Canadian Adult Clinical Practice Guidelines. Obesity Canada. Accessed June 8, 2023. https://obesitycanada.ca/guidelines/chapters

Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, et al. 2022 American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO): Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2022 Dec;18(12):1345-1356. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2022.08.013. Epub 2022 Oct 21. PMID: 36280539.

Mechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S, et al. CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR THE PERIOPERATIVE NUTRITION, METABOLIC, AND NONSURGICAL SUPPORT OF PATIENTS UNDERGOING BARIATRIC PROCEDURES - 2019 UPDATE: COSPONSORED BY AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGISTS/AMERICAN COLLEGE OF ENDOCRINOLOGY, THE OBESITY SOCIETY, AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR METABOLIC & BARIATRIC SURGERY, OBESITY MEDICINE ASSOCIATION, AND AMERICAN SOCIETY OF ANESTHESIOLOGISTS - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY. Endocr Pract. 2019 Dec;25(12):1346-1359. doi: 10.4158/GL-2019-0406. Epub 2019 Nov 4. PMID: 31682518.

Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129(25 Suppl 2):S102-38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. Epub 2013 Nov 12. Erratum in: Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129(25 Suppl 2):S139-40. PMID: 24222017; PMCID: PMC5819889.

IntroductionTop

Excess weight has a profound effect on quality of life, metabolic disease states, mental health, and longevity (see Obesity: General Considerations). Weight loss may reverse those negative consequences and numerous weight-loss strategies are available, with varying degrees of short-term and, more importantly, long-term success. In this chapter we consider different surgical and nonsurgical procedures. Our data and judgements generally reflect North American and Canadian clinical practice guidelines.

New eligibility criteria for metabolic surgery (MS; nonexclusive list): The 2022 American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) guidelines recommend MS for patients with:

1) Body mass index (BMI) ≥35 kg/m2 regardless of the presence, absence, or severity of obesity-related conditions.

2) BMI ≥30 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidity.

3) BMI ≥27.5 mg/m2 in the Asian population.

These new recommendations replace the prior universally accepted 1991 National Institute of Health (NIH) Consensus Statement that patients with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or 35 kg/m2 and obesity-associated comorbid conditions are eligible for MS. An ideal surgical candidate is a highly motivated individual agreeable to long-term follow-up to achieve long-term success. Prior to surgery patients should undergo a rigorous and comprehensive assessment by a multidisciplinary team.

Ineligibility criteria (nonexclusive list):

1) Current drug or alcohol dependency.

2) Active or recent major cancer (life threatening, within the last 2 years).

3) Untreated or inadequately treated psychiatric illness.

4) Inability or unwillingness to commit to long-term follow-up.

5) Prohibitive high surgical risk.

Types of Surgeries and OutcomesTop

MS results in profound weight loss and significant improvement of comorbid conditions. Weight loss and improved metabolic parameters are the result of major physiologic changes that alter energy balance along with different degrees of malabsorption and restriction. These physiologic changes include changes in the level of gastrointestinal (GI) peptides, gut hormones, bile acids, and gut microbiota.

