Van Gelder IC, Rienstra M, Bunting KV, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2024;45(36):3314-3414. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehae176

Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation. 2024 Jan 2;149(1):e167. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001207.] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2024 Feb 27;149(9):e936. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001218.] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2024 Jun 11;149(24):e1413. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001263.]. Circulation. 2024;149(1):e1-e156. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193

Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 14;42(35):3427-3520. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab364. PMID: 34455430.

Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021 Feb 1;42(5):373-498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021 Feb 1;42(5):507. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021 Feb 1;42(5):546-547. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021 Oct 21;42(40):4194. PMID: 32860505.

Andrade JG, Aguilar M, Atzema C, et al. The 2020 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society Comprehensive Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Dec;36(12):1847-1948. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2020.09.001. Epub 2020 Oct 22. PMID: 33191198.

Brugada J, Katritsis DG, Arbelo E, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia: The Task Force for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2020 Feb 1;41(5):655-720. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz467. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2020 Nov 21;41(44):4258. PMID: 31504425.

January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jul 9;74(1):104-132. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.011. Epub 2019 Jan 28. Erratum in: J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jul 30;74(4):599. PMID: 30703431.

Kusumoto FM, Schoenfeld MH, Barrett C, et al. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline on the evaluation and management of patients with bradycardia and cardiac conduction delay: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2019 Sep;16(9):e128-e226. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.10.037. Epub 2018 Nov 6. PMID: 30412778.

January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014 Dec 2;130(23):e199-267. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041. Epub 2014 Mar 28. Erratum in: Circulation. 2014 Dec 2;130(23):e272-4. PMID: 24682347; PMCID: PMC4676081.

Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm. 2013 Dec;10(12):1932-63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.05.014. Epub 2013 Aug 30. Review. PMID: 24011539.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Atrial flutter (AFL) is a macroreentrant arrhythmia (spinning around a large circuit in the atrium) characterized by a regular atrial rate (usually 250-300 beats/min) and a constant P wave morphology. Paroxysmal AFL can occur in patients with no apparent structural heart disease, whereas chronic AFL is usually associated with preexisting conditions, such as valvular or ischemic heart disease or cardiomyopathy. Those at the highest risk of developing AFL are men, older adults, and individuals with preexisting heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In ~60% of cases AFL occurs as part of an acute disease process. The same risk factors that increase the risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) also apply to AFL.

In >90% of patients with AFL, the AFL circuit involves the cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI), which is the critical area for sustaining the flutter and where efforts to ablate may be directed. AFL can occur in clinical settings similar to those associated with atrial fibrillation (AF) and may be triggered by atrial tachycardia (AT) or AF. Non–CTI-dependent flutter is called atypical and is commonly seen in patients with previous AF ablation, severe left atrial disease, or previous atrial surgery.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

AFL is frequently recurrent and attacks are usually accompanied by tachyarrhythmia. Some patients may be asymptomatic in chronic AFL. Antiarrhythmic drugs and heart rate medications are less effective in AFL than in other types of supraventricular arrhythmias and thus the general recommendation is to either combine atrioventricular (AV) nodal blockers if rate control is intended or consider electrical cardioversion.

In individuals with AF treated with class Ic drugs (see Table 3.4-1) there is a small risk of AF organizing into AFL, and this is the reason why flecainide should always be associated with an AV nodal blocker. This is not the case for propafenone.

Clinical signs and symptoms largely depend on the type and severity of the underlying condition and include palpitations (most commonly), dyspnea, weakness, or chest pain. Some patients may be asymptomatic. Heart rates are fast (~150 beats/min) and regular.

DiagnosisTop

Electrocardiography (ECG): The AFL waves are due to rapidly reoccurring atrial depolarizations without isoelectric baseline between the consecutive waves. This gives the “saw tooth” or “picked fence” pattern to this arrhythmia. Typical AFL (CTI-dependent, counterclockwise rotation around the tricuspid valve) is characterized by dominant negative flutter waves in the inferior leads and a positive P wave in lead V1. Reverse typical AFL (CTI-dependent, counterclockwise rotation around the valve) shows the opposite pattern, with a positive flutter wave in the inferior leads and a negative P wave in lead V1. Carotid sinus massage or adenosine can be useful to transiently increase the degree of the AV block and facilitate diagnosis.

Supraventricular tachycardia: see Figure 3.4-2. Narrow-QRS tachycardia: see Figure 3.4-3. Wide-QRS tachycardia: see Figure 3.4-4.

TreatmentTop

Classification of antiarrhythmic drugs: see Table 3.4-1.

Antiarrhythmic agents: see Table 3.4-2.

