Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Etrasimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (ELEVATE): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies. Lancet. 2023 Apr 8;401(10383):1159-1171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00061-2. Epub 2023 Mar 2. Erratum in: Lancet. 2023 Mar 25;401(10381):1000. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00586-X. PMID: 36871574.

Danese S, Vermeire S, Zhou W, et al. Upadacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from three phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, randomised trials. Lancet. 2022 Jun 4;399(10341):2113-2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00581-5. Epub 2022 May 26. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Sep 24;400(10357):996. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01069-8. PMID: 35644166.

Spinelli A, Bonovas S, Burisch J, et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Surgical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Feb 23;16(2):179-189. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab177. PMID: 34635910.

Raine T, Bonovas S, Burisch J, et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Medical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Jan 28;16(1):2-17. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab178. PMID: 34635919.

Benchimol EI, Tse F, Carroll MW, et al. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology clinical practice guideline for immunizations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (Part 2): inactivated vaccines. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2021 Jul 29;4(4):e59-e71. doi: 10.1093/jcag/gwab015. PMID: 34476338; PMCID: PMC8407487.

Jones JL, Tse F, Carroll MW, et al. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology clinical practice guideline for immunizations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (Part 2): inactivated vaccines. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2021 Jul 29;4 (4):e72-e91. doi: 10.1093/jcag/gwab016. eCollection 2021 Aug. PMID: 34476339; PMCID: PMC8407486.

Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, et al; AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr;158(5):1450-1461. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.006. Epub 2020 Jan 13. PMID: 31945371.

Ko CW, Singh S, Feuerstein JD, et al; American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2019 Feb;156(3):748-764. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.009. Epub 2018 Dec 18. PMID: 30576644.

Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, et al; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017 Jun 1;11(6):649-670. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx008. PMID: 28158501.

Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al; OCTAVE Induction 1, OCTAVE Induction 2, and OCTAVE Sustain Investigators. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017 May 4;376(18):1723-1736. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606910. PMID: 28467869.

Bressler B, Marshall JK, Bernstein CN, et al; Toronto Ulcerative Colitis Consensus Group. Clinical practice guidelines for the medical management of non-hospitalized ulcerative colitis: the Toronto consensus. Gastroenterology. 2015 May;148(5):1035-1058.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.001. Epub 2015 Mar 4. Review. PMID: 25747596.

Walsh AJ, Ghosh A, Brain AO, et al. Comparing disease activity indices in ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2014 Apr;8(4):318-25. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.010. Epub 2013 Oct 10. PMID: 24120021.

Nguyen GC, Bernstein CN, Bitton A, et al. Consensus statements on the risk, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in inflammatory bowel disease: Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2014 Mar;146(3):835-848.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.042. Epub 2014 Jan 22. Review. PMID: 24462530.

Bitton A, Buie D, Enns R, et al; Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Severe Ulcerative Colitis Consensus Group. Treatment of hospitalized adult patients with severe ulcerative colitis: Toronto consensus statements. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Feb;107(2):179-94; author reply 195. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.386. Epub 2011 Nov 22. PMID: 22108451. 23040453.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a diffuse inflammatory condition involving the rectum and extending proximally to a varying degree. UC and Crohn disease (CD) are the 2 major forms of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). The etiology of IBD remains uncertain but centers on an overactive intestinal immune response in individuals with a genetic predisposition.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

1. Signs and symptoms: The most common presenting symptoms are increased stool frequency, rectal bleeding, and urgency. In patients with limited proctitis stool frequency may be normal and even constipation may occur. In such cases rectal bleeding may be the only symptom. Fatigue and weight loss are frequent. Severe flares may be associated with symptoms of dehydration, tachycardia, abdominal tenderness, and fever. Signs and symptoms of specific intestinal and extraintestinal manifestations of IBD are described below.

2. Clinical classification: Inflammatory lesions may be confined to the rectum (proctitis) or extend proximally and contiguously through the colon. In some cases of pancolitis, “backwash” ileitis can also occur. Patients with distal disease can have localized periappendiceal inflammation, referred to as a cecal patch. The following classification of disease extent can have practical implications for the choice of treatment modality (topical vs systemic):

1) Proctitis, with inflammation limited to the rectum.

2) Left-sided colitis, with inflammation above the rectum but distal to the splenic flexure.

3) Extensive colitis, with inflammation proximal to the splenic flexure (but not limited to the cecal patch).

