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009 Jan 3;373(9657):31-41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. Epub 2008 Dec 6. PMID: 19058842. While similar in their effectiveness, antipsychotics differ greatly in tolerability and their propensity for certain adverse effects. On balance, FGAs are generally associated with heightened risk of neurologic adverse effects (extrapyramidal symptoms [EPSs], discussed later in this chapter), whereas SGA agents are associated with increased risk of metabolic changes and weight gain. Compared with olanzapine or clozapine, the TGAs brexpiprazole, cariprazine, and lumateperone have shown a lower impact on metabolic parameters. Given the risk of EPSs and intolerability associated with FGAs, an SGA agent may be considered as first-line treatment.Evidence 3Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the short duration of studies and heterogeneity. Hunter RH, Joy CB, Kennedy E, Gilbody SM, Song F. Risperidone versus typical antipsychotic medication for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD000440. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000440. PMID: 12804396. Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li C, Davis JM. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009 Jan 3;373(9657):31-41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. Epub 2008 Dec 6. PMID: 19058842. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al; Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005 Sep 22;353(12):1209-23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. Epub 2005 Sep 19. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep 9;363(11):1092-3. PMID: 16172203. Barman R, Majumder P, Doifode T, Kablinger A. Newer antipsychotics: Brexpiprazole, cariprazine, and lumateperone: A pledge or another unkept promise? World J Psychiatry. 2021 Dec 19;11(12):1228-1238. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v11.i12.1228. PMID: 35070772; PMCID: PMC8717034.

Importantly, the choice of an agent may be limited by the route of administration, as acutely agitated patients may refuse oral options and require IM administration.

2. Dose: Once an agent is chosen and started, it should be titrated up to a therapeutic dose over the period of several days to a week. This speed of titration is often mediated by tolerability. Improvement should be seen within 2 weeks on an effective dose, and absence of improvement is a predictor for nonresponse. If a response is not seen at 2 weeks, the dose can be titrated further as tolerated. If no response is seen after additional 2 weeks, a switch to an alternative antipsychotic should be considered. An adequate trial is considered 4 to 6 weeks on a therapeutic dose.

Antipsychotics should be prescribed at the lowest effective dose, especially in antipsychotic-naive patients. However, higher does may be needed for acute agitation.

3. Switching antipsychotics: If the first antipsychotic is ineffective or intolerable, a switch to an alternative agent should be considered.

No clear guidelines or protocols exist for switching antipsychotics. In general, medications can be switched by cross-titration, in that one medication is slowly tapered while the newer agent is titrated in proportional amounts. Alternatively, if the risk of relapse is a concern, a new agent could be titrated up to a therapeutic dose before the previous antipsychotic is tapered. Antipsychotics should always be discontinued gradually to avoid the occurrence of cholinergic rebound as well as the emergence of dyskinesia, which can occur with rapid dose reduction or discontinuation.

4. Duration of treatment: The length of treatment is dependent on the suspected etiology. In the case of a first psychotic episode in schizophrenia, antipsychotics should be considered for ≥1.5 years following the remittance of symptoms. A minimum duration of 5 years should be considered following resolution of symptoms in a patient with schizophrenia who had multiple psychotic episodes. For psychoses secondary to a systemic medical condition or medication/substances, treatment with an antipsychotic may only be required until the acute precipitant has resolved.

5. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics: Several antipsychotics are available in long-acting injectable formulations, with dosing frequency ranging from every 2 weeks to every 3 months. Long-acting injectables can be used to mitigate nonadherence and in the case of schizophrenia should be offered at any stage of illness.

6. Additional pharmacologic strategies: As stated previously, psychosis can be secondary to a heterogeneous group of illnesses. As such, employment of other psychotropic medications is often needed:

1) Benzodiazepines are employed in the management of acute agitation, sleep disturbance, and anxiety (see The Agitated Patient).

2) Antidepressants are often implemented in the treatment of comorbid depressive symptoms, anxiety disorder, or schizoaffective disorder.

3) Mood stabilizers (lithium and anticonvulsants) are combined with antipsychotics in the management of treatment-resistant schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type.

7. Treatment setting: Inpatient treatment is recommended for patients with agitation, aggressive behaviors, severe symptoms, and suicidality. Admission may also be required for patients with substance intoxication, substance withdrawal, or comorbid acute physical illness. Involuntary admission is required when there is a risk of harm to self or others or if the patient is at risk of indirect harm due to inability to care for self.

Outpatient treatment occurs in a number of settings. Patients with a first episode of psychosis should be referred to an early intervention clinic or a local psychiatry center specializing in psychotic disorders. Patients with chronic illness can be referred to a schizophrenia outpatient clinic. The most intensive level of care is offered through assertive community treatment (ACT) teams, which offer care to individuals with severe forms of psychosis who are often impacted by medication nonadherence, comorbid substance use, tenuous housing, repeat hospital admissions, and significant functional impairment.

8. Treatment resistance: Treatment resistance is defined as persistence of severe symptoms and functional impairment despite 2 antipsychotics trials of ≥6 weeks at a therapeutic dose. Clozapine is superior to other antipsychotic agents in regard to treatment of positive symptoms (delusions and hallucinations) and is indicated in the management of treatment-resistant schizophrenia.Evidence 4Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness (short duration of studies) and heterogeneity. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al; CATIE Investigators. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Apr;163(4):600-10. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.600. PMID: 16585434. Lewis SW, Barnes TR, Davies L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of effect of prescription of clozapine versus other second-generation antipsychotic drugs in resistant schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2006 Oct;32(4):715-23. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj067. Epub 2006 Mar 15. PMID: 16540702; PMCID: PMC2632262. Siskind D, McCartney L, Goldschlager R, Kisely S. Clozapine v. first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2016 Nov;209(5):385-392. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177261. Epub 2016 Jul 7. PMID: 27388573. However, while effective, clozapine is associated with a number of significant adverse effects (Table 16.18-5). Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in combination with antipsychotics could also be considered in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

9. High-dose strategies and antipsychotic polypharmacy: With the exception of certain circumstances, antipsychotics should not be prescribed at doses exceeding the maximum range as stipulated in the product monograph. Circumstances requiring higher doses would include treatment of aggressive behavior that poses a risk to the patient or others. In addition, the combination of multiple antipsychotics is discouraged outside of certain scenarios.

While pharmacotherapy is the mainstay of treatment, psychosocial modalities offer unique and complementary approaches. It should be noted that psychosocial treatments alone are not sufficient for the effective treatment of acute psychosis.

1. Psychoeducation/family-based interventions: Negative familial relationships have been associated with increased risk of relapse. Family-based interventions attempt to prevent this by providing family members with education on the diagnosis of psychosis, treatment, course of illness, and prognosis. Family members should be provided with information regarding the risks associated with medication nonadherence, comorbidity between psychosis and substance use disorders, and early symptoms and signs that could indicate a relapse. Family-based interventions also involve the development of communication and problem-solving skills to avoid maladaptive interactions. Family intervention should be provided in structured sessions, with ≥10 sessions over a 3-month period. This is indicated for all patients.Evidence 5Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the unclear risk of bias. Pharoah F, Mari J, Rathbone J, Wong W. Family intervention for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Dec 8;(12):CD000088. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000088.pub2. PMID: 21154340; PMCID: PMC4204509. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Schizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Primary and Secondary Care (Update) [Internet]. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society; 2009 Mar. PMID: 20704054. Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychol Med. 2002 Jul;32(5):763-82. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005895. PMID: 12171372.

2. Cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis (CBTp) targets positive symptoms of psychosis with the goal of reducing the severity of delusions and hallucinations that remain resistant to pharmacotherapy. CBTp involves the use of cognitive and behavioral interventions allowing patients to develop a new understanding of their symptoms and reduce associated distress. A minimum dose of 16 sessions is recommended. This is indicated for patients with residual symptoms despite treatment with an antipsychotic at a therapeutic dose.Evidence 6Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, imprecision, and potential bias. Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychol Med. 2002 Jul;32(5):763-82. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005895. PMID: 12171372. Jones C, Hacker D, Meaden A, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy plus standard care versus standard care plus other psychosocial treatments for people with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Nov 15;11(11):CD008712. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008712.pub3. PMID: 30480760; PMCID: PMC6516879.

