Chen TJ, Traynor V, Wang AY, et al. Comparative effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for preventing delirium in critically ill adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022 Jul;131:104239. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104239. Epub 2022 Mar 28. PMID: 35468538.

Burton JK, Craig LE, Yong SQ, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Jul 19;7(7):CD013307. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013307.pub2. PMID: 34280303; PMCID: PMC8407051.

Oh ES, Needham DM, Nikooie R, et al. Antipsychotics for Preventing Delirium in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1;171(7):474-484. doi: 10.7326/M19-1859. Epub 2019 Sep 3. PMID: 31476766.

American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Postoperative Delirium in Older Adults. American Geriatrics Society abstracted clinical practice guideline for postoperative delirium in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 Jan;63(1):142-50. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13281. Epub 2014 Dec 12. PubMed PMID: 25495432; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5901697.

Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014 Mar 8;383(9920):911-22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1. Epub 2013 Aug 28. Review. PubMed PMID: 23992774; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4120864.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Inouye SK, Fearing MA, Marcantonio ER. Delirium. In: Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti M, Studenski S, High KP, Asthana S, eds. Hazzard’s Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2009: 647-658.

Liptzin B, Levkoff SE, Gottlieb GL, Johnson JC. Delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993 Spring;5(2):154-60. Review. PubMed PMID: 8508034.

Liptzin B, Levkoff SE. An empirical study of delirium subtypes. Br J Psychiatry. 1992 Dec;161:843-5. PubMed PMID: 1483173.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Delirium is an acute clinical syndrome characterized by fluctuating confusion, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered levels of consciousness. Affecting up to 50% of hospitalized seniors and up to 90% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients, it is a common and important cause of patient morbidity and mortality, including those in emergency department, general medical, ICU, surgical, oncology, and palliative care settings. In fact, it is the most common complication of hospitalization for older adults.

Although preventable in 30% to 40% of cases,Evidence 1Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias. Siddiqi N, Harrison JK, Clegg A, et al. Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Mar 11;3:CD005563. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005563.pub3. Review. PubMed PMID: 26967259. delirium can lead to significant short-term and long-term consequences, including accelerated cognitive and functional decline, increased hospital length of stay, institutionalization, and death. The impact of delirium on health-care systems is profound, with hundreds of billions of annual health-care costs attributed directly to delirium. Prevention is critical as delirium can take weeks to months for resolution. A moderate-quality systematic review of hospitalized patients showed that persistent delirium was still present in 44.7% at discharge and in 21% at 6 months postdischarge.Evidence 2Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. Cole MG, Ciampi A, Belzile E, Zhong L. Persistent delirium in older hospital patients: a systematic review of frequency and prognosis. Age Ageing. 2009 Jan;38(1):19-26. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn253. Epub 2008 Nov 18. Review. PubMed PMID: 19017678.

