Lindson N, Theodoulou A, Ordóñez-Mena JM, et al. Pharmacological and electronic cigarette interventions for smoking cessation in adults: component network meta-analyses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;9(9):CD015226. Published 2023 Sep 12. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD015226.pub2. PMID: 37696529; PMCID: PMC10495240.

Galiatsatos P, Garfield J, Melzer AC, et al. Summary for Clinicians: An ATS Clinical Practice Guideline for Initiating Pharmacologic Treatment in Tobacco-Dependent Adults. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(2):187-190. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202008-971CME. PMID: 33052710.

Sadek J, Moloo H, Belanger P, et al. Implementation of a systematic tobacco treatment protocol in a surgical outpatient setting: a feasibility study. Can J Surg. 2021;64(1):E51-E58. Published 2021 Feb 3. doi:10.1503/cjs.009919. PMID: 33533579; PMCID: PMC7955818.

Leone FT, Zhang Y, Evers-Casey S, et al. Initiating Pharmacologic Treatment in Tobacco-Dependent Adults. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):e5-e31. doi:10.1164/rccm.202005-1982ST. PMID: 32663106; PMCID: PMC7365361.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Reports and Publications. Reviewed January 23, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/tobacco/index.html

Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD000146. Published 2018 May 31. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub5. PMID: 29852054; PMCID: PMC6353172.

Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral and Pharmacotherapy Interventions for Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Oct 20;163(8):622-34. doi: 10.7326/M15-2023. PMID: 26389730.

Leone FT, Carlsen KH, Folan P, et al; ATS Tobacco Action Committee; American Thoracic Society. An Official American Thoracic Society Research Statement: Current Understanding and Future Research Needs in Tobacco Control and Treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Aug 1;192(3):e22-41. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1081ST. PMID: 26230245.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2014. PMID: 24455788.

Epidemiology and Risk FactorsTop

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), nicotine dependence and tobacco use are the leading causes of preventable death and disease in the world, resulting in almost 6 million deaths each year. Approximately half of smokers die from a smoking-related cause. Although the prevalence of smoking in high-income countries is decreasing, the vast majority of smokers live in middle- or low-income countries where, depending on the country, up to 50% of men and 10% of women smoke daily.Evidence 1Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due indirectness. Hosseinpoor AR, Parker LA, Tursan d’Espaignet E, Chatterji S. Socioeconomic inequality in smoking in low-income and middle-income countries: results from the World Health Survey. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42843. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042843. PMID: 22952617; PMCID: PMC343063.

Health hazards of tobacco: Smoking reduces life expectancy by an average of 10 years.Evidence 2High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004 Jun 26;328(7455):1519. PMID: 15213107; PMCID: PMC437139. It is a major cause of cancer (Table 17.12-1), cardiovascular diseases, and respiratory diseases. Second-hand smoke has also been shown to result in premature death and cancer and to have cardiovascular, respiratory, pediatric, and reproductive health effects. There is a clear dose-response relationship between smoking and the risk of lung cancer.Evidence 3High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Carter BD, Abnet CC, Feskanich D, et al. Smoking and mortality--beyond established causes. N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 12;372(7):631-40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1407211. PMID: 25671255. Smoking triples the odds of cardiovascular disease, with the risk increasing linearly with the number of cigarettes smoked.Evidence 4High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Teo KK, Ounpuu S, Hawken S, et al; INTERHEART Study Investigators. Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction in 52 countries in the INTERHEART study: a case-control study. Lancet. 2006 Aug 19;368(9536):647-58. PMID: 16920470.