3. Vocational rehabilitation includes various interventions such as supported employment programs and prevocational skills training. This is indicated for patients with a desire to return to work who are experiencing associated difficulties in this regard.Evidence 7Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, indirectness (short duration of studies), and potential bias. Kinoshita Y, Furukawa TA, Kinoshita K, et al. Supported employment for adults with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Sep 13;2013(9):CD008297. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008297.pub2. PMID: 24030739; PMCID: PMC7433300. Twamley EW, Jeste DV, Lehman AF. Vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: a literature review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003 Aug;191(8):515-23. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000082213.42509.69. PMID: 12972854.

4. Social skills training employs various behavioral techniques to reduce deficits in skills related to social interactions (eg, communication skills, developing friendships). Techniques include role playing, modeling, rehearsal, positive feedback, and corrective instructions. This is indicated for patients experiencing distress related to social interactions.Evidence 8Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, small sample size, and potential bias. Almerie MQ, Okba Al Marhi M, Jawoosh M, et al. Social skills programmes for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jun 9;2015(6):CD009006. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009006.pub2. PMID: 26059249; PMCID: PMC7033904. Kurtz MM, Mueser KT. A meta-analysis of controlled research on social skills training for schizophrenia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008 Jun;76(3):491-504. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.491. PMID: 18540742.

5. Cognitive remediation aims to improve impairment in commonly affected domains such as attention, memory, and executive function. This is indicated for patients with persistent and subjectively distressing cognitive deficits.Evidence 9Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, small sample sizes, and potential bias. Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, McGurk SR, Czobor P. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: methodology and effect sizes. Am J Psychiatry. 2011 May;168(5):472-85. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060855. Epub 2011 Mar 15. PMID: 21406461. Turner DT, van der Gaag M, Karyotaki E, Cuijpers P. Psychological interventions for psychosis: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2014 May;171(5):523-38. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13081159. PMID: 24525715.

As noted (Table 16.18-4), antipsychotics are associated with a number of adverse effects, including EPSs, cardiac effects, and metabolic changes. It is recommended that patients be monitored for these negative outcomes on a routine basis.

Prior to starting an antipsychotic, the following baseline tests should be completed: height and weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, electrocardiography, glucose screening, lipid profile, prolactin level.

Once an antipsychotic has been started, the following monitoring schedule is strongly recommended:

1) Weight: Measured weekly for the first 6 weeks, then at 12 weeks, at 1 year, and then annually.

2) Waist circumference: Annually.

3) Blood pressure: At 12 weeks, at 1 year, and then annually.

4) Glucose screening: At 12 weeks, at 1 year, and then annually.

In terms of EPSs, patients should be monitored on a weekly basis for 2 weeks when starting a new medication or following dose increases.

The Tool for Monitoring Antipsychotic Side Effects (TMAS) is a Canada-developed tool that can be used to monitor a range of adverse effects. It is freely available at epicanada.org. Other commonly used scales include the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) and Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS).

Antipsychotics are associated with a wide range of adverse effects. Detection and management of these adverse outcomes is crucial, because intolerability may be associated with medication nonadherence, which is in turn linked to the risk of relapse.