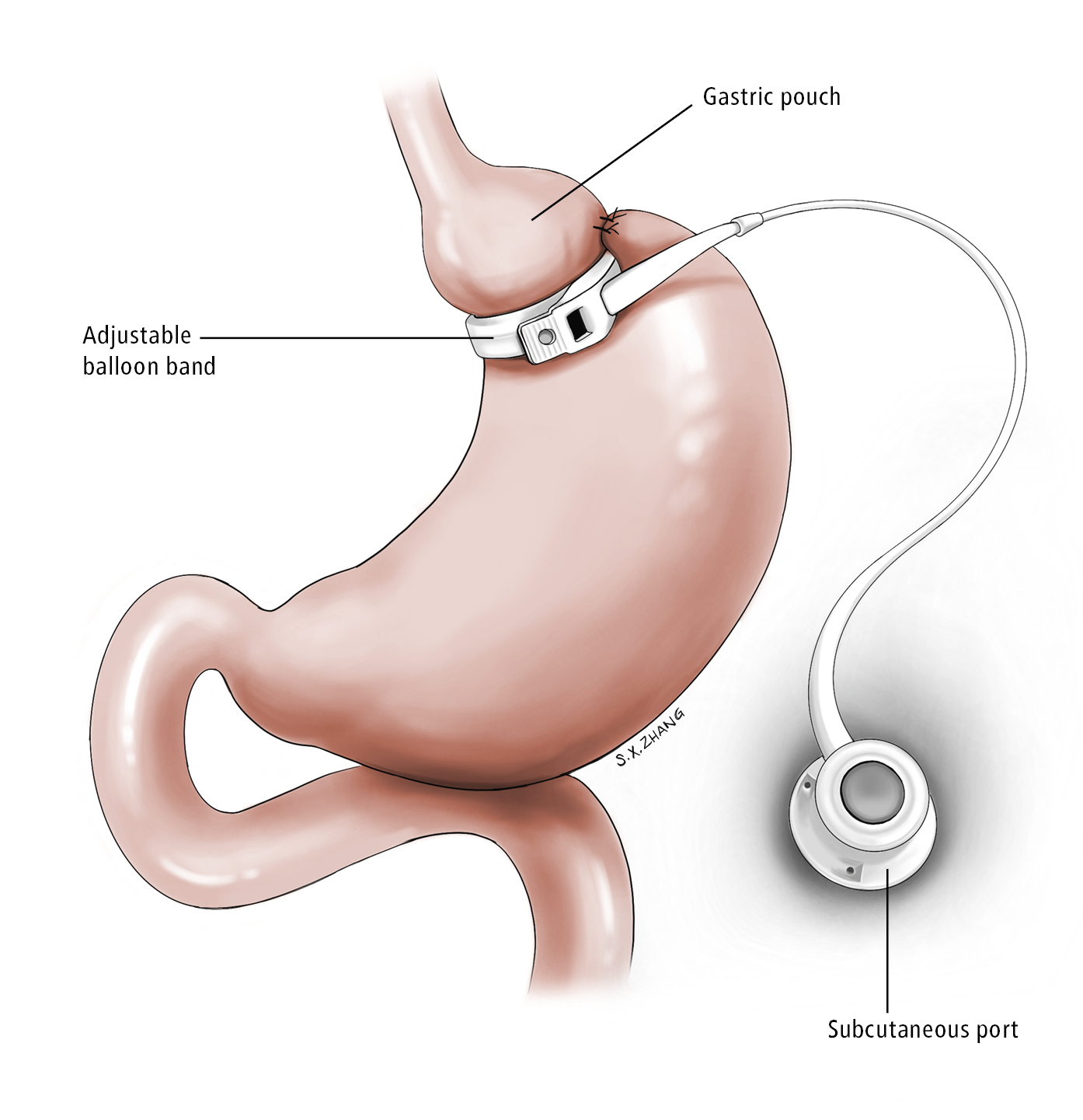

Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding (LAGB) is a restrictive and the least invasive bariatric procedure (Figure 6.5-1). An adjustable band is placed outside of the stomach so that it surrounds the upper portion of the stomach, allowing the creation of a small gastric pouch above the band. A port is placed within the abdominal wall and is connected to the band. The size of the opening between the upper gastric pouch and rest of the stomach can be adjusted by filling or removing normal saline through the abdominal port.

Weight loss is achieved by reducing the size of the stomach, which decreases hunger and, subsequently, caloric intake.

Expected beneficial effects and complications:

1) Up to 50% excess weight loss (EWL) at 1 year (or 7-10 BMI points).

| EWL = | current weight – ideal body weight (www.calculator.net) |

2) Reversible and adjustable.

3) Lower risk of micronutrient deficiencies compared with other bariatric procedures.

4) The procedure has fallen out of favor due to:

a) Only modest weight loss achieved.

b) Lack of sustained weight loss.

c) High rate of reoperation at 5 years due to complications.

d) Development of GI symptoms (dysphagia, vomiting, acid reflux) and food intolerances.

5) Early complications (≤30 days): Esophageal perforation, gastric perforation, or both.

6) Late complications (>30 days): Band erosion, migration, slippage, or all; gastric wall erosion; reflux and esophageal dilatation; mechanical issues with the band, tubing, or port.

