DuPont HL. Acute infectious diarrhea in immunocompetent adults. N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 17;370(16):1532-40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1301069. Review. PubMed PMID: 24738670.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Definition, criteria, and classification of diarrhea: see Diarrhea.

1. Etiologic agents: Viruses (noroviruses and other caliciviruses; rotaviruses, astroviruses, adenoviruses); bacteria (most commonly Salmonella spp and Campylobacter spp; Escherichia coli, Clostridioides difficile, Yersinia spp, rarely Shigella spp; Listeria monocytogenes); rarely parasites (Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium parvum, Cystoisospora belli [previously known as Isospora belli]; microsporidia).

2. Transmission: Oral route (contaminated hands, food, or water). Typically the source of infection is a sick individual or carrier.

3. Risk factors: Contact with a sick person or carrier; poor hand hygiene; consumption of food and drinking water of dubious origin (potentially contaminated); consumption of raw eggs, mayonnaise, raw or undercooked meat (Salmonella spp), poultry or dairy products (Campylobacter spp, Salmonella spp), seafood (noroviruses), cold meats and aged cheese (L monocytogenes); antibiotic treatment (C difficile); traveling to endemic areas (cholera) and developing countries (traveler’s diarrhea); achlorhydria or gastric mucosal damage (eg, drug-induced); immunodeficiency.

4. Incubation and contagious period: The incubation period lasts a few hours or days. Shedding of the pathogen in feces may continue from a few days to a few months (eg, in the case of Salmonella spp carriers).

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

1. Classification of infectious diarrhea based on pathogenesis:

1) Type I: Enterotoxin-related (eg, enterotoxigenic E coli [ETEC]).

2) Type II: Inflammatory (eg, C difficile).

3) Type III: Invasive (eg, Salmonella spp, Shigella spp, L monocytogenes).

2. Clinical manifestations: Various syndromes may occasionally overlap:

1) Acute gastroenteritis (the most frequent manifestation): Starts with vomiting, which is followed by the development of nonbloody diarrhea without pus and mucus. Patients are at risk of significant dehydration.

2) Dysentery syndrome: Frequent small‑volume bowel movements containing fresh blood or pus and large quantities of mucus, painful and unproductive urge to defecate, and severe abdominal cramping. It may be caused, among others, by Shigella spp or Salmonella spp, enteroinvasive E coli (EIEC), or amebiasis.

3) Typhoid syndrome (enteric fever): The dominant features are high-grade fever (39-40 degrees Celsius), headache, abdominal pain, and relative bradycardia (pulse <100 beats/min with a fever >39 degrees Celsius), which may be accompanied by diarrhea or constipation.

3. Other signs and symptoms: Abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, fever, signs and symptoms of dehydration (the most important and most common complication of acute diarrhea), abdominal tenderness, altered mental status (caused by infection [eg, with Salmonella spp] or dehydration).

4. Natural history: In the majority of patients the disease has a mild course and resolves spontaneously after a few days. A chronic (>1 year) carrier status develops in <1% patients with Salmonella spp infection (rates are higher in patients treated with antibiotics).