DiagnosisTop

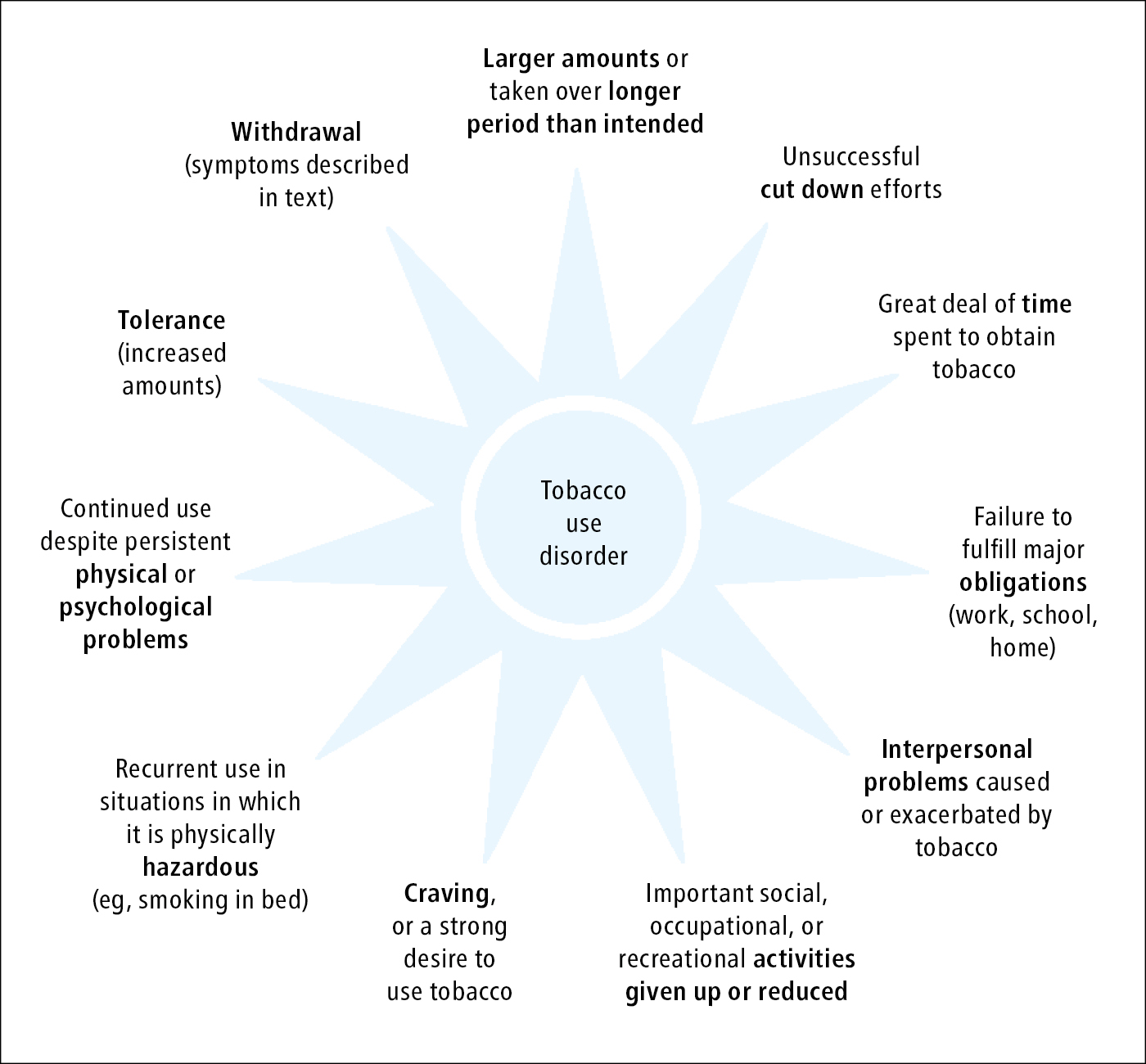

Nicotine is the main substance leading to physiologic dependence in smokers. Nicotine dependence has been classified by the WHO as a disorder caused by nicotine addiction (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] code F17). The fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) has changed the terminology for tobacco use disorder and defines it as the presence of 2 out of 11 criteria (Figure 17.12-1) within the past year. Practically, nicotine dependence is defined as the use of nicotine in any form, which results in physiologic and psychologic dependence, making it difficult to quit due to nicotine withdrawal symptoms.

The severity of dependence may be judged using a combination of several questions (Table 17.12-2).

Signs and symptoms of nicotine withdrawal (selected, in isolation neither sensitive nor specific):

1) Symptoms: Craving for nicotine, obsessive thoughts about smoking, anxiety, tension, difficulty in relaxing, nervousness (irritability or aggression), discomfort, frustration, depression or depressed mood, impaired concentration, sleep disorders, and increased appetite.

2) Signs: Bradycardia, hypotension, decreased blood levels of cortisol and catecholamines, memory impairment, selective attention disturbances, weight gain.