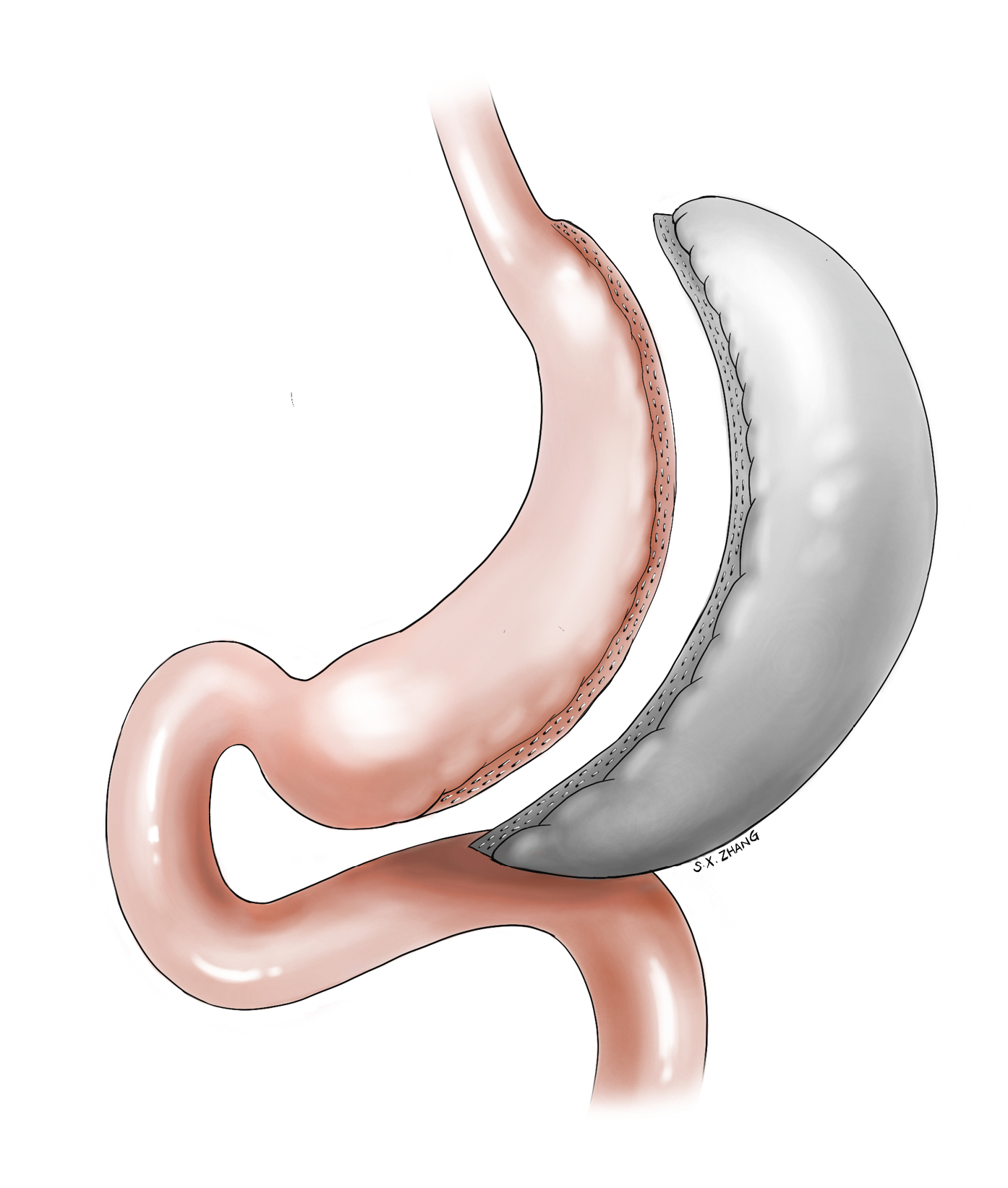

Vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) is also known as laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and is commonly called the “sleeve” (Figure 6.5-2). It is the most common bariatric surgery in the world and involves removing ~80% of the stomach in a vertical fashion, while a tubular sleeve or pouch remains. VSG is a technically easier surgery compared with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). It may be the surgery of choice based on patient preference, presence of adhesions making RYGB technically difficult, or medical conditions (eg, Crohn disease).

A relative contraindication to VSG is Barrett esophagus or severe GERD, which may worsen after surgery.

Weight loss is achieved by:

1) Changes in GI hormones, including decreases in ghrelin and increases in glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY) concentrations, which result in increased satiety and reduced hunger and appetite.

2) Reducing the size of the stomach, which decreases hunger and, subsequently, caloric intake.

Expected beneficial effects and complications:

1) Up to 50% to 70% EWL at 1 year (or 12-16 BMI points).

2) Irreversible.

3) Risk of micronutrient deficiencies, particularly vitamin B12, iron, calcium, and vitamin D, although lower than in the case of RYGB; required lifelong vitamin and mineral supplementation.

4) The possible weight loss is comparable with that in RYGB, although some studies have shown smaller weight loss.

5) Improvement or remission of type 2 diabetes is achieved in 40% of patients (a smaller percentage than with RYGB).

6) Can be performed as part of a staged procedure before biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS), or single-anastomosis duodenoileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S).

7) Complication rates put VSG between LAGB and RYGB.

8) Mortality at 30 days equals 0.1%.

9) Early complications (≤30 days): Leaks that can be difficult to manage, hemorrhage, stricture, intra-abdominal abscess, gastric fistula, incisional hernia.

10) Late complications (>30 days): GERD, chronic obstructive symptoms, dilatation of the gastric sleeve leading to weight regain.