3. Natural history: UC is a chronic condition with periods of active disease (“flares”) and periods of remission. Most flares are unexplained, but some are associated with specific triggers, such as stress, changes in diet, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), enteric infections, and antibiotic therapy.

4. Classification of disease activity: A variety of scoring systems have been developed to grade the activity of UC. The most commonly used of these is the Mayo score (Table 7.2-1), which combines symptoms with endoscopic findings and physician global assessment (PGA). The score ranges from 0 to 12 points, with higher scores indicating more severe disease. The STRIDE (Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease) consensus advocated eliminating the PGA to leave 2 patient-reported outcomes (stool frequency and bleeding) and endoscopy. Symptoms may not be an accurate measure of disease activity and therefore the use of objective measures (eg, serum C-reactive protein [CRP] levels, fecal calprotectin levels, endoscopy) is encouraged.

DiagnosisTop

1. Laboratory tests: No abnormalities are specific for UC. In patients with active disease the following may be observed:

1) Features of inflammation: Elevated serum C-reactive protein (CRP), thrombocytosis, leukocytosis.

2) Anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and electrolyte disturbances (in severe disease).

3) Elevated fecal calprotectin levels.

4) Negative testing for infectious gastroenteritis. Patients with active disease should also be tested specifically for Clostridioides difficile infection.

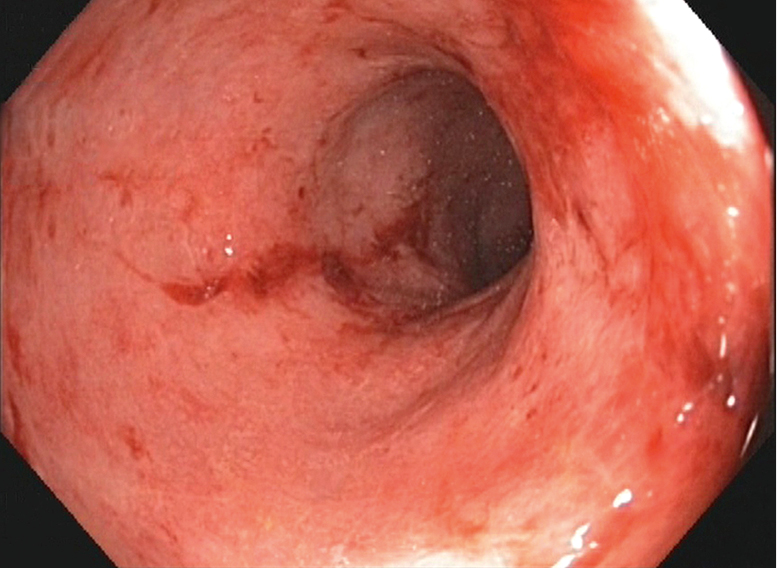

2. Endoscopy (Figure 7.2-18) can be performed without prior preparation on the first presentation (cathartics such as phosphate enemas may change the endoscopic appearance). Biopsy is important to confirm diagnosis. In active disease the mucosa is erythematous, granular, edematous, and friable; contact bleeding is observed and the vascular pattern is absent. In severe forms, ulcers, pseudopolyps, purulent exudate, and blood are seen in the intestinal lumen. In periods of remission the appearance of the mucosa may be normal. Use standardized scoring systems for endoscopic assessment of disease activity (eg, Mayo Endoscopic Subscore [Table 7.2-1], Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity). Full colonoscopy is not needed for diagnosis and may be contraindicated in more active disease. However, colonoscopy is useful to define disease extent, differentiate UC from CD, and survey for cancer.