The signs and symptoms are most pronounced within 4 weeks of ceasing to smoke, and then gradually disappear over the next 6 to 12 weeks. However, the urge to smoke frequently occurs even months or years after quitting and may lead to relapse.

Treatment (Smoking Cessation)Top

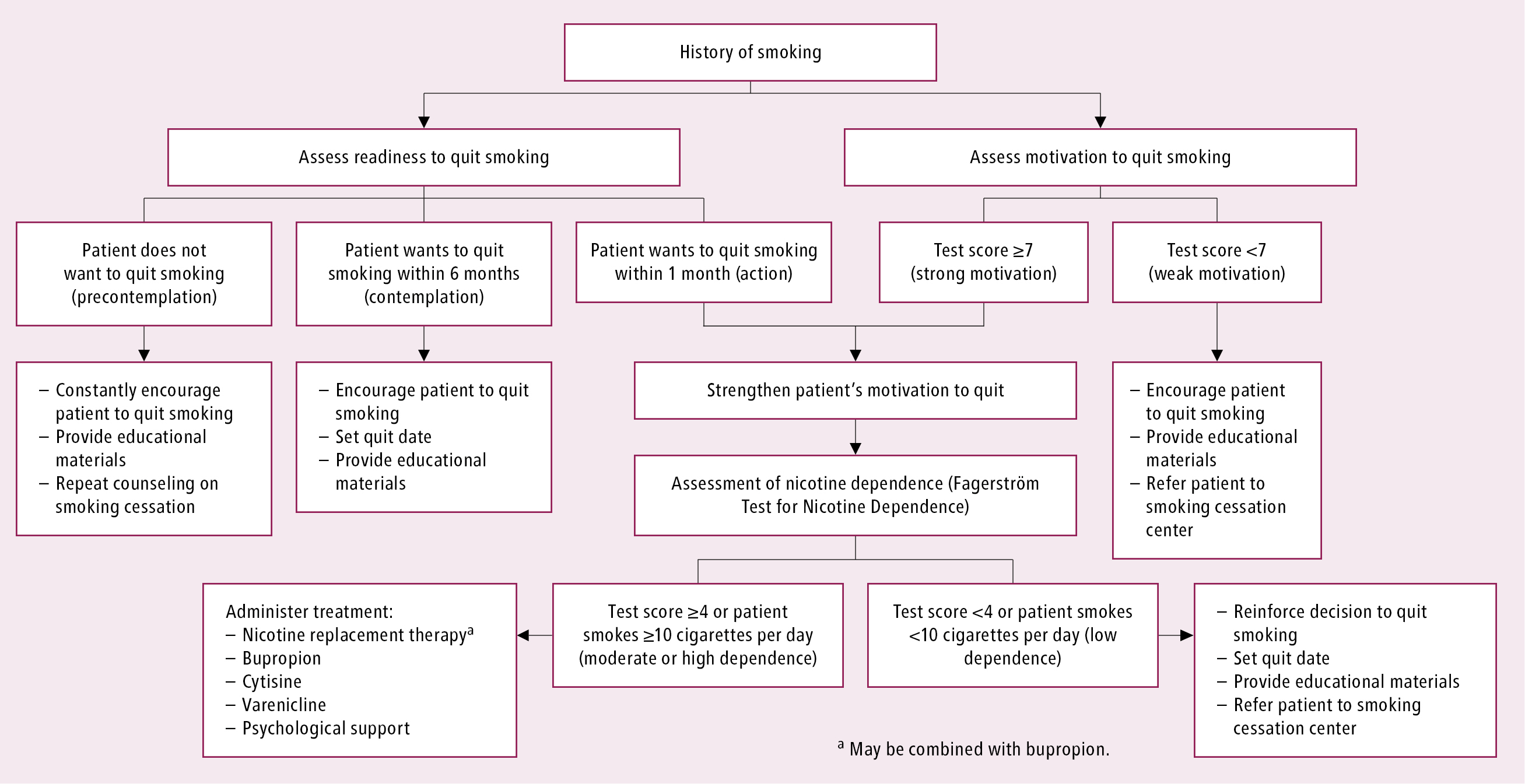

Patients can stop smoking by themselves, but evidence supports psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions to assist cessation. Assessment of tobacco use is an iterative process and can be brief and pragmatic (Figure 17.12-2).