DiagnosisTop

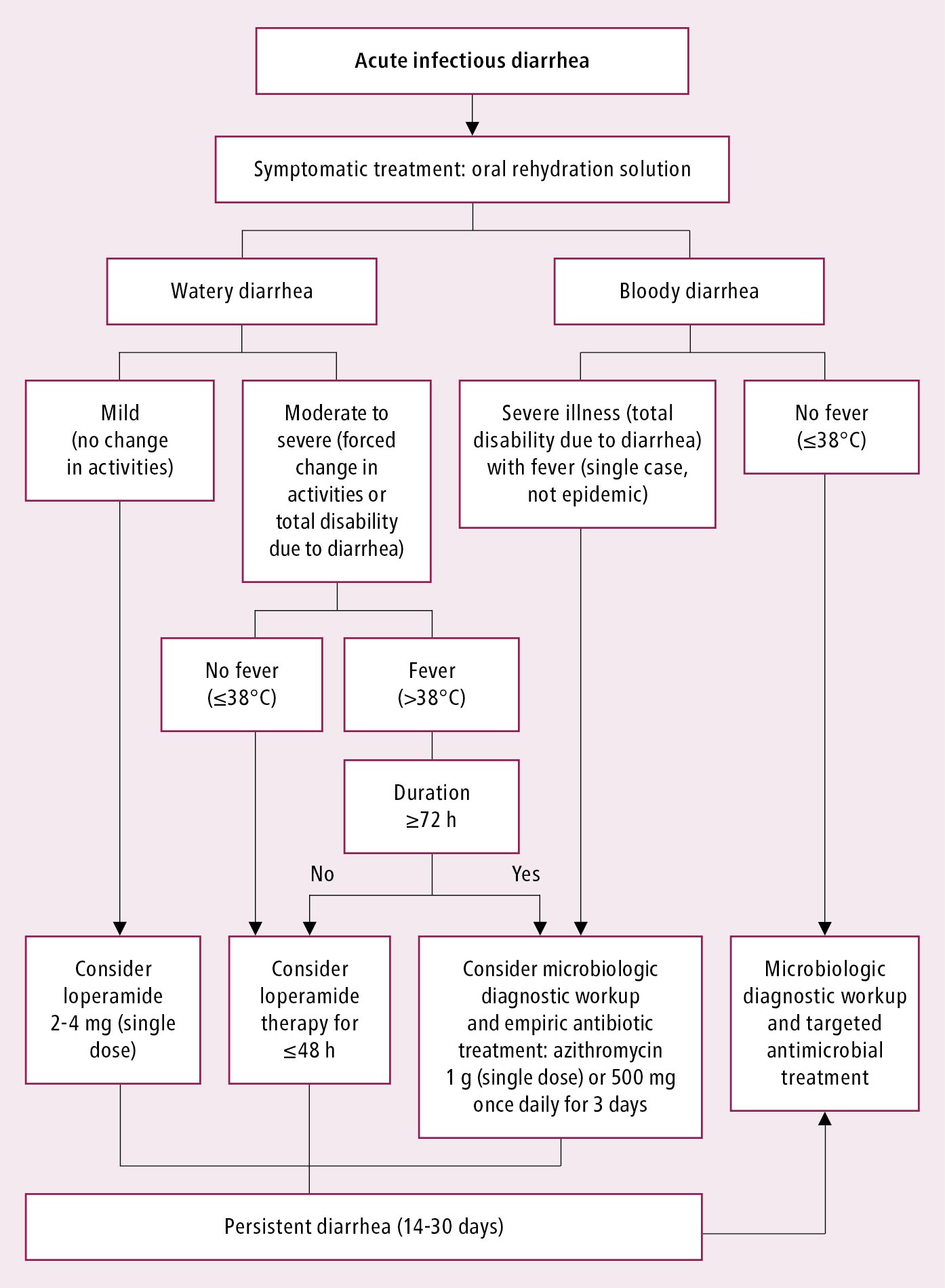

Diagnosis and treatment of infectious diarrhea: Figure 7.2-11. Diagnostic tests are not necessary in the majority of cases, particularly in individuals treated on an outpatient basis. Assess the severity of dehydration in each patient (see Diarrhea).

1. Laboratory tests:

1) Biochemical tests (performed in severely ill or significantly dehydrated patients treated with intravenous fluids) may reveal hypernatremia or hyponatremia (isotonic dehydration is most frequent), hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, metabolic acidosis, and increased levels of urea/blood urea nitrogen (prerenal acute kidney injury).

2) Fecal leukocyte test (a smear of a freshly collected stool specimen stained with 0.5% methylene blue): The presence of ≥5 leukocytes in a high-power field indicates inflammatory or invasive diarrhea (in the case of amebiasis despite dysentery no neutrophils are found in stool but erythrocytes are present). The test should be performed on a fresh stool sample.

3) Fecal lactoferrin: A positive result is suggestive of inflammatory or invasive diarrhea of a bacterial etiology (there is no need for urgent shipment of the stool samples to the laboratory as lactoferrin is released by disintegrating neutrophils).

2. Stool microbiology: Bacterial cultures (may be repeated a few times because pathogen shedding is not continuous), in justified cases followed by parasitology and virology studies. Indications for microbiological stool testing include dysentery, high numbers of neutrophils in stools or positive test results for fecal lactoferrin, severe diarrhea with severe dehydration and fever, suspected nosocomial diarrhea, diarrhea persisting for >2 weeks, extraintestinal signs and symptoms (eg, arthritis in Salmonella spp, Campylobacter spp, Shigella spp, or Yersinia spp infections), epidemiologic reasons (eg, epidemiologic investigation; suspicion of cholera, typhoid fever, or type A, B, or C paratyphoid fever; testing for the possible carrier status in carriers and convalescents with a history of cholera, typhoid fever, paratyphoid fever, salmonellosis, or shigellosis, as well as in individuals who may be at risk of infecting others due to their occupation).