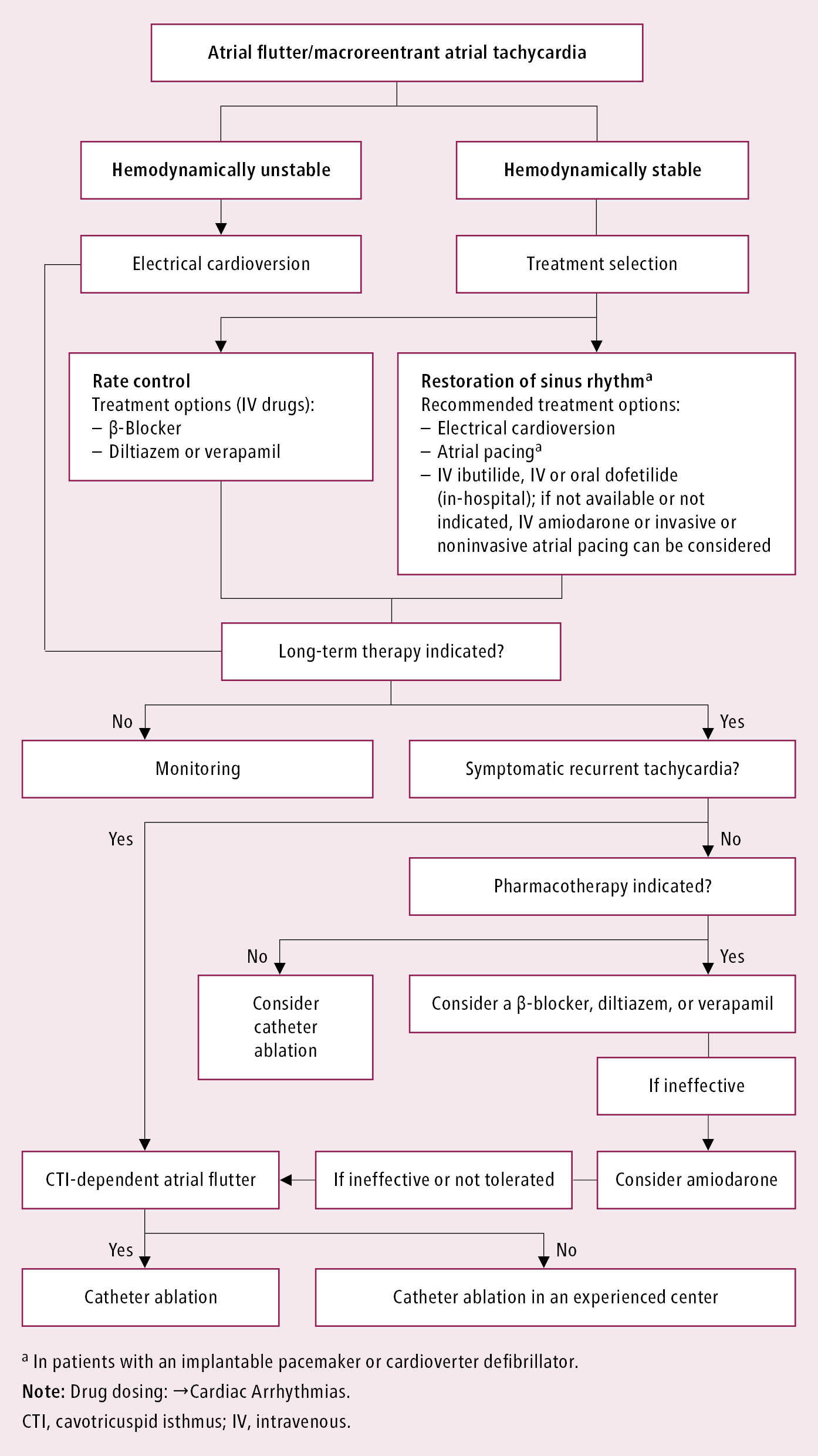

AFL treatment algorithm: Figure 3.4-9.

1. Electrical cardioversion: AFL does not respond well to drugs in general. Electrical cardioversion should be considered early in the management of patents with AFL. Usually a low-energy (50-100 J) shock is used. Prevention of thromboembolism is used as in AF (see Atrial Fibrillation).

2. Pharmacologic treatment: Figure 3.4-9.

Guidelines for drug selection (Figure 3.4-9) are similar to those used in AF, but the effectiveness of antiarrhythmic drugs is significantly inferior to ablation and lower than when used for AF. Rate control may also be difficult to achieve in AFL. In CTI-dependent AFL, catheter ablation has a high success rate with a very low complication rate and may be offered even to patients after a first well-tolerated AFL attack. In atypical AFL, ablation is a more complex procedure with higher recurrence rates and should be considered depending on the patient’s profile.

ComplicationsTop

AFL increases the risk of thromboembolic complications, including ischemic stroke. Therefore, thromboembolism prevention is required, as in patients with AF (see Atrial Fibrillation).

FiguresTop

Figure 3.4-9. Treatment of macroreentrant atrial tachycardia. Based on the 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines.