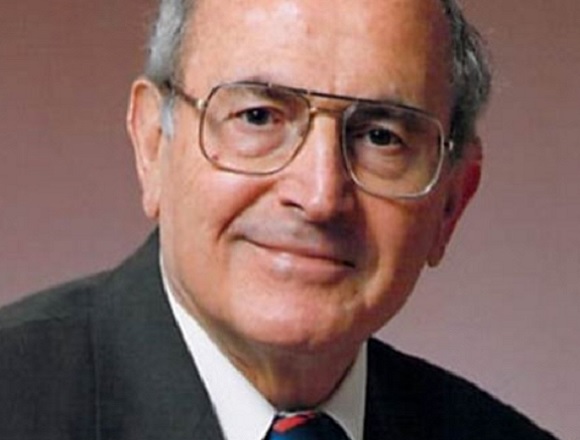

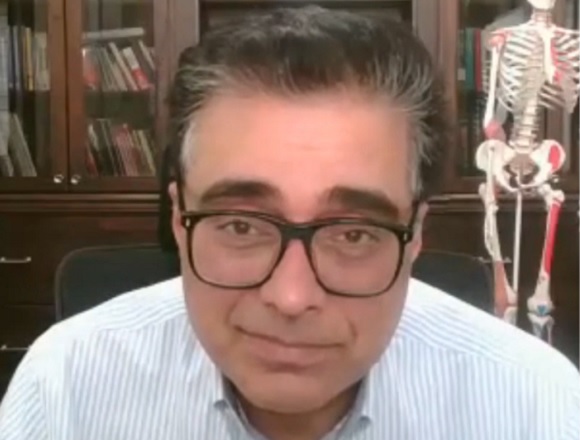

Aliya Khan, MD, is a clinical professor of medicine in the Divisions of Endocrinology and Metabolism and Geriatrics at McMaster University, director of the Calcium Disorders Clinic at McMaster University Medical Centre, and director of the Fellowship Program in Metabolic Bone Disease at McMaster University. In this episode of McMaster Perspective Dr Khan joins Dr Roman Jaeschke, MD, MSc, critical care physician and methodologist, to talk about the etiology, diagnosis, and management of hypoparathyroidism.

References

2. Khan AA, Bilezikian JP, Brandi ML, et al. The Second International Workshop on the Evaluation and Management of Hypoparathyroidism. J Bone Miner Res. 2022 Dec;37(12):2566-2567. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4671. Epub 2022 Nov 14. PMID: 36375811.

3. Mannstadt M, Cianferotti L, Gafni RI, et al. Hypoparathyroidism: Genetics and Diagnosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2022 Dec;37(12):2615-2629. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4667. Epub 2022 Nov 14. PMID: 36375809.

4. Khan AA, Guyatt G, Ali DA, et al. Management of Hypoparathyroidism. J Bone Miner Res. 2022 Dec;37(12):2663-2677. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4716. Epub 2022 Oct 31. PMID: 36161671.

5. Yao L, Li J, Li M, et al. Parathyroid Hormone Therapy for Managing Chronic Hypoparathyroidism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2022 Dec;37(12):2654-2662. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4676. Epub 2022 Nov 16. PMID: 36385517.

6. Khan AA, Bilezikian JP, Brandi ML, et al. Evaluation and Management of Hypoparathyroidism Summary Statement and Guidelines from the Second International Workshop. J Bone Miner Res. 2022 Dec;37(12):2568-2585. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4691. Epub 2022 Nov 14. PMID: 36054621.

Roman Jaeschke, MD, MSc: Good afternoon. Welcome to another edition of McMaster Perspective. We have a privilege of hosting Professor Aliya Khan, preeminent researcher in the area of parathyroid disease. The occasion is quite an unusual number of publications under her and her colleagues’ names, which happened in the preeminent Journal of [Bone and Mineral Research]. Professor Khan, could you tell us something about this initiative and what led to this number of publications about parathyroid problems?

Aliya Khan, MD: Yes, that’s really great. Thank you so much for asking me to join. It really is my pleasure to speak today. I wanted to just say that there was a need for an update on parathyroid disease, primary hyperparathyroidism as well as hypoparathyroidism, because we have new molecules coming out for treatment and we wanted to look at the evidence and then provide an update with our advanced knowledge about the biology and how these new molecules can help us to improve the well-being and overall function of our patients with parathyroid disease.

Roman Jaeschke: You mentioned “we.” Who do you mean?

Aliya Khan: “We” meaning parathyroid experts around the world. There are questions being asked, “Who should go for surgery?” Much like you were asking me, Roman. Who should go for surgery for hyperparathyroidism? How do we treat hypoparathyroidism? When should we use parathyroid hormone (PTH) therapy? When should we use conventional therapy?