1. When talking with the patient, clearly emphasize the most important health consequences of smoking, highlight the benefits of smoking cessation that are relevant to the patient (Table 17.12-3), and discuss potential difficulties in quitting and methods of coping with them (eg, discuss the symptoms and management of withdrawal).

2. Interventions should be positive and nonjudgmental.

3. Weight gain may be controlled by recommending adequate physical activity and a healthy diet. Exercise can also help control cravings. The use of medications recommended for nicotine addiction in patients who have quit smoking delays but does not prevent weight gain. New methods of weight control could be considered: see Obesity.

4. Treatment modalities are selected on the basis of the patient’s readiness to cease smoking, individual characteristics and preferences of the patient, amount of time dedicated to the patient, level of nicotine dependence, qualifications of the clinician, and cost of the interventions.

5 A’s Tobacco Cessation Strategy

1. Ask the patient about their smoking status (current, former, never) and record it in the medical chart.

2. Advise the patient to quit smoking. Strengthen their motivation by referring to personal health, the health of household members, being a role model for smoking family members or colleagues, the economic cost of smoking, esthetic concerns, and self-control.Evidence 5Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, Sanchez G, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 May 31;(5):CD000165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub4. Review. PMID: 23728631.

3. Assess the patient’s motivation to quit. This could be done in several ways, for instance, by following the factors below over time on a scale from 1 to 10:

1) How important it is for the patient to quit at this time.

2) How confident they are that it would be possible to quit at this time.

3) How ready they are to quit.

Another way is to use the toolkit recommended by the WHO to deliver brief interventions in primary care. Here, the readiness to quit can be assessed using 2 questions:

1) Would you like to be a non–tobacco user?

2) Do you think you have a chance of quitting successfully?

If responding with “no” to any of the questions or “unsure” to the first question, the patient is not ready to quit and needs additional interventions aimed at increasing their motivation to quit. In such patients, a brief motivational intervention called the 5 R’s can be used. The 5 elements addressed in this intervention are relevance (how quitting smoking is personally relevant), risks (what are the negative consequences of smoking relevant for the patient), rewards (what are the benefits of quitting smoking), roadblocks (what are the barriers to quitting and how they can be solved), and repetition (should be repeated at every visit of a patient not ready to quit).

Lastly, the readiness to quit may be more formally assessed by asking explicit questions (responding with “yes” indicates readiness, with ≥7 “yeses” suggesting a strong motivation/higher chance of quitting: Figure 17.12-2):

1) Do you want to quit smoking?

2) Do you want to quit because it is important to you personally rather than to other people?

3) Have you tried to quit before?

4) Do you recognize situations that lead you to smoke?

5) Do you know why you smoke?

6) Can you count on help from family and/or friends?

7) Are other members of your family nonsmokers?

8) Is your workplace smoke free?

9) Are you satisfied with your work and lifestyle?

10) Do you know where to seek help if you have difficulties quitting?

11) Do you recognize any difficult situations that you may experience when quitting/abstaining from smoking?

12) Do you cope well in crisis situations?

4. Assist the patient in quitting:

1) Make a quit plan. Start off by setting a quit date. In some cases the patient may prefer gradual reduction. Support them by setting reduction targets and dates as agreeable to the patient.Evidence 6Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision. Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P, Hughes JR. Reduction versus abrupt cessation in smokers who want to quit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Nov 14;11:CD008033. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008033.pub3. Review. PMID: 23152252.

2) Use motivational interviewing (motivationalinterviewing.org).Evidence 7Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to potential reporting, publication bias, and moderate heterogeneity. Lindson-Hawley N, Thompson TP, Begh R. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Mar 2;(3):CD006936. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006936.pub3. Review. PMID: 25726920.

3) Provide the patient with a combination of educational materials (pamphlets or booklets, websites, lectures, support groups, smartphone applications, and access to a quit line). Referral to a specialized smoking cessation program should be considered.

4) Use multiple (≥4) brief counseling interventions (1-3 minutes) with occasional intensive interventions whenever possible. There is a dose-response effect for the number and length of counseling sessions.Evidence 8Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Stead LF, Lancaster T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Oct 17;10:CD008286. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008286.pub2. Review. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD008286. PMID: 23076944. Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Lancaster T. Additional behavioural support as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Oct 12;(10):CD009670. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009670.pub3. Review. PMID: 26457723.