3. Imaging studies:

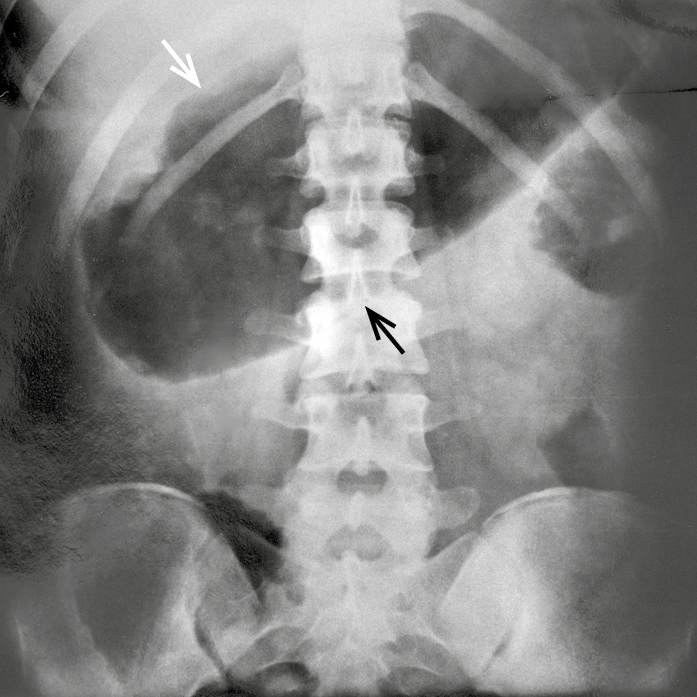

1) Plain abdominal radiographs may reveal thumbprinting, signifying mucosal edema. Colonic dilation in patients with active disease (transverse colon >6 cm in diameter in the median plane: Figure 7.2-19) is a concerning finding suggestive of toxic megacolon.

2) Barium enema in early disease shows mucosal granularity and shallow mucosal ulceration. Chronic inflammation can lead to inflammatory polyps, loss of haustration, and shortening of the colon (lead-pipe appearance). Barium enema is now performed rarely and should be avoided in severe disease.

3) Cross-sectional imaging with ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can show mural thickening with stratification, loss of haustration, and widening of the presacral space. CT is not sensitive for mild mucosal disease. In severe disease CT is useful to exclude perforation and abscess.

4. Histologic features depend on the phase of the disease. In active disease increased numbers of granulocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells are present in the lamina propria, along with crypt abscesses and reduced numbers of goblet cells. In remission distorted glandular architecture, thinning of muscularis mucosa, and Paneth cell metaplasia are observed. Standardized scoring systems for the assessment of histologic disease activity have been developed, but they have not been widely adopted yet (eg, Geboes score, Robarts Histopathology Index, Nancy Index). Examination for features of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is important in patients with severe disease activity.

Diagnosis is based primarily on endoscopic and histologic findings.

Differential diagnosis includes bacterial (eg, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, gonococci) or parasitic (eg, amebiasis) infection, pseudomembranous colitis, CD (Table 7.2-2), colorectal cancer, ischemic colitis, and radiation proctitis.

TreatmentTop

1. Classes of medications:

1) Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) compounds, administered as pure 5-ASA (mesalazine) or its derivatives: sulfasalazine, olsalazine, and balsalazide. Mesalazine can also be administered rectally as suppositories or enemas (either foam or liquid).

2) Oral glucocorticoids include prednisone, prednisolone, and budesonide. IV glucocorticoids include hydrocortisone and methylprednisolone.

3) Immunosuppressants include thiopurines (azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine) and cyclosporine (INN ciclosporin).

4) Biologic agents include tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha antagonists (adalimumab, golimumab, infliximab), the alpha4beta7 leukocyte integrin antagonist vedolizumab, the interleukin (IL) 12/23 antagonist ustekinumab, and the IL- 23 antagonists mirikizumab and risankizumab.

5) The Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors tofacitinib and upadacitinib.

6) The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (S1PR) modulators ozanimod and etrasimod.

2. Both 5-ASA and glucocorticoids (hydrocortisone, budesonide) can be administered rectally as suppositories or enemas, as monotherapy in patients with distal disease, or as adjuncts to systemic therapies in patients with more extensive disease.

Treatment of Active Disease (Induction of Remission)

Mild to Moderate Disease Activity

1. Outpatient management is typical. In general, there is no restriction of lifestyle and diet. Strategies to maintain and follow bone health should be discussed (prevention and treatment of bone mineral loss: see Osteoporosis). Vaccinations should be updated, recognizing that live vaccines cannot be administered in patients receiving immunosuppressants or biologic therapy.

2. Selection of drugs:

1) Proctitis: 5-ASA suppositories (or enemas) ≥1 g/d as monotherapy or in combination with oral 5-ASA or rectal glucocorticoid.

2) Left-sided colitis: 5-ASA enemas Evidence 1Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Marshall JK, Thabane M, Steinhart AH, Newman JR, Anand A, Irvine EJ. Rectal 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Jan 20;(1):CD004115. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004115.pub2. Review. PMID: 20091560. combined with oral 5-ASA >2 g/d. Oral 5-ASA monotherapy and rectal 5-ASA or glucocorticoid monotherapy can be considered but are less effective.