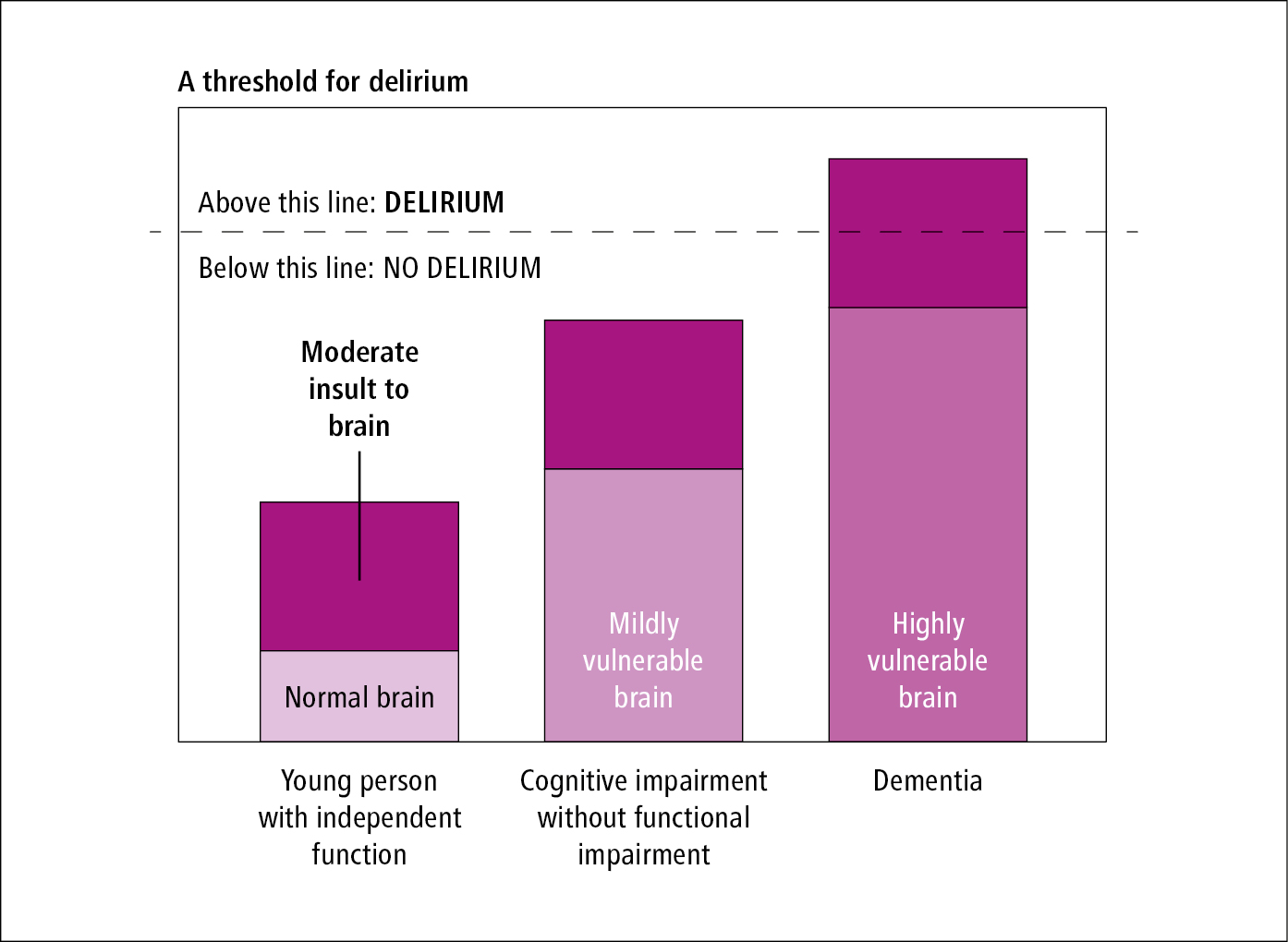

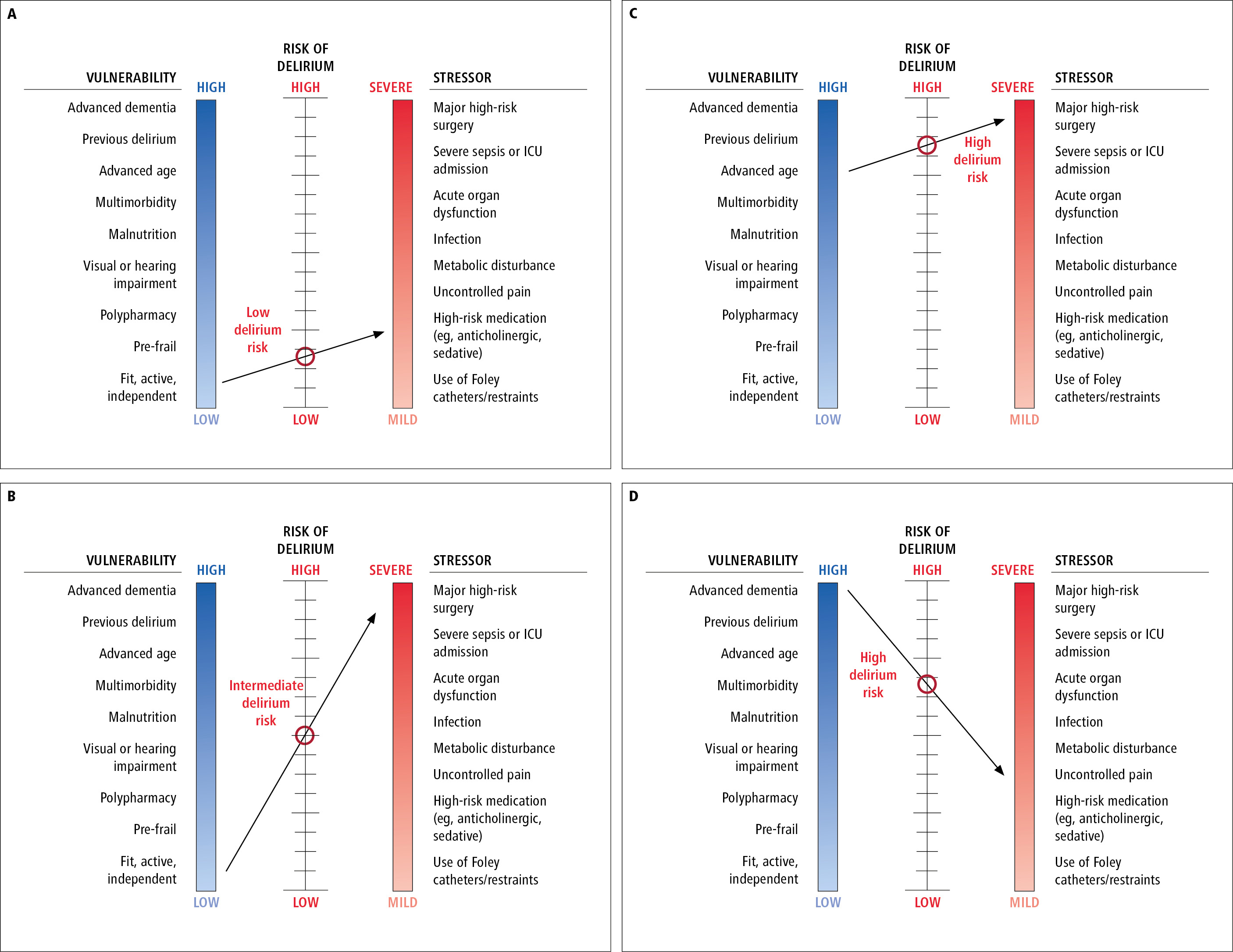

Although a single factor can precipitate delirium, the etiology is usually multifactorial. Evidence of a medical cause can usually be elucidated through focused history, physical examination, and diagnostic investigations. Common predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium: Table 16.8-1. Delirium development is dependent on complex interactions between the patient’s baseline vulnerability for delirium (based on predisposing risk factors) and their exposure to precipitating factors or noxious insults (Figure 16.8-1, Figure 16.8-2). Precipitants alone do not usually cause delirium. Delirium occurs when the stress associated with the precipitant/insult exceeds the brain’s reserve to compensate and maintain normal functioning. As a result, a small insult might be enough to precipitate delirium in a frail older adult with multiple morbidities, while a combination of large insults may be necessary in a younger healthier individual.

