Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 14;42(35):3427-3520. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab364. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2022 Feb 16;: PMID: 34455430.

Writing Committee Members, Kusumoto FM, Schoenfeld MH, Barrett C, et al. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline on the evaluation and management of patients with bradycardia and cardiac conduction delay: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2019 Sep;16(9):e128-e226. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.10.037. Epub 2018 Nov 6. PMID: 30412778.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Sinus node dysfunction refers to pathologies resulting in inappropriately low heart rates that are insufficient for the current physiologic needs and thus cause clinical symptoms.

Disorders of sinus node automaticity and conduction may be intermittent or persistent; persistent disorders are referred to as sick sinus syndrome (SSS). In patients with bradycardia following episodes of supraventricular tachycardia (most commonly atrial fibrillation [AF], known as postconversion pauses), tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome is diagnosed.

Causes: Ischemic heart disease, systemic connective tissue disease, postoperative complications, idiopathic degeneration related to aging, functional sinus node dysfunction (due to vagal reflexes, disturbances in serum electrolyte levels [hypokalemia or hyperkalemia], metabolic abnormalities [hypothyroidism, hypothermia, anorexia nervosa], neurologic conditions [elevated intracranial pressure, central nervous system tumors], obstructive sleep apnea), drugs (beta-blockers, diltiazem or verapamil, digitalis, class I antiarrhythmic drugs [see Table 3.4-1], amiodarone, lithium).

Sinus node dysfunction is frequently accompanied by loss of a normal chronotropic response to exercise, that is, inability to achieve 85% of the maximum heart rate predicted for age, and in 20% to 30% of patients, by atrioventricular or intraventricular conduction disturbances.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

Signs and symptoms: see Disorders of Automaticity and Conduction.

Sinus node dysfunction may be transient/intermittent (eg, following myocardial infarction, drug induced) or persistent. Prognosis primarily depends on the underlying condition, concomitant tachyarrhythmias, length of the sinus pauses, and risk of thromboembolic complications (stroke or peripheral embolism) if the patient has concomitant AF (see Atrial Fibrillation).

DiagnosisTop

Electrocardiography (ECG):

1) Sinus bradycardia: Sinus rhythm with heart rates <50 beats/min when awake.

2) Sinus pause: No sinus P wave in a period longer than a PP interval of the baseline rhythm. The pause is not a multiplication of the normal PP intervals.