3) Extensive colitis: Oral 5-ASA >2 g/d as monotherapy or preferably in combination with rectal 5-ASA.

4) Consider oral systemic glucocorticoids if 5-ASA therapy is optimized and fails, or in patients with a significant disease activity. Oral budesonide formulations with colonic delivery can also be used in mild to moderate disease in patients who do not respond to or do not tolerate 5-ASA.

1. Hospitalization is usually required. Perform tests for C difficile and CMV and sigmoidoscopy without preparation to take biopsies to confirm the diagnosis and exclude CMV infection, as well as plain abdominal radiography to identify possible complications that require urgent surgical assessment (toxic megacolon or perforation). Prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism (VTE) should be administered (see Primary Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism).Evidence 2Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the observational nature of studies. Support for this recommendation is inferred from benefit of intervention in unselected nonsurgical hospitalized patients. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(2 Suppl):e195S-226S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2296. PMID: 22315261; PMCID: PMC3278052.

2. Intensive medical management:

1) Administer IV hydration. Oral or enteral feeding is preferred, but patients unable to tolerate enteric feeds or those who require surgery should be considered for parenteral nutrition.

2) Initiate IV glucocorticoids with hydrocortisone 300 mg/d or methylprednisolone 60 mg/d (in the case of glucocorticoid intolerance use infliximab or IV cyclosporine). Evaluate the response to glucocorticoids (stool frequency, CRP, plain abdominal radiography) after 3 days. If effective, continue the glucocorticoid for an additional 4 to 7 days before switching to oral therapy and taper down the dose. Otherwise consider surgery or second-line therapy.

3) Second-line therapy is IV infliximab 5 to 10 mg/kg or IV cyclosporine 2 mg/kg/d. Tofacitinib or upadacitinib can be considered as an alternative in patients already exposed to a TNF antagonist. If there is no improvement within 5 to 7 days (or earlier in case of deterioration), consider surgery (colectomy).

4) Do not use antibiotics unless there is evidence of bacterial infection.

3. Manage specific complications (see Complications, below).

Relapses and Refractory Disease

1. For patients who relapse despite treatment with 5-ASA, consider 5-ASA dose optimization, concomitant oral/rectal 5-ASA, or oral glucocorticoids.

2. For patients with glucocorticoid-refractory disease, consider biologic therapy Evidence 3Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr;106(4):644-59, quiz 660. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.73. Epub 2011 Mar 15. Review. PMID: 21407183. Lawson MM, Thomas AG, Akobeng AK. Tumour necrosis factor alpha blocking agents for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Jul 19;(3):CD005112. Review. PubMed PMID: 16856078. Lv R, Qiao W, Wu Z, Wang Y, Dai S, Liu Q, Zheng X. Tumor necrosis factor alpha blocking agents as treatment for ulcerative colitis intolerant or refractory to conventional medical therapy: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014 Jan 27;9(1):e86692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086692. eCollection 2014. PMID: 24475168; PMCID: PMC3903567. (alone or in combination with an immunosuppressant), a JAK inhibitor, or S1PR modulator.

3. For patients with glucocorticoid-dependent disease, consider a thiopurine, biologic therapy (alone or in combination with an immunosuppressant), a JAK inhibitor, or an S1PR modulator.

4. Always consider surgery.

Long-term maintenance therapy to prevent relapse should be considered in all patients with UC after successful induction. The choice of agent depends on the extent, frequency, and severity of the disease, effectiveness of previous maintenance therapy, and drug used during previous exacerbations.

1. For patients responding to oral or rectal 5-ASA or to glucocorticoids, the maintenance treatment of choice is oral or rectal 5-ASA. Once-daily dosing of oral 5-ASA ≥2 g/d is acceptable.Evidence 4Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to concerns about the single-blind design of some trials, and concern that the adherence in clinical trials may not reflect the adherence in community settings. Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Oct 17;10:CD000544. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000544.pub3. Review. PMID: 23076890. Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Once daily oral mesalamine compared to conventional dosing for induction and maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012 Sep;18(9):1785-94. doi: 10.1002/ibd.23024. Epub 2012 May 29. Review. PMID: 22644954. Ford AC, Khan KJ, Sandborn WJ, Kane SV, Moayyedi P. Once-daily dosing vs. conventional dosing schedule of mesalamine and relapse of quiescent ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Dec;106(12):2070-7; quiz 2078. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.296. Epub 2011 Sep 6. Review. PMID: 21894226. Rectal 5-ASA can be administered daily or titrated to a reduced dose frequency (eg, 3 d/wk). Use rectal treatments in patients with proctitis, oral or rectal treatments in patients with left-sided colitis, and oral treatments in other patients. Apart from maintaining remission, a potential benefit of 5-ASA maintenance therapy is chemoprevention of colorectal cancer. Second-line treatment is a long-term combination of oral and rectal 5-ASA.