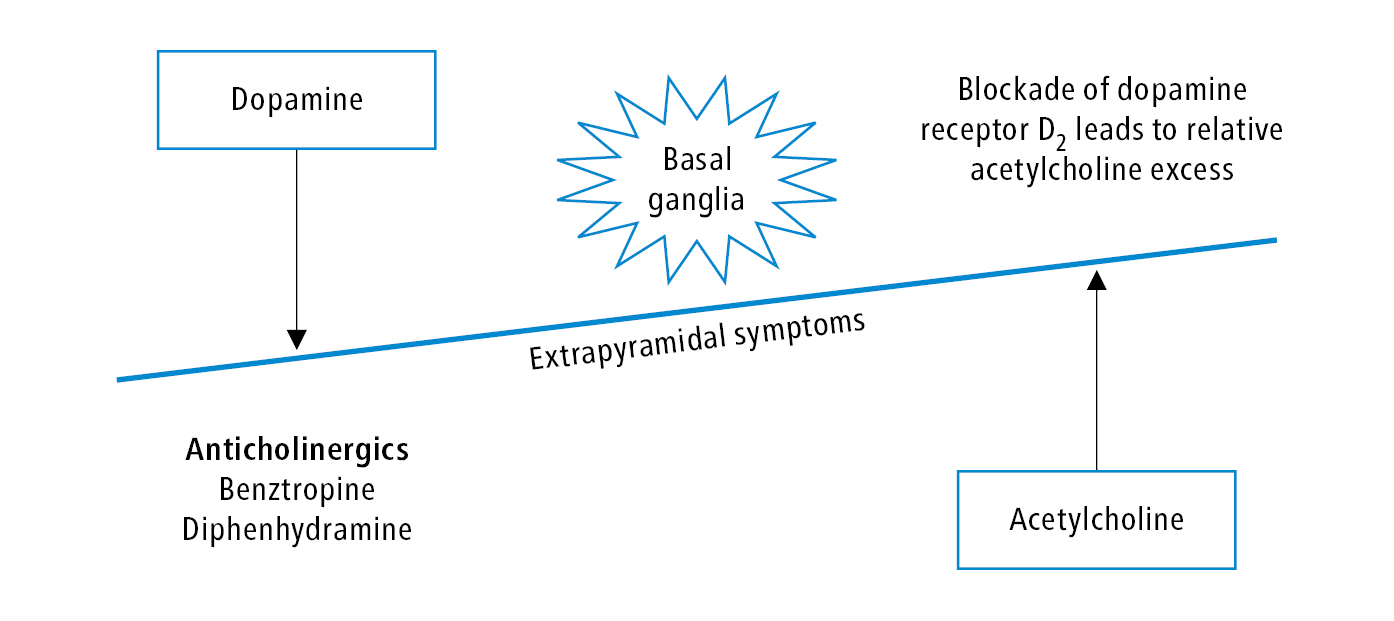

1. EPSs: A group of adverse effects including parkinsonism, akathisia, acute dystonia, and tardive dyskinesia (Table 16.18-6). The risk of each outcome is dependent on the specific antipsychotic, with FGAs generally possessing a greater risk. EPSs and the dopamine-acetylcholine interaction: Figure 16.18-1.

1) Parkinsonism typically occurs days to weeks after starting an antipsychotic or dose increase. It presents with tremor, cogwheel rigidity, shuffling gait, masklike facial expression, and bradykinesia. As a first step in treatment, consider a reduction in dose or a switch to an SGA or low-potency FGA. If this is not possible, antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism can be treated with an anticholinergic agent such as benztropine, starting at a dose of 1 mg once daily or bid.

2) Akathisia typically occurs hours to days after starting an antipsychotic or dose increase. It is defined as a state of agitation and inner restlessness. Patients present with an inability to stay still (pacing, fidgeting). As a first step in treatment, consider a reduction in dose or a switch to an antipsychotic with less propensity for akathisia. If this is not possible, consider treatment with propranolol, starting at 10 mg bid.

3) Acute dystonia typically occurs within hours or days of starting an antipsychotic or dose increase. It presents as involuntary muscular contractions or postures. Presentations include torticollis, oculogyric crisis (eyes rolling upwards), or laryngospasm. Laryngospasm is a medical emergency and should be treated immediately with IM or IV benztropine 1 to 2 mg. Outside of this emergent period, dystonia can be treated by a reduction in dose or a switch to an SGA or a low-potency FGA. If this is not possible, ongoing treatment with benztropine may be needed.

4) Tardive dyskinesia occurs following chronic treatment with an antipsychotic (ie, months to years). It presents as involuntary and repetitive movements, such as choreoathetoid movements of the tongue, extremities, and trunk, but it can also manifest as grimacing, lip smacking, and chewing. Treatment is often limited, with the best evidence for switching to clozapine, although the risk-benefit balance must be taken into account. There are 2 medications approved in the recent years by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat tardive dyskinesia: valbenazine and deutetrabenazine.

2. Hyperprolactinemia presents with menstrual disturbances, galactorrhea, sexual dysfunction, and gynecomastia in men. Chronic elevations in prolactin levels may lead to reduced bone mineral density. It is most often associated with risperidone or paliperidone and can be treated by switching antipsychotics. If this is not feasible, augmentation with aripiprazole (a dopamine partial agonist) can be effective at reducing prolactin levels.

