Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 14;42(35):3427-3520. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab364. PMID: 34455430.

Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021 Feb 1;42(5):373-498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021 Feb 1;42(5):507. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021 Feb 1;42(5):546-547. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021 Oct 21;42(40):4194. PMID: 32860505.

Andrade JG, Aguilar M, Atzema C, et al. The 2020 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society Comprehensive Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Dec;36(12):1847-1948. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.09.001. Epub 2020 Oct 22. PMID: 33191198.

Brugada J, Katritsis DG, Arbelo E, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia. The Task Force for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2020 Feb 1;41(5):655-720. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz467. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2020 Nov 21;41(44):4258. PMID: 31504425.

January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jul 9;74(1):104-132. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.011. Epub 2019 Jan 28. Erratum in: J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jul 30;74(4):599. PMID: 30703431.

Kusumoto FM, Schoenfeld MH, Barrett C, et al. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline on the evaluation and management of patients with bradycardia and cardiac conduction delay: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2019 Sep;16(9):e128-e226. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.10.037. Epub 2018 Nov 6. PMID: 30412778.

January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014 Dec 2;130(23):e199-267. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041. Epub 2014 Mar 28. Erratum in: Circulation. 2014 Dec 2;130(23):e272-4. PubMed PMID: 24682347; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4676081.

Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm. 2013 Dec;10(12):1932-63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.05.014. Epub 2013 Aug 30. Review. PubMed PMID: 24011539.

Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES); Heart Rhythm Society (HRS); American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF); American Heart Association (AHA); American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP); Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS), Cohen MI, Triedman JK, Cannon BC, et al. PACES/HRS expert consensus statement on the management of the asymptomatic young patient with a Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW, ventricular preexcitation) electrocardiographic pattern: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS). Heart Rhythm. 2012 Jun;9(6):1006-24. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.050. Epub 2012 May 10. PubMed PMID: 22579340.

DefinitionTop

1. Supraventricular arrhythmias:

1) Supraventricular premature beats (SPBs) originate in the atrium but outside the sinus node. They are either premature or escape beats and may be single or multiple. They may occur randomly or in an organized pattern after every normal sinus beat (bigeminy) or after every 2 normal sinus beats (trigeminy).

2) Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is any tachycardia >100 beats/min that originates above the bundle of His, including:

a) Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT).

b) Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT).

c) Atrial tachycardia (AT).

3) Atrial flutter (AFL).

4) Atrial fibrillation (AF).

2. Ventricular arrhythmias originate from the ventricles:

1) Ventricular premature beats (VPBs) may be premature or escape beats. They may also be monomorphic (all VPBs have the same morphology) or polymorphic (several VPB morphologies) and single or complex. They may occur after every normal sinus beat (bigeminy) or after every 2 normal sinus beats (trigeminy).

2) Ventricular tachycardia (VT): Nonsustained VT will last <30 seconds. Sustained VT is defined as lasting >30 seconds or shorter if it causes hemodynamic compromise.

3) Ventricular fibrillation (VF): Very rapid and uncoordinated contractions of the heart ventricles, unable to generate an effective pulse beat.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

1. Supraventricular arrhythmias: Signs and symptoms depend on the ventricular rate, underlying heart disease, arrhythmia duration, and patient’s individual sensitivity to arrhythmia. While SVTs are more commonly seen in normal hearts and younger patients, AF and AFL usually occur in hypertensive or structural heart disease and in older individuals. Symptoms include palpitations, dizziness, chest discomfort, dyspnea, and near-fainting or syncope. SVT is usually paroxysmal (characterized by a sudden onset and resolution) and can recur with varying frequency. AFL and AF can progress from the paroxysmal form into a more persistent and permanent form (the patient is mainly in AF instead of sinus rhythm). AF and AFL also carry a risk of embolic stroke. Rarely, persistent supraventricular arrhythmia with rapid ventricular rates may cause tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy and heart failure symptoms.