5) Combine counseling and pharmacologic treatment, as they are more effective when used together.Evidence 9Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Stead LF, Lancaster T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Oct 17;10:CD008286. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008286.pub2. Review. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD008286. PMID: 23076944. Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Lancaster T. Additional behavioural support as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Oct 12;(10):CD009670. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009670.pub3. Review. PMID: 26457723.

6) Suggest physical activityEvidence 10Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to high risk of bias, high level of clinical heterogeneity, and inadequate sample size. Ussher MH, Taylor AH, Faulkner GE. Exercise interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Aug 29;(8):CD002295. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002295.pub5. Review. PMID: 25170798. and a diet with ample fruit and fluids to stay committed to the decision to quit and mitigate the risk of weight gain.

7) Remove triggers. Advise the patient to get rid of cigarettes at home and to avoid smokers and situations that may trigger an urge to smoke.

8) Be patient. Warn the patient that the first few weeks will be challenging.

5. Arrange follow-up visits in person or via telephone calls to assess the quit plan. The first contact should be arranged within 1 week following the established quit date, the second one within the following month, and subsequent contacts as needed. At each visit:

1) If the attempt was successful, congratulate the patient and emphasize the need for total abstinence from smoking.

2) If the attempt was unsuccessful, encourage the patient by saying that relapses are common and even a short break from smoking is beneficial. Discuss the reasons for failure and prescribe medications or increase the dose of agents used in nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).

3) Refer the patients to a smoking cessation clinic if available and not done yet. Consider using an opt-out approach (systematically refer all patients for a follow-up unless they actively refuse) as opposed to an opt-in approach (only the patients who explicitly request or accept the referral are sent for a follow-up).

Formulations, dosage, and principles of NRT: Table 17.12-4.

Dosage of nonnicotine agents used in the treatment of nicotine addiction: Table 17.12-5.

Smokers willing to quit should be offered pharmacologic therapy to reduce cravings and maximize their chances of prolonged abstinence. Pharmacotherapy interventions, including NRTs, bupropion (sustained release), varenicline, or cytisine—ideally in association with behavioral counseling—can increase the rate of tobacco abstinence in comparison with either used alone and are recommended. It can be estimated that the odds of successful quitting in comparison with placebo are almost doubled by a single form of NRT and bupropion, and increased even more by varenicline and cytisine. Of note, although the probability of quitting is increased by all those interventions, the success rate for any given attempt is still markedly <50%. The efficacy of combined forms of NRT (patches, gums, inhalers, lozenges) is likely comparable with varenicline. We therefore strongly recommend that pharmacotherapy should be offered in motivated patients who need such support and that a number of alternatives should be suggested.Evidence 11Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Lindson N, Theodoulou A, Ordóñez-Mena JM, et al. Pharmacological and electronic cigarette interventions for smoking cessation in adults: component network meta-analyses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;9(9):CD015226. Published 2023 Sep 12. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD015226.pub2. PMID: 37696529; PMCID: PMC10495240. Stead LF, Lancaster T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Oct 17;10:CD008286. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008286.pub2. Review. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD008286. PMID: 23076944. Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Lancaster T. Additional behavioural support as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Oct 12;(10):CD009670. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009670.pub3. Review. PMID: 26457723.

1. NRTs are recommended for smoking cessation.Evidence 12Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Lindson N, Theodoulou A, Ordóñez-Mena JM, et al. Pharmacological and electronic cigarette interventions for smoking cessation in adults: component network meta-analyses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;9(9):CD015226. Published 2023 Sep 12. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD015226.pub2. PMID: 37696529; PMCID: PMC10495240. Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD000146. Published 2018 May 31. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub5. PMID: 29852054; PMCID: PMC6353172. Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, et al. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Nov 14;11:CD000146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub4. Review. PMID: 23152200. Replacement therapies reduce cravings induced by abstinence or reduction and increase the rate of abstinence across different populations (patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, patients with psychiatric disorders, African Americans). Combined use of short-acting (gums, lozenges, inhalers) and long-acting (patches) NRTs is more effective than monotherapy.Evidence 13High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Theodoulou A, Chepkin SC, Ye W, et al. Different doses, durations and modes of delivery of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;6(6):CD013308. Published 2023 Jun 19. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013308.pub2. PMID: 37335995; PMCID: PMC10278922. Contrary to the popular belief, smoking while on NRT does not appear to be harmful, and NRT can be used as part of the “reduce-to-quit” strategy. We consider NRT to be safe in patients post acute coronary syndromes (ACSs) and certainly a safer alternative to cigarettes: see Special Considerations.