Those are really key questions and we wanted to provide an evidence-based response. We felt that… at McMaster University—this is the home of evidence-based medicine—we spoke to Gordon Guyatt and we said, “Gordon, do you want to help us out?” We want to have a global consensus on these two conditions, hyperparathyroidism and hypoparathyroidism. What do we know today? How do we diagnose these conditions? How do we evaluate them? How do we treat them? What is the role of surgery? When do we use PTH versus conventional therapy? What are the complications?

Roman Jaeschke: Let’s tackle these questions one at a time. I was reading the papers with a considerable amount of pleasure. This is, since my medical school 40 years ago, probably the most difficult subject, and primary, secondary, and tertiary hyperparathyroidism, if it still exists, haunts me through years.

But let’s start with hypoparathyroidism because there is quite a number of articles about it. I understand that the majority of cases are actually related to the surgical complications or consequences, so my first question would be how to prevent them and how to stratify the risk, so to speak?

Aliya Khan: That’s a really great point that you’ve raised, and it’s important for us to remember that inadequate parathyroid function is most commonly seen post surgery, post neck surgery. It could be post parathyroidectomy, post thyroidectomy. Any extensive neck surgery that will impair the blood supply of the parathyroid glands or damage the parathyroid tissue can result in postsurgical hypoparathyroidism and 75% of people who have hypoparathyroidism have it post surgery. Now, the 25% that don’t have postsurgical hypoparathyroidism do require careful evaluation. Is it okay if I call you Roman instead of Professor Jaeschke?

Roman Jaeschke: Yes, absolutely.

Aliya Khan: So, Roman, the important point that I really wanted to emphasize to our colleagues is that we need to evaluate why a patient has hypoparathyroidism.

First, we make the diagnosis. If the calcium corrected for albumin or the ionized calcium is low and the PTH is low or inappropriately in the low to mid-normal reference range—because the normal response in the presence of hypocalcemia is an elevation in PTH—so, if the PTH is not elevated, then there’s a problem with inadequate parathyroid function. And if the patient hasn’t had neck surgery, then there’s a reason for it and we need to find out what the reason is.

So, 25% have nonsurgical hypoparathyroidism and the common causes are autoimmune disease, so it could be in isolation or a part of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 (APS-1). In this condition there can also be mucocutaneous candidiasis and adrenal insufficiency as well as a host of other minor features of APS-1.

There may be other reasons for hypoparathyroidism. Autoimmune is one of the common causes, then the genetic causes. Remember that we have genes that will result in the formation of normal parathyroid glands, and the function of the parathyroid glands is also determined by the genes. Also the destruction of parathyroid tissue can happen because of genetic mutations. Mutations in the genes that lead to the formation and the secretion of PTH or the destruction of parathyroid tissue, genetic mutations, can result in hypoparathyroidism.

Roman Jaeschke: So, on a practical level, if you see a person who has hypoparathyroidism and did not have neck surgery, what kind of evaluation do you use?

Aliya Khan: We do want everybody to think about these conditions. Is it autoimmune? Does our patient have adrenal insufficiency? Have they had mucocutaneous candidiasis? Do they have other features of genetic abnormalities such as a cleft palate, like DiGeorge syndrome? Do they have hearing impairment? Do they have kidney disease? Do they have heart disease? Because there are genetic abnormalities that result in syndromic causes of hypoparathyroidism.

In one of the papers—and there were about 18 papers that we published on hypo- and hyperparathyroidism—we carefully walk the practitioner through the evaluation of hypoparathyroidism. And then there are other causes of hypoparathyroidism, such as granulomatous disease or infiltration with iron, or copper, or aluminum. Metastatic disease can be a rare cause, as well as external radiation—that can be a cause. Magnesium abnormalities can actually cause hypoparathyroidism as well, both excess magnesium and inadequate magnesium, because magnesium binds to the calcium-sensing receptor and turns off PTH. So if you have too much magnesium, it’ll cause hypoparathyroidism.

Roman Jaeschke: I apologize for pushing a little bit more, but if you see this patient in your clinic, and your fellow reports that there is no obvious cause, you will say, “Please, dear fellow, order one, two, three, four, five.” I heard about the magnesium and maybe cortisol level. Is there anything you do routinely?

Aliya Khan: Yeah, that’s a really great question. I would check iron studies and make sure that copper and aluminum toxicity is not a possibility. Granulomatous disease, sarcoidosis—these are conditions that can also result in hypoparathyroidism. Look for the history and the physical features of genetic abnormalities. Hearing impairment, do they have hearing impairment? Do they have kidney disease? Have they had kidney stones? These are the features that we would be looking at.

Roman Jaeschke: All right. Now let’s move to treatment. Say you have nothing specific to do for the underlying disease and you are dealing with hypoparathyroidism. And I see, going through the papers, discussion about the use of parathyroid hormone replacement. Is it something new? Is it something difficult? Is it something expensive? Is it something better?

Aliya Khan: That’s a really good way of saying it, because it’s kind of all of those things. Up until now, the conventional therapy has consisted of… Well, if they don’t have enough PTH, that means that they’re not going to be able to reabsorb calcium through the kidneys. So there’s a leak through the kidneys. They’re not going to be able to access calcium from the skeleton and they’re not going to be able to convert 25-[hydroxyvitamin] D to 1,25-[dihydroxyvitamin] D. That will also impair calcium absorption from the bowel, so the calcium will be low.