Other causes of acute diarrhea (see Diarrhea).

TreatmentTop

The majority of patients may be treated on an outpatient basis. Indications for hospitalization may include need for intravenous fluid treatment, suspected bacteremia, complications of infectious diarrhea, enteric fever syndrome (typhoid fever; paratyphoid fever A, B, or C), immunocompromised patients, and stays in areas endemic for cholera.

1. Fluid replacement therapy is the mainstay of symptomatic treatment (see Diarrhea).

2. Nutritional management: After a successful fluid therapy (3-4 hours) resume oral nutrition as tolerated. A potential diet may be based on foods rich in boiled starch (rice, pasta, potatoes) and on groats, with an addition of crackers, bananas, natural yoghurt, soups, and boiled meats and vegetables. Spices should be avoided if they are not tolerated. Patients should consume meals according to their preferences but avoid heavy, fried foods and sweetened milk. Frequent smaller meals are beneficial. A regular diet may be reintroduced as soon as stools become well formed.

3. Antidiarrheal drugs: Loperamide (see Diarrhea). Antidiarrheal drugs should be reserved for the second-line therapy and avoided in patients with infectious diarrhea.

4. Probiotics: Some probiotics (Lactobacillus casei GG, Saccharomyces boulardii) may be a beneficial addition to the treatment of watery diarrhea of a confirmed or suspected viral etiology. Oral administration of one sachet or capsule bid reduces the duration of diarrhea by 1 to 2 days.Evidence 1Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to methodological shortcomings (risk of bias), variability in definition of diarrhea and choice of probiotics, and most data coming from pediatric population. Allen SJ, Martinez EG, Gregorio GV, Dans LF. Probiotics for treating acute infectious diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Nov 10;(11):CD003048. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003048.pub3. Review. PubMed PMID: 21069673. Probiotics are not effective in inflammatory and invasive diarrhea (types II and III).

5. Management of other disturbances (metabolic acidosis, electrolyte disturbances): see Water and Electrolyte Disturbances.

Indications for antimicrobial treatment are limited because in the majority of cases infectious diarrhea resolves spontaneously.

1. Empiric antimicrobial treatment should be considered in patients with traveler’s diarrhea and while awaiting results of stool cultures in patients with severe inflammatory diarrhea (associated with fever, painful urge to defecate, blood or leukocytes in stools, positive results of fecal lactoferrin test, ie, features typical for infection with Salmonella spp, Campylobacter jejuni, Yersinia spp, or Shigella spp). Use an oral quinolone for 3 to 5 days (ciprofloxacin 750 mg once daily or 500 mg bid, norfloxacin 800 mg once daily or 400 mg bid, or ofloxacin 400 mg once daily or 200 mg bid) or azithromycin (1 g in a single dose or 500 mg/d for 3 days). Do not use these agents in afebrile patients with dysentery, as it may have been caused by enterohemorrhagic E coli (EHEC) (see below).

2. Targeted antimicrobial treatment:

1) Salmonella spp (other than Salmonella Typhi): Treatment is not indicated in patients with asymptomatic or mild infection; however, it should be started in patients with severe disease, sepsis, or risk factors for extraintestinal infection (see Complications, below). Use oral ciprofloxacin (dosage as above) for 5 to 7 days; alternatively use azithromycin 1 g followed by 500 mg once daily for 6 days or a third-generation cephalosporin (eg, ceftriaxone 1-2 g/d).

2) S Typhi: Use a fluoroquinolone for 10 to 14 days (ciprofloxacin as above, norfloxacin 400 mg bid); alternatively use azithromycin 1 g followed by 500 mg once daily for 6 days or a third-generation cephalosporin (eg, ceftriaxone 1-2 g/d). Rise in quinolone resistance and multiresistant isolates from Southeast Asia and Africa must be taken into account based on the patient’s travel history.