The mnemonic “DELIRIUM Plus” is a useful way of considering the various etiologies in the differential diagnosis of delirium that may be contributing to its onset (Table 16.8-2).

Clinically, the implications of a multifactorial etiology are 2-fold: (1) identifying and addressing the specific underlying cause or causes in each case is important; and (2) multicomponent strategies for preventing delirium are more likely to be effective.

High-risk drug use is an important predisposing risk factor and precipitant for delirium. There is a large list of drugs and their metabolites that precipitate delirium, but the most common ones are those with known psychotropic or anticholinergic effects (Table 16.8-3). Studies have shown that use of 2 or more psychotropics and starting 3 or more drugs lead to a 4.5-fold and 3.9-fold increased relative risk of delirium, respectively.

The pathophysiology of delirium is poorly understood. There are several proposed hypotheses, but accumulating evidence suggests that there are likely multiple interacting factors disrupting normal neuronal brain function. Delirium appears to be the final common pathway and expression of multiple different pathologies that disrupt multiple brain regions and neurotransmitter systems. These include, but are not limited to, altered neurotransmission due to cholinergic deficiency and/or dopamine excess, stress-induced inflammation and cytokine release, cerebral hypoxia, disturbances in tryptophan metabolism, chronic physiological stress (eg, hypercortisolism) and genetic factors (eg, apolipoprotein E genotype variance leading to disturbance of normal physiological processes). Different mechanisms may be more prominent depending on the circumstance (eg, postoperative, ICU, general medical illness).

Clinical FeaturesTop

The cardinal features of delirium are an acute onset and fluctuating course of disorganized thinking or disturbances in consciousness with poor attention. Other supporting features include disorientation, memory impairment, perceptual disturbances (hallucinations, illusions, misperceptions), delusions, psychomotor agitation or retardation, and sleep-wake cycle disturbances. Physical signs such as asterixis (flapping of outstretched, dorsiflexed hand), multifocal myoclonus (nonrhythmic, asynchronous muscle jerking), carphologia (involuntary picking or grasping of real or imaginary objects), and postural action tremor can often be observed in metabolic and toxic delirium.

Similar to dementia, responsive behaviors are common. These behaviors are actions, words, and gestures that are expressed by patients in response to unmet needs or stimuli (perceived or real) in their personal, social, or physical environment. Due to effects of delirium on memory, judgement, orientation, mood, and behavior, they often manifest as restlessness, frustration, distress, anxiety, calling out, getting lost, or sexual behavior.

Three clinical delirium subtypes have been recognized: hypoactive, hyperactive, and mixed. Hypoactive delirium is characterized by features such as lethargy and excess somnolence, while hyperactive delirium is characterized by features such as pacing, hallucinations, and other responsive behaviors. Fluctuations between hypoactive and hyperactive features indicate a mixed delirium.

Although hypoactive delirium is more common in older adults and associated with worse outcomes including an increased risk of mortality, it is less likely to be recognized. In contrast to the responsive behaviors of hyperactive delirium, hypoactive delirium does not readily attract the extra attention of clinicians. For delirium to be detected, clinicians need to have a high degree of suspicion and patients need to be actively engaged and examined.

“Subsyndromal delirium” has also been described in patients who demonstrate some but not all of the cardinal features of delirium. Although not well defined or studied, subsyndromal delirium is prognostically important with outcomes shown to be intermediate between those in full delirium and no delirium.

DiagnosisTop

Delirium is a clinical diagnosis. There is currently no established diagnostic test or biomarker and diagnosis often requires focused clinical observation, history taking, and cognitive testing. As a result, delirium is often missed and goes undetected in >50% of patients. Timely detection is critical because delirium is a potential medical emergency. Delayed or missed diagnosis has been associated with a 7-fold increased risk for mortality.

The reference standard for the diagnosis of delirium has typically been defined by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. According to the 5th edition (DSM-5), delirium is diagnosed by 5 key features:

1) A disturbance in attention (reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain, and shift attention) and awareness.

2) The disturbance develops over a short period of time (usually hours to days), represents a change from baseline, and tends to fluctuate during the course of the day.

3) An additional disturbance in cognition (memory deficit, disorientation, language, visuospatial ability, or perception).

4) The disturbances are not better explained by another preexisting, evolving, or established neurocognitive disorder and do not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma.

5) There is evidence from history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is caused by a medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, or adverse effects of medications.

A formal diagnosis using this reference standard typically involves an in-depth patient interview and cognitive testing by an experienced clinician.

