Aristeidis Katsanos, MD, PhD, vascular neurologist, assistant professor of medicine in the Faculty of Health Sciences at McMaster University, investigator at the Population Health Research Institute (PHRI), and fellow of the Canadian Stroke Consortium (CSC), meets with James Douketis, MD, expert in thromboembolism, to discuss the use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) following ischemic stroke.

For a Publications of the Week article discussing the use of DOACs in patients with AF after ischemic stroke, click here.

James Douketis, MD: Hello, everyone. My name is Jim Douketis and it’s my pleasure to welcome you to another edition of [McMaster Perspective]. I’m really delighted to be joined this week by Dr Aristeidis Katsanos, who is a stroke neurologist and an associate professor of medicine at McMaster University and who will provide his perspective on the ELAN (Early versus Late initiation of direct oral Anticoagulants in post-ischaemic stroke patients with atrial fibrillation) trial, which is a study looking at patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who suffered an ischemic stroke and looking at the timing of anticoagulation initiation. This is a topic that we’ve struggled with for decades.

Aristeidis, welcome, it’s a pleasure to have you as part of [McMaster Perspective].

Aristeidis Katsanos, MD, PhD: Thank you so much, Jim, for the kind invitation. I’m really excited and glad to discuss this paper.

As I said, it is a really important paper. It’s one of the questions that we get really commonly from our colleagues in internal medicine, also from you guys, the thrombosis team, when to start a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) in a patient with a recent stroke.

As you said really nicely, we didn’t have the evidence so far. We had evidence from observational studies and also we need to think that the trials that were done, they were regulatory trials for novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs). [Patients with] a recent stroke were excluded from participation in those trials. I think the ARISTOTLE (Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation) was the one that allowed stroke patients after 7 days to get into the trial, and the other [trials on] NOACs excluded [patients] with recent strokes.

James Douketis: Maybe you can give us a bit of a background, Aristeidis, about this concept of early initiation, more delayed initiation, and very delayed initiation as a function of the severity of stroke. I know that this was not studied per se in the ELAN trial, but clinicians have heard about the “1-3-6-12 day rule,” which refers to initiation of anticoagulation as a function of the severity of stroke. Can you talk a little bit about that, how it became the way it was, and perhaps about its relationship to this trial?

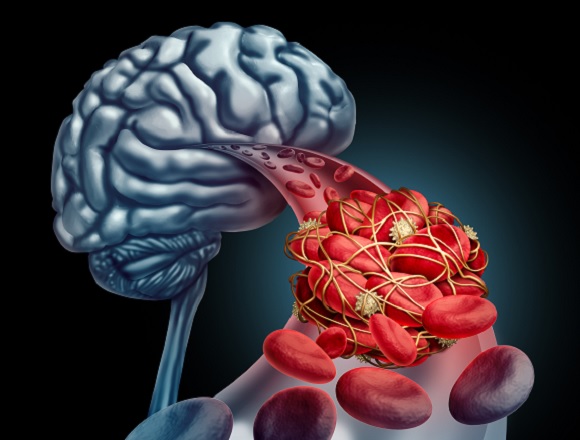

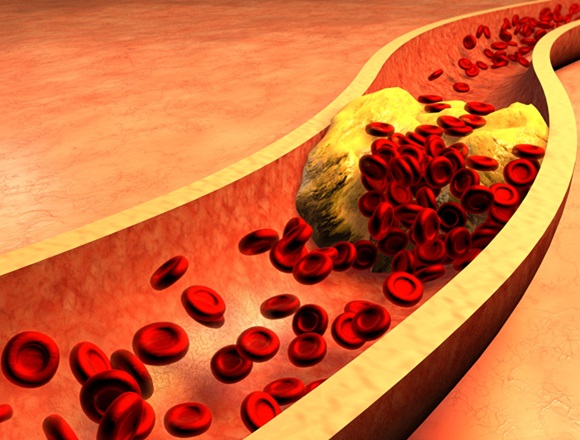

Aristeidis Katsanos: Yeah, for sure. When you consider restarting or starting a NOAC in a patient with recent stroke, what you are really balancing is the risk of bleeding to the risk of having a thromboembolic event. We know from observational studies—and that comes to no surprise—that the bigger the stroke is, the higher the risk of hemorrhagic transformation and bleeding to the brain. We have many studies in which they saw this.

The “1-3-6-12 day rule,” in fact, is an expert opinion. It was published in one of the papers from the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). What it says is that if you have a patient with a transient ischemic attack (TIA), you can start the NOAC the next day. If you have a patient with a minor stroke, you can start it on day 3; moderate stroke, day 6; and severe stroke, after day 12.

This rule takes into account the stroke severity based on a clinical scale. We have the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) where you assess the patient using some predefined criteria. This is a scale with scores from 0 to 42. The higher the score, the higher the severity.