Replacement therapy should be matched to current nicotine consumption, considering that 1 cigarette equals 1 to 2 mg of nicotine. The dose can then be adjusted according to the frequency of cravings or adverse effects from nicotine overdose: hiccups, xerostomia, dyspepsia, nausea, heartburn, tachycardia, or sleep disorders. Temporomandibular articular pain from gum chewing can be relieved by intermittent chewing and parking the gum between the jaw and the cheek. Skin reaction from the patch may occur and tends to attenuate after a few weeks of usage.

2. Sustained-release bupropion reduces nicotine reinforcement and cravings by blocking reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine. We suggest it in smokers in the preparation phase with a set quit date.Evidence 14Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Hughes JR, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, Cahill K, Lancaster T. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jan 8;(1):CD000031. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub4. Review. PMID: 24402784. It may be preferred in patients with depressive symptoms or patients worried about weight gain. The primary contraindications to the use of bupropion are a past history of seizures of any etiology, head trauma, and eating disorders. The rate of de novo seizures is low (<0.5%) and generally associated with doses >450 mg. Alcohol can be consumed in moderate amounts and should not be discontinued abruptly, as this may increase the risk of withdrawal-related seizures. The other adverse reactions include insomnia, agitation, dry mouth, changes in behavior, hostility, agitation, depressed mood, suicidal ideations, and suicidal attempts.

3. Varenicline is a synthetic nicotinic receptor partial agonist that binds to receptors with a greater affinity than nicotine. As with bupropion, we suggest it be used in the preparation phase in motivated patients with a set quit date or in patients who have failed NRT alone.Evidence 15Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, et al; Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006 Jul 5;296(1):56-63. Erratum in: JAMA. 2006 Sep 20;296(11):1355. PMID: 16820547. Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, et al; Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006 Jul 5;296(1):47-55. PMID: 16820546. Tonstad S, Tønnesen P, Hajek P, Williams KE, Billing CB, Reeves KR; Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group. Effect of maintenance therapy with varenicline on smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006 Jul 5;296(1):64-71. PMID: 16820548. Cahill K, Lindson-Hawley N, Thomas KH, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 9;(5):CD006103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub7. Review. PMID: 27158893. Contraindications include allergy to the medication or its components. Precautions must be taken if considering use in patients who are pregnant or have end-stage renal failure. Although major studies have not demonstrated an increase in neuropsychiatric adverse events, mood disorders are more prevalent in smokers, which is why screening for these is recommended prior to and during treatment. The most common adverse effects of varenicline include moderate nausea that resolves in the course of treatment, abnormal dreams, insomnia, and headache.

4. Cytisine is a natural alkaloid and a nicotinic receptor partial agonist with a documented efficacy superior to NRT in healthy individuals. It was approved as a natural health product by Health Canada in 2017. It is only available in selected pharmacies, which limits access, and the current dosing schedule is complex, which is a barrier for compliance. However, this may change soon, as a recent 2023 randomized controlled trial of >800 patients demonstrated efficacy and tolerability of a simplified dosing regimen of 3 mg given orally tid for up to 12 weeks.Evidence 16Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision. Rigotti NA, Benowitz NL, Prochaska J, et al. Cytisinicline for Smoking Cessation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023;330(2):152-160. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.10042. PMID: 37432430; PMCID: PMC10336611. Lindson N, Theodoulou A, Ordóñez-Mena JM, et al. Pharmacological and electronic cigarette interventions for smoking cessation in adults: component network meta-analyses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;9(9):CD015226. Published 2023 Sep 12. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD015226.pub2. PMID: 37696529; PMCID: PMC10495240. Walker N, Howe C, Glover M, et al. Cytisine versus nicotine for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 18;371(25):2353-62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407764. PMID: 25517706. Cahill K, Lindson-Hawley N, Thomas KH, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 9;(5):CD006103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub7. Review. PMID: 27158893. Contraindications include hypersensitivity to cytisine, hypertension, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. Use cytisine with caution in patients with advanced atherosclerosis or active peptic ulcer disease. Adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, pyrosis, xerostomia, pupil dilation, tachycardia, hypertension, fatigue, and malaise.