3. Metabolic adverse effects: The risk of metabolic changes (ie, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia) and weight gain is dependent on the specific antipsychotic. As a first step, patients should be encouraged to engage in practices that promote positive cardiovascular and metabolic health (smoking cessation, physical activity, optimizing diet). It is recommended that mental health programs provide patients with access to education and resources to aid with diet and physical activity. Health professionals such as occupational therapists and dieticians can be instrumental in this regard.

If the above is ineffective, a trial of metformin should be considered to promote weight loss and reduce the risk of developing diabetes mellitus.Evidence 10Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness (short duration of studies, unclear if results are generalizable). Siskind DJ, Leung J, Russell AW, Wysoczanski D, Kisely S. Metformin for Clozapine Associated Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 15;11(6):e0156208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156208. PMID: 27304831; PMCID: PMC4909277. Zheng W, Li XB, Tang YL, Xiang YQ, Wang CY, de Leon J. Metformin for Weight Gain and Metabolic Abnormalities Associated With Antipsychotic Treatment: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015 Oct;35(5):499-509. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000392. PMID: 26280837.

If weight gain or metabolic changes are intolerable to the patient or result in excessive harm, consideration could be given to switching to a more weight-neutral medication (eg, aripiprazole, ziprasidone, haloperidol).

Otherwise, the management of metabolic changes and weight gain in this patient population is in line with primary care guidelines.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Autoimmune |

SLE, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis |

|

Endocrine and metabolic |

Hyperthyroidism/hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism/hypoparathyroidism, hypercalcemia, vitamin B12/vitamin D deficiency, Wilson disease, hepatic and uremic encephalopathy |

|

Infectious |

HIV, syphilis |

|

Neurodegenerative |

Parkinson disease, Lewy body dementia, Alzheimer disease, Huntington disease |

|

Neurologic |

Stroke, hemorrhage, space-occupying lesion, temporal lobe epilepsy, multiple sclerosis |

|

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus. |

|

|

Analgesic |

Opioids, NSAIDs |

|

Anesthetic |

Ketamine |

|

Antibiotic |

Isoniazid, ethambutol, fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins |

|

Anticholinergic |

Atropine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl, scopolamine |

|

Antiepileptic |

Zonisamide |

|

Antimalarial |

Mefloquine, chloroquine |

|

Antiviral |

Acyclovir, ganciclovir, efavirenz, nevirapine |

|

Antiparkinsonian |

Pramipexole, ropinirole, amantadine, selegiline, levodopa |

|

Cardiovascular |

Digoxin, quinidine, procainamide, beta-blockers |

|

Drugs of abuse |

Alcohol, benzodiazepines, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, MDMA, LSD, opioids |

|

Glucocorticoids |

Prednisone, dexamethasone |

|

Interferon |

Interferon alpha |

|

Muscle relaxants |

Baclofen |

|

OTC |

Dextromethorphan, antihistamines |

|

LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OTC, over the counter. | |

|

Criterion A symptoms: (1) delusions; (2) hallucinations; (3) disorganized speech; (4) disorganized or catatonic behavior; (5) negative symptom |

|

Schizophrenia: – ≥2 criterion A symptoms present; ≥1 must be (1), (2), or (3) – Duration of acute phase: ≥1 month (or <1 month if successfully treated) – Duration of illness: ≥6 months – Specifier: First episode, currently in acute episode/partial remission/full remission; multiple episodes, currently in acute episode/partial remission/full remission; continuous; unspecified |

|

Schizoaffective disorder: – Criterion A (1) or (2) symptom present for ≥2 weeks in the absence of a major mood episode during the lifetime duration of illness – Criterion A (as above) concurrent with a major mood episode (depressive or manic); a major mood episode present for the majority of the total duration of active and residual portions of illness – Specifier: Bipolar type, depressive type |

|

Schizophreniform disorder: – ≥2 criterion A symptoms present; ≥1 must be (1), (2), or (3) – Duration of acute phase: ≥1 month – Duration of illness: <6 months – Specifier: With/without good prognostic features |