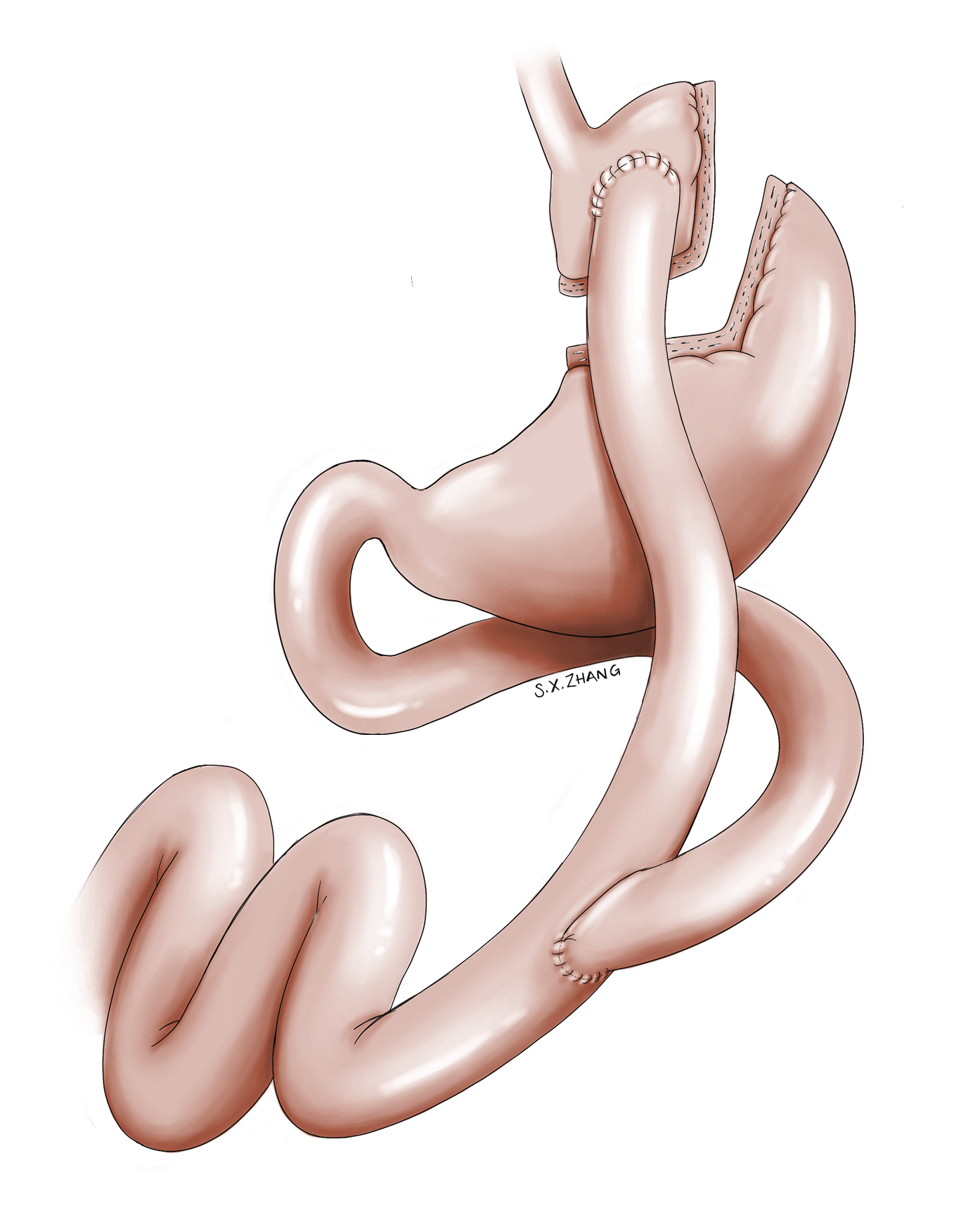

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is a surgery involving 2 components (Figure 6.5-3). First, the stomach is divided and a small pouch is created from the proximal stomach, occupying ~10% of the stomach volume. Second, the small intestine is divided usually about 50 to 150 cm from the ligament of Treitz. The distal small intestine, or Roux limb, is anastomosed to the stomach pouch, creating a gastrojejunostomy where a portion of the small intestine is bypassed. This limb carries food contents. The biliopancreatic limb, or Y limb (comprising distal stomach and proximal end of the small intestine), is connected to the Roux limb ~75 to 150 cm from the gastrojejunostomy. The Y limb carries digestive enzymes and bile. A relative contraindication to RYGB is Crohn disease.

Weight loss is achieved by:

1) Changes in GI hormones, including decreases in ghrelin and increases in GLP-1, PYY, and gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP) concentrations, resulting in increased satiety and reduced hunger and appetite.

2) Reducing the size of the stomach, which decreases hunger and, subsequently, caloric intake.

3) Bypassing the duodenum and proximal jejunum, which leads to malabsorption of various nutrients, resulting in further weight loss.

Expected beneficial effects and complications:

1) Expected ~65% to 70% EWL at 1 year (or 12-16 BMI points).

2) Potentially reversible.

3) Risk of micronutrient deficiencies, particularly vitamin B12, iron, calcium, vitamin D, folate, vitamin A, zinc, and copper; required lifelong vitamin and mineral supplementation.

4) RYGB may be more effective for weight loss compared with VSG.Evidence 1Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision. Peterli R, Wölnerhanssen BK, Peters T, et al. Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss in Patients With Morbid Obesity: The SM-BOSS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018 Jan 16;319(3):255-265. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20897. PMID: 29340679; PMCID: PMC5833546. Grönroos S, Helmiö M, Juuti A, et al. Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss and Quality of Life at 7 Years in Patients With Morbid Obesity: The SLEEVEPASS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2021 Feb 1;156(2):137-146. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5666. PMID: 33295955; PMCID: PMC7726698.

5) Improvement or remission of type 2 diabetes in 60% of patients.

6) Mortality at 30 days equals 0.2%, with higher complication rates than with VSG.

7) Early complications (≤30 days): Leaks (lower risk than for VSG), anastomotic stricture, hemorrhage, dumping syndrome.

8) Late complications (>30 days): Gastrogastric fistulas, marginal ulcers (high risk in smokers and chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), internal hernia, postprandial reactive hypoglycemia, kidney stones, gallstones, late dumping syndrome.

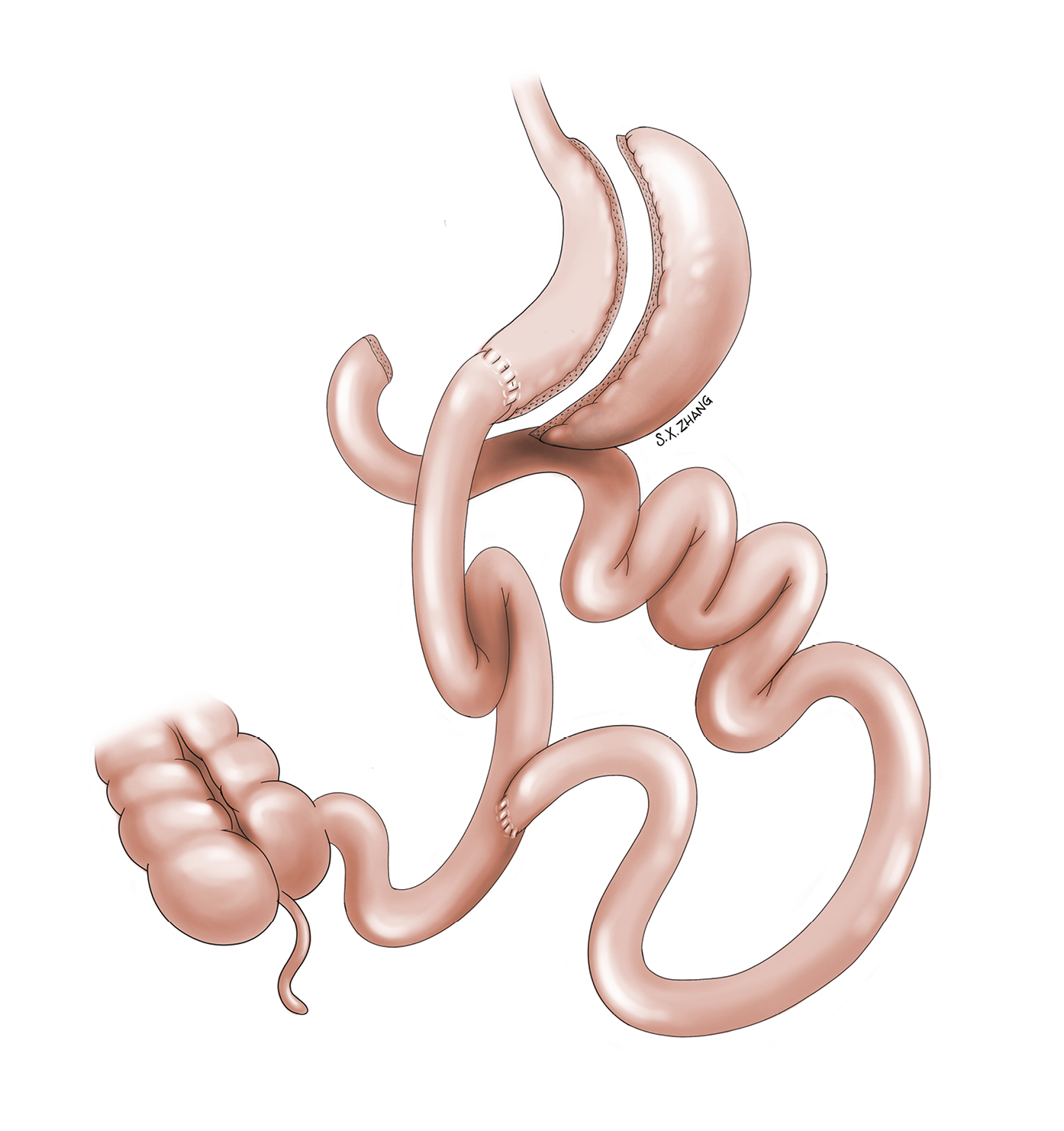

This procedure is associated with the greatest weight loss (Figure 6.5-4) and at the same time with the greatest risk of surgical complications and macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies due to the length of the small bowel that is bypassed. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS) is usually reserved for patients with higher BMIs or those who have undergone VSG or RYGB with weight regain. The surgery can be performed laparoscopically and has 2 components. In the first, a sleeve gastrectomy is performed that results in a tubular stomach pouch being created. The second component involves bypassing a large portion of the small intestine, leading to malabsorption. The duodenum is divided shortly after the pylorus and the ileum is divided ~250 cm proximally to the ileocecal valve. The distal end of the ileum is then anastomosed to the proximal end of the duodenum, creating the shorter common channel that carries food contents. About three-fourths of the small intestine is bypassed. An ileoileostomy is then performed by creating an anastomosis at the proximal end of the ileum, ~100 cm proximally to the ileocecal valve. This creates the longer limb, biliopancreatic loop, which carries digestive enzymes and bile to the distal small bowel. The length of the common channel is ~75 to 150 cm.

Weight loss is achieved by:

1) Reducing the size of the stomach, which decreases hunger and, subsequently, caloric intake.