3) C jejuni: Use azithromycin (1 g in a single dose or 500 mg once daily for 3 days) or a fluoroquinolone for 5 days (eg, ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin as above).

4) Shigella spp: Use a fluoroquinolone bid for 3 days (ciprofloxacin 500 mg, ofloxacin 300 mg, or norfloxacin 400 mg); alternatively use azithromycin 500 mg in a single dose followed by 250 mg once daily for 4 days or a third-generation cephalosporin (eg, ceftriaxone 1-2 g/d).

5) E coli:

a) ETEC, enteropathogenic E coli (EPEC), and EIEC, as well as Aeromonas spp and Plesiomonas spp: Use trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 180/800 mg or a fluoroquinolone bid for 3 days (eg, ofloxacin 300 mg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg, norfloxacin 400 mg).

b) Enteroaggregative E coli strains (EAggEC): Generally antimicrobial treatment is not recommended as the effects are unknown.

c) EHEC: Avoid drugs that may inhibit peristalsis and antibiotics because of their undetermined role in the treatment and a risk of hemolytic-uremic syndrome.

6) Yersinia spp: Antibiotics are usually not necessary. In patients with severe infection or bacteremia, use doxycycline combined with an aminoglycoside, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, or a third-generation cephalosporin.

7) Vibrio cholerae strains O1 or O139: Ciprofloxacin 1 g once daily, alternatively doxycycline 300 mg once daily or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (160 mg trimethoprim) bid for 3 days.

8) L monocytogenes: Usually no treatment is required as the infection is self-limiting. If it persists or in the case of an immunocompromised host, use oral amoxicillin 500 mg tid or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (160 mg trimethoprim) bid for 7 days.

9) Giardia lamblia: Acceptable options include oral metronidazole 250 mg tid for 5 to 7 days, oral tinidazole as a single dose of 2 g, or nitazoxanide 500 mg bid for 3 days. In pregnant patients use oral paromomycin 10 mg/kg tid for 5 to 10 days.

10) Cryptosporidium spp: In patients with severe infection, use paromomycin 500 mg tid for 7 days.

11) Cystoisospora (Isospora) spp, Cyclospora spp: Use trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (160 mg trimethoprim) bid for 7 to 10 days; this is not recommended in patients with microsporidia infections.

ComplicationsTop

Complications depend on etiology and include:

1) Hemorrhagic colitis (EHEC, Shigella spp, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Campylobacter spp, Salmonella spp).

2) Toxic megacolon, intestinal perforation (EHEC, Shigella spp, C difficile, Campylobacter spp, Salmonella spp, Yersinia spp).

3) Hemolytic-uremic syndrome (EHEC serotype O157:H7 and Shigella spp, rarely Campylobacter spp).

4) Reactive arthritis (Shigella spp, Salmonella spp, Campylobacter spp, Yersinia spp).

5) Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (Campylobacter spp, Shigella spp, Salmonella spp).

6) Distant localized extraintestinal infections (meningitis, encephalitis, osteitis, arthritis, wound infection, cholecystitis, abscesses in various organs) or sepsis (Salmonella spp, Yersinia spp, rarely Campylobacter spp or Shigella spp). Risk factors are age <6 months or >50 years, prosthetic implants, congenital or acquired heart disease, severe atherosclerosis, malignancy, uremia, immunodeficiency, diabetes mellitus, and iron overload (increased risk of severe infection with certain pathogens, including Yersinia spp, Listeria monocytogenes, Vibrio cholera, E coli).

7) Malnutrition and cachexia (various pathogens).

8) Guillain-Barré syndrome (C jejuni).

PrognosisTop

In the majority of patients the prognosis is good. However, elderly patients are at risk of severe disease and death.

PreventionTop

The key prevention measures include:

1) Good hand hygiene: Thorough hand washing with soap and water after defecation, after changing soiled diapers, after any contact with toilet/washroom facilities, before meal preparation and consumption, after handling raw meat and eggs.

2) Regular sanitary inspections, adherence to food and water safety guidelines (concerning both production and distribution).

3) Mandatory notification of local public health authorities for reportable pathogens (may vary among jurisdictions), epidemiologic vigilance, identification of sources of infection (epidemiologic investigations).

4) Carrier status testing in carriers if applicable based on public health regulations.

FiguresTop

Figure 7.2-11. Management algorithm in patients with infectious diarrhea.