2. Ventricular arrhythmias: Ventricular arrhythmias in the form of VPBs or nonsustained VT can be asymptomatic. However, patients may have symptoms like palpitations, dizziness, chest discomfort, dyspnea, and near-fainting or syncope. There is an inconsistent correlation between the amount of ectopic beats (percentage of VPBs or nonsustained VT of all beats) and symptoms. In structurally normal hearts even a sustained episode of VT can cause no symptoms; however, the majority of sustained VT episodes are symptomatic and can cause syncope or cardiac arrest. VF is a terminal arrhythmia unless the patient is resuscitated.

DiagnosisTop

The key for diagnosing arrhythmia is its electrocardiographic (ECG) appearance. Nevertheless, a proper physical examination can be essential for diagnosis when assessing for pulse rate, rhythm, and signs of structural heart disease (eg, valvular disease, heart failure). At times a few other diagnostic tests can be useful.

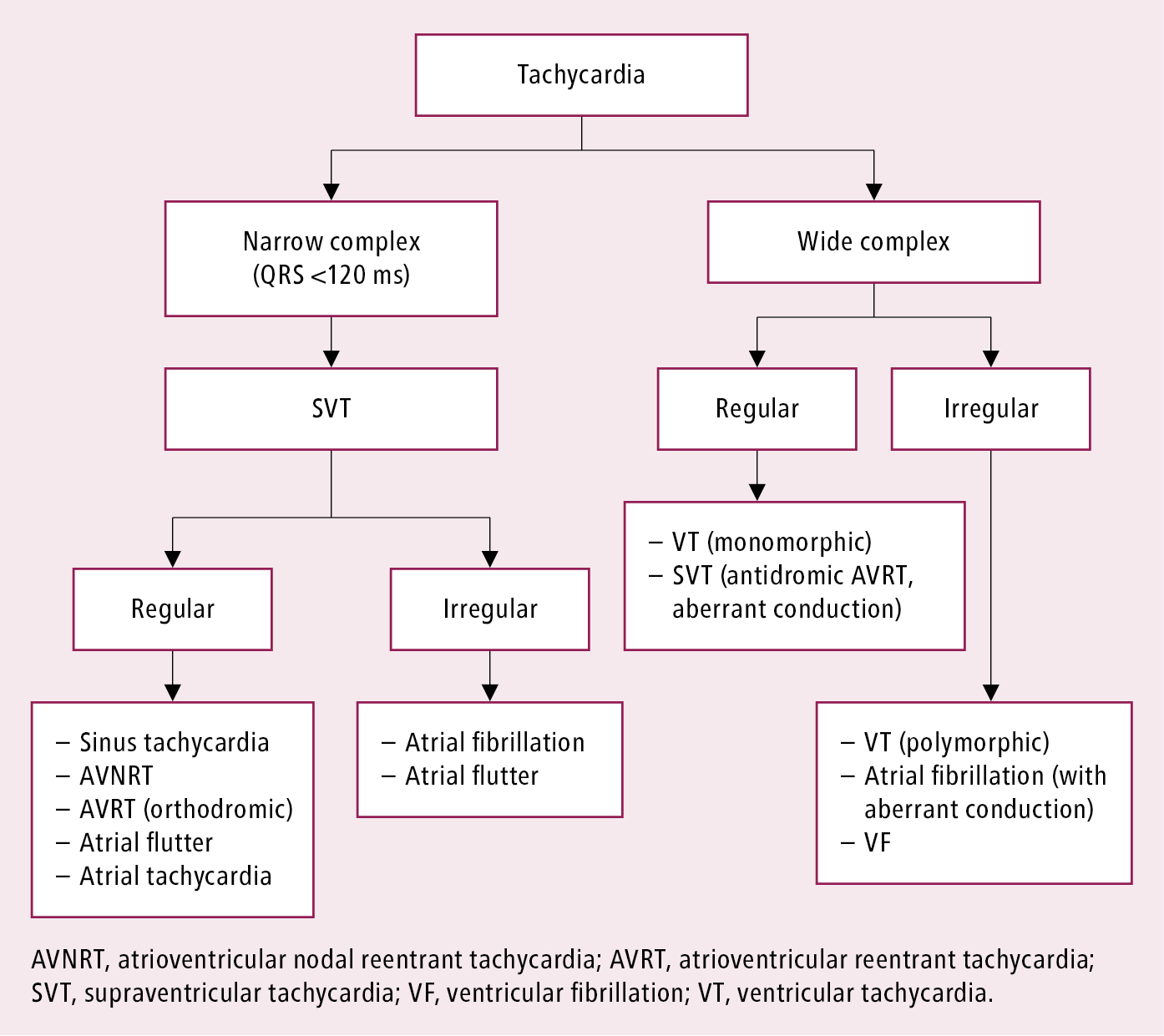

The ECG appearance of arrhythmia can lead to a correct diagnosis (Figure 3.4-1). When analyzing the ECG, the following should be taken into consideration:

1) Assess the rate (tachycardia vs bradycardia).

2) Assess the QRS-complex width (wide vs narrow).

3) Assess regularity. If the rhythm is irregular, is there a pattern?

4) Look for P waves:

a) Assess the relation of P waves to QRS complexes.

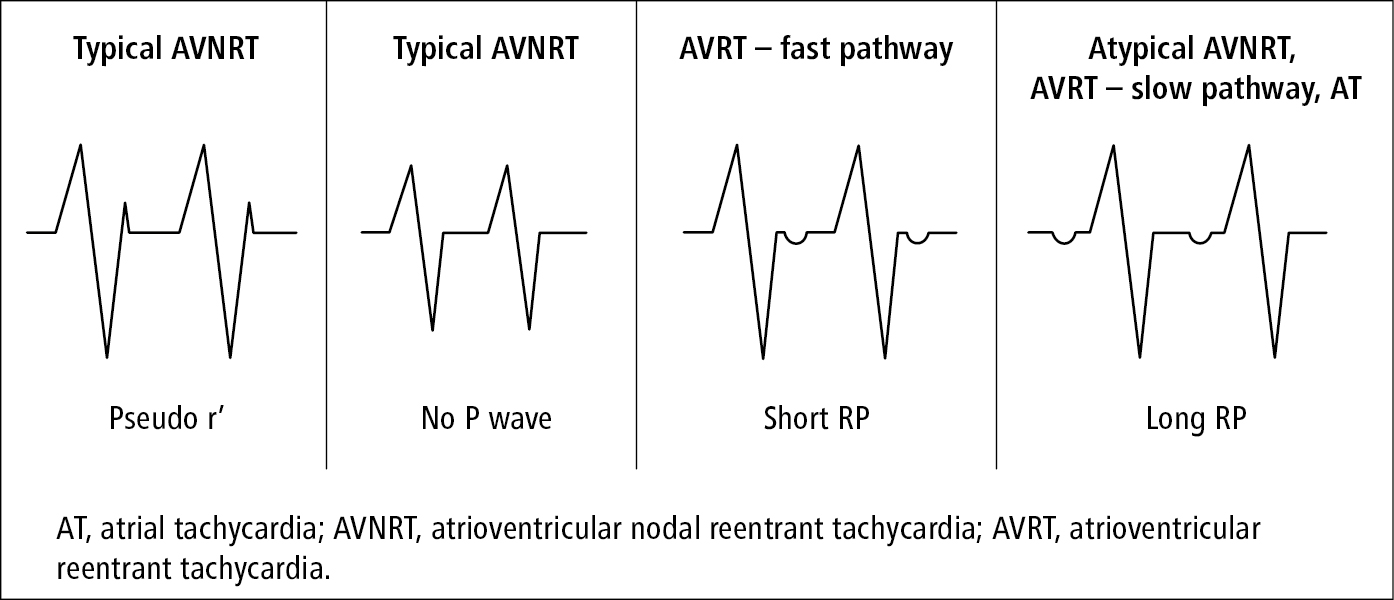

b) If the relation is 1:1, assess the timing of P waves in relation to the previous QRS complex (short RP vs long RP; Figure 3.4-2).