2) Bypassing the duodenum, jejunum, and part of the ileum, leading to significant malabsorption of various nutrients, particularly protein and fat, which results in further weight loss.

3) Although BPD-DS is less studied than VSG or RYGB, it is thought that changes in GI hormones such as decreases in ghrelin and increases in GLP-1, PYY, and GIP concentrations play a role in increased satiety and reduced hunger and appetite.

Expected beneficial effects and complications:

1) Expected ~70% to 90% EWL by 2 years (or 16 BMI points).

2) Irreversible.

3) Risk of significant micronutrient deficiencies, particularly vitamin B12, iron, calcium, folate, zinc, copper, and all fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K); required lifelong vitamin and mineral supplementation.

4) Greater risk of protein malnutrition compared with VSG and RYGB.

5) The most effective surgery for weight loss compared with VSG and RYGB.

6) Improvement in insulin sensitivity, leading to the greatest improvement or remission of type 2 diabetes in >80% of patients.

7) Higher rates of complications compared with VSG and RYGB.

8) Early complications (≤30 days): Leaks, anastomotic stricture, hemorrhage, dumping syndrome.

9) Late complications (>30 days): Marginal ulcers (avoid NSAIDs after BPD-DS), small bowel obstruction, internal hernia, postprandial reactive hypoglycemia or late dumping syndrome, kidney stones, gallstones, higher rate of mortality.

Single-anastomosis duodenoileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) is a newer, modified version of the BPD-DS surgery. It is less invasive and complex, as it only requires 1 anastomosis. However, it is still considered experimental. The proximal portion of the divided duodenum is anastomosed to a distal portion of the ileum, creating a loop duodenoileostomy. The length of the common channel is usually ~300 cm.

Expected beneficial effects and complications:

1) Expected ~70% to 90% EWL by 2 years (or 16 BMI points).

2) Irreversible.

3) Risk of significant micronutrient deficiencies, particularly vitamin B12, iron, calcium, folate, zinc, copper, and all fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K); required lifelong vitamin and mineral supplementation.

4) Greater risk of protein malnutrition.

5) May result in a longer hospital stay compared with other bariatric surgeries.

6) Fewer complications compared with BPD-DS, including lower risk of diarrhea, dumping syndrome, and vitamin or mineral deficiencies due to increased length of the common channel and only 1 anastomosis.

7) Lower risk for small bowel obstruction, internal hernias, and leaks, as there is 1 anastomosis.

8) The studies are limited, but weight loss outcomes appear similar to those achieved with DS and RYGB.