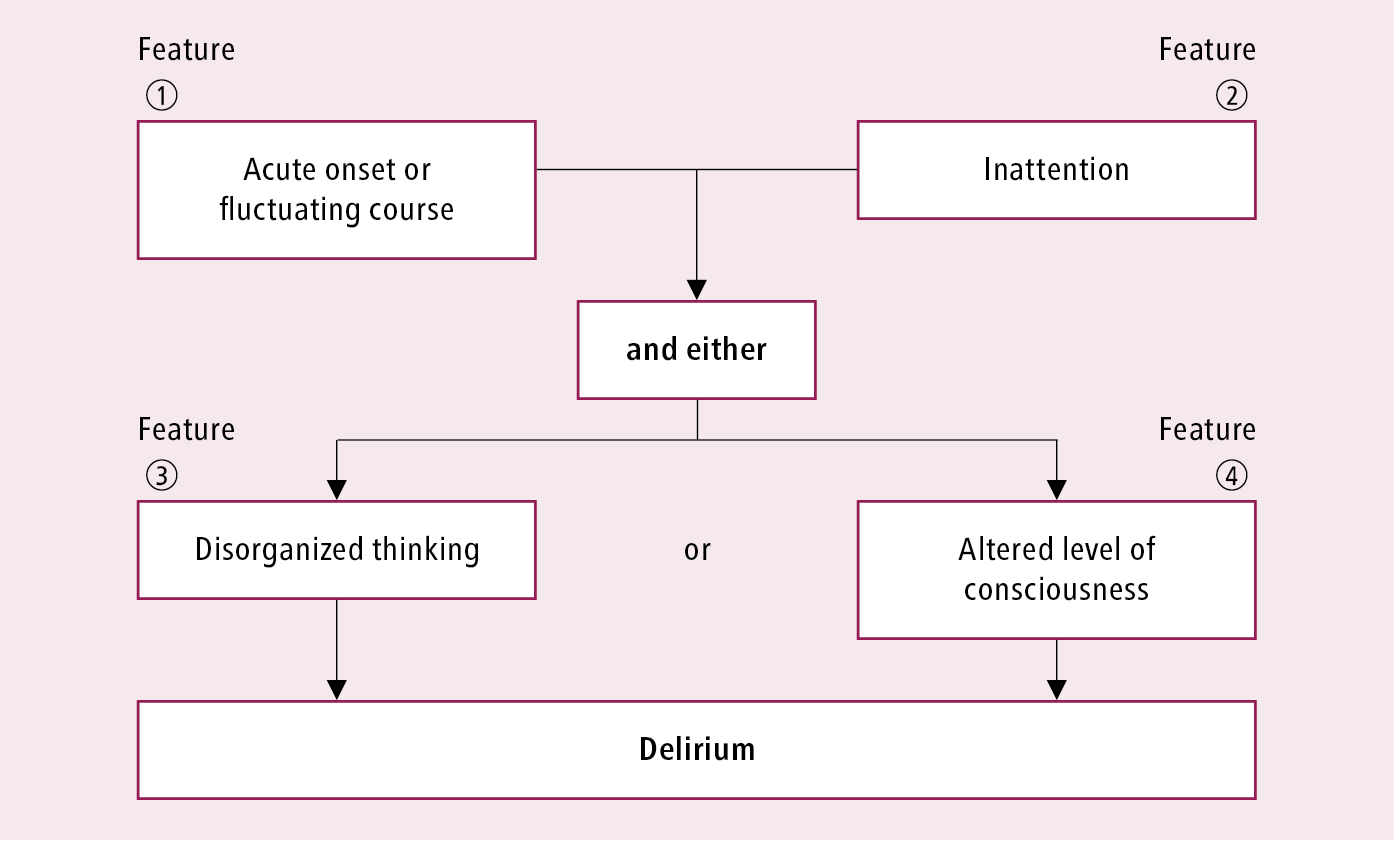

Several bedside screening and diagnostic instruments have been developed to improve identification and better guide which patients should receive formal consultation and intervention. Recent systematic reviews suggest the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) has the best evidence to support its use. Taking 5 minutes to administer and available at www.help.agscocare.org, the CAM has a sensitivity of 94% to 100%, specificity of 90% to 95%, positive likelihood ratio of 9.6, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.16 for diagnosing delirium.Evidence 3Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias. Wong CL, Holroyd-Leduc J, Simel DL, Straus SE. Does this patient have delirium?: value of bedside instruments. JAMA. 2010 Aug 18;304(7):779-86. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1182. Review. PubMed PMID: 20716741. It identifies 4 delirium features: acute onset or fluctuating course, inattention, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness. The diagnosis of delirium requires the presence of features 1 and 2 with either feature 3 or 4 (Figure 16.8-3).

The CAM has become the most widely used instrument for clinical and research purposes and it performs well in emergency department, postoperative, and mixed inpatient settings. It has also been adapted for use in nonverbal or intubated patients in the form of the CAM-ICU.Evidence 4Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med. 2001 Jul;29(7):1370-9. PubMed PMID: 11445689. However, specific training is recommended to ensure optimum performance.

A common clinical challenge is differentiating delirium from dementia, given some overlapping symptoms and strong associations with each other. Delirium is associated with an increased risk of developing dementia, and dementia is associated with an increased risk of developing delirium. Delirium and dementia commonly coexist for these reasons. Dementia with Lewy bodies is particularly difficult to distinguish, given that it has features of both delirium and dementia. The key feature that helps to distinguish delirium from dementia is the time course of its presentation and progression. Delirium typically has an acute and rapid onset, whereas dementia almost always progresses more gradually. Evidence-based tools for detecting delirium superimposed on dementia are very limited, although some existing tools show promise, including the CAM, CAM-ICU, and the 4 A’s test (4AT).

The 4AT, available at www.the4at.com, consists of 4 items that take 2 to 3 minutes to administer: 2 brief cognitive tests and assessments of level of consciousness and acute changes in mental status. A systematic review has shown a pooled sensitivity of 0.88 (95% CI, 0.80-0.93) and pooled specificity of 0.88 (95% CI, 0.82-0.92). In patients with dementia, reported sensitivity and specificity range from 0.86 to 0.94 and 0.65 to 0.79, respectively.Evidence 5Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. Tieges Z, Maclullich AMJ, Anand A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the 4AT for delirium detection in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2021 May 5;50(3):733-743. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa224. PMID: 33951145; PMCID: PMC8099016. The reported advantages of the 4AT are ease and speed of use without requiring specific operator training.

ManagementTop

The mainstay of delirium management is reversal of the underlying cause and prevention of its complications. Pharmacologic treatment should only be considered in circumstances where patients are at risk of harming themselves or others.

Treatment of the Underlying Cause

Reviewing the patient’s medical history, physical examination, medications, and laboratory investigations usually points to one or more causes of delirium. Common causes: Table 16.8-4.

