Internal Medicine Rapid Refreshers is a series of concise information-packed videos refreshing your knowledge on key medical issues that general practitioners may encounter in their daily practice. This episode explains the most important investigations and managements steps in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations.

Contents

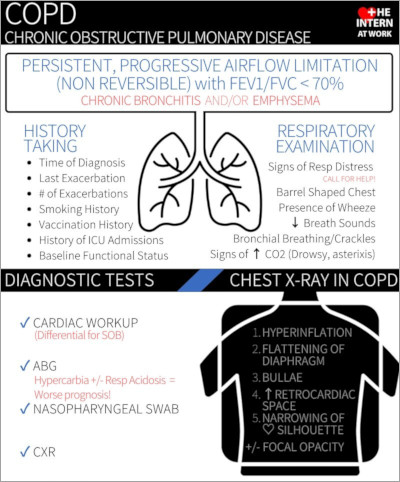

Infographic

Click to view the full image.

Infographic courtesy of The Intern at Work (theinternatwork.com).

Useful links

- Chapter on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) from the McMaster Textbook of Internal Medicine

Transcript

Introduction

I’m Siobhan Deshauer, a senior medical resident at McMaster University. In this video we will go through a practical approach to the diagnosis and management of a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation, sometimes abbreviated as COPDe. This Rapid Refresher is intended for subspecialty physicians who are returning to general internal medicine during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Always remember that you’re never alone managing these patients and there are physicians in the hospital and at home that you can call for additional assistance.

Pathophysiology

COPD exacerbations are characterized by acutely worsening respiratory symptoms that require additional therapy. Some common triggers include viral or bacterial infections, environmental exposure such as smoke or allergens, and medication nonadherence. Other diagnoses to consider with shortness of breath (SOB) include myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (CHF), a pneumothorax, or aspiration.

Investigations

Initial investigations are aimed at ruling out other diagnoses, identifying the trigger of the exacerbation, and determining the severity of the exacerbation.

Start with a basic panel of bloodwork (blood testing): complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, creatinine (Cr), troponin, and blood gas. Pay special attention to the rise in the CO2 level and if there is an acidosis present.

Get a chest x-ray, looking for signs of volume overload, an infiltrate, or a pneumothorax.

Perform electrocardiography (ECG) to look for signs of ischemia or arrhythmia.

Think about infections. Obtain nasopharyngeal swabs (NPSs) for viruses and sputum culture for bacteria. Consider blood cultures if you’re suspecting sepsis.

Consider computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA). Always keep the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism in the back of your mind. Look for clinical features, like active deep vein thrombosis (DVT), unexplained tachycardia, pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis, especially in patients with active cancer, recent surgery, or immobilization.

Acute management

There are 5 general principles of the acute management of a COPD exacerbation: supplemental oxygen, inhalers (“puffers”), steroids, antibiotics, and considering whether the patient requires ventilatory support.

1. Oxygen: Supplemental oxygen should be titrated to keep oxygen saturation between 88% and 92% in order to avoid worsening hypercapnia. This is especially important if the patient is known to have elevated CO2 at baseline.

2. Inhalers (“puffers”): Start with short-acting puffers: salbutamol (brand name Ventolin) and ipratropium bromide (brand name Atrovent). Both are dosed at 2 to 4 puffs every 4 hours, plus salbutamol 1 to 2 puffs every 1 hour as needed (prn). If the patient is already on long-acting bronchodilators, continue those on admission in addition to the short-acting ones.

3. Steroids: Steroids should be given by mouth (orally) rather than intravenously (IV) if the patient can take oral medications. A common example would be prednisone 40 mg daily for 5 days.

4. Antibiotics: Antibiotics should be considered for all patients, even those without a consolidation on their x-ray, if they meet 2 out of these 3 criteria: shortness of breath, sputum purulence, and increased sputum quantity. What antibiotics should be used? You can choose a respiratory fluoroquinolone, like levofloxacin or moxifloxacin. Another good option is a combination of a beta-lactam and a beta-lactamase inhibitor, like amoxicillin/clavulanate (clavulanic acid). If the patient looks quite ill—if they look to be septic or have a clear pneumonia—then consider using a beta-lactam plus a macrolide, such as ceftriaxone and azithromycin.

5. Ventilation: Who would benefit from noninvasive ventilation, like bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP)? Patients who have severe dyspnea with increased work of breathing whose blood gases show a pH <7.35 with CO2 >45 mm Hg. But caution is required: If there is a high suspicion for COVID-19, we do not recommend using BiPAP because the blowing air can spread and aerosolize the virus. If you’re evaluating if your patient is going to benefit from BiPAP, have a discussion with the respiratory therapist and the intensive care unit (ICU) attending physician on call and make that decision together, weighing up the risks and benefits. If you are using BiPAP, remember the contraindications: decreased level of consciousness (LOC), inability to clear secretions, facial trauma, respiratory arrest, and significant hemodynamic instability. If the patient does not qualify for BiPAP or if BiPAP fails, then call the intensive care unit (ICU) and consider the need for intubation.

In summary, when treating a patient with a COPD exacerbation, consider oxygen, puffers, steroids, antibiotics, and whether the patient needs ventilation.

Credits

For more information about COPD and COPD exacerbations, take a look at the resources linked here, including the chapter on COPD from the McMaster Textbook of Internal Medicine and an infographic from The Intern at Work.

I would like to thank those who collaborated on this project, including intensivist Doctor Roman Jaeschke (Divisions of Critical Care and Internal Medicine; editor for this video) and respirologist Doctor Joshua Wald (Division of Respirology; consultant for this video).

English

English

Español

Español

українська

українська