5. Electronic cigarettes or electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDSs) have provided smokers with a new and attractive option to manage nicotine withdrawal and assist smoking cessation. Recent studies have shown that nicotine e-cigarettes increase smoking cessation among current smokers interested in quitting when compared with NRT or behavioral counseling only.Evidence 17Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity (variability in devices used) and imprecision (small number of events). Hartmann-Boyce J, McRobbie H, Butler AR, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;9(9):CD010216. Published 2021 Sep 14. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub6. PMID: 34519354; PMCID: PMC8438601. Lam C, West A. Are electronic nicotine delivery systems an effective smoking cessation tool? Can J Respir Ther. 2015 Fall;51(4):93-8. Review. PMID: 26566380; PMCID: PMC4631136. Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016 Feb;4(2):116-28. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00521-4. Review. PMID: 26776875; PMCID: PMC4752870. However, other studies have shown that co-use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes may increase nicotine dependence and cigarette consumption. Long-term health consequences are not fully known. Given the above, e-cigarettes are not recommended as first-line cessation aids.

Special ConsiderationsTop

NRT and varenicline have been studied in patients following ACS who were not found to have an increased risk of major adverse events.Evidence 18Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the risk of bias, imprecision, and observational nature of the data. Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD000146. Published 2018 May 31. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub5. PMID: 29852054; PMCID: PMC6353172. Concerns have been raised about the physiologic impact of nicotine, such as tachycardia and arrhythmia, on patients post ACS, but this has not resulted in an increased risk of major adverse cardiac events. Patients who smoke are at risk not only of the adverse events associated with nicotine but also of the harmful effects of smoking. Accordingly, smoking cessation is priority.

Cigarette smoking during pregnancy and exposure to second-hand smoke in early infancy are associated with multiple negative effects including low birth weight, increased preterm labor and pregnancy loss, sudden infant death syndrome, and childhood respiratory illnesses. Thus, all pregnant patients should be advised to stop smoking and make their environment smoke free.Evidence 19Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, the risk of bias, and indirectness. Coleman T, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, Cooper SE, Leonardi-Bee J. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(12):CD010078. Published 2015 Dec 22. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010078.pub2. PMID: 26690977. Because of conflicting evidence of congenital defects associated with NRT, counseling should be considered the first line of therapy for smoking cessation in pregnant patients. If continuing to smoke, short-term NRT with gums or lozenges would be preferred to manage acute withdrawal symptoms rather than continuous transcutaneous nicotine. However, as ongoing smoking is more harmful to the pregnant patient and the fetus, such patients should be followed closely to support them in quitting by any means that may be necessary.

Smoking is a risk factor for increased perioperative complications, with the evidence pointing towards improved outcomes with smoking cessation. Most interventions aim at discontinuation of smoking 4 to 6 weeks before surgery, but even a shorter time of abstinence may be beneficial.Evidence 20Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to the heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes. Thomsen T, Villebro N, Møller AM. Interventions for preoperative smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(3):CD002294. Published 2014 Mar 27. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002294.pub4. PMID: 24671929; PMCID: PMC7138216. Sadek J, Moloo H, Belanger P, et al. Implementation of a systematic tobacco treatment protocol in a surgical outpatient setting: a feasibility study. Can J Surg. 2021;64(1):E51-E58. Published 2021 Feb 3. doi:10.1503/cjs.009919. PMID: 33533579; PMCID: PMC7955818.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Cancer site |

Average relative risk |

|

Lung |

15.0-30.0 |

|

Urinary tract |

3.0 |

|

Upper aerodigestive tract (larynx,a oral cavity, oropharynx and hypopharynx,a esophagus) |

2.0-10.0 |

|

Esophagus (adenocarcinoma) |

1.5-2.5 |

|

Pancreas |

2.0-4.0 |

|

Nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses |

1.5-2.5 |

|

Stomach |

1.5-2.0 |

|

Kidney |

1.5-2.0 |

|

Uterine cervix |

1.5-2.5 |

|

Myeloid leukemia |

1.5-2.0 |

|

a Synergistic interaction with alcohol use. | |

|

Adapted from J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(2):99-106. | |

|

Questions |

Answers |

Score |

|

1. How soon after you wake up do you smoke your first cigarette? |

Within 5 minutes 6-30 minutes 31-60 minutes After 60 minutes |

3 2 1 0 |

|

2. Do you find it difficult to refrain from smoking in places where smoking is forbidden (eg, in church, at the library, in cinema)? |