What is the problem with the scale is that it’s very shifted towards the left hemisphere. If you have a left hemispheric infarction, you score higher on the NIHSS. The other thing is that in some stroke patients, there is a disparity between the severity of the stroke and the imaging. And I’ll give you 2 examples for that, just to understand better.

You may have a patient with a lacunar stroke, a very tiny, little stroke in the brain, which is <1.5 cm, and they score really high on the NIHSS, because the patient has dense hemiplegia on one side of the body. They score really high on the NIHSS, but the stroke size is small. Although you think that this is a severe stroke in terms of neuroimaging and also in terms of a risk of hemorrhagic transformation, the risk is low.

We have the same thing also with posterior cerebral artery (PCA) strokes—strokes in the posterior circulation where patients get only visual deficits. This case is the other way around: they score low on the NIHSS, they have only visual deficits, maybe some minor droopy face, but nothing really striking. But when you do a computed tomography (CAT) scan, you see a really sizable stroke. Although they score low based on clinical criteria, on the imaging you are very concerned that this patient may have hemorrhagic transformation and bleed into the brain. So you can see that there is a discrepancy between the clinical scaling and the neuroimaging scaling in terms of grading the risk of hemorrhagic transformation.

James Douketis: Well, thanks for that background. It’s something that we struggle with. It’s important to have interaction with the stroke neurologist to help delineate some of those nuances.

But let’s get back to the ELAN trial. By the way, I think they excluded patients with TIAs. They looked at people in the early initiation arm: it was within 48 hours if it was a mild to moderate stroke; 6 to 7 days if it was a more severe stroke; whereas in the control arm, it was, I believe, 3 days, and then 6 to 7 days, and then 12 to 14 days, depending on the severity.

What did you think of the results? Because it seemed to tell us that early initiation might be better. Is that what your impression was as well?

Aristeidis Katsanos: Yeah, the impression is that early initiation is at least noninferior. All of the authors, they didn’t run the trial as a noninferiority trial, so there was no prespecified hypothesis. By looking at the numbers, you can definitely make the conclusion that first, early start is safe, hemorrhagic transformation is very infrequent, so you can see that both groups, the early and the late, they had a risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage of 0.2%, which is our main fear, right? So the main fear of not starting early is the risk of bleeding and bleeding to the brain because you have a fresh stroke. So I think the first take-on point is that this risk is low.

Second, if you start early, it seems that it is at least noninferior in the 30-day outcome [inaudible] with the primary endpoint of the trial. If you take a peek at 90 days, you can see that there is a shift towards better outcomes and better prevention of stroke and thromboembolism if you start early.

Of course, we need to be careful because the 90-day endpoint was exploratory, so it wasn’t the primary endpoint of the trial. But what is my take-home [message] is that it’s safe and probably it’s even superior to start early rather than waiting. Just note that those patients were carefully selected—you see that they screened a lot of patients to get their 2000 participants and people with signs of parenchymal hemorrhage were excluded from the trial. So you have to be really careful in your imaging assessment and who are the patients in whom you are going to start early.

James Douketis: Okay. So, one other more practical question: is this a type of clinical scenario that the average internist can sort of handle? Or would you recommend that they run it by, discuss it with a neurologist or, if available, a stroke neurologist? How generalizable do you think these results are to, let’s say, a community practice setting?

Aristeidis Katsanos: I think they’re very generalizable. The only caveat to this trial is that you need to be able to interpret the imaging. You need to be able to see the size of the stroke, first of all; and second, to make sure that there is no parenchymal hematoma to the stroke.

I don’t believe that you have to be a stroke neurologist to be able to say those 2 items but at least you need to have some familiarity with neuroimaging. If you don’t feel confident, a call to a neurologist or a call to one of your radiology colleagues may be worthwhile to make sure that you know the size of the stroke and also the lack of parenchymal hematoma inside the infarct.

James Douketis: Dr Katsanos, thank you so much for your insights. This is an important trial. We’ve seen so many advances in the area of stroke neurology over the past decade or so, and this is just one more. It’s important because we are using the NOACs or DOACs more often. As you know, these are anticoagulants that have a very rapid, almost immediate onset and peak action occurring 1 to 3 hours after administration, so we have to use them cautiously in patients at risk for bleeding. I think this trial helps us to provide some guidance and some reassurance about their use in the setting of an acute ischemic stroke associated with AF.

Thank you again, Dr Katsanos, for your insights and your valuable time. We look forward to more studies in this area that is rapidly evolving.

Aristeidis Katsanos: Thanks so much, Dr Douketis, for the kind invitation and for the great discussion. We look forward to the implementation of this trial in the clinical setting and also the real-world experience from it. Thank you so much.

English

English

Español

Español

українська

українська