2. For patients who require repeated courses of glucocorticoids, consider a thiopurine, biologic agent (either alone or in combination with a thiopurine), JAK inhibitor, or S1PR modulator.

3. For patients in whom remission was induced with an anti-TNF agent, continue that agent alone or in combination with a thiopurine.

4. For patients in whom remission was induced with an anti-integrin agent, continue that agent.

5. For patients in whom remission was induced with an anti-IL-12/23 or anti-IL 23 agent, continue that agent.

6. For patients in whom remission was induced with a JAK inhibitor or S1PR modulator, continue that agent as maintenance therapy.

1. Indications for surgical treatment include persistent UC symptoms despite optimal medical treatment. In severe UC not responding to intensive glucocorticoid treatment within 3 to 5 days or within 5 to 7 days of rescue therapy with infliximab or cyclosporine, surgical treatment is urgent. Other indications include cancer or dysplasia, colonic stricture, or (rarely) refractory extraintestinal manifestations.

2. Types of surgery:

1) Total resection of the rectum and colon (proctocolectomy) with formation of a permanent end ileostomy.

2) Restorative proctocolectomy with formation of an ileal pouch and an ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA). This avoids a permanent stoma but may require up to 3 stages for completion, including temporary ileostomy.

Follow-UpTop

1. Objective measures of disease activity (complete blood count [CBC], CRP, fecal calprotectin) every 3 to 12 months. Colonoscopy at 3 to 6 months after starting induction therapy and then every 1 to 5 years.

2. Monitoring for hepatobiliary complications (clinical assessment, liver biochemistry testing) every 12 months.

3. Cancer surveillance (colonoscopy recommended in various clinical practice guidelines and repeated at intervals depending on previous findings and disease duration). As a minimum, surveillance colonoscopy should be considered in all patients with at least distal colitis 8 years following symptom onset (with baseline colonoscopy performed at or close to diagnosis). Further intervals between consecutive endoscopies depend on the presence of risk factors including onset before adulthood, duration >10 years, concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), presence of pancolitis or postinflammatory polyps, high disease activity, and possibly a family history of colorectal cancer (Table 7.2-3).

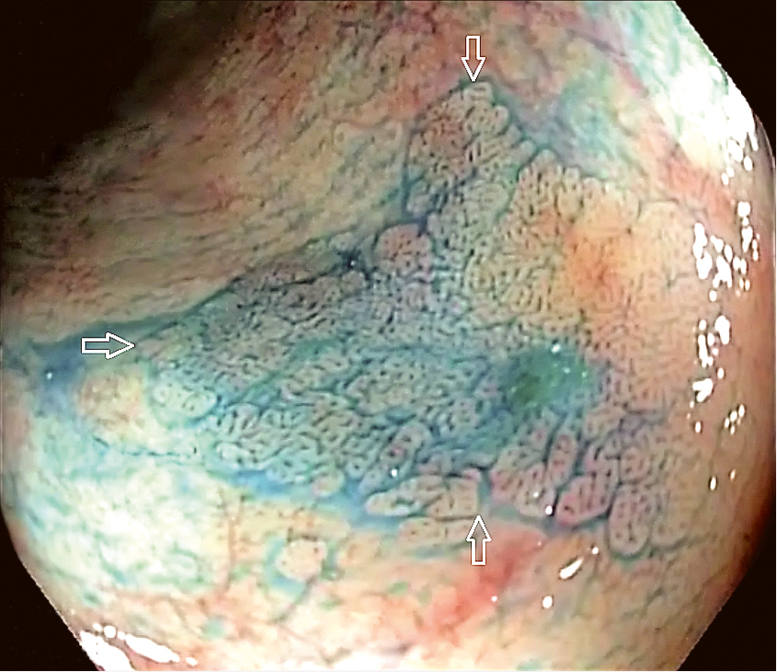

Surveillance colonoscopy is best performed when the patient is in remission. High-definition equipment should be used. In the random biopsy approach, 4-quadrant biopsies are collected from every 10 cm of the intestine along its entire length plus additional samples from suspicious sites (strictures, raised lesions other than postinflammatory polyps). If chromoendoscopy is used (Figure 7.2-20), targeted biopsies are taken only from suspicious areas.