|

Brief psychotic disorder: – ≥1 of criterion A symptoms (1), (2), (3), or (4) – ≥1 must be (1), (2), or (3) – Duration: ≤1 month; full resolution of symptoms and return to premorbid functioning level – Specifier: With/without marked stressor(s), with postpartum onset |

|

Delusional disorder: – ≥1 delusions – Other criterion A symptoms not met (if present, hallucinations are not prominent and related to delusional theme) – If present, manic or major depressive episodes are brief relative to the duration of illness – Duration of illness: ≥1 month – Specifier: Erotomanic type, grandiose type, jealous type, persecutory type, somatic type, mixed type |

|

Substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder: – ≥1 of criterion A symptoms (1) or (2) – Criterion A symptoms occur during or soon after substance intoxication or withdrawal or after exposure to medication – Substance/medication is capable of producing criterion A symptoms; not occurring exclusively during delirium – Specifier: With onset during intoxication, with onset during withdrawal |

|

DSM-5-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision. |

|

Initial dose (mg/d) |

Usual therapeutic dose range (mg/d) |

Notable adverse effects |

|

|

First-generation antipsychotics |

|||

|

Haloperidol (high potency) PO, IM, IV, LAI |

1-2 |

2-10 |

– EPSs – QTc prolongation – Hyperprolactinemia |

|

Perphenazine (mid potency) PO |

4-8 |

12-24 |

– EPS (less than haloperidol) – Sedation (less than CPZ) – Weight gain (less than CPZ) – Anticholinergic (less than CPZ) – Orthostatic hypotension (less than CPZ) |

|

Chlorpromazine (CPZ) (low potency) PO |

25-50 |

300-600 |

– Sedation – Weight gain – Anticholinergic – Orthostatic hypotension – QTc prolongation – Impaired glucose metabolism |

|

Second- and third-generation antipsychotics |

|||

|

Risperidone PO, ODT, LAI |

0.5-1 |

2-8 |

– EPSs – Hyperprolactinemia – Weight gain – Sedation – Impaired glucose metabolism |

|

Olanzapine PO, ODT, IM |

2.5-5 |

5-20 |

– Weight gain – Sedation – Dyslipidemia – Impaired glucose metabolism |

|

Quetiapine PO |

25-50 |

400-800 |

– Weight gain – Sedation – Dyslipidemia – Impaired glucose metabolism – Orthostatic hypotension |

|

Aripiprazole PO, LAI |

2-5 |

10-30 |

Akathisia |

|

Brexpiprazole PO |

0.5-1 |

2-4 |

– Akathisia, tremor – Somnolence – Weight gain |

|

Cariprazine PO |

1.5 |

1.5-6 |

– EPSs – Insomnia – Weight gain |

|

Lumateperone PO |

42 |

42 (dose titration not required) |

– EPSs – Sedation, somnolence – Weight gain |

|

Pimavanserin (indicated for Parkinson disease psychosis) PO |

34 (capsules) 10 (tablets) |

34 (capsules) 10 (tablets) (dose titration not required) |

– Nausea, constipation – Peripheral edema – Gait disturbances |

|

EPS, extrapyramidal symptom; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; LAI, long-acting injectable; ODT, orally dissolving/disintegrating tablet; PO, oral. |

|||

|

– Sedation – Weight gain – Metabolic changes (glucose and lipid metabolism) – Anticholinergic effects (eg, dry mouth, urinary retention, constipation) – Sialorrhea – Orthostatic hypotension – Agranulocytosis – Myocarditis – Cardiomyopathy – Seizure |

|

Adverse effect |

Onset |

Clinical features |

|

Parkinsonism |

Days to weeks |

Tremor, shuffling gait, drooling, stooped posture |

|

Akathisia |

Hours to days |

Agitation, inner restlessness, pacing, fidgeting |

|

Acute dystonia |

Hours to days |

Torticollis, oculogyric crisis, laryngospasm |

|

Tardive dyskinesia |

Months to years |

Choreoathetoid movements of tongue, extremities, and trunk; grimacing; lip smacking; chewing |

Figure 16.18-1. Extrapyramidal symptoms and the dopamine-acetylcholine interaction. When extrapyramidal symptoms occur, a striatal dopaminergic-cholinergic neurotransmitter imbalance appears due to the blockade of the D2 receptor in the extrapyramidal system.