Yes No |

1 0 |

|

3. Which cigarette would you hate most to give up? |

The first one in the morning All others |

1 0 |

|

4. How many cigarettes a day do you smoke? |

≤10 11-20 21-30 ≥31 |

0 1 2 3 |

|

5. Do you smoke more frequently during the first hours after waking than during the rest of the day? |

Yes No |

1 0 |

|

6. Do you smoke if you are so ill that you are in bed most of the day? |

Yes No |

1 0 |

|

|

Total |

|

|

Severity of nicotine dependence |

Score 0-3: Low dependence 4-6: Moderate dependence 7-10: High dependence | |

|

Source: Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119-27. | ||

|

Time after quitting |

Effect |

|

20 min |

Heart rate and blood pressure drop |

|

12 h |

Blood carbon monoxide level drops to normal |

|

2 weeks to 3 months |

Circulation improves and lung function increases |

|

1-9 months |

Coughing and shortness of breath decrease. Cilia start to regain normal function in the lungs |

|

1 year |

Excess risk of coronary artery disease is half that of a continuing smoker |

|

5 years |

Risk of cancer of the mouth, throat, esophagus, and bladder is cut in half. Cervical cancer risk falls to that of a nonsmoker’s. Stroke risk can fall to that of a nonsmoker’s after 2-5 years |

|

10 years |

Risk of dying from lung cancer is about half that of a person who is still smoking. Risk of cancer of the larynx and pancreas decreases |

|

15 years |

Risk of coronary artery disease is that of a nonsmoker |

|

Formulation |

Dosage |

Comments |

|

Short-acting Nicotine gum: 2 mg and 4 mg Nicotine lozenges: 1.5 mg, 2 mg, 4 mg Nicotine inhaler: 10 mg Nicotine spray: 1 mg/spray |

The long-acting nicotine replacement should be adjusted to current nicotine intake and combined with short-acting replacement used as needed to reduce cravings 1 cigarette = 1-2 mg of nicotine 21 mg for 6 weeks, 14 mg for 2 weeks, 7 mg for 2 weeks. Adjust for overdose symptoms or cravings |

|

|

Long-acting Nicotine 24-h transdermal system: 7 mg, 14 mg, 21 mg Nicotine 16-h transdermal system: 10 mg, 15 mg, 25 mg |

16-h patch can be used during daytime to minimize vivid dreams or insomnia |

|

Agent |

Dosage | |

|

Initial treatment |

Maintenance treatment | |

|

Sustained-release bupropion tablets 150 mg |

Treatment should be started 1-2 weeks before the scheduled quit date. On days 1-3 use 1 tablet (150 mg) in the morning; from day 4 for 7-12 weeks from the date of smoking cessation use 150 mg bid |

Treatment can be prolonged to 6 months according to patient preferences |

|

Cytisine tablets 1.5 mg

|

Treatment should be started 1-5 days before the scheduled quit date Days 1-3: Use 1 tablet (1.5 mg) every 2 h (6 × day) Days 4-12: 1 tablet every 2.5 h (5 × day) Days 13-16: 1 tablet every 3 h (4 × day) Days 17-20: 1 tablet every 5 h (3 × day) Days 20-25: 1 to 2 tablets a day |

– |

|

Varenicline film-coated tablets 0.5 mg, 1 mg |

Treatment should be started 1-2 weeks before the scheduled quit date. On days 1-3 use 1 tablet (0.5 mg) once daily; days 4-7, 1 tablet (0.5 mg) bid; from day 8 for the next 11 weeks, 1 mg bid |

In patients who quit smoking in the course of 12-week treatment you may consider using 1 mg bid for the next 12 weeks |

|

bid, 2 times a day. | ||

Figure 17.12-1. Criteria defining tobacco use disorder.

Figure 17.12-2. Smoking cessation algorithm (Fagerström test: Table 2; test of motivation: 5 A’s Tobacco Cessation Strategy).