Multiple studies have shown that bariatric surgeries, also known as metabolic or weight loss surgeries, are superior to previous medical treatment in achieving sustained weight loss in the long term.Evidence 2High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Aug 8;(8):CD003641. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003641.pub4. PMID: 25105982. Bariatric surgeries are more efficacious than lifestyle interventions with pharmacologic treatment and result in greater improvement or resolution of diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, sleep apnea, and fatty liver disease.Evidence 3Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to observational nature of most studies and increased due to strength of association. Wiggins T, Guidozzi N, Welbourn R, Ahmed AR, Markar SR. Association of bariatric surgery with all-cause mortality and incidence of obesity-related disease at a population level: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020 Jul 28;17(7):e1003206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003206. PMID: 32722673; PMCID: PMC7386646. Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Aug 8;(8):CD003641. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003641.pub4. PMID: 25105982. MS is also associated with reduced long-term all-cause mortality in patients with obesity (30%-40%) when compared with matched individuals with obesity.Evidence 4Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to observational nature of studies and risk of bias. Wiggins T, Guidozzi N, Welbourn R, Ahmed AR, Markar SR. Association of bariatric surgery with all-cause mortality and incidence of obesity-related disease at a population level: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020 Jul 28;17(7):e1003206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003206. PMID: 32722673; PMCID: PMC7386646. They may also be associated with up to 40% reduction in incidence of certain cancers such as endometrial, breast, and prostate cancer,Evidence 5Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to observational nature of studies. Wolin KY, Carson K, Colditz GA. Obesity and cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15(6):556-65. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0285. Epub 2010 May 27. PMID: 20507889; PMCID: PMC3227989. but likely not colorectal cancer.Evidence 6Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to observational nature of studies. Wolin KY, Carson K, Colditz GA. Obesity and cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15(6):556-65. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0285. Epub 2010 May 27. PMID: 20507889; PMCID: PMC3227989. Significant weight loss after surgery positively affects patients’ lives. A significant number of patients experience improvement in quality of life, sex life, body self-image, depressive symptoms, and anxiety. However, post surgery patients may also experience worsening mental health with increased risk of eating disorders, alcohol/substance use, and suicide risk (the hazard ratio is 2.4 times higher than in nonsurgical controls). Thus, it is crucial that patients are carefully screened and educated preoperatively and receive close postoperative follow-up.Evidence 7Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to observational nature of studies.Adams TD, Meeks H, Fraser A, et al. Long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality for four bariatric surgery procedures. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2023 Feb;31(2):574-585. doi: 10.1002/oby.23646. PMID: 36695060; PMCID: PMC9881843.

In summary, bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for obesity and the only intervention that has been demonstrated to result in significant and sustained weight loss in the long term. Concurrent lifestyle interventions are the mainstay for any successful weight loss intervention and foundation for success of bariatric surgery.

With improved surgical and laparoscopic techniques, bariatric surgery is safe. It is associated with a 30-day mortality rate of 0.1% to 0.2% (which is similar to that of laparoscopic cholecystectomy) and a surgical complication rate <3%. MS significantly improves obesity-related comorbidities, including diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, fatty liver disease, and obstructive sleep apnea, as well as quality of life.

Typically, a patient can expect to lose 20% to 40% of their total presurgery weight, depending on the type of the surgical procedure done.

It is important to understand that, similar to lifestyle interventions and medications, the response to MS is variable and some weight regain can be expected over time. There is no one surgery that would be the best for all patients, but there is a best surgical procedure for each individual patient. The choice of surgery depends on the patient’s medical history and should be based on a shared decision-making process that includes the patient’s risks, goals, values, and preferences.

Comparison of outcomes of different types of MS: Table 6.5-1.

Postoperative Care and Follow-UpTop

Lifelong follow-up is key to long-term success after MS. Most bariatric centers follow patients for the first 1 to 2 years; after that the follow-up is ensured by their usual care providers.

Following surgery patients are encouraged to eat ≥3 structured meals per day and 2 snacks. Patients should maintain a daily protein intake of 60 to 120 g, depending on the bariatric surgery that has been performed. To avoid food intolerances patients are advised to eat slowly and chew the food thoroughly. Simultaneous eating and drinking is not recommended; fluids should be avoided during meals.

Health-care providers should review the patient’s weight, adherence to healthy eating habits, protein intake, activity level, adherence to vitamin and mineral supplementation, and psychologic well-being at least yearly. Screening for the development and/or relapse of comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), osteoarthritis (OA), and dyslipidemia should also be done yearly.

Smoking status should be evaluated regularly and smoking cessation should be encouraged, as smoking post MS is associated with marginal ulcerations that are difficult to treat. Regular physical activity and routine exercising should be encouraged.

In general, following MS patients are recommended to take a daily multivitamin (preferably a bariatric-specific one), calcium in the form of calcium citrate, vitamin D, vitamin B12, and iron supplement (in menstruating women). Patients who underwent highly malabsorptive procedures, such as the duodenal switch, require supplementation of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K).

Regular monitoring of signs and symptoms of nutritional deficiencies and laboratory testing at regular intervals (every 3-6 months for the first year and yearly thereafter) are recommended.

Bone density assessment with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) should be performed 2 years following malabsorptive procedures.

Patients should be advised to avoid NSAIDs following bariatric surgery due to the risk of marginal ulcerations. Women in fertile years should receive contraceptive counseling, as oral contraceptives might not be effective after malabsorptive procedures. Pregnancy should be avoided for 12 to 18 months after surgery and, ideally, should be planned. Women who become pregnant after MS may have reduced risk of gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, Cesarean section, and large-for-gestational age infants. However, they may be at an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age infants. There is no change in the risk for congenital malformations.