1. ECG:

1) 12-lead resting ECG.

2) Continuous ECG monitoring is useful in patients with frequent episodes of arrhythmia. For outpatients, Holter monitors can accumulate continuous ECG information from 24 hours and up to a week. The data are then downloaded and arrhythmias are identified offline. This can also aid in assessing the number of ectopic beats (SPBs or VPBs in 24 hours), their type (single or complex, nonsustained or sustained VT), circadian pattern, and is useful in assessing for slow heart rates (bradycardia) and pauses. Holter monitors are also helpful in the evaluation of QT-segment prolongation, Brugada syndrome ECG patterns, and numerous investigational prognostic markers in structural heart disease (eg, heart rate variability). Inpatients can be monitored by continuous telemetry ECG monitoring; some of these systems offer storing and processing of data on top of real-time alerting for arrhythmias.

3) Long-term ECG recorders come in the form of loop or event recorders. These devices will keep on recording and deleting a few minutes of ECG unless an arrhythmia is detected. Usually when using a remote device the patient can also instruct it to store an episode of ECG when symptomatic, even after regaining consciousness from a fainting spell. The last few minutes of the ECG are thus stored and can be also transmitted. These devices can be external (using ECG electrodes on the chest skin similar to a Holter device) or internal (implantable loop recorder [ILR]) and are used for detecting arrhythmias in patients with infrequent symptoms. Implantable recorders can last for a few years.

4) ECG stress testing is used in the diagnosis of arrhythmias in patients with symptoms that are either related to or exacerbated on exertion.

2. Electrophysiologic study (EPS) is an invasive study, usually combined with a therapeutic intervention, used for making a detailed diagnosis of arrhythmia. Electrodes (catheters) are introduced into the heart via the venous (usually) or arterial approach.

3. Echocardiography is often used to assess for structural heart disease (eg, cardiac function, hypertrophy, valvular disease), which can help in the identification of causes or complications of an arrhythmia (eg, tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy).

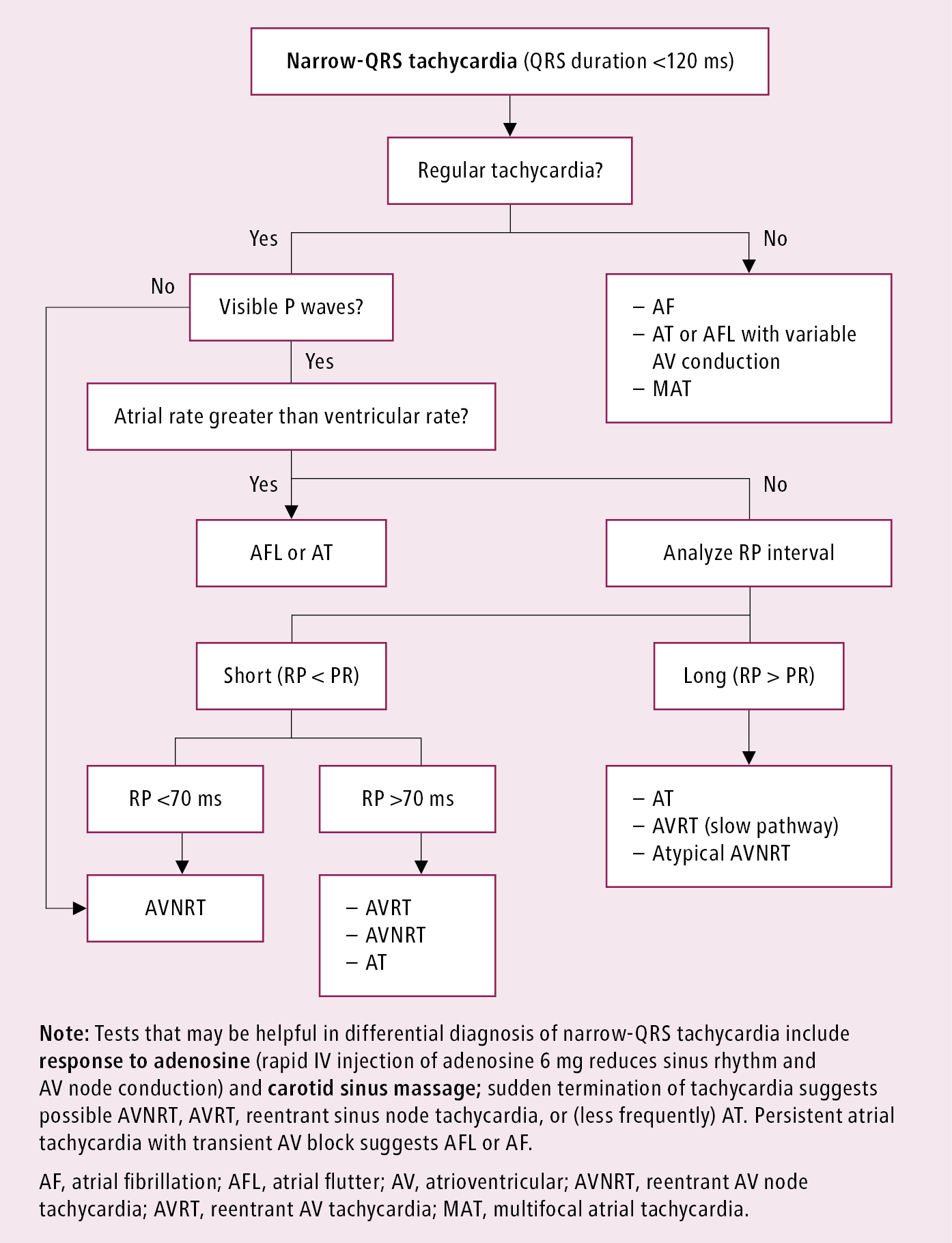

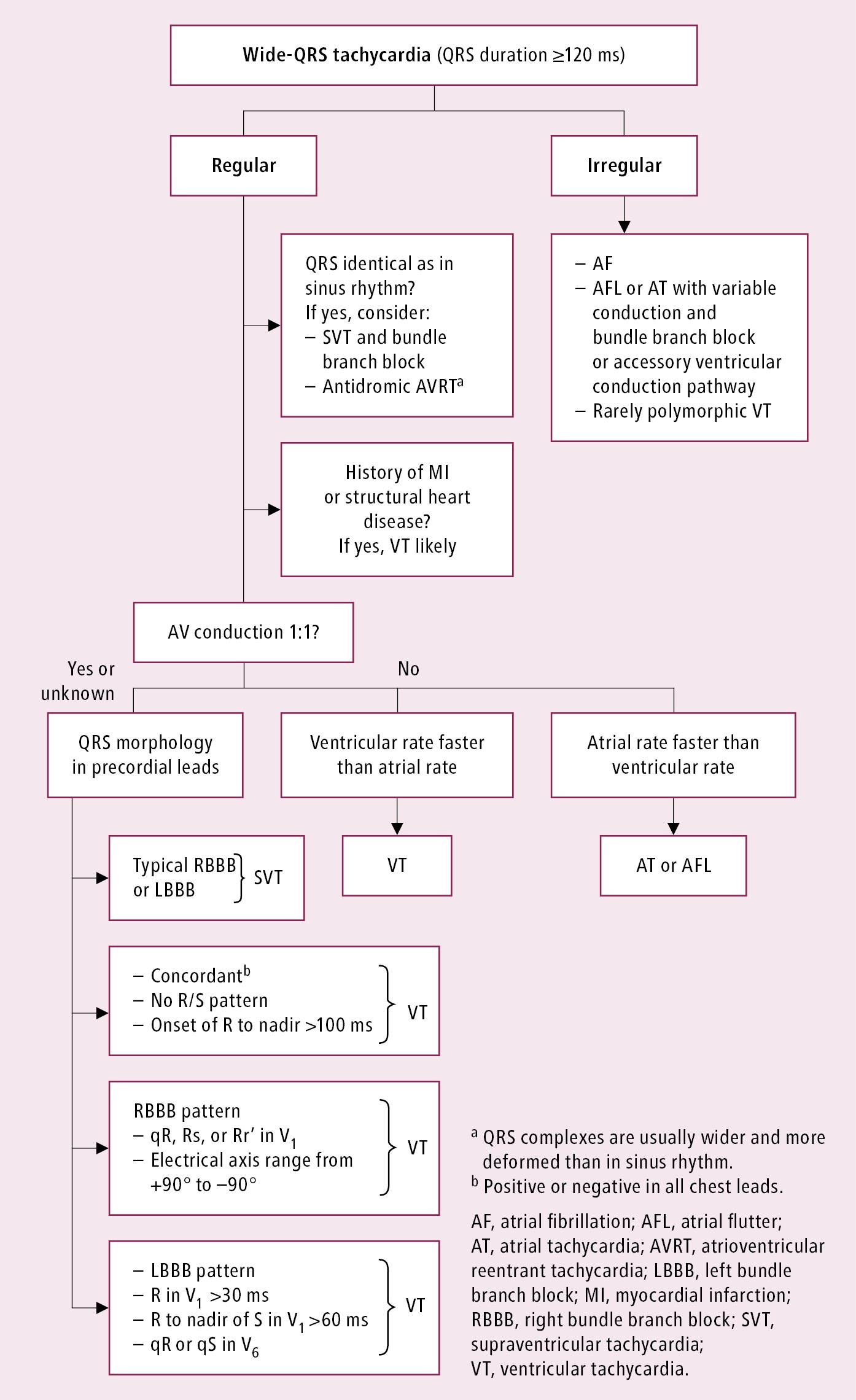

SVT: Figure 3.4-2. Narrow-QRS tachycardia: Figure 3.4-3. Wide-QRS tachycardia: Figure 3.4-4.

TreatmentTop

It is imperative to make the right diagnosis and to treat an identifiable cause or underlying condition. Treatment of specific arrhythmias may include the following:

1) Interventions aimed at increasing vagal tone (eg, carotid sinus massage, Valsalva maneuver). This at times can also aid in diagnosis.

2) Antiarrhythmic drugs: Different antiarrhythmic drugs can be used for different indications (Table 3.4-1, Table 3.4-2).

3) Electrical cardioversion and electrical defibrillation.

4) Insertion of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), a device that can detect tachyarrhythmia and terminate it in order to prevent sudden cardiac death (see Ventricular Arrhythmia Following Myocardial Infarction).

5) Catheter or surgical ablation: Catheter ablation involves destruction of the critical anatomical region of the cardiac tissue that is responsible for the generation or propagation of an arrhythmia. The procedure is performed percutaneously by introducing catheters into the heart via veins or arteries. Surgical ablation is done using thoracic surgery. Ablation can be applied for the treatment of AF, AFL, SVT, and VT.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Class |

Action |

Drugs | |

|

I |

Sodium channel blockade |

| |

|

Ia |

Moderate phase 0 depression, prolonging of action potential |

Quinidine, procainamide, disopyramide | |

|

Ib |

Minimal effect on phase 0, no change in duration of action potential |

Lidocaine, mexiletine | |

|

Ic |

Marked phase 0 depression, conduction slowing, little effect on repolarization |

Flecainide, propafenone | |

|

II |

Beta-adrenergic blockade |

Propranolol, metoprolol, atenolol, esmolol, bisoprolol | |

|

III |

Potassium channel blockade |

Amiodarone, sotalol, bretylium, ibutilide | |

|

IV |

Calcium channel blockade |

Verapamil, diltiazem | |

|

Agent |

Dosage |

Contraindications | |

|

Acutea |

Long term | ||

|

Adenosine (IV) |

6 mg in rapid IV injection followed by 12 or 18 mg after 1-2 min when necessary |