After treating the underlying cause of delirium, nonpharmacologic strategies should be instituted to prevent worsening delirium (see below), relieve symptoms, and reduce complications. Nonpharmacologic measures are also used to prevent injuries to the patient and others. The following strategies should be used:

1) Familiar faces and environment can often alleviate responsive behaviors in a delirious patient. We recommend informing family members and other caregivers when a patient is agitated and offer them a chance to comfort the patient, either in person, by phone, or other means (eg, online video chat). We also recommend putting familiar pictures and belongings (eg, pillows, blankets, photographs) in the patient’s room.

2) Validation is a technique used to explore and comfort patients with confusion. For example, older patients with delirium will sometimes ask for their parents, who are often deceased. Instead of confronting them with the truth, it is often helpful to explore their disorientation and validate their fears. Validation is often used in dementia but it can be applied to delirium as well. More details available at vfvalidation.org.

3) De-escalation and redirection are important techniques when encountering an agitated patient. Attending a local training course is recommended. Programs such as Gentle Persuasive Approach (www.ageinc.ca/GPA/basics.html) is an example from the Advanced Gerontological Education based in Hamilton, Canada.

4) A sitter is a trained staff (either health-care professional or volunteer) or family member who provides constant observation for patients in delirium. Sitters should be actively engaged in the patient’s care and not just passively observing. Sitters provides care (eg, hydration, toileting, reorientation) and can alert health-care staff about imminent dangers (eg, falls, wandering) at the bedside in a timely manner. Although there are associated costs, sitters can prevent complications of delirium, reduce physical restraint use, and potentially avoid longer lengths of stay in acute care. We recommend a sitter providing constant observation to patients in delirium, particularly those with hyperactive subtype.

5) Physical restraints should be avoided unless all possible measures have failed and imminent harm to self and others is likely. Restraints are associated with worsening of delirium, falls, serious injuries, increased length of stay, and death.Evidence 6Weak recommendation (downsides likely outweigh benefits, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the observational nature of data. Evans D, Wood J, Lambert L. Patient injury and physical restraint devices: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2003 Feb;41(3):274-82. Review. PubMed PMID: 12581115. We recommend expert consultation (eg, geriatric medicine, psychiatry specialists, other clinician specialists in geriatrics) when physical restraint use is unavoidable in a delirious patient.

Assuming that the underlying cause of delirium is treated appropriately, there are circumstances when pharmacologic treatment of delirium is warranted. We recommend avoiding the use of antipsychotics when possible, as evidence syntheses suggest that their use does not decrease delirium duration or severity and many studies report an increased frequency of potentially harmful cardiac effects.Evidence 7Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Nikooie R, Neufeld KJ, Oh ES, et al. Antipsychotics for Treating Delirium in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1;171(7):485-495. doi: 10.7326/M19-1860. Epub 2019 Sep 3. PMID: 31476770. However, antipsychotic medications may be appropriate if a patient with delirium is causing imminent harm to self or others. Antipsychotic medications may also be appropriate if the patient is experiencing distressing hallucinations or delusions. Before considering the use of antipsychotics, we recommend the following:

1) Since delirium is a sign of underlying illness, it is not wise to conceal the symptoms of delirium by use of sedatives or antipsychotics without investigating the cause. Every attempt should be made to find and treat the underlying cause or causes.

2) From our experience, untreated or undertreated pain is a frequent contributor to delirium, particularly in postoperative or ICU patients. Patients with cognitive impairment or delirium may not reliably express pain, so a nonverbal pain assessment tool such as the PAINAD can be used to assess pain in these patients.

3) Be aware of the risk of antipsychotic use in patients with Parkinson disease. Dopamine antagonism will worsen stiffness and discomfort in this group. If an antipsychotic must be used, quetiapine at low doses is possibly the safest choice. Otherwise, low-dose trazodone or benzodiazepine may be considered. Although benzodiazepines may precipitate delirium, its use can be considered for sedation when antipsychotics are contraindicated in an agitated or violent patient.

4) Antipsychotics are a form of chemical sedation, and consent should be obtained before use when possible. Substitute decision-makers (SDMs) should be informed about the risks of untreated agitation as well as the risks of antipsychotic use. Ideally, electrocardiography (ECG) should be performed before starting antipsychotics to assess for QT prolongation. In general, giving low doses more frequently with monitoring is better than giving a single higher dose.

Antipsychotics and sedative-hypnotics that can be considered when indicated: Table 16.8-5.

PreventionTop

Delirium prevention is considered a standard of care in high-risk settings, such as medical/surgical wards, orthopedic wards, intensive care settings, and long-term care settings.

Nonpharmacologic Delirium Prevention

Multicomponent intervention: There is consistent evidence that a multicomponent nonpharmacologic intervention reduces the risk of delirium in both medical and surgical inpatient settings.Evidence 8Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity. Burton JK, Craig LE, Yong SQ, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Jul 19;7(7):CD013307. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013307.pub2. PMID: 34280303; PMCID: PMC8407051. Chen TJ, Traynor V, Wang AY, et al. Comparative effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for preventing delirium in critically ill adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022 Jul;131:104239. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104239. Epub 2022 Mar 28. PMID: 35468538. In several randomized controlled trials proactive geriatric medicine consultation or multidisciplinary geriatric surgical units can effectively reduce delirium incidence by addressing a wide range of predisposing and precipitating factors.

An alternative cost-effective solution is a multicomponent intervention delivered by volunteers. There are 6 key delirium prevention interventions derived from the Delirium Prevention Trial,Evidence 9Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999 Mar 4;340(9):669-76. PubMed PMID: 10053175. which resulted in the Hospital Elder Life Program (www.help.agscocare.org):

1) Ensure frequent reorientation of the patient.