Weight Recidivism After Bariatric Surgery

It is expected to see some weight regain after MS, which can be attributed to adaptative intestinal changes, changes in lifestyle such as dietary nonadherence, and decreased physical activity. No universal consensus has been established for excessive weight regain after bariatric surgery. Some consider that a >25% regain of the total weight lost may occur in about one-third of all patients. Weight regain is most commonly multifactorial and can be attributed to a combination of dietary nonadherence, lack of physical activity, mental health issues, endocrine and metabolic conditions, or a combination of these. Rarely weight regain is due to failure of the surgical procedure. The approach to weight regain should include comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s dietary habits, activity level, and psychologic status to identify and address mental health conditions such as mood disorders, eating disorders, and unhealthy behaviors. Once all potential causes have been addressed, consideration can be given to the use of antiobesity medications and re-referring the patient to a surgeon for consideration of a revision or conversion surgery.

Nonsurgical Weight Loss ProceduresTop

A number of nonsurgical weight loss procedures have emerged over time. They can be considered for patients who may choose not to undergo a surgical procedure or do not qualify for surgery based on medical-surgical assessment. The effectiveness and complication rates of nonsurgical weight loss procedures are between those for medical and surgical treatments, but the long-term data on complication rates and weight loss outcomes are still insufficient. Many of these procedures are used as temporary solutions.

1. Intragastric balloons: A gastric balloon is inserted endoscopically into the stomach under sedation or general anesthesia. The weight loss results from increased sense of satiety and delayed gastric emptying. It is a short-term temporary strategy; retrieval of the balloon has to be done at 6 months to minimize long term complications. Removal of the balloon results in weight regain. The procedure is generally performed for a BMI between 30 and 40 kg/m2. Specific contraindications to balloon therapy include, but are not limited to, prior gastric surgery, potential bleeding lesion of the GI tract, and a hiatus hernia ≥5cm. Long-term follow-up is essential. Common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, and abdominal pain. Serious complications have been reported including bowel obstruction, gastric ulceration with perforation, and death. The EWL equals 25% to 40%. Balloon therapies approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are endorsed by the ASMBS/Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES).

2. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty: The primary obesity surgery endoluminal (POSE) procedure reduces the size of the stomach by endoscopic placing of sutures to create folds in the gastric body. Following a meal the stomach cannot expand, which gives patients a sense of fullness. The procedure tries to mimic sleeve gastrectomy. Patients lose weight through caloric restriction. An indication for the procedure is a BMI of 30 to 35 kg/m2. The expected EWL is 40%. This procedure is not endorsed by the ASMBS.

3. Vagal blockade: A laparoscopically inserted device (electric pulse generator) is placed subcutaneously and connected to the 2 wires implanted on the vagal nerve. The device is activated for 12 to 15 hours. It is presumed that electric stimulation blocks the vagal nerve conduction, which reduces the signal of hunger communicated to the brain. The procedure has been approved by the FDA but is not endorsed by the ASMBS. The EWL is reported at 21% (8% total body weight loss [TBWL]). Common adverse events include pain at site of the implant, heartburn, and dyspepsia.

Duodenal-jejunal endoscopic bypass (EndoBarrier): A linear 60-cm-long plastic sleeve is placed endoscopically under sedation in the first part of the duodenum for ≤12 months. The liner prevents food contact with bile and transports undigested food to the proximal jejunum. It has similar effects as the RYGB. The procedure-associated complications include abdominal discomfort and nausea. More serious complications, like device migration, bowel obstruction, or liver abscess, are also possible. The EWL is 12% to 32%. EndoBarrier is not approved for use in the United States or Europe yet.

Tables AND FIGURESTop

|

Procedure |

Gastric band |

Sleeve gastrectomy |

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass |

Duodenal switch/BPD |

|

TBWL |

10%-15% |

20%-25% |

30%-35% |

40% |

|

EWL |

40%-50% |

50%-70% |

65%-70% |

70%-90% |

|

BMI change |

7-10 points |

12-16 points |

12-16 points |

>16 points |

|

Improvement or resolution of diabetes |

45% |

80% |

80% |

99% |

|

Improvement or resolution of hypertension |

20% |

30% |

40% |

60% |

|

Improvement or resolution of dyslipidemia |

Significant reduction in TC, LDL-C, TG and significant increase in HDL-C. Greater benefit following duodenal switch and gastric bypass |

|||

|

Improvement or resolution of OSA |

Conflicting results. Overall significant reduction in apnea-hypopnea index and Epworth sleepiness scale score |

|||

|

30-day mortality rate |

0.01% |

0.1% |

0.2% |

0.2%-0.6% |

|

BMI, body mass index; BPD, biliopancreatic diversion; EWL, excess weight loss; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; TBWL, total body weight loss; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides. |

||||

Figure 6.5-1. Gastric band. Illustration courtesy of Dr Shannon Zhang.

Figure 6.5-2. Sleeve gastrectomy. Illustration courtesy of Dr Shannon Zhang.

Figure 6.5-3. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Illustration courtesy of Dr Shannon Zhang.

Figure 6.5-4. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Illustration courtesy of Dr Shannon Zhang.