– |

Sinus node dysfunction, second-degree or third-degree AV block,b asthma. Use with caution in AF or AFL with suspected accessory pathway, prolonged QT, severe HF, or hypotension |

|

Amiodarone (IV, PO) |

5 mg/kg (most often 300 mg) IV over 15-30 min (infusions over 60-120 min are safer) followed by 900 mg/24 h (infusion); max, 1200 mg/d (sometimes up to 2000 mg/d) |

Loading dose: 200 mg (in selected cases 400 mg) tid for 7-14 days followed by 200 mg bid for 7-14 days Maintenance dose: usually 200 mg/d, in selected cases 100 or 300-400 mg/d |

Sinus node dysfunction, second-degree or third-degree AV block,b prolonged QT, drug hypersensitivity, thyrotoxicosis, liver disease, pregnancy, breastfeeding |

|

Digoxin (IV, PO) |

0.25 mg IV every 2 h; max total dose, 1.5 mg |

0.125-0.375 mg/d |

Bradycardia,b second-degree or third-degree AV block,b sick sinus syndrome,b carotid sinus syndrome, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with outflow tract obstruction, preexcitation syndromes, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, planned electrical cardioversion |

|

Diltiazem (PO) |

– |

90-240 mg/d |

HF, second-degree or third-degree AV blockb |

|

Dronedarone (PO) |

– |

400 mg bid |

Second-degree or third-degree AV block,b sick sinus syndrome,b HF or asymptomatic LV dysfunction, permanent AF |

|

Flecainide (IV, PO) |

2 mg/kg IV bolus (max, 150 mg) PO: 300 mg (“pill in the pocket” for acute AF) |

50-150 mg PO bid |

Structural heart disease (in particular heart failure), CAD, sinus node dysfunction, second-degree or third-degree AV blockb |

|

Lidocaine (IV) |

50 mg IV over 2 min; can be repeated every 5 min up to total of 200 mg followed by infusion of 1-4 mg/min; dose should be tapered off |

– |

Hypersensitivity to local anesthetic drugs |

|

Metoprolol (IV, PO) |

5 mg IV every 5-10 min up to total of 15 mg |

50-200 mg/d |

Second-degree or third-degree AV block,b symptomatic bradycardia, symptomatic hypotension, sick sinus syndrome, decompensated HF, asthma |

|

Procainamide (IV) |

Loading dose: 100-200 mg/dose or 15-18 mg/kg; do not exceed 50 mg/min; can be repeated every 5 min if required; do not exceed 1 g Maintenance dose: 1-4 mg/min IV infusion |

– |

Sinus node dysfunction, second-degree or third-degree AV blockb, prolonged QT, drug hypersensitivity |

|

Propranolol (IV, PO) |

1-5 mg IV (in selected cases 10 mg); administer 1 mg over 1 min |

20-40 mg every 8 h |

Second-degree or third-degree AV block,b symptomatic bradycardia, symptomatic hypotension, sick sinus syndrome, decompensated HF, asthma |

|

Propafenone (IV, PO) |

1-2 mg/kg IV over 5 min PO: 600 mg (“pill in the pocket” for AF) |

150-300 mg every 8-12 h |

Structural heart disease (in particular HF), CAD, sinus node dysfunction, second-degree or third-degree AV blockb |

|

Verapamil (IV, PO) |

5-10 mg IV over 1-2 min |

120-360 mg/d |

HF, second-degree or third-degree AV blockb |

|

a Monitor electrocardiography and blood pressure. b In patients without an implanted pacemaker. | |||

|

AF, atrial fibrillation; AFL, atrial flutter; AV, atrioventricular; bid, 2 times a day; CAD, coronary artery disease; HF, heart failure; IV, intravenous; LV, left ventricle; PO, oral; tid, 3 times a day; VT, ventricular tachycardia. | |||

Figure 3.4-1. Simplified categorization of arrhythmias.

Figure 3.4-2. Differential diagnosis of supraventricular tachycardia based on the relationship of P waves and QRS complexes.

Figure 3.4-3. Differential diagnosis of narrow-QRS tachycardia. Adapted from guidelines by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

Figure 3.4-4. Differential diagnosis of wide-QRS tachycardia. Adapted from guidelines by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.