2) Maintain adequate hydration.

3) Clean and put on eyeglasses for those with visual impairment.

4) Put on hearing aids or use personal amplifier for those with hearing impairment.

5) Ensure early and daily ambulation.

6) Provide nonpharmacologic sleep promotion, such as a warm drink (noncaffeinated), back rub, and a dark and quiet sleep environment.

Other interventions as part of a multicomponent approach include:

1) Avoidance of restraints/tethers, including belts, soft restraints, oxygen, IV catheters, and urinary catheters when possible.

2) Avoidance of medications at risk of causing or worsening delirium, such as anticholinergic and sedative medications.

3) Proactive treatment of pain and constipation.

4) Comprehensive geriatrics consultation.

We recommend a multicomponent intervention for delirium prevention in medical and surgical inpatients at moderate to high risk.Evidence 10Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity. Siddiqi N, Harrison JK, Clegg A, et al. Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Mar 11;3:CD005563. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005563.pub3. Review. PubMed PMID: 26967259. These interventions are simple and can be carried out by volunteers, nurses, allied health-care professionals, physicians, and even family members. We encourage hospital leadership to adopt this approach for all units caring for moderate-risk and high-risk patients (receiving pharmacotherapy, with hip fractures, from nursing homes, and in the ICU). Systematic implementation with continuous quality improvement is key in delirium prevention.

Despite testing multiple interventions, there is no convincing evidence of the benefit of any pharmacologic interventions for delirium prevention.

1. Antipsychotics: There have been a number of clinical trials testing the effectiveness of antipsychotic medications for delirium prevention in postoperative and ICU patients. Although several trials show a decreased incidence of delirium, there are significant concerns regarding adverse effects of antipsychotic medications and conversion to hypoactive delirium. Furthermore, antipsychotics do not prevent long-term complications of delirium. Overall, we do not recommend antipsychotic medications for delirium prevention.Evidence 11Weak recommendation (downsides likely outweigh benefits, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Oh ES, Needham DM, Nikooie R, et al. Antipsychotics for Preventing Delirium in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Oct 1;171(7):474-484. doi: 10.7326/M19-1859. Epub 2019 Sep 3. PMID: 31476766.

2. Cholinesterase inhibitors: We recommend against using cholinesterase inhibitors (eg, donepezil, rivastigmine) for prevention of delirium because clinical trials have not shown a benefit.Evidence 12Strong recommendation (downsides clearly outweigh benefits; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Siddiqi N, Harrison JK, Clegg A, et al. Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Mar 11;3:CD005563. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005563.pub3. Review. PubMed PMID: 26967259.

3. Melatonin: There is inconsistent evidence that melatonin or melatonergic drugs (eg, ramelteon) may decrease the incidence of delirium in postoperative or medical inpatients. However, the largest clinical trial to date did not demonstrate any benefits of melatonin.Evidence 13Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. de Jonghe A, van Munster BC, Goslings JC, et al; Amsterdam Delirium Study Group. Effect of melatonin on incidence of delirium among patients with hip fracture: a multicentre, double-blind randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014 Oct 7;186(14):E547-56. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140495. Epub 2014 Sep 2. PubMed PMID: 25183726; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4188685. There is insufficient evidence at this time to make a recommendation for melatonin for delirium prevention.

4. Gabapentin: We recommend against using gabapentin for prevention of postoperative delirium.Evidence 14Strong recommendation (downsides clearly outweigh benefits; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. Leung JM, Sands LP, Chen N, et al; Perioperative Medicine Research Group. Perioperative Gabapentin Does Not Reduce Postoperative Delirium in Older Surgical Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Anesthesiology. 2017 Oct;127(4):633-644. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001804. PubMed PMID: 28727581; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5605447. A single large randomized controlled trial showed no reduction in delirium incidence with postoperative gabapentin, but there was a signal toward increased harm in those undergoing hip surgery.

5. Peripheral nerve block: There is inconsistent evidence to support the use of peripheral nerve block in older adults with hip fractures for delirium prevention. A systematic review did not show a pooled benefit of delirium prevention when including adults with baseline cognitive impairment.Evidence 15Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity. Kim CH, Yang JY, Min CH, Shon HC, Kim JW, Lim EJ. The effect of regional nerve block on perioperative delirium in hip fracture surgery for the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2022 Feb;108(1):103151. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2021.103151. Epub 2021 Nov 23. PMID: 34826609.

6. Dexmedetomidine: There is inconsistent evidence to suggest the use of dexmedetomidine, a highly selective alpha-2 agonist, for delirium prevention in the ICU.Evidence 16Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to inconsistency and indirectness. Chen K, Lu Z, Xin YC, Cai Y, Chen Y, Pan SM. Alpha-2 agonists for long-term sedation during mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 6;1:CD010269. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010269.pub2. Review. PubMed PMID: 25879090; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6353054. Duan X, Coburn M, Rossaint R, Sanders RD, Waesberghe JV, Kowark A. Efficacy of perioperative dexmedetomidine on postoperative delirium: systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Anaesth. 2018 Aug;121(2):384-397. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.04.046. Epub 2018 Jun 22. PubMed PMID: 30032877.

7. Ketamine: We recommend against using ketamine for the prevention of postoperative delirium.Evidence 17Strong recommendation (downsides clearly outweigh benefits; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Avidan MS, Maybrier HR, Abdallah AB, et al; PODCAST Research Group. Intraoperative ketamine for prevention of postoperative delirium or pain after major surgery in older adults: an international, multicentre, double-blind, randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2017 Jul 15;390(10091):267-275. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31467-8. Epub 2017 May 30. Erratum in: Lancet. 2017 Jul 15;390(10091):230. PubMed PMID: 28576285; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5644286. A single large randomized controlled trial showed no reduction in delirium incidence but hallucinations and nightmares were significantly increased in the ketamine group.

8. Alternative strategies: Electroencephalography-guided anesthesia: Electroencephalography (EEG)-based monitors have been used in clinical practice to try to avoid postoperative delirium thought to be associated with excessive general anesthesia. Although some guidelines have recommended EEG-based monitoring for delirium prevention, there is limited and inconsistent evidence that EEG monitoring prevents postoperative delirium. There are ongoing large trials that will provide clarity to the utility of this intervention.Evidence 18Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, imprecision, and indirectness. Aldecoa C, Bettelli G, Bilotta F, et al. European Society of Anaesthesiology evidence-based and consensus-based guideline on postoperative delirium. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2017 Apr;34(4):192-214. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000594. Erratum in: Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018 Sep;35(9):718-719. PMID: 28187050. Sun Y, Ye F, Wang J, Ai P, Wei C, Wu A, Xie W. Electroencephalography-Guided Anesthetic Delivery for Preventing Postoperative Delirium in Adults: An Updated Meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2020 Sep;131(3):712-719. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004746. PMID: 32224720.

PrognosisTop

Delirium is a well-established predictor of poor prognosis. It is associated with increased length of hospital stay, risk of dementia, functional impairment, institutionalization, and death. There is evidence that a multicomponent nonpharmacologic intervention can improve short-term outcomes including length of stay and need for long-term care.Evidence 19Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity and indirectness. Hshieh TT, Yue J, Oh E, Puelle M, Dowal S, Travison T, Inouye SK. Effectiveness of multicomponent nonpharmacological delirium interventions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Apr;175(4):512-20. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7779. Erratum in: JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Apr;175(4):659. PubMed PMID: 25643002; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4388802. However, no study has shown improvement in long-term outcomes, even when delirium incidence was reduced.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Predisposing factors |

Precipitating factors |

|

– Advanced age – Neurodegenerative or cerebrovascular disease (eg, dementia, stroke) – History of delirium – History of alcohol abuse – Severe illness – Multimorbidity – Frailty and functional decline – Malnutrition – Vision and/or hearing impairment – Polypharmacy – Use of psychoactive medications – Uncontrolled pain |

– Any medical illness – Infection – Acute organ dysfunction (eg, cardiac, respiratory, renal, or hepatic failure) – Metabolic disturbance (eg, electrolyte abnormalities, endocrine disorders, hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia) – Alcohol and/or drug intoxication or withdrawal – Use of higher-risk medications associated with delirium (eg, psychoactive drugs, anticholinergics, opioids) – Dehydration and/or malnutrition – Iatrogenic events (eg, surgery) – Uncontrolled pain – Use of physical restraints – Use of indwelling bladder catheters – Immobilization |

|

D |

Drugs: Excess (eg, anticholinergics, sedative-hypnotics, opioids, corticosteroids, dopaminergics) and withdrawal (eg, alcohol, nicotine, benzodiazepines, antidepressants) |

|

E |

Electrical: Seizure, postictal |

|

L |

Low oxygen: Myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, pulmonary embolus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

|

I |

Infection: Urinary tract infection, pneumonia, cellulitis |

|

R |

Retention: Urine or stool |

|

I |

Intracranial: Trauma, subdural hematoma, tumor, malignancy, hemorrhage, stroke |

|

U |

Underhydration and undernutrition |

|

M |

Metabolic: Hyponatremia or hypernatremia, hypocalcemia or hypercalcemia, hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia, hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, uremia, liver failure, vitamin B12 deficiency, anemia |

|

Plus |

Pain |

|

Adapted with permission from the Saint Louis University Geriatrics Evaluation Mnemonics and Screening Tools, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, and the Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical, Saint Louis VA Medical Center. Available at slu.edu. | |

|

Drugs |

Examples |

|

Analgesics |

Opioids (especially meperidine [INN pethidine]) |

|

Anticholinergics |

– Tricyclic antidepressants (eg, amitriptyline, doxepin) – Antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine, dimenhydrinate, hydroxyzine) – Antimuscarinics (eg, scopolamine) – Incontinence agents (eg, oxybutynin) |

|

Anticonvulsants |

– Carbamazepine – Phenytoin – Valproic acid |

|

Sedative/hypnotics |

– Benzodiazepines (eg, triazolam, lorazepam, flurazepam, temazepam) – Barbiturates |

|

Muscle relaxants |

– Cyclobenzaprine – Baclofen |

|

Antipsychotics |

– Typical antipsychotics (eg, chlorpromazine) – Atypical antipsychotics (eg, olanzapine) |

|

Substance toxicity |

– Ethanol |

|

Glucocorticoids |

– Prednisone (in high doses) |

|

Antiparkinson agents |

– Pramipexole – Ropinirole – Amantadine – Levodopa |

|

Cardiac agents |

Digoxin |

|

Respiratory agents |

Theophylline |

|

Gastrointestinal agents |

– Metoclopramide – Loperamide |

|

Herbal preparations |

– Jimson weed – St John’s wort – Valerian – Kava kava |

|

This table should be used in context of each specific patient and one’s professional clinical judgment. In many clinical situations the drugs specified may be clinically appropriate and indicated. |

|

|

Etiology |

Investigations to consider |

Treatment suggestions |

|

Infections All settings: UTI, pneumonia, abdominal, cellulitis, skin ulcers, meningitis ICU: Venous catheter-associated infection, sepsis Surgical: Wound and surgical site infections |

Culture and image appropriately. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is common in older people and positive urine culture alone does not indicate UTI. Look for other causes of delirium |

Appropriate use of empiric antibiotics with adjustment based on culture and sensitivity |

|

Medication changes (new additions or withdrawal) |

Medication reconciliation, pill count |

Either taper/stop offending medications or treat medication withdrawal accordingly |

|

Alcohol withdrawal |

Alcohol level, anion gap, osmolar gap |

Treat with benzodiazepines, thiamine, and use CIWA to guide management |

|

Pain |

Pain scale, eg, PAINAD in those with cognitive impairment |

Appropriate pain management with acetaminophen and low-dose opioid medications (eg, hydromorphone). Consider peripheral nerve block or adjunct pain management strategies as appropriate |

|

Metabolic abnormality (eg, hypercalcemia, hyponatremia, hypernatremia) |

Blood test including sodium and calcium |

Determine cause and correct as indicated |

|

Urinary retention |

Bedside bladder US to determine PVR. Given the prevalence of urinary retention in the elderly, we typically check PVR in all cases of delirium. |

Urinary catheter for obstruction relief, UTI testing/treatment, urologic consultation if needed |

|

Constipation Surgical: Ileus |

Abdominal radiographs if indicated |

Treatment of constipation |

|

Hypoxia ICU: Ventilatory failure, ventilator-associated pneumonia |

Chest radiographs, arterial blood gas, ventilation settings |

Treat underlying cause (eg, COPD, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, aspiration) |

|

Serotonin syndrome |

Medication review |

Stop offending medications and treat with benzodiazepines |

|

Hepatic encephalopathy |

Ammonia level in appropriate situations |

Lactulose or polyethylene glycol, treatment underlying cause |

|

Uremic encephalopathy |

Creatinine and urea |

Consider dialysis |

|

Subdural hematoma, intracranial hemorrhage, stroke |

Neurologic deficits should prompt urgent CT or MRI of the head. Cardiac and vascular surgeries have particularly high risk for postoperative stroke |

Initiate ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke management. Neurosurgical consultation for CNS bleeding |

|

Postoperative complications |

Thorough history and physical exam looking for anastomotic leak, DVT, fluid overload, hematoma |

Treat causes |

|

Excess sedation (in ICU) |

Validated tools (eg, Richmond Agitation-Sedation scale) should be used to assess depth of sedation |

Avoid excess sedation |

|

Nonconvulsive status epilepticus |

In patients with persistent decreased level of consciousness not explained by structural cause EEG should be performed to exclude nonconvulsive status epilepticus |

Treatment of seizure with neurologic consultation |

|

Trauma |

Sometimes an unwitnessed fall leads to fracture or concussion that is manifested by delirium. Thorough physical examination is critical. Imaging of injured areas can be considered |

Treat as per injury |

|

CIWA, Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment; CNS, central nervous system; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT, computed tomography; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; EEG, electroencephalography; ICU, intensive care unit; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PVR, postvoid residual volume; US, ultrasonography; UTI, urinary tract infection. | ||

|

Psychotropics |

Dose |

Comments |

|

Haloperidol |

– Initial dose: 0.25 mg in frail older patients (0.5-1 mg in robust or younger patients) – May be given PO, SC, IM, or IV – May be given every 4 h, not exceeding 2 mg in a 24-h period in older patients |

– FDA “black-box warning” for risk of arrhythmia and death when dose is >10 mg in a 24-h period in patients of all ages – Parenteral route available – May cause QT prolongation |

|

Risperidone |

– Initial dose: 0.25 mg in frail older adults (0.5 mg in robust or younger patients) – May be given bid, not exceeding 2 mg in a 24-h period in older patients |

– PO only – May cause QT prolongation

|

|

Quetiapine |

– Initial dose: 6.25-12.5 mg in frail older patients (25 mg for robust or younger patients) – May be given bid |

– PO only – Increased risk of sedation – May cause QT prolongation – Least likely to cause extrapyramidal adverse effects. Can be considered in patients with Parkinson disease |

|

Lorazepam or other benzodiazepine |

– For lorazepam, initial dose 0.5 mg – May be given PO, SC, IM, or IV |

– Use for alcohol withdrawal – Consider in patients with Parkinson disease |

|

bid, 2 times a day; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; PO, oral; SC, subcutaneous. | ||

Figure 16.8-1. Framework for delirium risk.

Figure 16.8-2. Four scenarios illustrating interactions between vulnerability, stressor, and delirium risk. A line connecting the perceived vulnerability and stress levels determines the point of intersection on the delirium risk scale. Scenario A, an older adult that is fit, active, and independent with activities of daily living (low vulnerability) is prescribed a daily benzodiazepine for primary insomnia (mild stressor). The risk for developing delirium with short-term or long-term use of this high-risk drug is anticipated to be low. Scenario B, an older adult that is fit, active, and independent with activities of daily living (low vulnerability) is scheduled for coronary artery bypass grafting (severe stressor). The risk for developing postoperative delirium is anticipated to be intermediate. Scenario C, a frail 95-year-old adult with multimorbidity (high vulnerability) is scheduled for coronary artery bypass grafting (severe stressor). The risk for developing postoperative delirium is anticipated to be very high. Scenario D, an older adult with advanced dementia who is dependent for all activities of daily living (high vulnerability) is prescribed a daily benzodiazepine for primary insomnia (mild stressor). The risk for developing postoperative delirium is anticipated to be very high. Inspired by JAMA. 1996;275(11):852-7.

Figure 16.8-3. Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) delirium screening algorithm. Score based on cognitive testing. Adapted from Ann Intern Med. 1990; 113: 941-948 and Inouye SK. Confusion Assessment Method: Training Manual and Coding Guide. Available at www.help.agscocare.org (subscription required).