ComplicationsTop

1. Toxic megacolon is a potentially fatal complication occurring in ~3% of patients during a severe (often the first) flare. Clinical manifestations include abdominal pain and distention, high-grade fever, tachycardia, and abdominal signs of peritoneal inflammation. Diagnosis is based on clinical features and plain abdominal radiographs (Figure 7.2-19). Intense supportive care (nasogastric decompression, broad-spectrum antibiotics, hydration) and urgent surgical assessment are required due to a high risk of perforation.

2. Patients with long-standing UC are at increased risk of colorectal cancer, although the magnitude of the increased risk is controversial and lower than previously thought. Predisposing factors include disease duration, disease activity, disease extent, presence of inflammatory polyps, family history of colorectal cancer, and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dysplasia surveillance is indicated (see Follow-Up, above).

Many patients develop inflammatory processes in other organs and systems. Some occur mainly during active disease and do not require specific treatment (eg, peripheral arthritis, iritis, and erythema nodosum), while others (eg, axial arthritis and most hepatobiliary complications) develop independently of colitis activity.

1. Skeletal and articular complications: Arthritis (peripheral or axial; see Enteropathic Arthritis), osteopenia, and osteoporosis.

2. Hepatobiliary complications: Primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis.

3. Cutaneous complications: Erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum.

4. Ocular complications: Iritis, episcleritis.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Assessment |

Points |

|

Stool frequency | |

|

Patient reporting a normal number of daily stools |

0 |

|

1-2 more stools than normal |

1 |

|

3-4 more stools than normal |

2 |

|

≥5 more stools than normal |

3 |

|

Rectal bleeding | |

|

None |

0 |

|

Blood streaks seen with stool less than half of the time |

1 |

|

Blood with most stools |

2 |

|

Pure blood passed |

3 |

|

Endoscopic findings | |

|

Normal or inactive colitis |

0 |

|

Mild friability, erythema, decreased vascularity |

1 |

|

Friability, marked erythema, absent vascular pattern, erosions |

2 |

|

Ulcerations and spontaneous bleeding |

3 |

|

Physician global assessment | |

|

Normal |

0 |

|

Mild colitis |

1 |

|

Moderate colitis |

2 |

|

Severe colitis |

3 |

|

Higher scores are correlated with more severe ulcerative colitis. | |

|

Source: N Engl J Med. 1987;317(26):1625-9. | |

|

Symptoms |

Ulcerative colitis |

Crohn disease |

|

Bleeding |

Common |

Rare |

|

Abdominal pain |

Not severe |

Common and can be severe |

|

Palpable abdominal mass |

Very rare |

Fairly common |

|

Fistulas |

Very rare |

Common |

|

Involvement of the rectum |

95% |

50% |

|

Perianal lesions |

5%-18% |

50%-80% |

|

Postinflammatory polyps |

13%-15% |

Rare |

|

Toxic megacolon |

3%-4% |

Rare |

|

Intestinal perforation |

2%-3% |

Rare |

|

Intestinal stricture |

Rare |

Common |

|

Recommended frequency of surveillance |

Indications |

|

Every 5 years |

– Colitis affecting <50% of the colon surface area – Extensive colitis with mild endoscopic or histologic active inflammation |

|

Every 3 years |

– Postinflammatory polyps – Colorectal cancer in a first-degree relative aged >50 years – Extensive colitis with moderate or severe endoscopic or histologic inflammation |

|

Every year |

– Stricture within the past 5 years – Dysplasia within the past 5 years in a patient who declines surgery – Primary sclerosing cholangitis (including post orthotopic liver transplant), from the time of diagnosis – Colorectal cancer in a first-degree relative aged <50 years |

|

Based on the 2017 European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation guidelines. |

|

Figure 7.2-18. Endoscopic findings in moderate ulcerative colitis. Absent vascular pattern and loss of haustration. The mucosa is friable and bleeds on contact with the endoscope.

Figure 7.2-19. Toxic megacolon seen on a plain abdominal radiograph. The transverse colon is 11 cm in diameter in the midline (arrows).

Figure 7.2-20. A focus of low-grade dysplasia (arrows) revealed by indigo carmine staining.