Internal Medicine Rapid Refreshers is a series of concise information-packed videos refreshing your knowledge on key medical issues that general practitioners may encounter in their daily practice. This video highlights the important aspects of assessing and managing atrial fibrillation.

Contents

- Overview

- Assessment and management

- Assessment and management: Is it AF?

- Assessment and management: Stable vs unstable

- Assessment and management: Rate vs rhythm control

- Assessment and management: Identifying etiology

- Assessment and management: Anticoagulation

- Credits and resources

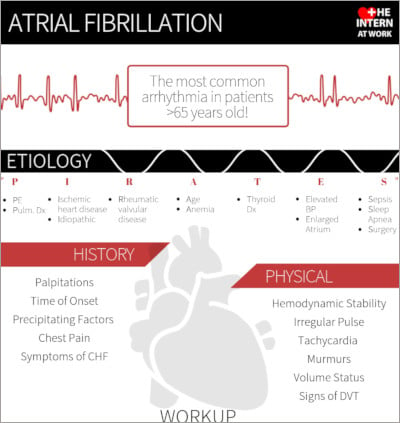

Infographic

Click to view the full image.

Infographic courtesy of The Intern at Work (theinternatwork.com).

Useful links

- Chapter on atrial fibrillation from the McMaster Textbook of Internal Medicine

- Podcast on atrial fibrillation from The Intern at Work

- 2018 guideline update for the management of atrial fibrillation by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society

- Tachycardia with a pulse algorithm from ACLS.com

Transcript

Introduction

I’m Heather Bannerman, a senior medical resident from McMaster University. In this video we will go through a practical approach to atrial fibrillation. This refresher is intended for physicians who are returning to general internal medicine. This is not meant to serve as medical advice to the general population.

Overview

Atrial fibrillation (AF, also AFib) is the most common arrhythmia in adults >65 years of age. AF can be classified as valvular or nonvalvular. Valvular AF occurs in the presence of mechanical heart valves, rheumatic mitral stenosis, or moderate to severe nonrheumatic mitral stenosis. It is important to distinguish between these two types because it affects treatment.

Assessment and management

Questions to consider in the assessment and management of AF:

- Is it AF?

- Is the patient stable or unstable clinically?

- Should we attempt rate or rhythm control?

- What is the underlying etiology or trigger?

- What anticoagulation should be used?

1. Is it AF? In AF electrocardiography (ECG) will show an irregularly irregular rhythm and the absence of P waves. On history, ask the patient about signs and symptoms including palpitations, chest discomfort, syncope, and symptoms of congestive heart failure (CHF). Ask about the timing of the onset of these symptoms and if the patient has any history of AF. On physical examination, feel for pulse irregularity, listen for a variable S1, listen for murmurs, complete a volume status examination, and look for signs of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), as pulmonary embolism (PE) can be a trigger for new AF.

2. Stable or unstable: The question of whether the patient is stable or unstable is very important. Signs of instability include hypotension, acutely altered mental status, signs of shock, ischemic chest discomfort, or acute heart failure. These patients will require immediate electrical cardioversion. The need for emergency cardioversion usually requires the presence and assistance of others, such as the emergency room physician, cardiologist, and rapid response team. These patients will need to be in a bed with cardiac monitoring. Make sure to have 2 peripheral intravenous (IV) lines, oxygen monitors, and frequent blood pressure monitoring. Ask for assistance from an experienced physician (emergency room physicians, anesthesiologists) for sedation.

3. Rate or rhythm control: As mentioned previously, all patients who are unstable should be cardioverted. For stable patients, you can use rate or rhythm control, as they have been shown to be equally effective in the long term. Remember that all of these patients should be on a cardiac monitor.

Rhythm control refers to converting the underlying rhythm back to normal sinus rhythm. People who may benefit more from rhythm control include younger patients and those who are symptomatic despite rate control. Rhythm control can be achieved with electrical or pharmacologic methods.

If planning elective electrical or pharmacologic cardioversion, you will need to anticoagulate the patient for ≥3 weeks before cardioversion (and for ≥4 weeks after) in the following cases:

- Valvular AF (of any duration).

- Nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) lasting <12 hours with recent stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA).

- NVAF lasting 12 to 48 hours and a CHADS2 score ≥2.

- NVAF lasting >48 hours.

The most common pharmacologic agent used in the hospital for cardioversion is amiodarone. It is given as 150 mg IV as a single dose over 10 minutes. This can be repeated × 1. If there is no significant effect, an IV infusion of 900 mg over 24 hours can be given. For other options, discuss with a cardiologist, as there are more effective agents available, like procainamide (15 mg/kg IV in slow infusion) or propafenone or flecainide (300 mg orally).

Rate control refers to a treatment strategy of lowering the heart rate in AF to allow for optimal cardiac filling. Your goal for rate control is to keep the heart rate <110 beats/min with no symptoms. Your options for rate control include beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, or digoxin.

Depending on how urgently you need to bring the heart rate down, you can use IV or oral agents. Remember that beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers will also decrease blood pressure. Doses for common rate control agents:

| Table. Atrial fibrillation: Common rate control agents | |

|---|---|

| Metoprolol | – 2.5-5 mg IV over 2 min; can be repeated every 5 min (max, 15 mg) – 12.5-100 mg PO bid |

| Diltiazem | – 0.25 mg/kg IV (max, 20 mg) over 10 min, repeat at 0.35 mg/kg (max, 30 mg) – 120-480 mg PO daily in long-acting formulation (can be divided qid in short-acting formulation) |

| Digoxin | 0.5 mg IV loading dose followed by 0.25 mg IV every 6 h × 2 |

| PO, oral; qid, 4 times a day. | |

Be careful using these atrioventricular (AV) node–blocking agents in patients with AF and a wide QRS complex. This is because patients with preexcitation syndromes (eg, Wolff-Parkinson-White [WPW] syndrome) plus AF will have a wide complex and using these types of AV node–blocking agents may cause the accessory pathway to conduct at the atrial rate of 400 to 600 beats/min. Look at old ECGs. If the patient had a previous left bundle branch block (LBBB) or right bundle branch block (RBBB), then the wide complex is likely due to the block and you don’t have to worry. If the old ECGs show slurring of the upstroke of the QRS complex (delta wave), they may have underlying WPW syndrome. If you are unsure, always ask for help.

4. Identify the underlying etiology or trigger: When working up a patient with AF, consider the underlying etiology. A useful acronym is “PIRATES”:

- P = PE, pulmonary disease

- I = ischemia, idiopathic

- R = rheumatic valvular disease

- A = age, anemia

- T = thyroid disease

- E = elevated blood pressure, enlarged atrium, ethanol (± drugs)

- S = sepsis, sleep apnea, surgery

Do not forget about medication errors or medication interruption, which can happen postoperatively.

Investigations you should order to look for the underlying etiology include a complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, extended electrolytes, creatinine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Look for any ischemic changes on ECG and include troponin levels in the initial work-up. A chest x-ray is often useful, especially if the patient has respiratory symptoms that may suggest an infection or CHF. Keep PE in your differential diagnosis and look for signs and symptoms of DVT.

5. Anticoagulation: Use the CHADS-65 algorithm (from the Canadian Cardiovascular Society; linked above) for decision-making regarding anticoagulation in AF. This consists of age ≥65 years, prior stroke or TIA, hypertension, heart failure, or diabetes. Patients with a score ≥1 or aged ≥65 years should be on oral anticoagulation for stroke prevention.

For most patients, the first line is a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC), such as apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, or edoxaban. However, for valvular AF, only warfarin is indicated. Doses of the DOAC medications:

| Table. Atrial fibrillation: Doses of direct oral anticoagulants | |

|---|---|

| Apixaban | – 5 mg PO bid – 2.5 mg PO bid if 2/3 of age >80, <60 kg, Cr >133 micromol/L |

| Rivaroxaban | – 20 mg PO daily – 15 mg PO daily if CrCl 30-49 mL/min |

| Dabigatran | – 150 mg PO bid – 110 mg PO bid if age >75 or CrCl 30-49 mL/min |

| Edoxaban | – 60 mg PO daily – 30 mg PO daily if CrCl 30-50 mL/min, <60 kg, or use of potent PGP inhibitors |

| bid, 2 times a day; CrCl, creatinine clearance; PGP, P-glycoprotein; PO, oral. | |

Credits and resources

Thank you for watching this Rapid Refresher video on AF. I would like to thank Doctor Syamkumar Divakaramenon (Division of Cardiology; consultant for this video) and Doctor Roman Jaeschke (Divisions of Critical Care and Internal Medicine; editor for this video).

The resources used are linked above and include the Canadian Cardiovascular Society guideline, the podcast on AF from The Intern at Work, the chapter on AF from the McMaster Textbook of Internal Medicine, and an algorithm from ACLS.com.

English

English

Español

Español

українська

українська