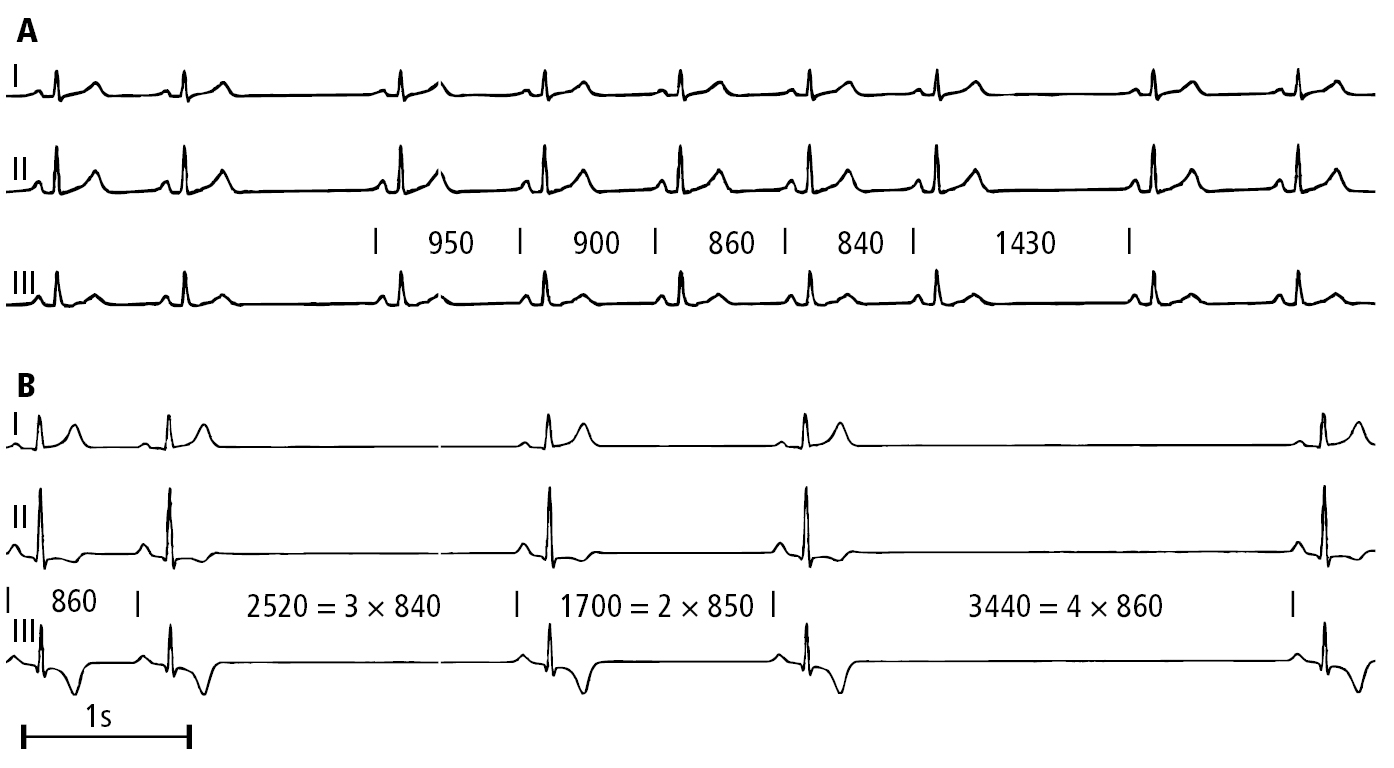

3) Sinoatrial (SA) block (Figure 3.2-1): We use a similar denomination as the one used for AV blocks. Some of the sinus impulses are “blocked” before they can leave the SA node:

a) Mobitz type I (Wenckebach): A progressive increase in the SA conduction time until one beat is blocked, which is reflected in a progressive shortening of the PP interval followed by an absent P wave-QRS complex.

b) Mobitz type II: Intermittent P waves “drop out” of the rhythm, while subsequent P waves arrive “on time.” The resulting pause is a multiplication of baseline sinus rhythm.

c) Third-degree SA block: Complete absence of P waves.

4) Tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome: Commonly seen as a prolonged postconversion pause after an episode of AF transitioning to sinus rhythm.

The diagnosis of SSS requires documented symptoms during an episode of bradycardia <40 beats/min or pauses >3 seconds during daytime. Prolonged Holter monitoring is the best diagnostic tool. Atrial flutter and AF may mask sinus node dysfunction, which is revealed only after cardioversion.

Other causes of syncope (see Syncope).

TreatmentTop

1. Management of symptomatic bradycardia: see Figure 3.2-4.

2. Long-term management:

1) In the case of patients involved in sports, stop training, perform a follow-up assessment, and decide about the possible continuation of training based on the results.

2) Optimize treatment of the underlying condition and discontinue drugs causing bradycardia.

3) Theophylline may be useful in some patients but it is rarely suitable for long-term therapy and not used in Canada.

4) Implantation of a cardiac pacemaker (see Disorders of Automaticity and Conduction) in patients with persistent bradycardia causing unequivocally documented symptoms or with intermittent bradycardia caused by sinus pauses or SA block. The recommended first-line mode of stimulation is DDDR (or DDD in patients with persistent bradycardia and no chronotropic incompetence) with delayed ventricular stimulation.

FiguresTop

Figure 3.2-1. Electrocardiography (ECG) of a patient with sinus node dysfunction: A, second-degree sinoatrial block, Mobitz type I (Wenckebach); B, advanced second-degree sinoatrial block. Figure courtesy of Dr Andrzej Stanke.