What can we do? We can give them back calcium and we can give them active vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. But when we give them back more calcium and more 1,25 D, what happens is that the blood calcium goes up, so the kidney is seeing more calcium and it increases urine calcium because there’s no PTH to reabsorb that calcium and that causes more renal complications: more kidney stones, more nephrocalcinosis, and more kidney impairment.

So, yes, we can treat them with calcium and active vitamin D, but we will hasten the renal complications and that’s not good. That’s why giving back PTH would be ideal, because then we’ll be able to reabsorb that calcium through the kidney and we will be able to establish a normal serum calcium.

Roman Jaeschke: Okay. It sounds that at the physiological level there is no competition between those two. Do you mind telling me how expensive it is? It’s a lifelong therapy, I would think.

Aliya Khan: Now, this is where the wrinkles are and the devil is in the details. If we were to give PTH, we should give PTH so there’s 24-hour PTH availability and the molecule that we have, teriparatide (PTH 1-34), has a 1-hour half-life. There’s another molecule, PTH 1-84, which has a 3-hour half-life. Then there’s a third molecule, TransCon PTH, which has a 60-hour half-life. It’s like giving an infusion.

What we’ve seen looking at these 3 molecules is the effect is dependent on the half-life of the drug. If we give the short-acting PTH, we’re really not going to be able to demonstrate a big change in urine calcium and we’re not going to really be able to make a big difference unless we give it twice a day.

PTH 1-34, which is what’s available in Canada, is expensive. We’re looking at like CAD $500 a month for once-a-day dosing. So, twice-a-day dosing, that’s like CAD $1000. It’s expensive. We’re expecting that TransCon PTH will become available and it’s going to be approved—we’re expecting—by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2023 and we hopefully will have it available in Canada towards the end of 2023 or early part of 2024. That’s going to make a difference because we don’t have the 1-84, that was withdrawn in the United States because there were rubber particles in the solution. The only molecule that we do have in Canada is the 1-34 PTH, teriparatide.

Roman Jaeschke: Okay. Well, it looks like this is still an evolution. It repeatedly amazes me, the cost of new therapies. But to be honest, you’re not far away from new therapies for diabetes, or congestive heart failure, or some other, not mentioning some biologic immune treatments. Thank you for this.

I also know that you conducted a survey of practitioners dealing with hypoparathyroidism and you identified some areas of variability of practice. Could you tell us what we know and what we don’t know about how to treat hypoparathyroidism, or at least the majority of people?

Aliya Khan: Yeah, that’s a really great question, Roman. Basically when we did the systematic review to look to see how frequently people should be evaluated for hypoparathyroidism, we came up with 2 articles in the global literature, and so we thought, well, let’s see what practitioners around the world are doing.

We had 100 global experts on our task force and we surveyed them and asked them, “What do you do for your stable patient, for your unstable patient? How often do you evaluate them? Do you do a kidney ultrasound? Do you do brain imaging?” Because some of the complications of hypoparathyroidism are an elevation in phosphate, which then causes intracranial calcification and lens calcification in addition to kidney calcification.

We presented in the survey paper what the experts do, but there are certainly areas of disagreement. How often should we be evaluating these patients? Which tests should be done at baseline? But in general, we agree that everybody should have a renal ultrasound looking to see if there is already evidence of nephrocalcinosis or calcification of the renal parenchyma or if they already have renal stones, which may be present.

We didn’t come up with any clear-cut recommendation for brain imaging right now. But if patients do have cognitive decline or cognitive features or if they’ve had a seizure before—because patients with hypocalcemia can present with seizures—then we would definitely recommend brain imaging.

Roman Jaeschke: Professor Khan, you probably see a lot of people referred to you with a parathyroid condition. In terms of hypoparathyroidism, is there anything you would like to advise primary practitioners, which would make the flow of the patients easier? Something they could help you with in preparation of a patient for your consult?

Aliya Khan: Sure. Thank you. I think the important thing is to check the calcium and always make sure that we have an albumin because we want to get the corrected calcium for albumin or an ionized calcium.

It’s important to check PTH. It’s also important to check magnesium and phosphate and do a 24-hour urine for calcium and creatinine. Those are important points and we also always want to get renal function, assessment of renal function.

Then we can check the vitamin D assays because inadequate levels of vitamin D can result in hypocalcemia. In patients who have low levels of PTH we want to check the 25-hydroxyvitamin D and the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. If these basic tests can be done, Professor Jaeschke, that would be great.

Roman Jaeschke: Okay, thank you very much for this tour de force about hypoparathyroidism. I will invite you very soon to talk about hyperparathyroidism. Thank you very much for this very clear and useful explanation.

Aliya Khan: Thank you so much.

For part 2 of the interview, click here.

English

English

Español

Español

українська

українська